Easter Rising

| Easter Rising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the movement for Irish independence | |||||||

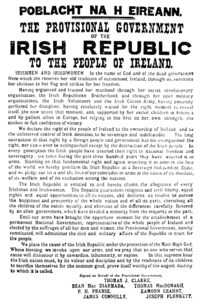

Proclamation of the Republic, Easter 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

File:RIC Station Badge.gif Royal Irish Constabulary | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Patrick Pearse, James Connolly |

Brigadier-General Lowe General Sir John Maxwell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1250 in Dublin, c. 2-3000 elsewhere, but they took little or no part in fighting | 16,000 troops and 1000 armed police in Dublin by end of the week | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 64 killed, 16 executed | 157 killed, 318 wounded | ||||||

| 220 civilians killed, 600 wounded | |||||||

The Easter Rising (Irish: Éirí Amach na Cásca) was a rebellion staged in Ireland in Easter Week, 1916.

The rising was an attempt by militant Irish republicans to win independence from Britain by force of arms. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798. The Rising, which was largely organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, lasted from Easter Monday April 24 to April 30, 1916. Members of the Irish Volunteers, led by school teacher and barrister Patrick Pearse, joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly, seized key locations in Dublin and proclaimed an Irish Republic independent of Britain. The Rising was suppressed after six days of fighting, and its leaders were court-martialled and executed. Despite its military failure, it can be judged as being a significant stepping-stone in the eventual creation of the Irish Republic.

Background: Parliamentary politics v. physical force

The event is seen as a key turning-point on the road to Irish independence, as it marked a split between physical force Irish republicanism and mainstream non-violent nationalism represented by the Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond. Redmond, through democratic parliamentary politics, had won an initial stage of Irish self-government within the United Kingdom, granted through the Third Home Rule Act 1914. This Act, limited by the fact that it partitioned Ireland into Northern Ireland and "Southern Ireland", was placed on the statute books in September 1914, but suspended for the duration of World War I (it ultimately was enacted under the Government of Ireland Act, 1920). By the end of the war, however, and largely as a result of the Rising, the support of nationalist voters had swung away from the IPP to the militant republicans, as represented by the Sinn Féin Party.

Planning the Rising

Template:IrishR While the Easter Rising was for the most part carried out by the Irish Volunteers, it was planned by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Shortly after the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the Supreme Council of the IRB met and, under the old dictum that "England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity", decided to take action sometime before the conclusion of the war. To this end, the IRB's treasurer, Tom Clarke formed a Military Council to plan the rising, initially consisting of Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett, with himself and Seán Mac Diarmada added shortly thereafter. All of these were members of both the IRB, and (with the exception of Clarke) the Irish Volunteers. Since its inception in 1913, they had gradually commandeered the Volunteers, and had fellow IRB members elevated to officer rank whenever possible; hence by 1916 a large proportion of the Volunteer leadership were devoted republicans in favor of physical force. A notable exception was the founder and Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill, who planned to use the Volunteers as a bargaining tool with Britain following World War I, and was opposed to any rebellion that stood little chance of success. MacNeill approved of a rebellion only if the British attempted to impose conscription on Ireland for the World War or if they launched a campaign of repression against Irish nationalist movements. In such a case he believed that an armed rebellion would have mass support and a reasonable chance of success. MacNeill's view was supported even by some within the IRB, including Bulmer Hobson. Nevertheless, the advocates of physical force within the IRB hoped either to win him over to their side (through deceit if necessary) or bypass his command altogether. They were ultimately unsuccessful with either plan.

The plan encountered its first major hurdle when James Connolly, head of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a group of armed socialist trade union men and women, completely unaware of the IRB's plans, threatened to initiate a rebellion on their own if other parties refused to act. As the ICA was barely 200 strong, any action they might take would result in a fiasco, and spoil the chance of a potentially successful rising by the Volunteers. Thus the IRB leaders met with Connolly in January 1916 and convinced him to join forces with them. They agreed to act together the following Easter, and made Connolly the sixth member of the Military Committee (Thomas MacDonagh would later become the seventh and final member).

In an effort to thwart informers, and, indeed, the Volunteers' own leadership, early in April Pearse issued orders for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" by the Volunteers for Easter Sunday (which he had the authority to do, as Director of Organization). The idea was that the true republicans within the organization (particularly IRB members) would know exactly what this meant, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities in Dublin Castle would take it at face value. However, MacNeill got wind of what was afoot and threatened to "do everything possible short of phoning Dublin Castle" to prevent the rising. Although he was briefly convinced to go along with some sort of action when Mac Diarmada revealed to him that a shipment of German arms was about to land in County Kerry, planned by the IRB in conjunction with Sir Roger Casement (who ironically had just landed in Ireland in an effort to stop the rising), the following day MacNeill reverted to his original position when he found out that the ship carrying the arms had been scuttled. With the support of other leaders of like mind, notably Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly, he issued a countermand to all Volunteers, cancelling all actions for Sunday. This only succeeded in putting the rising off for a day, although it greatly reduced the number of men who turned out.

The Rising

The outbreak of the Rising

The original plan, largely devised by Plunkett (and apparently very similar to a plan worked out independently by Connolly), was to seize strategic buildings throughout Dublin in order to cordon off the city, and resist the inevitable counter-attack by the British army. If successful, the plan would have left the rebels holding a compact area of central Dublin, roughly bounded by the canals and the circular roads. However, this strategy would have required more men than the 1,250 or so who were actually mobilized on Easter Monday. As a result, the rebels left several key points within the city, notably Dublin Castle and Trinity College, in British hands, meaning that their own forces were separated from each other. This in effect doomed the rebel positions to be isolated and taken one after the other. In the west of the country, local units were intended to try to hold the west bank of the river Shannon for as long as possible. However, without adequate numbers, arms or military expertise on the Volunteers' part, this was never a realistic prospect. Overall, the insurgents' hope was that the British would concede Irish self-government rather than divert resources from the Western Front to try to contain a rebellion in their rear.

The Volunteers' Dublin division had been organized into 4 battalions, each under a commandant who the IRB made sure were loyal to them. A makeshift 5th battalion was put together from parts of the others, and with the aid of the ICA. This was the battalion of the headquarters at the General Post Office, and included the President and Commander-in-Chief, Pearse, the commander of the Dublin division, Connolly, as well as Clarke, Mac Diarmada, Plunkett, and a then-obscure young captain named Michael Collins. Connolly asked Eamon Bulfin to hoist two flags up on the flag poles on either end of the GPO roof. The tricolour was hoisted at the right corner of Henry Street while a green flag with the inscription 'Irish Republic' was hoisted at the left corner at Princess Street. Having taken over the Post Office, Pearse read the Proclamation of the Republic to a largely indifferent crowd outside the GPO.

A small team of volunteers attacked the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park in an effort to obtain weapons and create a large explosion to signal the start of the rising. Meanwhile the 1st battalion under Commandant Ned Daly seized the Four Courts and areas to the northwest; the 2nd battalion under Thomas MacDonagh established itself at Jacob's Biscuit Factory, south of the city center; in the east Commandant Éamon de Valera commanded the 3rd battalion at Boland's Bakery; and Ceannt's 4th battalion took the workhouse known as the South Dublin Union to the southwest. Members of the ICA under Michael Mallin and Constance Markievicz also commandeered St. Stephen's Green. An ICA unit under Seán Connolly made a half-hearted attack on Dublin Castle, not knowing that it was defended by only a handful of troops. After shooting dead a police sentry and taking several casualties themselves from sniper fire, the group occupied the adjacent Dublin City Hall. Seán Connolly was the first rebel casualty of the week, being killed outside Dublin Castle. Other volunteers also occupied 25 Northhumberland Road and Carisbrook House.

The breakdown of law and order that accompanied the rebellion was marked by widespread looting, as Dublin's slum population ransacked the city's shops. Ideological tensions came to the fore when a Volunteer officer gave an order to shoot looters, only to be angrily countermanded by James Connolly.

As Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order prevented nearly all areas outside of Dublin from rising, the command of the great majority of active rebels fell under Connolly, who some say had the best tactical mind of the group. After being badly wounded, Connolly was still able to command by having himself moved around on a bed. (Although he had optimistically insisted that a capitalist government would never use artillery against their own property, it took the British less than 48 hours to prove him wrong.) The British commander, Brigadier-General Lowe, worked slowly, unsure of how many he was up against, and with only 1,200 troops in the city at the outset. Lowe declared martial law and the British forces put their efforts into securing the approaches to Dublin Castle and isolating the rebel headquarters at the GPO. Their main firepower was provided by the gunboat Helga and field artillery summoned from their garrison at Athlone which they positioned on the northside of the city at Prussia Street, Phibsborough and the Cabra road. These guns shelled large parts of the city throughout the week and burned much of it down. (The first building shelled was Liberty Hall, which ironically had been abandoned since the beginning of the Rising.) So inaccurate was much of the fire that British units, believing that they were being shelled by rebel guns--of which the insurgents had none--returned fire against their own artillery. Interestingly the Helga's guns had to stop firing as the elevation necessary to fire over the railway bridge meant that her shells were endangering the Viceregal Lodge in Phoenix Park, (Helga was later bought by the Government of the Irish Free State, and was the first ship in its Navy [1]).

British reinforcements arrive

Reinforcements were rushed to Dublin from England, along with a new commander, General John Maxwell. Outnumbering the rebels with approximately 16,000 British troops and 1,000 armed Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) (the IRB/Volunteers are estimated at about 1,000 and the ICA at under 250), they bypassed many of the defences and isolated others to the extent that by the end of the week the only order they were able to receive was the order to surrender. The headquarters itself saw little real action. The heaviest fighting occurred at the rebel-held positions around the Grand Canal, which the British seemed to think they had to take to bring up troops who had landed in Dún Laoghaire port. The rebels held only a few of the bridges across the canal and the British might have availed themselves of any of the others and isolated the positions. Due to this failure of intelligence, the Sherwood Foresters regiment were repeatedly caught in a cross-fire trying to cross the canal at Mount Street. Here a mere twelve volunteers were able to severely disrupt the British advance, killing or wounding 240 men. The rebel position at the South Dublin Union (site of the present day St James' Hospital), further west along the canal, also inflicted heavy losses on British troops trying to advance towards Dublin Castle. Cathal Brugha, a rebel officer, distinguished himself in this action and was badly wounded. Shell fire and shortage of ammunition eventually forced the rebels to abandon these positions before the end of the week. The rebel position at St Stephen's Green, held by the Citizen Army under Michael Mallin, was made untenable after the British placed snipers and machine guns in the surrounding buildings. As a result, Mallin's men retreated to the Royal College of Surgeons building, where they held out until they received orders to surrender.

Many of the insurgents, who could have been deployed along the canals or elsewhere where British troops were vulnerable to ambush, were instead ensconced in large buildings such as the GPO, the Four Courts and Boland's Mill, where they could achieve little. The rebel garrison at the GPO barricaded themselves within the post office and were soon shelled from afar, unable to return effective fire, until they were forced to abandon their headquarters when their position became untenable. The GPO garrison then hacked through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in Moore Street. On Saturday April 29 from this new headquarters, after realizing that all that could be achieved was further loss of life, Pearse issued an order for all companies to surrender.

The Rising outside Dublin

Irish Volunteer units turned out for the Rising in several places outside of Dublin, but due to Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order, most of them returned home without fighting. In addition, due to the interception of the German arms aboard the "Aud", the provincial Volunteer units were very poorly armed.

In the north, several Volunteer companies were mobilised in County Tyrone and 132 men on the Falls Road in Belfast.

In the west Liam Mellows led 600-700 Volunteers in abortive attacks on several Police stations, at Oranmore and Clarinbridge in County Galway. There was also a skirmish at Carnmore in which two RIC men were killed. However his men were very badly armed, with only 25 rifles and 300 shotguns, many of them being equipped only with pikes. Towards the end of the week, Mellows' followers were increasingly poorly-fed and heard that large British reinforcements were being sent westwards. In addition, the British warship, the HMS Gloucester arrived in Galway Bay and shelled the fields around Athenry where the rebels were based. On April 29, the Volunteers, judging the situation to be hopeless, dispersed from the town of Athenry. Many of these Volunteers were arrested in the period following the rising, while others, including Mellows had to go "on the run" to escape. By the time British reinforcements arrived in the west, the rising there had already disintegrated.

In the east, Seán MacEntee and County Louth Volunteers killed a policeman and a prison guard. In county Wexford, the Volunteers took over Enniscorthy from Tuesday until Friday, before symbolically surrendering to the British Army at Vinegar Hill – site of a famous battle during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

Around 1,000 Volunteers mustered in Cork, under Thomas MacCurtain on Easter Sunday, but they dispersed after receiving several contradictory orders from the Volunteer leadership in Dublin. Only at Ashbourne, County Meath was there real fighting. There, the North County Dublin Volunteers under Thomas Ashe ambushed an RIC police patrol, killing 8 and wounding 15, in an action that pre-figured the guerrilla tactics of the Irish Republican Army in the Irish War of Independence 1919-1921.

Casualties

The total casualties for the week's fighting came to over 1,200. Sixty-four rebel volunteers were killed and 16 more were executed after the Rising. The British Army suffered 140 killed and 318 wounded. The police (RIC and Dublin Metropolitan Police) suffered 17 deaths. At least 220 civilians were killed and 600 wounded. There may have been further civilian casualties which were never reported to the authorities. The only leader of the rising to die in the course of the hostilities themselves was The O'Rahilly, who died after being hit by small arms fire while escaping from the burning GPO.

Some 3,430 suspects were arrested; 90 sentenced to death; and 16 leaders (including all seven signatories of the independence proclamation) actually executed (May 3–12). Among them was the seriously-wounded Connolly, shot while tied to a chair because he was too weak to stand. A total of 1,480 people were interned after the Rising, many of whom, like Arthur Griffith, had little or nothing to do with the affair.

Reactions to the Rising

The rebels had little public support at the time, and were largely blamed for hundreds of people being killed and wounded, (including many civilians caught in the crossfire). At the time the executions were demanded in motions passed in some Irish local authorities and by many newspapers, including the Irish Independent and The Irish Times.[2] Prisoners being transported to Frongoch internment camp in Wales were jeered and spat upon by angry Dubliners, many of whom had relatives serving with British forces in the First World War. The rebels' Proclamation had referred to their "gallant allies in Europe", generally known as the Central Powers; they considered proclaiming the Kaiser's son Joachim as king if their allies won the war.[3][4]

The reaction of some Irish people was more favourable to the Rising. Ernie O'Malley for instance, a young medical student, despite having had no previous involvement with nationalist politics, spontaneously joined in the fighting and fired on British troops. Moreover, Irish nationalist opinion was appalled by the executions and wholesale arrests of political activists (most of whom had no connection with the rebellion) that took place after the Rising. This indignation led to a radical shift in public perception of the Rising and within three years of its failure, the separatist Sinn Féin party won an overwhelming majority in a general election, supporting the creation of an Irish Republic and endorsing the actions of the 1916 rebels.

Recruitment for the British Army among Irish Catholics fell after the Rising.

Perhaps the most significant literary reaction to the uprising was issued publicly by Ireland’s most acclaimed poet, W.B. Yeats, in one of his most celebrated poems: Easter, 1916.

Infiltrating Sinn Féin

The executions marked the beginning of a change in Irish opinion, much of which had until now seen the rebels as irresponsible adventurists whose actions were likely to harm the nationalist cause. As freed detainees reorganised the Republican forces, nationalist sentiment slowly began to swing behind the hitherto small advanced nationalist Sinn Féin party, ironically not itself involved in the uprising, but which the British government and Irish media wrongly blamed for being behind the Rising. The surviving Rising leaders, under Eamon de Valera, infiltrated Sinn Féin and superseded its previous leadership under Arthur Griffith, who had founded the party in 1905 to campaign for an Anglo-Irish Dual monarchy on the Austro-Hungarian model. Sinn Féin and the Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond fought a series of inconclusive political battles, with each winning by-elections, until the Conscription Crisis of 1918 (when Britain tried to force conscription on Ireland) swung public opinion decisively behind Sinn Féin.

"What if the British had been lenient to the Irish rebel leaders?" is a question that still lends itself to lively debate.[5]

1918 General Election

The general elections to the British Parliament in December 1918 resulted in a Sinn Féin landslide in Ireland (many seats were uncontested), whose MPs gathered in Dublin to proclaim the Irish Republic (January 21, 1919) under the President of Dáil Éireann, Eamon de Valera, who had escaped execution in 1916 through luck. (His physical location away from the other prisoners prevented his immediate execution, while his American citizenship led to a delay while the legal situation was clarified. By the time a decision was taken to execute him, and his name had risen to the top of the executions list, all executions had been halted.)

Surviving officers of the rising (including de Valera, Cathal Brugha, and Michael Collins) went on to organise the Irish War of Independence from 1919-1921 which resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and independence for 26 of Ireland's 32 counties. The executed leaders of the Easter Rising are venerated in the Irish Republican tradition as martyrs and as founders of the Irish Republic.

Legacy of the Rising

Critics of the Rising such as Kevin Myers have pointed to the fact that the Rising is generally seen as having been doomed to military defeat from the outset, and to have been understood as such by at least some of its leaders. Such critics have therefore seen in it elements of a "blood sacrifice" in line with some of the romantically-inclined Pearse's writings. Though the violent precursor to Irish statehood, it did nothing to reassure Irish unionists nor alleviate the demand to partition Ulster. Others, however, point out that the Rising had not originally been planned with failure in mind, and that the outcome in military terms might have been very different if the weapons from the "Aud" had arrived safely and if MacNeill's countermanding order had not been issued. Supporters also contend that Ireland had been left with no other way of attaining independence other than an armed rebellion.

Most historians would agree that the decision to shoot the survivors backfired on the British Authorities. However, given the circumstances of the time and the nature of the offences it is difficult to see that there was any other appropriate punishment. Britain was fighting a war on an unprecedented scale, a war in which many thousands of Irish volunteers had already lost their lives. Armed rebellion, in time of war, in league with the enemy was always going to attract the most severe penalties.

Nationalist views of the Rising have stressed the role of the Rising in stimulating latent sentiment towards Irish independence. On this view the momentous events of 1918-22 are directly attributable to the revitalisation of the nationalist consciousness as a result of the Rising and its immediate aftermath.

The theory has also been mooted that the Rising should have given the Irish Republic a role in a peace conference following an anticipated German victory in the First World War, which of course did not happen.

Historians generally date Irish independence (for the 26 counties) from 1 April 1922 (transfer of executive power under the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed between Irish delegates and the British government after the Anglo-Irish War, forming the Irish Free State) and 6 December 1922 (transfer of legislative power) rather than from the 1916 Rising. The Irish Free State existed until 1937 when Bunreacht na hÉireann (the Irish constitution) was introduced, renaming the country "Ireland". At this stage Ireland was a Republic in everything but name. In 1949 the Oireachtas officially declared Ireland to be a Republic.

Socialism and the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising has sometimes been described as the first socialist revolution in Europe. Whether or not such a statement is true is debatable. Of the leaders, only James Connolly was devoted to the socialist cause (he was a former official of the American IWW and General Secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union at the time of his execution). Although the others nominally accepted the notion of a socialist state in order to convince Connolly to join them, their dedication to this concept is highly questionable at best. Political and cultural revolutions were much more important in their minds than economic revolution. Connolly clearly was skeptical of his colleagues' sincerity on the subject, and was prepared for an ensuing class struggle following the establishment of a republic. Furthermore, Eamon de Valera, the prominent surviving leader of the rising and a dominant figure in Irish politics for nearly half a century, could hardly be described as Socialist. Four years later, the Soviet Union would be the first and only country to recognise the Irish Republic, later abolished under the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Lenin, who was an admirer of Connolly, rounded on communists who had derided the Easter Rising for involving bourgeois elements. He contended that communists would have to unite with other disaffected elements of society to overthrow the existing order, a point he went on to prove the following year during the Russian Revolution.

Men executed for their role in the Easter Rising

- Patrick Pearse (1879-May 3, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Thomas J. Clarke (1858-May 3, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Thomas MacDonagh (1878-May 3, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Joseph Mary Plunkett (1887-May 4, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Edward (Ned) Daly (1891-May 4, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- William Pearse (1881-May 4, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Michael O'Hanrahan (1877-May 4, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- John MacBride (1865-May 5, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Éamonn Ceannt (1881-May 8, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Michael Mallin(1874-May 8, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Cornelius Colbert (1888-May 8, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Seán Heuston (1891-May 8, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Seán Mac Diarmada (1884-May 12, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- James Connolly (1868-May 12, 1916, shot, Kilmainham)

- Thomas Kent (1865-May 9. 1916, shot, Cork)

- Roger Casement (1864-August 4, 1916, hanged, London)

Notes

- ^ Irish Times article - 1916 - "Helga's roles after Rising"

- ^ 1916 Easter Rising - Newspaper archive — from the BBC History website

- ^ referred to on page 324 in 'Daisy, Princess of Pless' ed. Desmond Chapman-Huston, Murray, London 1928, ASIN: B00086RUJU

- ^ Desmond FitzGerald, Memoirs 1913 to easter 1916 (Liberties Press, Dublin 2006) p.143. ISBN 1-905483-05-8

- ^ There was a Boer uprising in South Africa at the start of World War I when Afrikaners who wished to break the link between South Africa and the British Empire, allied themselves with the Germans of German South West Africa. The revolt was crushed by forces loyal to the South African Government. In contrast to the British reaction to the Easter Rising, in a gesture of reconciliation the South African government was lenient on those rebel leaders who survived the rebellion and encouraged them to work for change within the constitution. This strategy worked and there were no further armed rebellions by Afrikaners who opposed links with Britain. In 1921 Jan Smuts a leading South African statesman and soldier was able to bring this example to the notice of the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and it helped to persuade the British Government to compromise when negotiating the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Bibliography

- Max Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, Dublin 1916 ISBN 1-57098-042-X

- Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: The Easter Rising ISBN 0-304-35902-5

- Michael Foy and Brian Barton, The Easter Rising ISBN 0-7509-2616-3

- C Desmond Greaves The Life and Times of James Connolly

- Robert Kee, The Green Flag ISBN 0-14-029165-2

- F.X. Martin (ed.), Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising, Dublin 1916

- Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic

- F.S.L. Lyons, Ireland Since the Famine ISBN 0-00-633200-5

- John A. Murphy, Ireland In the Twentieth Century

- Edward Purdon, The 1916 Rising

- Charles Townshend, Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion

- The Memoirs of John M. Regan, a Catholic Officer in the RIC and RUC, 1909–48, Joost Augusteijn, editor, Witnessed Rising, ISBN: 978-1-84682-069-4.

- Conor Kostick & Lorcan Collins, The Easter Rising, A Guide to Dublin in 1916 ISBN-10 0-86278-638-X