Jellyfish: Difference between revisions

Epipelagic (talk | contribs) m →Jellyfish blooms: is cited |

→Body systems: Replaced hyphens (-) with em-dashes (—). See WP:dash |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==Body systems== |

==Body systems== |

||

Jellyfish do not have specialized [[Gastrointestinal tract|digestive]], [[Osmoregulation|osmoregulatory]], [[Central nervous system|central nervous]], [[Respiratory system|respiratory]], or [[Circulatory system|circulatory]] systems. They digest using the [[gastrodermis|gastrodermal]] lining of the [[gastrovascular cavity]], where nutrients are absorbed. They do not need a respiratory system since their skin is thin enough that the body is oxygenated by [[diffusion]]. They have limited control over movement, but can use their [[hydrostatic skeleton]] to accomplish movement through contraction-pulsations of the bell-like body; some species actively swim most of the time, while others are passive much of the time.{{Fact|date=July 2009}} Jellyfish are composed of more than 90% water; most of their umbrella mass is a gelatinous material |

Jellyfish do not have specialized [[Gastrointestinal tract|digestive]], [[Osmoregulation|osmoregulatory]], [[Central nervous system|central nervous]], [[Respiratory system|respiratory]], or [[Circulatory system|circulatory]] systems. They digest using the [[gastrodermis|gastrodermal]] lining of the [[gastrovascular cavity]], where nutrients are absorbed. They do not need a respiratory system since their skin is thin enough that the body is oxygenated by [[diffusion]]. They have limited control over movement, but can use their [[hydrostatic skeleton]] to accomplish movement through contraction-pulsations of the bell-like body; some species actively swim most of the time, while others are passive much of the time.{{Fact|date=July 2009}} Jellyfish are composed of more than 90% water; most of their umbrella mass is a gelatinous material — the jelly — called [[mesoglea]] which is surrounded by two layers of epithelial cells which form the umbrella (top surface) and subumbrella (bottom surface) of the bell, or body. |

||

Jellyfish do not have a brain or central [[nervous system]], but rather have a loose network of nerves, located in the [[Squamous epithelium|epidermis]], which is called a "[[nerve net]]." A jellyfish detects various stimuli including the touch of other animals via this nerve net, which then transmits impulses both throughout the nerve net and around a circular nerve ring, through the [[rhopalial lappet]], located at the rim of the jellyfish body, to other nerve cells. Some jellyfish also have [[ocellus|ocelli]]: light-sensitive organs that do not form images but which can detect light, and are used to determine up from down, responding to sunlight shining on the water's surface. |

Jellyfish do not have a brain or central [[nervous system]], but rather have a loose network of nerves, located in the [[Squamous epithelium|epidermis]], which is called a "[[nerve net]]." A jellyfish detects various stimuli including the touch of other animals via this nerve net, which then transmits impulses both throughout the nerve net and around a circular nerve ring, through the [[rhopalial lappet]], located at the rim of the jellyfish body, to other nerve cells. Some jellyfish also have [[ocellus|ocelli]]: light-sensitive organs that do not form images but which can detect light, and are used to determine up from down, responding to sunlight shining on the water's surface. |

||

Revision as of 03:17, 29 July 2009

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (May 2009) |

| Jellyfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pacific sea nettle, Chrysaora fuscescens, endemic to the west coast of North America. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Scyphozoa Goette, 1887

|

| Orders | |

Jellyfish (also known as jellies or sea jellies) are free-swimming members of the phylum Cnidaria. They have several different morphologies that represent several different cnidarian classes including the Scyphozoa (over 200 species), Staurozoa (about 50 species), Cubozoa (about 20 species), and Hydrozoa (about 1000-1500 species that make jellyfish and many more that do not)[1][2]. The jellyfish in these groups are also called, respectively, scyphomedusae, stauromedusae, cubomedusae, and hydromedusae; medusa is another word for jellyfish. (Medusa is also the word for jellyfish in Modern Greek, Finnish, Portuguese, Romanian, Hebrew, Serbian, Croatian, Spanish, Italian, Hungarian, Polish, Lithuanian, Czech, Slovak, Russian, Bulgarian and Catalan). [citation needed]

Jellyfish are found in every ocean, from the surface to the deep sea.[citation needed] Some hydrozoan jellyfish, or hydromedusae, are also found in fresh water and are less than half an inch in size. They are partially white and clear and do not sting. This article focuses on scyphomedusae. These are the large, often colorful, jellyfish that are common in coastal zones worldwide.

In its broadest sense, the term jellyfish also generally refers to members of the phylum Ctenophora. Although not closely related to cnidarian jellyfish, ctenophores are also free-swimming planktonic carnivores, are generally transparent or translucent, and exist in shallow to deep portions of all the world's oceans.

Etymology and taxonomic history

Since jellyfish are not actually fish, some people consider the term jellyfish a misnomer, and American public aquariums have popularized use of the terms jellies or sea jellies instead.[citation needed] Others find the word jellyfish to be equally useful and picturesque, and prefer it over jellies. The word jellyfish is used to denote several different kinds of cnidarians, all of which have a basic body structure that resembles an umbrella, including scyphozoans, staurozoans (stalked jellyfish), hydrozoans, and cubozoans (box jellyfish). Some textbooks[which?] refer to scyphozoans as "true jellyfish," but this term is really quite meaningless[citation needed] and should be dropped from modern usage - none of these jellyfish are more true than any of the others.

In its broadest usage, some scientists[which?] occasionally include members of the phylum Ctenophora (comb jellies) when they are referring to jellyfish. Other scientists[which?] prefer to use the more all-encompassing term "gelatinous zooplankton", when referring to these, together with other soft-bodied animals in the water column.

The class name Scyphozoa comes from the Greek word skyphos (σκύφος), denoting a kind of drinking cup and alluding to the cup shape of the organism.

A group of jellyfish is sometimes called a bloom or a swarm.[citation needed] Using "bloom" implies that larger numbers than usual are present.[citation needed] Using "swarm" implies some kind of active ability to stay together, which a few species like Aurelia, the moon jelly, demonstrate.[citation needed]

Many jellyfish have a second part of their life cycle, which is called the polyp phase. When single polyps, arising from a single egg, develop into a multiple-polyp cluster, connected to each other by strands of tissue called stolons, they are said to be "colonial." A few polyps never proliferate and are referred to as "solitary" species.[citation needed]

Body systems

Jellyfish do not have specialized digestive, osmoregulatory, central nervous, respiratory, or circulatory systems. They digest using the gastrodermal lining of the gastrovascular cavity, where nutrients are absorbed. They do not need a respiratory system since their skin is thin enough that the body is oxygenated by diffusion. They have limited control over movement, but can use their hydrostatic skeleton to accomplish movement through contraction-pulsations of the bell-like body; some species actively swim most of the time, while others are passive much of the time.[citation needed] Jellyfish are composed of more than 90% water; most of their umbrella mass is a gelatinous material — the jelly — called mesoglea which is surrounded by two layers of epithelial cells which form the umbrella (top surface) and subumbrella (bottom surface) of the bell, or body.

Jellyfish do not have a brain or central nervous system, but rather have a loose network of nerves, located in the epidermis, which is called a "nerve net." A jellyfish detects various stimuli including the touch of other animals via this nerve net, which then transmits impulses both throughout the nerve net and around a circular nerve ring, through the rhopalial lappet, located at the rim of the jellyfish body, to other nerve cells. Some jellyfish also have ocelli: light-sensitive organs that do not form images but which can detect light, and are used to determine up from down, responding to sunlight shining on the water's surface.

Jellyfish blooms

The presence of blooms in the ocean is usually seasonal, responding to the availability of prey, increasing with temperature and sunshine. Ocean currents tend to congregate jellyfish into large swarms or "blooms", consisting of hundreds or thousands of individuals. In addition to sometimes being concentrated by ocean currents, blooms can furthermore be the result of unusually high populations in some years. The formation of these blooms is a complex process that depends on ocean currents, nutrients, temperature and ambient oxygen concentrations.[citation needed] Jellyfish are most likely to stay in blooms that are quite large and can reach up to 100,000 in each.

There is very little data about changes in global jellyfish populations over time, besides "impressions" in the public memory. In most places in the world, scientists have no quantitative data about what jellyfish populations used to be like, or quantitative data about what is happening in the present[3]. Recent speculation about increases in jellyfish populations have been based on no "before" data.

According to Claudia Mills of the University of Washington, increasing frequency of jellyfish blooms globally might be attributed to humans' impact on marine systems. She says that in some locations jellyfish may be filling ecological niches formerly occupied by overfished creatures, but notes that we lack data to show that is indeed true[3]. Jellyfish researcher Marsh Youngbluth further clarifies that "jellyfish feed on the same kinds of prey as adult and young fish, so if fish are removed from the equation, jellyfish are likely to move in."[citation needed]

Some jellyfish populations that have shown clear increases in the past few decades are "invasive" species, newly arrived from other parts of the world: examples of regions with troublesome non-native jellyfish include the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, the Baltic Sea, the eastern Mediterranean coasts of Egypt and Israel, and the American coast of the Gulf of Mexico.[citation needed] Populations of some invasive species expand rapidly because there are no natural predators in the ecosystem to check their growth. Such blooms would not necessarily reflect overfishing or other environmental problems.

Increased nutrients in the water, ascribed to agricultural runoff, have also been cited as an antecedent to the proliferation of jellyfish. Monty Graham, of the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama, says that "ecosystems in which there are high levels of nutrients ... provide nourishment for the small organisms on which jellyfish feed. In waters where there is eutrophication, low oxygen levels often result, favoring jellyfish as they thrive in less oxygen-rich water than fish can tolerate. The fact that jellyfish are increasing is a symptom of something happening in the ecosystem."[4]

By sampling sea life in a heavily fished region off the coast of Namibia, researchers found that jellyfish have overtaken fish in terms of biomass. The findings represent a careful, quantitative analysis of what has been called a "jellyfish explosion" following intense fishing in the area in the last few decades. The findings were reported by Andrew Brierley of the University of St. Andrews and his colleagues in the July 11, 2006 issue of the journal Current Biology[5].

Areas which have been seriously affected by jellyfish blooms include the northern Gulf of Mexico. In that case, Graham states, "Moon jellies have formed a kind of gelatinous net that stretches from end to end across the gulf."[4]

Life cycle

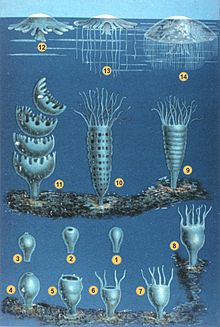

Most jellyfish undergo two distinct life history stages (body forms) during their life cycle. The first is the polypoid stage, when the animal takes the form of a small stalk with feeding tentacles; this polyp may be sessile, living on the bottom or on similar substrata such as floats or boat-bottoms, or it may be free-floating or attached to tiny bits of free-living plankton or even (rarely) fish.[citation needed] Polyps generally have a mouth surrounded by tentacles that face upwards, like miniatures of the closely-related anthozoan polyps (sea anemones and corals), also of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish polyps may be solitary or colonial, and some bud asexually by various means, making more polyps. Most are very small, measured in millimeters or a fraction of an inch tall.

In the second stage, the tiny polyps asexually produce jellyfish, each of which is also known as a medusa. Tiny jellyfish (usually only a millimeter or two across) pull away from the polyp by swimming, and then grow and feed in the plankton.[citation needed] Medusae have a radially symmetric, umbrella-shaped body called a bell, which is usually supplied with marginal tentacles - fringe-like protrusions from the border of the bell that are used to capture prey. A few species of jellyfish do not have the polyp portion of the life cycle, but go from jellyfish to the next generation of jellyfish through direct development of the fertilized eggs.

Jellyfish are dioecious; that is, they are either male or female. In most cases, to reproduce, both males and females release sperm and eggs into the surrounding water, where the (unprotected) eggs are fertilized and mature into new organisms. In a few species, the sperm swim into the mouth of the female, allowing the fertilization of the ova within the female's body. Moon jellies use a different process, in which the eggs become lodged in pits on the oral arms, which form a temporary brood chamber to accommodate fertilization and early development.

After fertilization and initial growth, a larval form, called the planula, develops from the egg. The planula is a small larva covered with cilia. It settles onto a firm surface and develops into a polyp. The polyp is cup-shaped with tentacles surrounding a single orifice, resembling a tiny sea anemone.[citation needed] After an interval of growth, the polyp begins reproducing asexually by budding and, in the Scyphozoa, is called a segmenting polyp, or a scyphistoma. New scyphistomae may be produced by budding or new, immature jellies called ephyrae may be formed. A few jellyfish species are also capable of producing new medusae by budding directly from the medusan stage; such budding has been described from the tentacle bulbs, the manubrium (above the mouth), or the gonads of hydromedusae (each species buds only from one location). Fission of medusae (splitting in half) has been described for a few of species of hydromedusae.

Some of the most common and important jellyfish predators are other species of jellyfish, some of which are specialists in eating jellies. Other predators of jellyfish include tuna, shark, swordfish, and at least one species of Pacific salmon, as well as sea turtles. Sea birds sometimes pick symbiotic crustaceans from the bells of jellyfish near the surface of the sea, inevitably feeding also on the jellyfish hosts of these amphipods or young crabs and shrimp.

Jellyfish lifespans typically range from a few hours (in the case of some very small hydromedusae) to several months. The life span and maximum size of each species is unique. One unusual species is reported to live as long as 30 years and another species, Turritopsis dohrnii as T. nutricula, is said to be effectively immortal because of its ability to transform between medusa and polyp, thereby escaping death.[6] Most of the large coastal jellyfish live about 2 to 6 months, during which they grow from a millimeter or two to many centimeters in diameter. They feed continuously and grow to adult size fairly rapidly. After reaching adult size (which varies by species), jellyfish spawn daily if there is enough food in the ecosystem. In most jellyfish species, spawning is controlled by light, so the entire population spawns at about the same time of day, often at either dusk or dawn[7].

Importance to humans

Culinary uses

Only scyphozoan jellyfish belonging to the order Rhizostomeae are harvested for food; about 12 of the approximately 85 known species of Rhizostomeae are being harvested and sold on international markets. Most of the harvest takes place in southeast Asia[8]. Rhizostomes, especially Rhopilema esculentum in China (Chinese name: 海蜇 hǎizhē, meaning "sea sting") and Stomolophus meleagris (cannonball jellyfish) in the United States, are favored because they are typically larger and have more rigid bodies than other scyphozoans. Furthermore, their toxins are harmless to humans.[9]

Traditional processing methods, carried out by a Jellyfish Master, involve a 20 to 40 day multi-phase procedure in which the umbrella and oral arms are treated with a mixture of table salt and alum, and compressed.[9] The gonads and mucous membranes are removed prior to salting. Processing reduces liquidation, off-odors and the growth of spoilage organisms, and makes the jellyfish drier and more acidic, producing a "crunchy and crispy texture."[9] Jellyfish prepared this way retain 7-10% of their original, raw weight, and the processed product contains approximately 94% water and 6% protein.[9] Freshly processed jellyfish has a white, creamy color and turns yellow or brown during prolonged storage.

In China, processed jellyfish are desalted by soaking in water overnight and eaten cooked or raw. The dish is often served shredded with a dressing of oil, soy sauce, vinegar and sugar, or as a salad with vegetables.[9] In Japan, cured jellyfish are rinsed, cut into strips and served with vinegar as an appetizer.[9][10] Desalted, ready-to-eat products are also available.[9]

Fisheries have begun harvesting the American cannonball jellyfish, Stomolophus meleagris, along the southern Atlantic coast of the United States and in the Gulf of Mexico for export to Asian nations.[9]

In biotechnology

In 1961, green fluorescent protein (GFP) and another bioluminescent protein, called aequorin, were extracted from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria by Osamu Shimomura of Princeton University, who was studying photoproteins which cause the jellyfish's bioluminescence. Three decades later, Douglas Prasher, a post-doctoral scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, sequenced and cloned the gene for GFP and made it available for other scientists to use. It was immediately found to be interesting by scientists with diverse interests and diverse biological preparations. Martin Chalfie of Columbia University figured out how to use GFP as a fluorescent marker of genes inserted into other cells or organisms. Roger Tsien of University of California, San Diego, chemically manipulated GFP in order to get other colors of fluorescence to use as markers. In 2008, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie, and Roger Tsien for their work with GFP.

Manmade green fluorescent protein (which was discovered in the jellyfish Aequorea victoria and subsequently cloned) has become a useful tool in biological science and medicine. It is used as a fluorescent tag to show in which cells or tissues certain genes are expressed. The technique, using genetic engineering, fuses the gene of interest to the gene of GFP. The fused DNA is then put into a cell, to generate either a cell line or (via IVF techniques) an entire animal bearing the gene. In the cell or animal, the artificial gene gets turned on in the same tissues and the same time as the normal gene. But instead of making the normal protein, the gene makes GFP. One can then find out what tissues express that protein—or at what stage of development—by shining light on the animal or cell, and looking for the green fluorescence. The fluorescence shows where the gene of interest is expressed.[11]

Jellyfish are also harvested for their collagen, which can be used for a variety of scientific applications including the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

In captivity

Jellyfish are commonly displayed in aquariums in many countries. Often the tank's background is blue and the animals are illuminated by side light to produce a high contrast effect. In natural conditions, many jellies are so transparent that they are nearly invisible.

Holding jellyfish in captivity presents other problems. For one, they are not adapted to closed spaces. They depend on currents to transport them from place to place. To compensate for this, professional exhibits feature precise water flows, typically in circular tanks to prevent specimens from becoming trapped in corners. The Monterey Bay Aquarium uses a modified version of the kreisel (German for "spinning top") for this purpose.

Toxicity to humans

Victims of jellyfish stings may require first aid immediately. The stings of Scyphozoan jellyfish are not generally deadly, though some species of the completely separate class Cubozoa (box jellyfish), such as the famous and especially toxic Irukandji, can be. However, even nonfatal jellyfish stings are known to be extremely painful. Serious stings may cause anaphylaxis, which may result in death. Hence, people stung by jellyfish must get out of the water to avoid drowning. In serious cases, advanced professional care must be sought. This care may include administration of an antivenin and other supportive care such as required to treat the symptoms of anaphylactic shock.

There are three goals of first aid for uncomplicated jellyfish stings: prevent injury to rescuers, inactivate the nematocysts, and remove any tentacles stuck on the patient. To prevent injury to rescuers, barrier clothing should be worn. This protection may include anything from panty hose to wet suits to full-body sting-proof suits. Inactivating the nematocysts, or stinging cells, prevents further injection of venom into the patient.

Vinegar (3 to 10% aqueous acetic acid) should be applied for box jellyfish stings.[12][13] Vinegar, however, is not recommended for Portuguese Man o' War stings.[12] In the case of stings on or around the eyes, vinegar may be placed on a towel and dabbed around the eyes, but not in them. Salt water may also be used in case vinegar is not readily available.[12][14] Fresh water should not be used if the sting occurred in salt water, as a change in Tonicity[15] can cause the release of additional venom. Rubbing the wound, or using alcohol, spirits, ammonia, or urine will encourage the release of venom and should be avoided.[16] A strange but effective method of treatment of stings is meat tenderizer which efficiently removes the nematocysts[citation needed]. Though often not available, a shower or bath as hot as can be tolerated can neutralize stings. However, if hypothermia is suspected this method may cause other serious complications.

The stinging cells cannot be removed by simply removing the tentacles. Clearing the area of jelly, tentacles, and wetness will disable further nematocyst firing.[16] First aid providers should be careful to use gloves or another readily available barrier device to prevent personal injury, and to follow standard universal precautions. After large pieces of the jellyfish are removed, shaving cream may be applied to the area and a knife edge, safety razor, or credit card may be used to take away any remaining nematocysts.[17]

Beyond initial first aid, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) may be used to control skin irritation (pruritus).[17] To remove the venom in the skin, apply a paste of baking soda and water and apply a cloth covering on the sting. If possible, reapply paste every 15–20 minutes. Ice can be applied to stop the spread of venom until either of these is available.

New discoveries

Research into jellyfish taxonomy and life cycles has increased due to greater contact with humans and the reasonable point of their danger to humans. The many new discoveries that have been made about jellyfish and their popularity as symbol of the beauty and fragility of the oceans are reflected in even television specials, such as in "Jellyfish Invasion," a one-hour episode of the National Geographic Channel documentary series Explorer,[18][19][20] which includes research conducted by scientists in Australia, Hawaii and Japan. Among the latest discoveries, some of which contradict what was previously believed about these creatures, are:

- While it had been previously established that the box jellyfish has four stomachs or gastric pouches, four eyes appear as small spots on each side of its bell, the circular umbrella like body which propels through water, allowing the inverterbrae to have 360 degree vision, it has been found that it also has four separate brains which appear to compete for dominance, as well as four clusters of six well-developed eyes. These eyes allow them to consciously hunt for their prey, as well as to use landmarks outside the water to navigate by. There is also a suggestion that they have colour perception, a test with coloured objects placed in the water showed the jellyfish bumping into white-coloured objects, navigating around black-coloured ones and shying away from red.

- The turritopsis nutricula jellyfish appears to be immortal, rejuvenating itself after it becomes an adult.[21]

Taxonomic classification systematics

Taxonomic classification systematics within the Cnidaria, as with all organisms, are always in flux. Many scientists who work on relationships between these groups are reluctant to assign ranks, although there is general agreement on the different groups, regardless of their absolute rank. Presented here is one scheme, which includes all groups that produce medusae (jellyfish), derived from several expert sources:

Phylum Cnidaria

- Subphylum Medusozoa

- Class Hydrozoa [22][23]

- Subclass Hydroidolina

- Order Anthomedusae (= Anthoathecata or Athecata)

- Order Leptomedusae (= Leptothecata or Thecata)

- Suborder Conica - see [22] for families

- Suborder Proboscoida - see [22] for families

- Order Siphonophorae

- Suborder Physonectae

- Families: Agalmatidae, Apolemiidae, Erennidae, Forskaliidae, Physophoridae, Pyrostephidae, Rhodaliidae

- Suborder Calycophorae

- Families: Abylidae, Clausophyidae, Diphyidae, Hippopodiidae, Prayidae, Sphaeronectidae

- Suborder Cystonectae

- Families: Physaliidae, Rhizophysidae

- Suborder Physonectae

- Subclass Trachylina

- Order Limnomedusae

- Families: Olindiidae, Monobrachiidae, Microhydrulidae, Armorhydridae

- Order Trachymedusae

- Families: Geryoniidae, Halicreatidae, Petasidae, Ptychogastriidae, Rhopalonematidae

- Order Narcomedusae

- Families: Cuninidae, Solmarisidae, Aeginidae, Tetraplatiidae

- Order Actinulidae

- Families: Halammohydridae, Otohydridae

- Order Limnomedusae

- Subclass Hydroidolina

- Class Staurozoa (= Stauromedusae) [24]

- Order Eleutherocarpida

- Families: Lucernariidae, Kishinouyeidae, Lipkeidae, Kyopodiidae

- Order Cleistocarpida

- Families: Depastridae, Thaumatoscyphidae, Craterolophinae

- Order Eleutherocarpida

- Class Cubozoa [25]

- Families: Carybdeidae, Alatinidae, Tamoyidae, Chirodropidae, Chiropsalmidae

- Class Scyphozoa [25]

- Order Coronatae

- Families: Atollidae, Atorellidae, Linuchidae, Nausithoidae, Paraphyllinidae, Periphyllidae

- Order Semaeostomeae

- Families: Cyaneidae, Pelagiidae, Ulmaridae

- Order Rhizostomeae

- Order Coronatae

- Class Hydrozoa [22][23]

Gallery

-

Pacific sea nettle jellyfish Chrysaora fuscescens.

-

Upside-down jellyfish harbor algae in their tentacles which they turn up to the sun to promote photosynthesis.

-

Chrysaora colorata, the purple-striped jellyfish, lives off the coast of Southern California.

-

Olindias sp.

-

The Lion's mane jellyfish, Cyanea capillata, is known for its painful, but rarely fatal, sting.

-

A species of Mediterranean jellyfish, Cotylorhiza tuberculata, on display at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

-

Medusa Jellyfish

-

Aurelia aurita

See also

- Jellyfish dermatitis

- Turritopsis nutricula, an immortal jellyfish

- Sea nettle

- Irukandji jellyfish

- Moon jelly

- Phacellophora camtschatica

- Cubozoa (the box jellyfish)

- Cassiopea

- Cotylorhiza tuberculata

- Pelagia noctiluca (jellyfish mainly found in British water and Mediterranean)

- Craspedacusta sowerbyi, a freshwater jellyfish

- Lion's mane jellyfish, with the longest known tentacles (over 100 feet)

- Portuguese Man o' War, commonly but erroneously thought of and referred to as jellyfish, actually a colony of organisms

- Ocean sunfish, predator of jellyfish

- Aequorea tenuis (the flat jellyfish)

References

- ^ Marques, A.C. and A. G. Collins, 2004. Cladistic analysis of Medusozoa and cnidarian evolution. Invertebrate Biology 123: 23-42.

- ^ Kramp, P.L. 1961. Synopsis of the Medusae of the World. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 40: 1-469 and many subsequent descriptions of new species.

- ^ a b Mills, C.E. 2001. Jellyfish blooms: are populations increasing globally in response to changing ocean conditions? Hydrobiologia 451: 55-68.

- ^ a b The Washington Post, republished in the European Cetacean Bycatch Campaign, Jellyfish “blooms” could be sign of ailing seas, May 6, 2002. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ Lynam, C. and six other authors, 2006. Jellyfish overtake fish in a heavily fished ecosystem. Current Biology 16, no. 13: R492-R493.

- ^ Piraino, S. et al. 1996. Reversing the life cycle: medusae transforming into polyps and cell transdifferentiation in Turritopsis nutricula (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). Biological Bulletin 190: 302-312.

- ^ Mills, Claudia (1983). "Vertical migration and diel activity patterns of hydromedusae: studies in a large tank". Journal of Plankton Research. 5: 619–635.

- ^ Omori, M. and E. Nakano, 2001. Jellyfish fisheries in southeast Asia. Hydrobiologia 451: 19-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Y-H. Peggy Hsieh, Fui-Ming Leong, and Jack Rudloe (2004). "Jellyfish as food". Hydrobiologia. 451 (1–3): 11–17. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Firth, F.E. (1969). The Encyclopedia of Marine Resources. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. New York. ISBN 0442223994.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Pieribone, V. and D.F. Gruber (2006). Aglow in the Dark: The Revolutionary Science of Biofluorescence. Harvard University Press. pp. 288p.

- ^ a b c Fenner P, Williamson J, Burnett J, Rifkin J (1993). "First aid treatment of jellyfish stings in Australia. Response to a newly differentiated species". Med J Aust. 158 (7): 498–501. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 8469205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Currie B, Ho S, Alderslade P (1993). "Box-jellyfish, Coca-Cola and old wine". Med J Aust. 158 (12): 868. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 8100984.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yoshimoto C (2006). "Jellyfish species distinction has treatment implications". Am Fam Physician. 73 (3): 391. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 16477882.

- ^ http://www.healthline.com/blogs/outdoor_health/2008/01/meat-tenderizer-for-jellyfish-sting.html

- ^ a b Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J (1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". Med J Aust. 1 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 6102347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Perkins R, Morgan S (2004). "Poisoning, envenomation, and trauma from marine creatures". Am Fam Physician. 69 (4): 885–90. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415. PMID 14989575.

- ^ Jellyfish Invasion, National Geographic, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ Jellyfish Invasion, YouTube, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ Killer jellyfish population explosion warning, The Daily Telegraph, 11 Feb 2008, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ Turritopsis nutricula: the world's only 'immortal' creature, The Times, 26 Jan 2009, retrieved Feb 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Schuchert, Peter. "The Hydrozoa Directory". Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ Mills, C.E., D.R. Calder, A.C. Marques, A.E. Migotto, S.H.D. Haddock, C.W. Dunn and P.R. Pugh, 2007. Combined species list of Hydroids, Hydromedusae, and Siphonophores. pp. 151-168. In Light and Smith's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. Fourth Edition (J.T. Carlton, editor). University of California Press, Berkeley.

- ^ Mills, Claudia E. "Stauromedusae: List of all valid species names". Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ^ a b Dawson, Michael N. "The Scyphozoan". Retrieved 2008-08-11.

External links

- Video of various Jellyfish species at the Monterey Bay Aquarium

- Scyphozoan Jellyfish

- Jellyfish and Other Gelatinous Zooplankton

- Jellyfish Facts - Information on Jellyfish and Jellyfish Safety

- Hydromedusae

- Stauromedusae / Staurozoa

- Cotylorhiza tuberculata

- Treatment of Coelenterate and Jellyfish Envenomations

- British Marine Life Study Society - Jellyfish Page

- Jellyfish - Curious creatures of the sea

- Sting treatment

- Jellyfish Grown with Twelve Heads

- Jellyfish Boom Driven Partly by Warming Waters

- Jellyfish Invasion of seacoast deadzones explained by anthropogenic estuarial pseudoeutrophication