Juan Manuel de Rosas: Difference between revisions

BarrelProof (talk | contribs) I'm having difficulty following the timeline of when this "terrorism" began and ended. The dates seem to overlap. Tagging some relevant statements to prompt clarification. |

→top: O'Donnell is patently WP:FRINGE as has previously been established at Arbcom, please do not reinsert this or other revisionismo sources |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

'''Juan Manuel de Rosas''' (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws",{{efn-ua|The full title was "Restorer of the Laws and Institutions of the Province of Buenos Aires". It was given to Rosas by the House of Representatives of Buenos Aires on 18 December 1829.{{sfn|Sala de Representantes de la Provincia de Buenos Aires|1842|p=3}} After the [[Desert Campaign (1833–34)]] he was called the "Conqueror of the desert" (''Conquistador del desierto'').{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=19}} As his dictatorship became more repressive, Rosas became known as the "Tiger of Palermo", after his main residence in [[Palermo, Buenos Aires|Palermo]], then located outside the town of Buenos Aires.{{sfn|Lynch|1981|p=9}}}} was a politician, army officer and [[caudillo]] who ruled the [[Argentine Confederation]] almost uninterruptedly from 1829 until 1852. He fled from [[Buenos Aires Province|Buenos Aires]] and lived in exile for 20 years in England, where he died in [[Southampton]] in 1877. |

'''Juan Manuel de Rosas''' (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws",{{efn-ua|The full title was "Restorer of the Laws and Institutions of the Province of Buenos Aires". It was given to Rosas by the House of Representatives of Buenos Aires on 18 December 1829.{{sfn|Sala de Representantes de la Provincia de Buenos Aires|1842|p=3}} After the [[Desert Campaign (1833–34)]] he was called the "Conqueror of the desert" (''Conquistador del desierto'').{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=19}} As his dictatorship became more repressive, Rosas became known as the "Tiger of Palermo", after his main residence in [[Palermo, Buenos Aires|Palermo]], then located outside the town of Buenos Aires.{{sfn|Lynch|1981|p=9}}}} was a politician, army officer and [[caudillo]] who ruled the [[Argentine Confederation]] almost uninterruptedly from 1829 until 1852. He fled from [[Buenos Aires Province|Buenos Aires]] and lived in exile for 20 years in England, where he died in [[Southampton]] in 1877. |

||

Rosas is one of the most prominent figures in the history of Argentina, and he remains a highly controversial one. Some historians credit Rosas for bringing unity in a time of anarchy and paving the way for the formation of a State, |

Rosas is one of the most prominent figures in the history of Argentina, and he remains a highly controversial one. Some historians credit Rosas for bringing unity in a time of anarchy and paving the way for the formation of a State,{{sfn|Edwards|2008|p=27}} while others focus on Rosas's authoritarianism and large landholdings and criticize him for resorting to violence, oppression, and even the torture and murder of his opponents.{{sfn|Edwards|2008|p=27}} |

||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Revision as of 17:40, 6 October 2014

Juan Manuel de Rosas | |

|---|---|

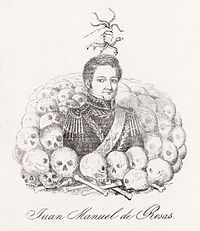

Posthumous portrait of Juan Manuel de Rosas. He is wearing the full dress of a brigadier general. | |

| 17th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 7 March 1835 – 3 February 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Vicente Maza |

| Succeeded by | Vicente López y Planes |

| 13th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 6 December 1829 – 5 December 1832 | |

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas 30 March 1793 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata |

| Died | 14 March 1877 (aged 83) Southampton, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Encarnación Ezcurra |

| Children |

|

| Signature |  |

Juan Manuel de Rosas (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws",[A] was a politician, army officer and caudillo who ruled the Argentine Confederation almost uninterruptedly from 1829 until 1852. He fled from Buenos Aires and lived in exile for 20 years in England, where he died in Southampton in 1877.

Rosas is one of the most prominent figures in the history of Argentina, and he remains a highly controversial one. Some historians credit Rosas for bringing unity in a time of anarchy and paving the way for the formation of a State,[4] while others focus on Rosas's authoritarianism and large landholdings and criticize him for resorting to violence, oppression, and even the torture and murder of his opponents.[4]

Early life

Birth

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas[B] was born on 30 March 1793 at his family's town house in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.[6] He was the first child of León Ortiz de Rosas and Augustina López de Osornio.[7] León Ortiz was the son of an immigrant from the Spanish Province of Burgos who had an undistinguished military career and married into a wealthy Creole family. The greatest influence on young Juan Manuel de Rosas was his mother Augustina, a strong-willed and domineering woman who derived these character traits from her father, "a tough warrior of the Indian frontier who had died weapons in hand defending his southern estate in 1783."[7]

Rosas was schooled at home, as was then common. Later, at age 8, he was enrolled in the finest private school in Buenos Aires. His education was unremarkable, though befitting a son of a wealthy landowner. According to historian John Lynch, it "was supplemented by his own efforts in the years that followed. Rosas was not entirely unread, though the time, the place, and his own bias limited the choice of authors. He appears to have had a sympathetic, if superficial, acquaintance with minor political thinkers of French absolutism."[6]

In 1806, a British expeditionary force was dispatched to the Río de la Plata. A 13-year-old Rosas served in a force, organized by Viceroy Santiago Liniers to counter the invasion, distributing ammunition to troops. The British were defeated in August 1806. The British returned in 1807, and Rosas was assigned to the Caballería de los Migueletes (militia cavalry), although it is thought that he was barred from active duty during this time due to illness.[6]

Estanciero

After the British invasions had been repelled, Rosas departed Buenos Aires with his parents for his family estancia (ranch). His work on the estancia further shaped his character, grounding him in the Platine region's Hispanic-American social framework. In the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, owners of large landholdings (including the Rosas family) provided food, equipment and protection both for themselves and for families living in areas under their control. Their private defense forces consisted primarily of laborers who were drafted as soldiers. Most of these peons, as such workers were called, were gauchos.[C]

For the landed aristocracy of Spanish descent, the illiterate, mixed-race gauchos comprising the majority of the population were an ungovernable and untrustworthy sort. They were treated with contempt by landowners, yet tolerated because there was no other labor force available. Rosas got along well with the gauchos under his service, despite his harsh and authoritarian comportment. He dressed liked them, joked with them, took part in their horse-play, shared their habits and paid them well.[9] He never allowed them to forget, however, that he was their master, rather than their equal.[10] Shaped by the colonial society in which he lived, Rosas was conservative in essence and an advocate of hierarchy and authority.[11] He was, thus, merely a product of his time and not at all unlike the other great landowners in the Río de la Plata region.[12]

Rosas gathered a working knowledge of administration and took charge of his family's estancias beginning in 1811. He was married to Encarnación Ezcurra, the daughter of wealthy Buenos Aires parents, in 1813. He soon afterward sought to forge a career for himself, leaving his parent's estate.[D] He delved into the production of salted meat and began acquiring real property. As the years passed he became an estanciero (rancher) in his own right, accumulating land while establishing a successful partnership with his second cousins, the Anchorenas.[14] His hard work and organizational skills in deploying labor were key to his success, rather than the employment of creative approaches to production.[15]

Rise to power

Caudillo

The May Revolution of 1810 marked the early stages that would later lead to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata's independence from Spain. Rosas, like many landowners in the countryside, was suspicious of a movement advanced primarily by merchants and bureaucrats in the city of Buenos Aires. Rosas was specially outraged by the execution of Viceroy Santiago Liniers at the hands of the revolutionaries. Like many landowners, Rosas was nostalgic of the colonial times and saw them as stable, orderly and prosperous times.[16][17]

When the Congress of Tucumán severed all remaining ties with Spain in July 1816, Rosas and his peers accepted independence as an accomplished fact.[16] With independence came a breakup of the territories which had formed the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires and the other provinces clashed over the power to be turned over to the central government versus the amount of autonomy to be preserved by provincial governments. The Unitarian Party supported Buenos Aires preponderance while the Federalist Party defended provincial autonomy. A decade of strife over the issue destroyed the ties between capital and provinces, with new republics being declared throughout the country. Efforts by the Buenos Aires government to quash these independent states were met by determined local resistance.[18] In 1820 Rosas and his gauchos, all dressed in red which gave them the nickname "Colorados del Monte" ("Reds of the Mount"), enlisted in the army of Buenos Aires as the Fifth Regiment of Militia. They repulsed invading provincial armies, saving Buenos Aires.[19]

At the end of the conflict, Rosas returned to his estancias and remained there. He acquired prestige, was given the rank of cavalry colonel and was awarded further landholdings by the government.[20][21] These additions, together with his successful business and fresh property acquisitions, greatly boosted his wealth. By 1830, he was the 10th largest landowner in the province of Buenos Aires (in which the city of the same name was located), owning 300,000 head of cattle and 420,000 acres (170,000 ha) of land.[22][23] With his newly gained influence, military background, vast landholdings and a private army of gauchos loyal only to him, Rosas became the quintessential caudillo, as provincial warlords in the region were known.[24]

Governor of Buenos Aires

National unity crumbled under the weight of a continuous round of civil wars, rebellions and coups. The Unitarian–Federalist struggle brought perennial instability while caudillos fought for power, laying waste to the countryside. By 1826, Rosas had built a power base, consisting of relatives, friends and clients, and joined the Federalist Party.[25][26] He remained a stalwart advocate of his native province of Buenos Aires, and political ideology was of little concern to him.[25][27] In 1820, Rosas fought alongside the Unitarians because he saw the Federalist invasion as a menace to Buenos Aires. When the Unitarians sought to appease the Federalists by proposing to grant the other provinces a share in the customs revenues flowing through Buenos Aires, Rosas saw this as a threat to his province's interests.[25] In 1827, four provinces led by Federalist caudillos rebelled against the Unitarian government. Rosas was the driving force behind the Federalist take-over of Buenos Aires and the election of Manuel Dorrego as provincial governor.[25] Rosas was awarded with the post of general commander of the rural militias of the province of Buenos Aires on 14 July, which increased his influence and power.[25]

In December 1828, the Unitarian Juan Lavalle seized and executed Dorrego.[28] With Dorrego gone, Rosas filled the vacant Federalist leadership and rebelled against the Unitarians. He allied with Estanislao López, caudillo and ruler of Santa Fe Province, and they defeated Lavalle at the Battle of Márquez Bridge in April 1829.[29][30] When Rosas entered the city of Buenos Aires in November of that year, he was hailed both as a victorious military leader and as the head of the Federalists.[29] Rosas was considered a handsome man,[31][32] standing 1.77 meters (5 ft 10 in) tall[33] with blond hair and "piercing blue eyes".[34] Charles Darwin, who met him during his circumnavigation aboard HMS Beagle, assessed him as "a man of extraordinary character."[E] British diplomat Henry Southern said that in "appearance Rosas resembles an English gentleman farmer—his manners are courteous without being refined. He is affable and agreeable in conversation, which however nearly always turns on himself, but his tone is pleasant and agreeable enough. His memory is stupendous: and his accuracy in all points of detail never failing."[36]

On 6 December 1829, the House of Representatives of Buenos Aires elected Rosas governor and granted him facultades extraordinarias (extraordinary powers)—in other words, "unbridled dictatorial powers".[37] This act marked the beginning of his regime, described by historians as a dictatorship.[38] He saw himself as a benevolent despot, saying: "For me the ideal of good government would be paternal autocracy, intelligent, disinterested and infatigable... I have always admired the autocratic dictators who have been the first servants of their people. That is my great title: I have always sought to serve the country."[17][39] He silenced his critics with censorship and banished his enemies.[40] Rosas believed that these measures were necessary, as he later recalled: "When I took over the government I found the government in anarchy, divided into warring factions, reduced to pure chaos, a hell in miniature..."[41]

Desert Campaign

The early administration of Rosas was preoccupied with pressing matters. He had inherited a government saddled by severe deficits, large public debts and currency devaluation.[42] A great drought that began in December 1828, which would last until April 1832, greatly impacted the economy.[43] The Unitarians were still at large, controlling several provinces which had banded together in the Unitarian League. The capture of José María Paz, the main Unitarian leader, in March 1831 resulted in an end to the Unitarian–Federalist civil war and the collapse of the Unitarian League. Rosas was content, for the moment, with granting recognition of provincial autonomy in the Federal Pact.[44][45] In an effort to alleviate the government's financial issues, he improved revenue collection (while not raising taxes) and curtailed expenditures.[46]

By the end of his first term, Rosas was generally credited with having staved off political and financial instability.[44] He still faced increased opposition in the House of Representatives, however. All of the House members were Federalists, as Rosas had restored the legislature that was seated under Dorrego, and which had subsequently been dissolved by Lavalle.[47] A liberal Federalist faction, which accepted dictatorship as a temporary necessity, called for the adoption of a Constitution.[48] Rosas was unwilling to govern constrained by a constitutional framework and only grudgingly relinquished his dictatorial powers. His term of office ended soon after, on 5 December 1832.[44]

While the government in Buenos Aires was distracted with other matters, ranchers had begun moving into territories in the south that were occupied by indigenous peoples. The resulting uncontrolled land grab and conflict with native peoples necessitated a government response.[49] Rosas steadfastly endorsed policies which supported this expansion. During his governorship he had granted lands in the south to war veterans and to ranchers seeking alternative pasture lands during the drought.[50] Although the south was regarded as a virtual desert at the time, it possessed great potential and resources for agricultural development, particularly for ranching operations.[50] The government gave Rosas the command of an army with the directive to subdue the Indian tribes in the coveted territory. Rosas was generous with those Indians who submitted, rewarding them with animals and goods. Although he personally disliked killing Indians, Rosas relentlessly hunted down those who refused to yield.[51] The Desert Campaign lasted from 1833 until 1834, and Rosas successfully subjugated the entire region. The conquest of the south by Rosas opened up many additional possibilities for yet further territorial expansion, and he correctly predicted: "The fine territories, which extend from the Andes to the coast and down to the Magellan Straits are now wide open for our children."[52]

Second governorship

Absolute power

While Rosas was away on the Desert Campaign in October 1833, a group of Rosistas (Rosas's supporters) laid siege to Buenos Aires. Inside the city, Rosas's wife, Encarnación, assembled a contingent of associates to aid the besiegers. The Revolution of the Restorers, as the Rosista coup came to be known, forced the provincial governor Juan Ramón Balcarce to resign. In quick succession, Balcarce was followed by two others who presided over weak and ineffective governments. The Rosismo (Rosism) had become a powerful faction within the Federalist Party, and it pressured other factions to accept a return of Rosas, endowed with dictatorial powers, as the only way to restore stability.[53] The House of Representatives yielded, and on 7 March 1835, Rosas was reelected governor and invested with the suma del poder público (sum of public power).[54][55]

A plebscite was held to determine whether or not the citizens of Buenos Aires city approved of Rosas's reelection and his assumption of dictatorial powers. The result was predictable: 99,9% voted "yes".[56] Under Rosas, the election process had been reduced to a farce. Since 1829, he had installed loyal associates as justices of the peace, powerful officeholders with administrative and judicial functions who were also charged with tax collection, leading militia and presiding over elections.[57] Through the exclusion of voters and intimidation of the opposition, the justices of the peace delivered any result Rosas favored.[58][59] Half of the members of the House of Representatives faced reelection each year, and the opposition quickly vanished due to election-rigging. The legislature became a docile instrument of the will of Rosas. The legislature was stripped of any control over finances and input into legislation brought before it for approval and its rubber stamp was retained largely to provide a democratic veneer and ostensible backing for the governor's dictates.[59][60]

In a country where most of the population was illiterate and uneducated, Rosas argued that rigged elections were the only form compatible with stability.[61] The governor acquired absolute power over the province with the assent and support of most estancieros and businessmen—people who shared his views.[62][63] However, the estancia formed the power base on which Rosas relied. Lynch said that there "was a great deal of group cohesion and solidarity among the landed class. Rosas himself was the center of a vast kinship group based on land. He was surrounded by a closely knit economic and political network linking deputies, law officers, officials, and military who were also landowners and related among themselves or with Rosas."[64]

Totalitarian regime

Rosas's authority and influence spread far beyond the House of Representatives. His cabinet was composed of powerless figures, and Rosas noted: "Do not imagine that my Ministers are any thing but my Secretaries. I put them in their offices to listen and report, and nothing more."[65] He also exercised tight control over the bureaucracy. His supporters were rewarded with positions within the state apparatus, and anyone he deemed a threat was purged.[66][67] Opposition newspapers were burned in public squares.[68] Rosas created an elaborate cult of personality, where he was shaped as an all-mighty and father-like figure who protected the people.[69][70] His portraits were carried in street demonstrations and placed on church altars to be venerated.[71] Rosismo was no longer a mere faction within the Federalist ranks; it had become a political movement. As early as 1829, Rosas confided that he was not a true Federalist: "I tell you I am not a Federalist, and I have never belonged to that party."[43] During his governorship, he still claimed to have favored Federalism against Unitarianism, although in practice Federalism had by that time been subsumed under the Rosismo movement and Unitarianism into the anti-Rosismo term.[69]

The Argentine governor established a totalitarian regime, in which the government sought to dictate every aspect of public and private life. It was mandated that the slogan "Death to the Savage Unitarians" be inscribed at the head of all official documents.[72] Anyone on the state payroll—from military officers, priests, to civil servants and teachers—was obliged to wear a red badge with the inscription "Federation or Death".[73] Every male was supposed to have a "federal look", i.e., to sport a large mustache and sideburns. Many resorted to wearing false mustaches.[74] The red color—symbol of both the Federalist Party and of Rosismo—became omnipresent in the province of Buenos Aires. Soldiers wore red chiripás (blankets worn as trousers), caps and jackets, and their horses sported red accouterments.[74] Civilians were also to wear the color. A red waistcoat, red badge and red hat band were required for men, while women wore ribbons in that color and children donned school uniforms based upon Rosismo paradigms. Building exteriors and interiors were also decorated in red.[75]

Clergy of the Catholic Church in Buenos Aires willingly backed Rosas and his regime.[76] The Jesuits, the only ones who refused to acquiesce, were expelled from the country.[67][77] The lower social strata in Buenos Aires, which formed the vast majority of its populace, experienced no improvement in the conditions under which they lived. When Rosas slashed expenditures, he cut resources from education, social services, general welfare and public works.[78] None of the lands confiscated from Indians and Unitarians were turned over to rural workers (including gauchos).[79] Neither did blacks see any improvement in their lot. Rosas owned slaves and even helped revive slave trade, prior to its eventual ban.[80] Even though he had done little to nothing to promote their interests, he remained highly popular among blacks and gauchos.[81] Rosas did not hold prejudice along racial lines. He employed blacks, patronized their festivities and attended their candombles.[82] The gauchos admired his strong leadership and willingness to fraternize with them (though only to a certain point).[9]

State terrorism

Purges, banishments and censorship were not the only measures Rosas brought to bear against the opposition and anyone else he deemed a threat. He resorted[when?] to what historians have considered state terrorism.[83] Terror was a tool used to intimidate dissident voices, to shore up support among his own partisans and to exterminate his foes.[84][85] His targets were denounced as having ties (real or invented) to Unitarians. Those victimized included members of his own government and party who were suspected of being insufficiently loyal. If actual opponents were not at hand, the regime was capable of finding other quarry who could be punished in order to serve as cautionary examples. A climate of fear was created to underpin unquestioning conformity to the leader's dictates.[86]

A judiciary branch still existed in Buenos Aires. Rosas removed any independence the courts might have exercised, either by controlling appointments to judgeships, or by circumventing their authority entirely. He would sit in judgement over cases on his own; issuing fines, sentencing to service in the army, imprisoning or condemning to death.[87][88] Terrorism was orchestrated rather than a product of popular zeal, was targeted for effect rather than indiscriminate. Anarchic demonstrations, vigilantism and disorderliness were antithetical to a regime touting a law and order agenda, and the exercise of terror was firmly in the hands of Rosas. Not even subordinates who carried out his government's oppressive policies had any authority to enforce them as they saw fit or any discretion as to whom would be persecuted. The state's terror was exercised intermittently, systematically and with focus to enforce the regime's will.[85][89] Foreign residents were exempted from abuses, as were people who were too poor or inconsequential to make effective examples. Victims were selected for their usefulness as tools of intimidation.[85]

State terrorism was carried out by the Mazorca, which was an armed parapolice unit of the Sociedad Popular Restauradora political organization.[when?] The Sociedad Popular Restauradora and the Mazorca were creations of Rosas, who retained tight control over both.[84][90] The tactics of the mazorqueros included neighborhood sweeps in which houses would be searched and occupants intimidated. Others who fell into their power were arrested, tortured and killed.[91] Executions were generally by shooting, lance-thrusting or throat-slitting.[92] Castration, scalping of beards and cutting out tongues were also used.[93] Modern estimates report around 2,000 people were executed from 1829 until 1852.[94]

Apogee and downfall

Rebellions and foreign threat

Throughout the late 1830s and early 1840s, Rosas faced a series of major threats to his power. The Unitarians found an ally in Andrés de Santa Cruz, ruler of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. Rosas declared war on 19 March 1837, joining the War of the Confederation between Chile and Peru–Bolivia. The Rosista army played a minor role in the conflict, which resulted in the overthrow of Santa Cruz and the dissolution of the Peru–Bolivian Confederation.[95] On 28 March 1838, France declared a blockade of the port of the city of Buenos Aires, eager to extend its influence over the troubled region. Unable to confront the French, Rosas strengthened the repression at home, so as to forestall potential uprisings against his regime.[96][97]

The blockade caused severe damage to the economy which spread to all the provinces, as they depended on the port of Buenos Aires to export. Despite the 1831 Federal Pact, all provinces had long been discontented with the de facto primacy Buenos Aires province held over them.[96][97] On 28 February 1839, the province of Corrientes revolted and attacked both Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos provinces. Rosas counterattacked and defeated the rebels, killing their leader, the governor of Corrientes.[96][97] In June, Rosas uncovered a plot by dissident Rosistas to oust him from power in what became known as the Maza conspiracy. Rosas either imprisoned or executed the plotters. Manuel Vicente Maza, president of both the House of Representatives and the Supreme Court, was murdered by Rosas's Mazorca agents within the halls of the parliament on the pretext that his son was involved in the conspiracy.[98] In the countryside, estancieros (including a younger brother of Rosas) revolted, beginning the Rebellion of the South.[99] The rebels attempted an alliance with France, but were easily crushed, many losing their lives and properties in the process.[100]

In September 1839, Juan Lavalle returned after ten years in exile. He allied with Corrientes, which revolted once again, and invaded Buenos Aires province at the head of Unitarian troops armed and supplied by the French. Emboldened by Lavalle's actions, the provinces of Tucumán, Salta, La Rioja, Catamarca and Jujuy formed the Coalition of the North and rebelled against Buenos Aires.[101] Great Britain intervened on behalf of Rosas, and France lifted the blockade on 29 October 1840.[102][103] The struggle with his internal enemies was hard-fought. By December 1842, Lavalle had been killed and the rebellious provinces subdued, excepting Corrientes (only defeated in 1847).[104] Terrorism was also employed[when?] on the battlefield, as the Rosistas refused to take prisoners. Whoever tried to escape was pursued, had their throats cut and heads put on exhibition.[86]

Ruler of Argentina

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Astynax (talk | contribs) 9 years ago. (Update timer) |

Terrorism as an instrument of state repression was over.[when?] On 18 December 1829 Rosas was raised from colonel to brigadier general, the highest army rank.[1] Many years later he declined to accept the newly created and higher rank of grand marshal (gran mariscal), which had been bestowed on him by the House of Representatives on 12 November 1840.[105]

His wife Encarnación had died in October 1838 after a long illness. Although devastated by his loss, Rosas exploited her death to raise support for his regime.[106] Not long after, he began an affair at age 47 with his fifteen-year-old maid, María Eugenia Castro, with whom he had five children.[107] From his marriage to Encarnación, Rosas had two children: Juan Bautista Pedro and Manuela Robustiana. Rosas established a hereditary dictatorship, naming his legitimate children as his hand-picked successors, claiming that "[t]hey are both worthy children of my beloved Encarnación, and if, God willing, I die, then you will find that they are capable of succeeding me."[108] It is unknown whether Rosas was a closeted monarchist, as many other fellow countrymen were before him. Later during his exile Rosas would declare that Princess Alice of the United Kingdom would be the ideal ruler for his country.[109] Nonetheless, in public he claimed that his regime was republican in nature.[110]

When Rosas was elected governor for the first time in 1829, he had no power outside the limits of the province of Buenos Aires. There was no national government nor a national parliament.[111] The former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata had given rise to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, which by the 1831 following the Federal Pact (and officially from 22 May 1835) had been increasingly known as the Argentine Confederation, or simply, Argentina.[112] His victory over the other Argentine provinces in the early 1840s turned them into satellites of Buenos Aires. "In each of the provinces , he managed to gradually impose allied, satellite, or weak governors" and "exercised some de facto control over the provinces".[72] By 1848 Rosas began calling his government the "government of the confederacy" and "general government", which would be inconceivable a few years before. The next year, with the provinces' acceptance, he named himself "Supreme Head of the Confederacy" and became the indisputable ruler of Argentina.[113]

Platine War

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Astynax (talk | contribs) 9 years ago. (Update timer) |

One of his secretariats said: "The dictator is not stupid: he knows the people hate him; he goes in constant fear... He has a horse ready saddled at the door of his office day and night..."[85]

Later years

Exile and death

Rosas arrived in Plymouth, Great Britain, on 26 April 1852. The British gave him asylum, paid for his travel and welcomed him with a 21-gun salute. These honors were granted to him because "General Rosas was no common refugee, but one who had shown great distinction and kindness to the British merchants who had traded with his country", explained James Harris, 3rd Earl of Malmesbury, the British Foreign Secretary.[114] Months before his fall Rosas had arranged with with the British Chargé d'affaires Captain Robert Gore to receive protection and safe haven in case of defeat.[115] Both his children by Encarnación followed him into exile, although Juan Bautista soon returned with his family to Argentina. His daughter Manuela married the son of an old associate of Rosas, an act which the former dictator never forgave. A domineering parent, Rosas wanted his daughter to remain devoted to him alone. Although he forbade her from writing or visiting, Manuela remained loyal to her father and maintained contact with him.[116]

The new Argentine government confiscated all of Rosas properties and tried him as a criminal, later sentencing him to death.[117] Rosas was appalled that most of his friends, supporters and allies abandoned him and became either silent or openly criticized him.[118] Rosismo had vanished overnight. "The landed class, supporters and beneficiaries of Rosas, now had to make their peace—and their profits—with his successors. Survival, not allegiance, was their politics", argued Lynch.[119] Urquiza, a onetime ally and later an enemy, reconciled with Rosas and sent him financial assistance, hoping for political support in return—although Rosas had scant remaining political capital.[120] Rosas followed Argentina's developments while in exile, always hoping an opportunity to return, but he never again insinuated himself into Argentine affairs.[120]

In exile Rosas was not destitute, but he lived modestly amid financial constraints during the remainder of his life.[121] A very few loyal friends sent him money, but it was never enough.[122] He sold one of his estancias before the confiscation and became a British tenant farmer, employing a housekeeper and two to four laborers, to whom he paid above average wages.[123] Despite constant concern over his shortage of funds, Rosas found joy in farm life, once remarking: "I now consider myself happy on this farm, living in modest circumstances as you see, earning a living the hard way by the sweat of my brow".[124] A contemporary described him in final years: "He was then eighty, a man still handsome and imposing; his manners were most refined, and the modest environment did nothing to lessen his air of a great lord, inherited from his family."[125] After a walk on a cold day, Rosas caught pneumonia and died at 07:00 on the morning of 14 March 1877. Following a private mass attended by his family and a few friends, he was buried in the town cemetery of Southampton.[124]

Legacy

Serious attempts to review Rosas's reputation began in the 1880s with the publication of scholarly works by Adolfo Saldías and Ernesto Quesada, but revisionism would only flourish under the Nacionalismo (Nationalism) in the early 20th century. Nacionalismo was a political movement that appeared in Argentina in the 1920s and reached its apex in the 1930s. It was the Argentine equivalent of the authoritarian ideologies that arose during the same period, such as Nazism, Fascism and Integralism. Argentine Nationalism was an authoritarian,[126] anti-Semitic,[127] racist[128] and misogynistic political movement with support for racially-based pseudo-scientific theories such as eugenics.[129] The Revisionismo (Revisionism) was the historiographical wing of Argentine Nacionalismo.[130] The main goal of Argentine Nacionalismo was to establish a national dictatorship. For the Nacionalismo movement, Rosas and his regime were idealized and portrayed as paragons of governmental virtue.[131] Revisionismo served as a useful tool, as the main purpose of the revisionists within the Nacionalismo agenda was to rehabilitate Rosas's image.[132]

Despite a decades-long struggle, the Revisionismo failed to be taken seriously. According to Michael Goebel, the revisionists had a "lack of interest in scholarly standards" and were known for "their institutional marginality in the intellectual field".[133] They also never succeeded in changing mainstream views regarding Rosas. William Spence Robertson said in 1930: "Among the enigmatical personages of the 'Age of Dictators' in South America none played a more spectacular role than the Argentine dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas, whose gigantic and ominous figure bestrode the Plata River for more than twenty years. So despotic was his power that Argentine writers have themselves styled this age of their history as 'The Tyranny of Rosas'."[134] More than 30 years later, in 1961, William Dusenberry said: "Rosas is a negative memory in Argentina. He left behind him the black legend of Argentine history—a legend which Argentines in general wish to forget. There is no monument to him in the entire nation; no park, plaza, or street bears his name."[135]

In the 1980s, Argentina was a broken and deeply divided nation, having faced a military dictatorship and a defeat in the Falklands War. President Carlos Menem decided to repatriate Rosas's remains and take advantage of the occasion to unite the Argentines. Menem believed that if the Argentines could forgive Rosas and his regime, they might do the same regarding the more recent and vividly remembered past.[136] On 30 September 1989, following an elaborate and enormous cortege organized by the government, the remains of the Argentine ruler were interred at his family vault in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires.[137] Politically motivated and in close alliance with neorevisionists, some of Menem's successors in office have honored Rosas on banknotes, postage stamps and monuments, causing mixed reactions among the public.[138][139][140] Rosas remains a controversial figure among Argentines, who "have long been fascinated and outraged" by him.[141][142][143][144]

Endnotes

- ^ The full title was "Restorer of the Laws and Institutions of the Province of Buenos Aires". It was given to Rosas by the House of Representatives of Buenos Aires on 18 December 1829.[1] After the Desert Campaign (1833–34) he was called the "Conqueror of the desert" (Conquistador del desierto).[2] As his dictatorship became more repressive, Rosas became known as the "Tiger of Palermo", after his main residence in Palermo, then located outside the town of Buenos Aires.[3]

- ^ According to his birth certificate, his given name was "Juan Manuel José Domingo". His surname, as seen on his marriage certificate, was "Ortiz de Rosas".[5]

- ^ Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham described them as "herdsmen, who lived on horseback... In their great plains, roamed over by enormous herds of cattle, and countless horses in semi-feral state, each Gaucho lived in his own reed-built rancho [ranch] daubed with mud to make its weathertight often without another neighbor nearer than a league away. His wife and children and possibly two or three other herdsmen, usually unmarried, to help him in the management of the cattle, made up his society. Generally he had some cattle of his own, and possibly a flock of sheep; but the great herds belonged to some proprietor who perhaps lived two or three leagues away."[8]

- ^ An anecdote circulated in which Rosas supposedly related how he left his parents' house with no belongings, determined to start a new life, never to return. The story says that he went so far as to change the spelling of his surname at that point. Rosas denied the version of events contained in this tale.[13] Although he was left a portion of his father's estate, he assigned this to his mother. He did not reclaim the inheritance upon his mother's death, and instead split it between her maid, his siblings and charities.[13]

- ^ Charles Darwin wrote in his journal in 1833: "He is a man of extraordinary character, and has a most predominant influence in the country, which it seems that he will use to its prosperity and advancement." Later, in 1845, he greatly revised his assertion, saying "This prophecy has turned out entirely and miserably wrong."[35]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Sala de Representantes de la Provincia de Buenos Aires 1842, p. 3.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 9.

- ^ a b Edwards 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Pradère 1970, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c Lynch 2001, p. 2.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Graham 1933, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Lynch 1981, p. 14.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 2, 8, 26.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 28.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 3.

- ^ a b Shumay 1993, p. 119.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 18,

- Lynch 2001, p. 9,

- Rock 1987, p. 93.

- ^ See:

- Lynch 2001, p. 9,

- Rock 1987, pp. 93–94, 104,

- Szuchman & Brown 1994, p. 214.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Szuchman & Brown 1994, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bethell 1993, p. 24.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 1, 8, 13, 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e Lynch 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Bethell 1993, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Bethell 1993, pp. 20, 22.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 20,

- Lynch 2001, p. 11,

- Rock 1987, p. 103.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Rock 1987, p. 103.

- ^ Shumay 1993, p. 117.

- ^ Geisler 2005, p. 155.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 125.

- ^ See:

- Castro 2001, p. 69,

- Crow 1980, p. 580,

- Geisler 2005, p. 155,

- Lynch 1981, p. 121,

- Shumay 1993, p. 117.

- ^ Darwin 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 86.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 20,

- Lynch 2001, p. 12,

- Rock 1987, p. 104,

- Shumay 1993, p. 117.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 20,

- Cevasco 2006, p. 29,

- Clayton & Conniff 2005, p. 72,

- Edwards 2008, p. 28,

- Goebel 2011, p. 24,

- Hanway 2003, p. 4,

- Hooker 2008, p. 15,

- Kraay & Whigham 2004, p. 188,

- Leuchars 2002, p. 16,

- Lewis 2003, p. 47,

- Lewis 2006, p. 84,

- Lynch 2001, p. 164,

- Meade 2010, p. 140,

- Rein 1998, p. 73,

- Rock 1987, p. 106,

- Rotker 2002, p. 57,

- Shumay 1993, p. 113,

- Whigham 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 75, 163.

- ^ See:

- Lynch 2001, p. 16,

- Rock 1987, p. 105,

- Shumay 1993, p. 117.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 164.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 22.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Lynch 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Rock 1987, p. 105.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 16, 22.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 49, 159–160, 300.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 17.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 6, 18–20.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 162.

- ^ Rock 1987, p. 106.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 90.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Bethell 1993, p. 26.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 50.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 38–40, 78.

- ^ Shumay 1993, p. 118.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 175.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 82.

- ^ a b Bethell 1993, p. 27.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 180, 184.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Shumay 1993, pp. 118–120.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 27,

- Lynch 1981, pp. 165, 183,

- Shumay 1993, p. 120.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 83.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 27,

- Lynch 1981, p. 178,

- Rock 1987, p. 106.

- ^ a b Lynch 1981, p. 179.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 27,

- Lynch 1981, p. 180,

- Rock 1987, p. 106.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 27,

- Lynch 2001, p. 84,

- Rock 1987, p. 106,

- Shumay 1993, p. 119.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 85.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 22, 91.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 55–56.

- ^ See:

- Bethell 1993, p. 29,

- Hooker 2008, p. 15,

- Lewis 2003, p. 57,

- Loveman 1999, p. 289,

- Lynch 2001, pp. 96, 108, 164,

- Rock 1987, p. 106,

- Shumay 1993, p. 120.

- ^ a b Bethell 1993, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Lynch 2001, p. 96.

- ^ a b Lynch 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 81, 97.

- ^ Bethell 1993, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bethell 1993, p. 30.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 101.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 214.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 118.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b c Lynch 1981, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Bethell 1993, p. 31.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 206.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 205–207.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 207.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Bethell 1993, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Sala de Representantes de la Provincia de Buenos Aires 1842, pp. 169, 179–180.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 373.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 339.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 169.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 262.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 164.

- ^ Lynch 2001, pp. 82, 130.

- ^ Trias 1970, p. 120.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 336.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 337.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 341.

- ^ a b Lynch 1981, p. 342.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 344.

- ^ Lynch 1981, pp. 343–344, 346–347.

- ^ a b Lynch 1981, p. 358.

- ^ Lynch 1981, p. 357.

- ^ See:

- Rock 1995, p. 102;

- Goebel 2011, pp. 43–44;

- Chamosa 2010, pp. 40, 118;

- Nállim 2012, p. 38.

- ^ See:

- Rock 1995, pp. 104–105, 119;

- Goebel 2011, p. 43;

- Chamosa 2010, pp. 40, 118.

- ^ Rock 1995, pp. 103, 106.

- ^ Rock 1995, p. 103.

- ^ See:

- Rock 1995, p. 120;

- Goebel 2011, pp. 7, 48;

- Chamosa 2010, p. 44;

- Nállim 2012, p. 39.

- ^ See:

- Rock 1995, pp. 108, 119;

- Nállim 2012, p. 39;

- Deutsch & Dolkart 1993, p. 15.

- ^ See:

- Johnson 2004, p. 114;

- Goebel 2011, p. 50;

- Miller 1999, p. 224;

- Chamosa 2010, p. 44;

- Nállim 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Goebel 2011, pp. 56, 115–116.

- ^ Robertson 1930, p. 125.

- ^ Dusenberry 1961, p. 514.

- ^ Johnson 2004, pp. 118–125.

- ^ Johnson 2004, pp. 125–128.

- ^ Goebel 2011, pp. 217–218, 220.

- ^ Johnson 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Lanctot 2014, pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. ix.

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 207.

- ^ Johnson 2004, p. 108.

- ^ Chamosa 2010, p. 107.

References

- Bethell, Leslie (1993). Argentina since independence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43376-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Castro, Donald S. (2001). The Afro-Argentine in Argentine Culture: El Negro Del Acordeón. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-7389-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cevasco, Aníbal César (2006). Argentina violenta (in Spanish). Los Angeles: Dunken. ISBN 987-02-1922-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chamosa, Oscar (2010). The Argentine Folklore Movement: Sugar Elites, Criollo Workers, and the Politics of Cultural Nationalism, 1900-1955. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2847-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clayton, Lawrence A.; Conniff, Michael L. (2005). A History of Modern Latin America (2 ed.). Belmont, California: Thomson Learning Academic Resource Center. ISBN 0-534-62158-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crow, John Armstrong (1980). The Epic of Latin America (3 ed.). Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03776-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Darwin, Charles (2008). The Voyage of the Beagle. New York: Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-60520-565-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dusenberry, William (November 1961). "Juan Manuel de Rosas as Viewed by Contemporary American Diplomats". Hispanic American Historical Review. 41 (4). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Deutsch, Sandra McGee; Dolkart, Ronald H. (1993). The Argentine Right: Its History and Intellectual Origins, 1910 to the Present. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 0-8420-2418-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, Todd L. (2008). Argentina: A Global Studies Handbook. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-986-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Geisler, Michael E. (2005). National Symbols, Fractured Identities: Contesting The National Narrative. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 1-58465-436-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goebel, Michael (2011). Argentina's Partisan Past: Nationalism and the Politics of History. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-8463-1238-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graham, Robert Bontine Cunninghame (1933). Portrait of a dictator. London: William Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanway, Nancy . (2003). Embodying Argentina: Body, Space and Nation in 19th Century Narrative. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1457-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hooker, Terry D. (2008). The Paraguayan War. Nottingham: Foundry Books. ISBN 1-901543-15-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Lyman L. (2004). Death, Dismemberment, And Memory: Body Politics In Latin America. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3200-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kraay, Hendrik; Whigham, Thomas (2004). I die with my country: perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870. Dexter, Michigan: Thomson-Shore. ISBN 978-0-8032-2762-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lanctot, Brendan (2014). Beyond Civilization and Barbarism: Culture and Politics in Postrevolutionary Argentina. Lanham, Maryland: Bucknell University Press/Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-61148-545-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leuchars, Chris (2002). To the bitter end: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32365-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, Daniel K. (2003). The History of Argentina. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6254-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, Paul H. (2006). Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America: Dictators, Despots, And Tyrants. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-3739-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loveman, Brian (1999). For la Patria: Politics and the Armed Forces in Latin America. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 0-8420-2772-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lynch, John (1981). Argentine dictator: Juan Manuel De Rosas, 1829–1852. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1982-1129-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lynch, John (2001). Argentine Caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas (2 ed.). Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 0-8420-2897-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meade, Teresa A. (2010). In the Shadow of the State: Intellectuals and the Quest for National Identity in Twentieth-century Spanish America. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2050-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, Nicola (1999). In the Shadow of the State: Intellectuals and the Quest for National Identity in Twentieth-century Spanish America. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-738-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nállim, Jorge (2012). Transformations and Crisis of Liberalism in Argentina, 1930-1955. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-6203-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pradère, Juan A. (1970). Juan Manuel de Rosas, su iconografía (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Buenos Aires: Editorial Oriente.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rein, Mónica Esti (1998). Politics and Education in Argentina: 1946-1962. New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0209-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Robertson, William Spence (May 1930). Foreign Estimates of the Argentine Dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas. Vol. 10. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rock, David (1987). Argentina, 1516–1987: From Spanish Colonization to Alfonsín. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06178-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rock, David (1995). Authoritarian Argentina: The Nationalist Movement, Its History and Its Impact. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20352-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rotker, Susana (2002). Captive Women: Oblivion and Memory in Argentina. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4029-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trias, Vivian (1970). Juan Manuel de Rosas (in Spanish). Montevideo: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and early conduct. Vol. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4786-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sala de Representantes de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (1842). Rasgos de la vida publica de S. E. el sr. brigadier general d. Juan Manuel de Rosas (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Imprenta del Estado.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shumay, Nicolas (1993). The Invention of Argentina. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08284-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Szuchman, Mark D.; Brown, Jonathan Charles (1994). Revolution and Restoration: The Rearrangement of Power in Argentina, 1776–1860. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4228-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)