Julio Cortázar: Difference between revisions

Tag: section blanking |

m Reverted edits by 164.92.9.21 (talk) to last version by John |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

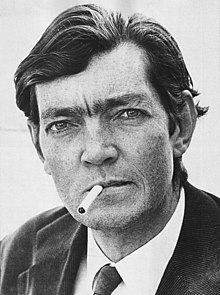

'''Julio Cortázar''', born Jules Florencio Cortázar, (August 26, 1914 – February 12, 1984) was an Argentine author of [[novel]]s and [[short story|short stories]]. He influenced an entire generation of Latin American writers from Mexico to Argentina, and most of his best-known work was written in France, where he established himself in 1951. |

'''Julio Cortázar''', born Jules Florencio Cortázar, (August 26, 1914 – February 12, 1984) was an Argentine author of [[novel]]s and [[short story|short stories]]. He influenced an entire generation of Latin American writers from Mexico to Argentina, and most of his best-known work was written in France, where he established himself in 1951. |

||

==Early life== |

|||

{{Cleanup|date=August 2008}} |

|||

Cortázar was born in [[Brussels]], [[Belgium]] on August 26, 1914 a few days after the invasion of Belgium by Germany at the start of World War I. His father, Julio José Cortázar, was the European commercial representative for the family of his wife, María Herminia Descotte, and the couple had arrived in Belgium in 1913.<ref>Cortázar sin barba, by [[Eduardo Montes-Bradley]]. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004</ref> They were both Argentine. As Cortázar himself put it, his "birth was a product of tourism and diplomacy."<ref>Televisión Española, Serie A Fondo. Interview by: Joaquin Soler Serrano.</ref> |

|||

Soon after the child's birth the family traveled via [[Frankfurt]] to [[Zürich]], where they were reunited with María Herminia's parents: Victoria Gabel, who was a German citizen, and her lover, Descotte, who was a French citizen at a time when Frenchmen were not welcome in Belgium. The family spent two years in Switzerland, spent a short time in [[Barcelona]] towards the end of the war, and then returned to Argentina. |

|||

By then, however, Julio José Cortázar and María Herminia Descotte had split up.<ref>Cortázar sin barba, by [[Eduardo Montes-Bradley]]. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004</ref> Cortázar spent the rest of his childhood in [[Banfield (village)|Banfield]], near [[Buenos Aires]], with his mother and his only sister, who was one year younger. He never saw his father again.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} His childhood home, with its backyard, was a source of inspiration for some of his stories.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} Despite this, he wrote a letter to Graciela M. de Solá (December 4, 1963) describing this period of his life as "full of servitude, excessive touchiness, terrible and frequent sadness." He was a sickly child and spent much of his childhood in bed reading.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} His mother selected what he read, introducing her son most notably to the works of [[Jules Verne]], whom Cortázar admired for the rest of his life. In the magazine ''Plural'' (issue 44, Mexico City, May 1975) he wrote: "I spent my childhood in a haze full of goblins and elfs, with a sense of space and time that was different from everybody else's." |

|||

==Education and teaching career== |

==Education and teaching career== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 31: | ||

==Years in France== |

==Years in France== |

||

In 1951, Cortázar, who was opposed to the government of [[Juan Domingo Perón]],<ref>Cortázar sin barba, by [[Eduardo Montes-Bradley]]. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004</ref> emigrated to France, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life. From 1952 onward, he worked for [[UNESCO]] as a [[translation|translator]]. The projects he worked on included [[Spanish language|Spanish]] renderings of ''[[Robinson Crusoe]]'', [[Marguerite Yourcenar]]'s novel ''[[Mémoires d'Hadrien]]'', and stories by [[Edgar Allan Poe]]. He also came under the influence of the works of [[Alfred Jarry]] and the [[Comte de Lautréamont]], and wrote most of his major works in Paris. In later years he became actively engaged in opposing abuses of [[human rights]] in [[Latin America]], and was a supporter of the [[Sandinista]] revolution in [[Nicaragua]]. |

|||

In 1951, Cortázar, who was novel ''[[ |

|||

Cortázar was married three times, to [[Aurora Bernárdez]], to [[Ugnė Karvelis]], and finally to [[Carol Dunlop]]. He died in Paris in 1984 and is interred in the [[Cimetière de Montparnasse]], next to Carol Dunlop. The cause of his death was reported to be [[leukemia]]. |

|||

[[Image:Julioortazar.JPG|alt=Marble grave stone with mementoes, flowers, notes and other small items placed on it.|thumb|right|240px|Cortazar's grave in Montparnasse, Paris]] |

|||

==Work and legacy== |

==Work and legacy== |

||

| Line 39: | Line 50: | ||

Mentioned and spoken highly of in Rabih Alameddine's novel, '[[Koolaids: The Art of War]]', which was published in 1998. |

Mentioned and spoken highly of in Rabih Alameddine's novel, '[[Koolaids: The Art of War]]', which was published in 1998. |

||

==Notable works== |

|||

*''Presencia'' (1940) |

|||

*''Los reyes'' (1949) |

|||

*''El examen'' (1950, first published in 1985) |

|||

*''[[Bestiario]]'' (1951) |

|||

*''[[Final del juego]]'' (1956) |

|||

*''[[Las armas secretas]]'' (1959) |

|||

*''[[Los premios]]'' (The Winners) (1960) |

|||

*''[[Historias de cronopios y de famas]]'' (1962) |

|||

*''[[Hopscotch (Julio Cortázar novel)|Rayuela]]'' (''Hopscotch'') (1963) |

|||

*''[[Todos los fuegos el fuego]]'' (1966) |

|||

*''[[Blow-up and Other Stories]]'' (1968) |

|||

:<small>Originally published in Spanish as "Ceremonias" (Barcelona, Seix Barral), title by which is widely known in Spanish literary circles, and in English (translated by Paul Blackburn) as ''End of the Game and Other Stories''</small> |

|||

:<small>A compilation of stories translated into English from the books [[Final del juego]] and [[Las armas secretas]]</small> |

|||

*[[Around the Day in Eighty Worlds|''Around the Day in Eighty Worlds<small> (La vuelta al día en ochenta mundos)</small>'' (1967)]] |

|||

*[[62: A Model Kit|''62: A Model Kit<small> (62, modelo para armar)</small>'' (1968)]] |

|||

*[[Último round|''Last Round<small> (Último Round)</small>'' (1969)]] |

|||

*''[[Prosa del Observatorio]]'' (1972) |

|||

*''[[Libro de Manuel]]'' (1973) |

|||

*''[[Octaedro]]'' (1974) |

|||

*''[[Fantomas contra los vampiros multinacionales]]'' (1975) |

|||

*''Alguien anda por ahí'' (1977) |

|||

*''Territorios'' (1978) |

|||

*''[[Un tal Lucas]]'' (1979) |

|||

*''Queremos tanto a Glenda'' (1980) |

|||

*''Deshoras'' (1982) |

|||

*[[Los autonautas de la cosmopista|''Autonauts of the Cosmoroute<small> (Los autonautas de la cosmopista</small>'') (1983)]] |

|||

*''Nicaragua tan violentamente dulce'' (1983) |

|||

*''Divertimento'' (1986) |

|||

*''Diary of Andrés Fava'' <small>(''Diario de Andrés Fava'')</small> (1995) |

|||

*''Adiós Robinson'' (1995) |

|||

*''Save Twilight'' (1997) |

|||

*''Cartas'' (three volumes) (2000) |

|||

*''Papeles inesperados'' (2009) |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 19:48, 9 April 2010

Julio Florencio Cortázar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pen name | Julio Denis |

| Occupation | Writer, translator |

| Genre | Fiction, prose, epic, poetry |

| Literary movement | Latin American Boom |

| Notable works | Hopscotch |

Julio Cortázar, born Jules Florencio Cortázar, (August 26, 1914 – February 12, 1984) was an Argentine author of novels and short stories. He influenced an entire generation of Latin American writers from Mexico to Argentina, and most of his best-known work was written in France, where he established himself in 1951.

Early life

Cortázar was born in Brussels, Belgium on August 26, 1914 a few days after the invasion of Belgium by Germany at the start of World War I. His father, Julio José Cortázar, was the European commercial representative for the family of his wife, María Herminia Descotte, and the couple had arrived in Belgium in 1913.[1] They were both Argentine. As Cortázar himself put it, his "birth was a product of tourism and diplomacy."[2]

Soon after the child's birth the family traveled via Frankfurt to Zürich, where they were reunited with María Herminia's parents: Victoria Gabel, who was a German citizen, and her lover, Descotte, who was a French citizen at a time when Frenchmen were not welcome in Belgium. The family spent two years in Switzerland, spent a short time in Barcelona towards the end of the war, and then returned to Argentina.

By then, however, Julio José Cortázar and María Herminia Descotte had split up.[3] Cortázar spent the rest of his childhood in Banfield, near Buenos Aires, with his mother and his only sister, who was one year younger. He never saw his father again.[citation needed] His childhood home, with its backyard, was a source of inspiration for some of his stories.[citation needed] Despite this, he wrote a letter to Graciela M. de Solá (December 4, 1963) describing this period of his life as "full of servitude, excessive touchiness, terrible and frequent sadness." He was a sickly child and spent much of his childhood in bed reading.[citation needed] His mother selected what he read, introducing her son most notably to the works of Jules Verne, whom Cortázar admired for the rest of his life. In the magazine Plural (issue 44, Mexico City, May 1975) he wrote: "I spent my childhood in a haze full of goblins and elfs, with a sense of space and time that was different from everybody else's."

Education and teaching career

Cortázar became a primary school teacher when he was 18 (at that time, teacher´s degrees in Argentina were a diploma obtained after finishing high school and taking some more courses and exams). Although Cortázar never completed his degree in philosophy and languages at the University of Buenos Aires, he taught in several provincial high schools. In 1938 he published a volume of sonnets under the pseudonym Julio Denis.[citation needed] He later repudiated this volume. In a 1977 interviews for Spanish TV he stated that publishing that book was his only transgression to the principle of not publishing any books until he was convinced that what was written in them was what he meant to say.[citation needed] In 1944 he became professor of French literature at the National University of Cuyo. In 1949 he published a play, Los Reyes (The Kings), based on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur.

Years in France

In 1951, Cortázar, who was opposed to the government of Juan Domingo Perón,[4] emigrated to France, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life. From 1952 onward, he worked for UNESCO as a translator. The projects he worked on included Spanish renderings of Robinson Crusoe, Marguerite Yourcenar's novel Mémoires d'Hadrien, and stories by Edgar Allan Poe. He also came under the influence of the works of Alfred Jarry and the Comte de Lautréamont, and wrote most of his major works in Paris. In later years he became actively engaged in opposing abuses of human rights in Latin America, and was a supporter of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua.

Cortázar was married three times, to Aurora Bernárdez, to Ugnė Karvelis, and finally to Carol Dunlop. He died in Paris in 1984 and is interred in the Cimetière de Montparnasse, next to Carol Dunlop. The cause of his death was reported to be leukemia.

Work and legacy

Cortázar wrote numerous short stories, collected in such volumes as Bestiario (1951), Final del juego (1956), and Las armas secretas (1959). English translations by Paul Blackburn of stories selected from these volumes were published Blow-up and Other Stories (1967). The title of this collection refers to Michelangelo Antonioni's film Blowup (1967), which was inspired by Cortázar's story Las Babas del Diablo (literally, "The Droolings of the Devil"). Puerto Rican novelist Giannina Braschi used Cortázar's story as a springboard for the chapter called "Blow-up" in her bilingual novel "Yo-Yo Boing!" (1998). Another story "La Autopista del Sur" ("The Southern Thruway") influenced another film of the 1960s, Jean-Luc Godard's Week End (1967).[citation needed] Another notable story, "El Perseguidor" ("The Pursuer"),[citation needed] was based on the life of the jazz musician Charlie Parker.

Cortázar also published several novels, including Los premios (The Winners, 1960), Hopscotch (Rayuela, 1963), 62: A Model Kit (62 Modelo para Armar, 1968), and Libro de Manuel (A Manual for Manuel, 1973). These have been translated into English by Gregory Rabassa. The open-ended structure of Hopscotch, which invites the reader to choose between a linear and a non-linear mode of reading, has been praised by other Latin American writers, including José Lezama Lima, Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, and Mario Vargas Llosa. Cortázar's use of interior monologue and stream of consciousness owes much to James Joyce and other modernists, but his main influences were Surrealism, the French Nouveau roman and the improvisatory aesthetic of jazz. Cortázar also mentions Lawrence Durrell's The Alexandria Quartet several times in Hopscotch.[5] His first wife, Aurora Bernárdez, was translating Durrell into Spanish while Cortázar was writing the novel.

Cortázar also published poetry, drama, and various works of non-fiction. He also translated Edgar Allan Poe's 1838 novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket into Spanish as Narracion de Arthur Gordon Pym. One of his last works was a collaboration with his third wife, Carol Dunlop, The Autonauts of the Cosmoroute, which relates, partly in mock-heroic style, the couple's extended expedition along the autoroute from Paris to Marseille in a Volkswagen camper nicknamed Fafner.

In Buenos Aires, a school, a public library, and a square in the neighbourhood of Palermo carry his name. The square is particularly well-known as a centre of a trendy and bohemian area with an important nightlife (sometimes referred to as "Plaza Serrano" or "Palermo Soho")

In 2007 Bertrand Delanoë, the Mayor of Paris, formally named a small square on the Île Saint-Louis in honor of Julio Cortázar.[citation needed]

Duke University Press published a literary journal ) called "Hopscotch: A Cultural Review", named after Cortázar's novel.

Mentioned and spoken highly of in Rabih Alameddine's novel, 'Koolaids: The Art of War', which was published in 1998.

Notable works

- Presencia (1940)

- Los reyes (1949)

- El examen (1950, first published in 1985)

- Bestiario (1951)

- Final del juego (1956)

- Las armas secretas (1959)

- Los premios (The Winners) (1960)

- Historias de cronopios y de famas (1962)

- Rayuela (Hopscotch) (1963)

- Todos los fuegos el fuego (1966)

- Blow-up and Other Stories (1968)

- Originally published in Spanish as "Ceremonias" (Barcelona, Seix Barral), title by which is widely known in Spanish literary circles, and in English (translated by Paul Blackburn) as End of the Game and Other Stories

- A compilation of stories translated into English from the books Final del juego and Las armas secretas

- Around the Day in Eighty Worlds (La vuelta al día en ochenta mundos) (1967)

- 62: A Model Kit (62, modelo para armar) (1968)

- Last Round (Último Round) (1969)

- Prosa del Observatorio (1972)

- Libro de Manuel (1973)

- Octaedro (1974)

- Fantomas contra los vampiros multinacionales (1975)

- Alguien anda por ahí (1977)

- Territorios (1978)

- Un tal Lucas (1979)

- Queremos tanto a Glenda (1980)

- Deshoras (1982)

- Autonauts of the Cosmoroute (Los autonautas de la cosmopista) (1983)

- Nicaragua tan violentamente dulce (1983)

- Divertimento (1986)

- Diary of Andrés Fava (Diario de Andrés Fava) (1995)

- Adiós Robinson (1995)

- Save Twilight (1997)

- Cartas (three volumes) (2000)

- Papeles inesperados (2009)

Further reading

English

- Julio Cortázar (Modern Critical Views) / Bloom, Harold., 2005

- Mothers, lovers, and others : the short stories of Julio Cortázar / Schmidt-Cruz, Cynthia., 2004

- Julio Cortázar (Bloom's Major Short Story Writers) / Bloom, Harold., 2004

- The Lights of Home: A Century of Latin American Writers in Paris / Weiss, Jason., 2002

- Understanding Julio Cortázar / Standish, Peter., 2001

- Questions of the liminal in the fiction of Julio Cortázar / Moran, Dominic., 2000

- Critical essays on Julio Cortázar / Alazraki, Jaime., 1999

- Julio Cortázar : new readings / Alonso, Carlos J., 1998

- Julio Cortázar : a study of the short fiction / Stavans, Ilan., 1996

- The politics of style in the fiction of Balzac, Beckett, and Cortázar / Axelrod, Mark., 1992

- Writing at Risk: Interviews in Paris With Uncommon Writers / Weiss, Jason., 1991

- The contemporary praxis of the fantastic : Borges and Cortázar / Rodríguez-Luis, Julio., 1991

- Julio Cortázar's character mosaic : reading the longer fiction / Yovanovich, Gordana., 1991

- Julio Cortázar (Twayne World Authors Series) / Peavler, Terry., 1990

- Julio Cortázar : life, work and criticism / Carter, E. Dale., 1986

- The novels of Julio Cortázar / Boldy, Steven., 1980

Spanish

- Discurso del Oso / children's book illustrated by Emilio Urberuaga, Libros del Zorro Rojo, 2008

- Imagen de Julio Cortázar / Claudio Eduardo Martyniuk., 2004

- Julio Cortázar desde tres perspectivas / Luisa Valenzuela., 2002

- Otra flor amarilla : antología : homenaje a Julio Cortázar / Universidad de Guadalajara., 2002

- Julio Cortázar / Cristina Peri Rossi., 2001

- Julio Cortázar / Alberto Cousté., 2001

- La mirada recíproca : estudios sobre los últimos cuentos de Julio Cortázar / Peter Fröhlicher., 1995

- Hacia Cortázar : aproximaciones a su obra / Jaime Alazraki., 1994

- Julio Cortázar : mundos y modos / Saúl Yurkiévich., 1994

- Tiempo sagrado y tiempo profano en Borges y Cortázar / Zheyla Henriksen., 1992

- Cortázar : el romántico en su observatorio / Rosario Ferré., 1991

- Lo neofantástico en Julio Cortázar / Julia G Cruz., 1988

- Los Ochenta mundos de Cortázar : ensayos / Fernando Burgos., 1987

- En busca del unicornio : los cuentos de Julio Cortázar / Jaime Alazraki., 1983

- Teoría y práctica del cuento en los relatos de Cortázar / Carmen de Mora Valcárcel., 1982

- Julio Cortázar / Pedro Lastra., 1981

- Cortázar : metafísica y erotismo / Antonio Planells., 1979

- Es Julio Cortázar un surrealista? / Evelyn Picon Garfield., 1975

- Estudios sobre los cuentos de Julio Cortázar / David Lagmanovich., 1975

- Cortázar y Carpentier / Mercedes Rein., 1974

- Los mundos de Julio Cortázar / Malva E Filer., 1970

- Yo y Cortázar / Christina Perri Rossi, 2001

Filmography

- Cortázar, 1994. Documentary directed by Tristán Bauer.

- Cortázar, apuntes para un documental, 2002. Documentary directed by Eduardo Montes-Bradley.

- Graffiti, 2005. Short movie based in Julio Cortázar´s short story "GRAFFITI". Directed by Pako González.[1]

See also

Notes

- ^ Cortázar sin barba, by Eduardo Montes-Bradley. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004

- ^ Televisión Española, Serie A Fondo. Interview by: Joaquin Soler Serrano.

- ^ Cortázar sin barba, by Eduardo Montes-Bradley. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004

- ^ Cortázar sin barba, by Eduardo Montes-Bradley. Random House Mondadori, Editorial Debate, Madrid, 2004

- ^ Sligh, Charles. "Reading the Divergent Weave A Note and Some Speculations on Durrell and Cortázar." [Deus Loci: The Lawrence Durrell Journal] NS 6 (1998): 118-132.

External links

- Lost in Paris with Julio Cortázar and Carol Dunlop

- Julio Cortázar - National and Literary Perspectives

- Julio Cortázar )[2]

- Julio Cortázar Collection (Finding Aid) - Princeton University Library Manuscripts Division [3]

- Julio Cortázar: An Argentinean Master of Anti-novel and Experimental Literature

- Articles needing cleanup from August 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from August 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from August 2008

- 1914 births

- Postmodern literature

- People from Paris

- Postmodernists

- People from Brussels

- Argentines of French descent

- Argentine writers

- Argentine novelists

- Argentine translators

- Argentine short story writers

- University of Buenos Aires alumni

- 1984 deaths