Nez Perce

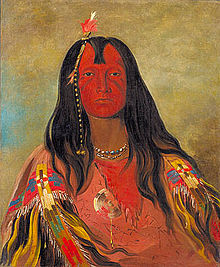

No Horn on His Head, a Nez Perce man painted by George Catlin | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,499[1] (2010 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Idaho) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Nez Perce | |

| Religion | |

| Seven Drum (Walasat), Christianity, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Sahaptin peoples |

The Nez Perce (/ˌnɛzˈpɜːrs/; autonym: Niimíipuu, meaning "the walking people" or "we, the people")[2] are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States for a long[quantify] time.[3]

Members of the Sahaptin language group,[4] the Niimíipuu were the dominant people of the Columbia Plateau for much of that time,[5] especially after acquiring the horses that led them to breed the appaloosa horse in the 18th century.

Prior to "first contact" with Western civilization the Nimiipuu were economically and culturally influential in trade and war, interacting with other indigenous nations in a vast network from the western shores of Oregon and Washington, the high plains of Montana, and the northern Great Basin in southern Idaho and northern Nevada.[6][7]

After first contact, the name "Nez Perce" was given to the Niimíipuu and the nearby Chinook people by French explorers and trappers. The name means "pierced nose," but only the Chinook used that form of decoration.[8]

Today they are a federally recognized tribe, the Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho, and govern their Indian reservation in Idaho through a central government headquartered in Lapwai, Idaho known as the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee (NPTEC).[9][10] They are one of five federally recognized tribes in the state of Idaho. Some still speak their traditional language, and the Tribe owns and operates two casinos along the Clearwater River in Idaho in Kamiah, Idaho and outside of Lewiston, Idaho, health clinics, a police force and court, community centers, salmon fisheries, radio station, and other things that promote economic and cultural self-determination.[11]

Cut off from most of their horticultural sites throughout the Camas Prairie[3] by an 1863 treaty,[8] confinement to reservations in Idaho, Washington and Oklahoma Indian Territory after the Nez Perce War of 1877, and Dawes Act of 1887 land allotments (today some Nez Perce lease land to farmers or loggers, but the Nez Perce only own 12% of their own reservation),[12] the Nez Perce remain as a distinct culture and political economic influence within and outside their reservation.[13][14][15][16] Today, hatching, harvesting and eating salmon is an important cultural and economic strength of the Nez Perce through full ownership or co-management of various salmon fish hatcheries, such as the Kooskia National Fish Hatchery in Kooskia, Idaho or the Dworshak National Fish Hatchery in Orofino, Idaho.[17][18][19]

Nez Perce tribe information

Their name for themselves is Nimíipuu (pronounced [nimiːpuː]), meaning, "The People", in their language, part of the Sahaptin family.[20]

Nez Percé is an exonym given by French Canadian fur traders who visited the area regularly in the late 18th century, meaning literally "pierced nose." English-speaking traders and settlers adopted the name in turn. Since the late 20th century, the Nez Perce identify most often as Niimíipuu in Sahaptin.[20] The Lakota/ Dakota named them the Watopala, or Canoe people, from Watopa. However, after Nez Perce became a more common name, they changed it to Watopahlute. This comes from pahlute, nasal passage & is simply a play on words. If translated literally, it would come out as either "Nasal Passage of the Canoe," (Watopa-pahlute) or "Nasal Passage of the Grass." (Wato-pahlute)[21] The tribe also uses the term "Nez Perce," as does the United States Government in its official dealings with them, and contemporary historians. Older historical ethnological works and documents use the French spelling of Nez Percé, with the diacritic. The original French pronunciation is [ne pɛʁse], with three syllables.

The interpreter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition mistakenly identified this people as the Nez Perce when the team encountered the tribe in 1805. Writing in 1889, anthropologist Alice Fletcher, who the U.S. government had sent to Idaho to allot the Nez Perce Reservation, explained the mistaken naming. She wrote, "It is never easy to come at the name of an Indian or even of an Indian tribe. A tribe has always at least two names; one they call themselves by and one by which they are known to other tribes. All the tribes living west of the Rocky Mountains were called "Chupnit-pa-lu," which means people of the pierced noses; it also means emerging from the bushes or forest; the people from the woods. The tribes on the Columbia river used to pierce the nose and wear in it some ornament as you have seen some old fashioned white ladies wear in their ears. Lewis and Clark had with them an interpreter whose wife was a Shoshone or Snake woman and so it came about that when it was asked "What Indians are these?" the answer was "They are 'Chupnit-pa-lu'" and it was written down in the journal; spelled rather queerly, for white people's ears do not always catch Indian tones and of course the Indians could not spell any word."[22]

In his journals, William Clark referred to the people as the Chopunnish /ˈtʃoʊpənɪʃ/, a transliteration of a Sahaptin term. According to D.E. Walker in 1998, writing for the Smithsonian, this term is an adaptation of the term cú·pʼnitpeľu (the Nez Perce people). The term is formed from cú·pʼnit (piercing with a pointed object) and peľu (people).[23] By contrast, the Nez Perce Language Dictionary[24] has a different analysis than did Walker for the term cúpnitpelu. The prefix cú- means "in single file." This prefix, combined with the verb -piní, "to come out (e.g. of forest, bushes, ice)". Finally, with the suffix of -pelú, meaning "people or inhabitants of." Together, these three elements: cú- + -piní + pelú = cúpnitpelu, or "the People Walking Single File Out of the Forest."[25] Nez Perce oral tradition indicates the name "Cuupn'itpel'uu" meant "we walked out of the woods or walked out of the mountains" and referred to the time before the Nez Perce had horses.[26]

Language

The Nez Perce language, or Niimiipuutímt, is a Sahaptian language related to the several dialects of Sahaptin. The Sahaptian sub-family is one of the branches of the Plateau Penutian family, which in turn may be related to a larger Penutian grouping.

Aboriginal territory

The Nez Perce territory at the time of Lewis and Clark (1804–1806) was approximately 17,000,000 acres (69,000 km2) and covered parts of present-day Washington, Oregon, Montana, and Idaho, in an area surrounding the Snake (Weyikespe), Grande Ronde River, Salmon (Naco’x kuus) ("Chinook salmon Water") and the Clearwater (Koos-Kai-Kai) ("Clear Water") rivers. The tribal area extended from the Bitterroots in the east (the door to the Northwestern Plains of Montana) to the Blue Mountains in the west between latitudes 45°N and 47°N.[27]

In 1800, the Nez Perce had more than 100 permanent villages, ranging from 50 to 600 individuals, depending on the season and social grouping. Archeologists have identified a total of about 300 related sites including camps and villages, mostly in the Salmon River Canyon. In 1805, the Nez Perce were the largest tribe on the Columbia River Plateau, with a population of about 6,000. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Nez Perce had declined to about 1,800 due to epidemics, conflicts with non-Indians, and other factors.[28] A total of 3,499 Nez Perce were counted in the 2010 Census.[1]

Like other Plateau tribes, the Nez Perce had seasonal villages and camps in order to take advantage of natural resources throughout the year. Their migration followed a recurring pattern from permanent winter villages through several temporary camps, nearly always returning to the same locations each year. The Nez Perce traveled via the Lolo Trail (Salish: Naptnišaqs - "Nez Perce Trail") (Khoo-say-ne-ise-kit) far east as the Plains (Khoo-sayn / Kuseyn) ("Buffalo country") of Montana to hunt buffalo (Qoq'a lx) and as far west as the Pacific Coast (’Eteyekuus) ("Big Water"). Before 1957 construction of The Dalles Dam, which flooded this area, Celilo Falls (Silayloo) was a favored location on the Columbia River (Xuyelp) ("The Great River") for salmon (lé'wliks)-fishing.

Enemies and Allies

The Nez Perce had many allies and trading partners among neighboring peoples, but also enemies and ongoing antagonist tribes. To the north of them lived the Coeur d’Alene (Schitsu'umsh) (’Iskíicu’mix), Spokane (Sqeliz) (Heyéeynimuu), and further north the Kalispel (Ql̓ispé) (Qem’éespel’uu, both meaning "Camas People"), Colville (Páapspaloo) and Kootenay / Kootenai (Ktunaxa) (Kuuspel’úu), to the northwest lived the Palus (Pelúucpuu) and to the west the Cayuse (Lik-si-yu) (Weyíiletpuu - "Ryegrass People"), west bound there were found the Umatilla (Imatalamłáma) (Hiyówatalampoo), Walla Walla, Wasco (Wecq’úupuu) and Sk'in (Tike’éspel’uu) and northwest of the latter various Yakama bands (Lexéyuu), to the south lived the Snake Indians (various Northern Paiute (Numu) bands (Hey’ǘuxcpel’uu) in the southwest and Bannock (Nimi Pan a'kwati)-Northern Shoshone (Newe) bands[29] (Tiwélqe) in the southeast), to the east lived the Lemhi Shoshone (Lémhaay), north of them the Bitterroot Salish / Flathead (Seliš) (Séelix), further east and northeast on the Northern Plains were the Crow (Apsáalooke) (’Isúuxe) and two powerful alliances - the Iron Confedery (Nehiyaw-Pwat) (named after the dominating Plains and Woods Cree (Paskwāwiyiniwak and Sakāwithiniwak) and Assiniboine (Nakoda) (Wihnen’íipel’uu), an alliance of northern plains Indian nations based around the fur trade, and later included the Stoney (Nakoda), Western Saulteaux / Plains Ojibwe (Bungi or Nakawē), and Métis) and the Blackfoot Confederacy (Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi) (’Isq’óyxnix) (composed of three Blackfoot speaking peoples - the Piegan or Peigan (Piikáni), the Kainai or Bloods (Káínaa), and the Siksika or Blackfoot (Siksikáwa), later joined by the unrelated Sarcee (Tsuu T'ina) and (for a time) by Gros Ventre or Atsina (A'aninin)).[30]

Historic bands

- Almotipu Band

- Alpowna (Alpowai) Band or Alpowe'ma (Alpoweyma/Alpowamino) Band ("People along Alpaha (Alpowa) Creek" or "People of ’Al’pawawaii, i.e. Clarkston")

- Assuti Band ("People along Assuti Creek")

- Atskaaiwawipu Band or Asahkaiowaipu Band ("People at the confluence, People from the river mouth, i.e. Ahsahka")

- Hatweme (Hatwēme) Band or Hatwai (Héetwey) Band ("People along Hatweh Creek")

- Hinsepu Band

- Kămiăhpu Band or Kimmooenim Band ("People of Kămiăhp", "People of the Many Rope Litters Place, i.e. Kamiah")

- Kannah Band or Kam'nakka Band ("People along Clearwater River")

- Lamtáma (Lamátta) Band or Lamatama Band ("People of a region with little snow, i.e. Lamtáma (Lamátta) region"), also called Salmon River Band

- Lapwai Band or Lapwēme Band ("People of the Butterfly Place, i.e. Lapwai")

- Mákapu Band ("People from Máka/Maaqa along Cottonwood Creek (formerly: Maka Creek")

- Pikunan (Pikunin) Band or Pikhininmu Band ("Snake River People"), also called Snake River tribe

- Saiksaikinpu Band

- Saxsano Band

- Taksehepu Band ("People of Tukeespe/Tu-kehs-pa APS, i.e. Ghost town Agatha")

- Tukpame Band

- Wallowa (Willewah) Band or Walwáma (Walwáama) Band ("People along the Wallowa River" or "People along the Grand Ronde River"), also known as Kămúinnu Band or Qéemuynu Band ("People of the Indian Hemp")[31][32][33]

- Yakama Band or Yăkámă Band ("People of the Yăká River, i.e. Potlatch River (above its mouth into the Clearwater River)", not to confused with the Yakama peoples)[34]

Because of great inter-marriage between Nez Perce bands and neighboring tribes or bands to forge alliances and peace (often living in mixed bilingual villages together), the following bands were also counted to the Nez Perce (which today are viewed as being linguistically and culturally closely related, but separate ethnic groups):

- Walla Walla Band

- These were the Walla Walla people which lived along the Walla Walla River and along the confluence of the Snake and Columbia River rivers, today they are enrolled in the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

- Pelloatpallah Band or Palous Band

- These were the Palus (or Palus proper) Band and Wawawai Band of the Upper Palus Band - which constituted together with the Middle Palus Band und Lower Palus Band - one of the three main groups of the Palus people, which lived along the Columbia, Snake and Palouse Rivers to the northwest of the Nez Perce. Today the majority is enrolled in the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and some are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation.

- Weyiiletpuu (Wailetpu) Band or Yeletpo Band

- These were the Cayuse people which lived to the west of the Nez Perce at the headwaters of the Walla Walla, Umatilla and Grande Ronde River and from the Blue Mountains westwards up to the Deschutes River, they oft shared village sites with the Nez Perce and Palus and were feared by neighboring tribes, as early as 1805, most Cayuse had given up their mother tongue and had switched to Weyíiletpuu, a variety of the Lower Nez Perce/Lower Niimiipuutímt dialect of the Nez Perce language. They called themselves by their Nez-Percé name as Weyiiletpuu ("Ryegrass People"); today most Cayuse are enrolled into the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, some as Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs or Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho.

Culture

The semi-sedentary Nez Percés were Hunter-gatherer without agriculture living in a society in which most or all food is obtained by foraging (collecting wild plants and roots and pursuing wild animals). They depended on hunting, fishing, and the gathering of wild roots and berries.

Nez Perce people historically depended on various Pacific salmon and Pacific trout for their food: Chinook salmon or "nacoox" (Oncorhynchus tschawytscha) were eaten the most, but other species such as Pacific lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus or Lampetra tridentata), and chiselmouth.[35] Other important fishes included the Sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), Silver salmon or ka'llay (Oncorhynchus kisutch), Chum salmon or dog salmon or ka'llay (Oncorhynchus keta), Mountain whitefish or "ci'mey" (Prosopium williamsoni), White sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus), White sucker or "mu'quc" (Catostomus commersonii), and varieties of trout - West Coast steelhead or "heyey" (Oncorhynchus mykiss), brook trout or "pi'ckatyo" (Salvelinus fontinalis), bull trout or "i'slam" (Salvelinus confluentus), and Cutthroat trout or "wawa'lam" (Oncorhynchus clarkii).[36]

Prior to contact with Europeans, the Nez Perce's traditional hunting and fishing areas spanned from the Cascade Range in the west to the Bitterroot Mountains in the east.[37]

Historically, in late May and early June, Nez Perce villagers crowded to communal fishing sites to trap eels, steelhead, and chinook salmon, or haul in fish with large dip nets. Fishing took place throughout the summer and fall, first on the lower streams and then on the higher tributaries, and catches also included salmon, sturgeon, whitefish, suckers, and varieties of trout. Most of the supplies for winter use came from a second run in the fall, when large numbers of Sockeye salmon, silver, and dog salmon appeared in the rivers.

Fishing is traditionally an important ceremonial and commercial activity for the Nez Perce tribe. Today Nez Perce fishers participate in tribal fisheries in the mainstream Columbia River between Bonneville and McNary dams. The Nez Perce also fish for spring and summer Chinook salmon and Rainbow trout/steelhead in the Snake River and its tributaries. The Nez Perce tribe runs the Nez Perce Tribal Hatchery on the Clearwater River, as well as several satellite hatchery programs.

The first fishing of the season was accompanied by prescribed rituals and a ceremonial feast known as "kooyit". Thanksgiving was offered to the Creator and to the fish for having returned and given themselves to the people as food. In this way, it was hoped that the fish would return the next year.

Like salmon, plants contributed to traditional Nez Perce culture in both material and spiritual dimensions.[38]

Aside from fish and game, Plant foods provided over half of the dietary calories, with winter survival depending largely on dried roots, especially Kouse, or "qáamsit" (when fresh) and "qáaws" (when peeled and dried) (Lomatium especially Lomatium cous), and Camas, or "qém'es" (Nez Perce: "sweet") (Camassia quamash), the first being roasted in pits, while the other was ground in mortars and molded into cakes for future use, both plants had been traditionally an important food and trade item.[38] Women were primarily responsible for the gathering and preparing of these root crops. Camas bulbs were gathered in the region between the Salmon and Clearwater river drainages.[39] Techniques for preparing and storing winter foods enabled people to survive times of colder winters with little or no fresh foods.[38]

Favorite fruits dried for winter were serviceberries or "kel" (Amelanchier alnifolia or Saskatoon berry), black huckleberries or "cemi'tk" (Vaccinium membranaceum), red elderberries or "mi'ttip" (Sambucus racemosa var. melanocarpa), and chokecherries or "ti'ms" (Prunus virginiana var. melanocarpa). Nez Perce textiles were made primarily from dogbane or "qeemu" (Apocynum cannabinum or Indian hemp), tules or "to'ko" (Schoenoplectus acutus var. acutus), and western redcedar or "tala'tat" (Thuja plicata). The most important industrial woods were redcedar, ponderosa pine or "la'qa" (Pinus ponderosa), Douglas fir or "pa'ps" (Pseudotsuga menziesii), sandbar willow or "tax's" (Salix exigua), and hard woods such as Pacific yew or "ta'mqay" (Taxus brevifolia) and syringa or "sise'qiy" (Philadelphus lewisii or Indian arrowwood).[38]

Many fishes and plants important to Nez Perce culture are today state symbols: the black huckleberry or "cemi'tk" is the official state fruit and the Indian arrowwood or "sise'qiy", the Douglas fir or "pa'ps" is the state tree of Oregon and the ponderosa pine or "la'qa" of Montana, the Chinook salmon is the state fish of Oregon, the cutthroat trout or "wawa'lam" of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, and the West Coast steelhead or "heyey" of Washington.

The Nez Perce believed in spirits called weyekins (Wie-a-kins) which would, they thought, offer a link to the invisible world of spiritual power".[40] The weyekin would protect one from harm and become a personal guardian spirit. To receive a weyekin, a seeker would go to the mountains alone on a vision quest. This included fasting and meditation over several days. While on the quest, the individual may receive a vision of a spirit, which would take the form of a mammal or bird. This vision could appear physically or in a dream or trance. The weyekin was to bestow the animal's powers on its bearer—for example; a deer might give its bearer swiftness. A person's weyekin was very personal. It was rarely shared with anyone and was contemplated in private. The weyekin stayed with the person until death.

Helen Hunt Jackson, author of "A Century of Dishonor", written in 1889 refers to the Nez Perce as "the richest, noblest, and most gentle" of Indian peoples as well as the most industrious.[41]

The museum at the Nez Perce National Historical Park, headquartered in Spalding, Idaho, and managed by the National Park Service includes a research center, archives, and library. Historical records are available for on-site study and interpretation of Nez Perce history and culture.[42] The park includes 38 sites associated with the Nez Perce in the states of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Washington, many of which are managed by local and state agencies.[42]

History

European contact

In 1805 William Clark was the first known Euro-American to meet any of the tribe, excluding the aforementioned French Canadian traders. While he, Meriwether Lewis and their men were crossing the Bitterroot Mountains, they ran low of food, and Clark took six hunters and hurried ahead to hunt. On September 20, 1805, near the western end of the Lolo Trail, he found a small camp at the edge of the camas-digging ground, which is now called Weippe Prairie. The explorers were favorably impressed by the Nez Perce whom they met. Preparing to make the remainder of their journey to the Pacific by boats on rivers, they entrusted the keeping of their horses until they returned to "2 brothers and one son of one of the Chiefs." One of these Indians was Walammottinin (meaning "Hair Bunched and tied," but more commonly known as Twisted Hair). He was the father of Chief Lawyer, who by 1877 was a prominent member of the "Treaty" faction of the tribe. The Nez Perce were generally faithful to the trust; the party recovered their horses without serious difficulty when they returned.[43]

Recollecting the Nez Perce encounter with the Lewis and Clark party, in 1889 anthropologist Alice Fletcher wrote that "the Lewis and Clark explorers were the first white men that many of the people had ever seen and the women thought them beautiful." She wrote that the Nez Perce "were kind to the tired and hungry party. They furnished fresh horses and dried meat and fish with wild potatoes and other roots which were good to eat, and the refreshed white men went further on, westward, leaving their bony, wornout horses for the Indians to take care of and have fat and strong when Lewis and Clark should come back on their way home." On their return trip they arrived at the Nez Perce encampment the following spring, again hungry and exhausted. The tribe constructed a large tent for them and again fed them. Desiring fresh red meat, the party offered an exchange for a Nez Perce horse. Quoting from the Lewis and Clark diary, Fletcher writes, "The hospitality of the Chiefs was offended at the idea of an exchange. He observed that his people had an abundance of young horses and that if we were disposed to use that food, we might have as many as we wanted." The party stayed with the Nez Perce for a month before moving on.[44]

Fight of the Nez Perce

The Nez Perce were one of the tribal nations at the Walla Walla Council (1855) (along with the Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Yakama), which signed the Treaty of Walla Walla.[45]

Under pressure from the European Americans, in the late 19th century the Nez Perce split into two groups: one side accepted the coerced relocation to a reservation and the other refused to give up their fertile land in Idaho and Oregon. Those willing to go to a reservation made a treaty in 1877. The flight of the non-treaty Nez Perce began on June 15, 1877, with Chief Joseph, Looking Glass, White Bird, Ollokot, Lean Elk (Poker Joe) and Toohoolhoolzote leading 2,900 men, women and children in an attempt to reach a peaceful sanctuary. They intended to seek shelter with their allies the Crow but, upon the Crow's refusal to offer help, the Nez Perce tried to reach the camp in Canada of Lakota Chief Sitting Bull. He had migrated there instead of surrendering after the decisive Indian victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Nez Perce were pursued by over 2,000 soldiers of the U.S. Army on an epic flight to freedom of more than 1,170 miles (1,880 km) across four states and multiple mountain ranges. The 800 Nez Perce warriors defeated or held off the pursuing troops in 18 battles, skirmishes, and engagements. More than 300 US soldiers and 1,000 Nez Perce (including women and children) were killed in these conflicts.[46]

A majority of the surviving Nez Perce were finally forced to surrender on October 5, 1877, after the Battle of the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana, 40 miles (64 km) from the Canada–US border. Chief Joseph surrendered to General Oliver O. Howard of the U.S. Cavalry.[47] During the surrender negotiations, Chief Joseph sent a message, usually described as a speech, to the US soldiers. It has become renowned as one of the greatest American speeches: "...Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."[48]

The route of the Nez Perce flight is preserved by the Nez Perce National Historic Trail.[49] The annual Cypress Hills ride in June commemorates the Nez Perce people's attempt to escape to Canada.[50]

Nez Perce horse breeding program

on horse, 1910

In 1994 the Nez Perce tribe began a breeding program, based on crossbreeding the Appaloosa and a Central Asian breed called Akhal-Teke, to produce what they called the Nez Perce Horse.[51] They wanted to restore part of their traditional horse culture, where they had conducted selective breeding of their horses, long considered a marker of wealth and status, and trained their members in a high quality of horsemanship. Social disruption due to reservation life and assimilationist pressures by Americans and the government resulted in the destruction of their horse culture in the 19th century. The 20th-century breeding program was financed by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the Nez Perce tribe, and the nonprofit called the First Nations Development Institute. It has promoted businesses in Native American country that reflect values and traditions of the peoples. The Nez Perce Horse breed is noted for its speed.

Nez Perce Indian Reservation

The current tribal lands consist of a reservation in north central Idaho at 46°18′N 116°24′W / 46.300°N 116.400°W, primarily in the Camas Prairie region south of the Clearwater River, in parts of four counties.[52] In descending order of surface area, the counties are Nez Perce, Lewis, Idaho, and Clearwater. The total land area is about 1,195 square miles (3,100 km2), and the reservation's population at the 2000 census was 17,959.[53]

Due to tribal loss of lands, the population on the reservation is predominantly white, nearly 90% in 1988.[54] The largest community is the city of Orofino, near its northeast corner. Lapwai is the seat of tribal government, and it has the highest percentage of Nez Percé people as residents, at about 81.4 percent.

Similar to the opening of Native American lands in Oklahoma by allowing acquisition of surplus by non-natives after households received plots, the U.S. government opened the Nez Percé reservation for general settlement on November 18, 1895. The proclamation had been signed less than two weeks earlier by President Grover Cleveland.[55] Thousands rushed to grab land on the reservation, staking out their claims even on land owned by Nez Percé families.[56][57][58]

Communities

|

|

In addition, the Colville Indian Reservation in eastern Washington contains the Joseph band of Nez Percé.

Notable Nez Perce

- Chief Lawyer (Hallalhotsoot, Halalhot'suut) (c. 1796–1876), son of a Salish-speaking Flathead woman and Twisted Hair, the Nez Perce who welcomed and befriended the exhausted Lewis and Clark Expedition in the September 1805. His father's positive experiences with the whites greatly influenced him, leader of the treaty faction of the Nez Percé, and signed the 1855 Walla Walla Treaty and controversial 1863 treaty.[59] He was called the Lawyer by fur trappers because of his oratory and ability to speak several languages. He defended the actions of the 1863 Treaty which cost the Nez Perce nearly 90% of their lands after gold was discovered because he knew it was futile to resist the US government and its military power. He tried to negotiate the best outcome which still allowed the majority of Nez Perce to live in their usual village locations. He died, frustrated that the U.S. government failed to follow through on the promises made in both treaties, even making a trip to Washington, D.C. to express his frustration.[59] He is buried at the Nikesa Cemetery at the Presbyterian church in Kamiah.[59][60]

- Old Chief Joseph (Tuekakas), (also: tiwíiteq'is) (c. 1785–1871), was leader of the Wallowa Band and one of the first Nez Percé converts to Christianity and vigorous advocate of the tribe's early peace with whites, father of Chief Joseph (also known as Young Joseph).

- Ellis (c. 1810–1848) was the first united leader of the Nez Perce. He was the grandson of the leader Hohots Ilppilp (also known as Red Grizzly Bear), who met with Lewis and Clark.

- Chief Joseph (hinmatóoyalahtq'it - "Thunder traveling to higher areas") (1840–1904), the best-known leader of the Nez Perce, who led his people in their struggle to retain their identity, with about 60 warriors, he commanded the greatest following of the non-treaty chiefs. (also known as Young Joseph)

- Ollokot, (’álok'at, also known as Ollikut) (1840s–1877), younger brother of Chief Joseph, war chief of the Wallowa band, was killed while fighting at the final battle on Snake Creek, near the Bear Paw Mountains on October 4, 1877.

- Looking Glass (younger) or ’Eelelimyeteqenin’ (also: Allalimya Takanin - "Wrapped in the wind") (c. 1832–1877), leader of the non-treaty Alpowai band and war leader, who was killed during the tribe's final battle with the US Army; his following was third and did not exceed 40 men.

- Eagle from the Light,[61] (Tipiyelehne Ka Awpo) chief of the non-treaty Lam'tama band, that traveled east over the Bitterroot Mountains along with Looking Glass' band to hunt buffalo, was present at the Walla Walla Council in 1855 and supported the non-treaty faction at the Lapwai Council, refused to sign the Treaty of 1855 and 1866, left his territory on Salmon River (two miles south of Corvallis) in 1875 with part of his band, and did settle down in Weiser County (Montana), joined with Shoshone Chief's Eagle's Eye. The leadership of the other Lam'tama that rested on the Salmon River was taken by old chief White Bird. Eagle From the Light didn't participate in the War of 1877 because he was too far away.

- Peo Peo Tholekt (piyopyóot’alikt - "Bird Alighting"), a Nez Perce warrior who fought with distinction in every battle of the Nez Perce War, wounded in the Battle of Camas Creek.

- White Bird or Piyóopiyo x̣ayx̣áyx̣ (also: Peo-peo-hix-hiix or Peo peo Hih Hih; more correctly Peopeo Kiskiok Hihih - "White Goose") (d.1892), also referred to as White Pelican was war leader and tooat (Medicine man (or Shaman) or Prophet) of the non-treaty Lamátta or Lamtáama band, belonging to Lahmatta ("area with little snow"), by which White Bird Canyon was known to the Nez Perce, his following was second in size to Joseph's, and did not exceed 50 men

- Toohoolhoolzote, was leader and tooat (medicine man (or shaman) or prophet) of the non-treaty Pikunan band; fought in the Nez Perce War after first advocating peace; died at the Battle of Bear Paw

- Yellow Wolf or Hiímiin maqs maqs / Himíin maqsmáqs (also: He–Mene Mox Mox or Hemene Moxmox, wished to be called Heinmot Hihhih or In-mat-hia-hia - "White Lightning", c. 1855, died August 1935) was a Nez Perce warrior of the non-treaty Wallowa band who fought in the Nez Perce War of 1877, gunshot wound, left arm near wrist; under left eye in the Battle of the Clearwater

- Yellow Bull or Cúuɫim maqsmáqs (also: Chuslum Moxmox), war leader of a non-treaty band

- Wrapped in the Wind (’elelímyeté'qenin’/ háatyata'qanin)

- Rainbow (Wahchumyus), war leader of a non-treaty band, killed in the Battle of the Big Hole

- Five Wounds (Pahkatos Owyeen), wounded in right hand at the Battle of the Clearwater and killed in the Battle of the Big Hole

- Red Owl (Koolkool Snehee), war leader of a non-treaty band

- Poker Joe, warrior and subchief; chosen trail boss and guide of the Nez Percé people following the Battle of the Big Hole, killed in the Battle of Bear Paw; half French Canadian and Nez Perce descent

- Timothy (Tamootsin, 1808–1891), leader of the treaty faction of the Alpowai (or Alpowa) band of the Nez Percé, was the first Christian convert among the Nez Percé, was married to Tamer, a sister of Old Chief Joseph, who was baptized on the same day as Timothy.[62]

- Archie Phinney (1904–1949), scholar and administrator who studied under Franz Boas at Columbia University and produced Nez Perce Texts, a published collection of Nez Perce myths and legends from the oral tradition[63]

- Elaine Miles, actress best known from her role in television's Northern Exposure

- Jack and Al Hoxie, silent film actors; mother was Nez Perce

- Jackson Sundown, war veteran and rodeo champion

- Claudia Kauffman, a former state senator in Washington state

- Bill Pearl, Mr. America and five-time Mr. Universe

-

Chief Lawyer, c. 1861

-

Peo Peo Tholekt (Bird Alighting), a Nez Perce warrior who helped capture the mountain howitzer at the Battle of the Big Hole

-

Yellow Wolf, December 30, 1909

Footnotes

- ^ a b 2010 Figures for total Nez Perce community. Retrieved 2010.10.05

- ^ Aoki, Haruo. 1994. Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ a b Ames, Kenneth and Alan Marshall. 1980. "Villages, Demography and Subsistence Intensification on the Southern Columbia Plateau". North American Archeologist, 2(1): 25-52."

- ^ Map: Distribution of North American Plateau Indians

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Nez Perce People

- ^ Hunn, Eugene and James Selam. 2001. Nch’i-wána, 'the Big River': Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 4.

- ^ "Stern, Theodore. 1998. 'Colombia River Trade Network,' Pp. 641-652 in Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 12, Plateau. Deward E. Walker, Jr., Volume Editor. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution."

- ^ a b Slickpoo, Allen P., Sr. 1973. Noon Nee-Me-Poo (We, The Nez Perces): Culture and History of the Nez Perces, Vol. 1. Lewiston, Idaho: The Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho.

- ^ Nez Perce Tribe official website

- ^ R. David Edmunds "The Nez Perce Flight for Justice," American Heritage, Fall 2008.

- ^ "Official Home of the Nez Perce Tribal Web Site". www.nezperce.org. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ^ Map: Shrinkage of the Nez Perce lands after 1855

- ^ Colombi, Benedict. 2005. "Dammed in Region Six: The Nez Perce Tribe, Agricultural Development, and the Inequality of Scale". American Indian Quarterly, 29(3&4): 560-589.

- ^ Colombi, Benedict. 2012. "Salmon and the Adaptive Capacity of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) Culture to Cope with Change". American Indian Quarterly, 36(1): 75-97."

- ^ Colombi, Benedict. 2012. "The Economics of Dam Building: Nez Perce Tribe and Global-Scale Development". American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 36(1): 123-149.

- ^ Hormel, Leontina M. 2016. "Nez Perce Defending Treaty Lands in Northern Idaho". Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice, 28(1): 76-83.

- ^ Nez Perce Tribe Department of Fisheries & Resources Management

- ^ Landeen, Dan and Allen Pinkham. 1999. Salmon and His People: Fish and Fishing in Nez Perce Culture. Winchester, Idaho: Confluence Press.

- ^ "Nez Perce Tribe, The. 2003. Treaties: Nez Perce Perspectives. The Nez Perce Tribe Environmental Restoration & Waste Management Program, in association with, The United States Department of Energy. Lewiston, ID: Confluence Press."

- ^ a b Aoki, Haruo. Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-520-09763-6.

- ^ Buechel, Eugene & Manhart S.J., Paul "Lakota Dictionary: Lakota-English / English-Lakota, New Comprehensive Edition" 2002.

- ^ "Selections from WITH THE NEZ PERCES Alice Fletcher in the Field, 1889-92 by E. Jane Gay". PBS. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Deward (1998). Plateau. Handbook of North American Indians v. 12. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 437–438. ISBN 0-16-049514-8.

- ^ University of California Press, 1994

- ^ Aoki, Haruo (1994). Nez Perce Dictionary. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 52, 527, 542. ISBN 978-0-520-09763-6.

- ^ "Since Time Immemorial". Lewis & Clark Rediscovery Project. Nez Perce Tribe. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Spinden, Herbert Joseph (1908). Nez Percé Indians. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, v.2 pt.3. American Anthropological Association. p. 172. OCLC 4760170.

- ^ Walker, Jr., Deward E.; Jones, Peter N. (1964). he Nez Perce. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- ^ Paiute-speakers (i.e. Bannocks) called themselves Pan a'kwati/Panákwate - ″on the water side or on the west side″ and their Shoshone kin within the mixed Bannock-Shoshone bands as Wihínakwate - ″on the knife side or on the iron side″ (the equivalent Shoshone words are WihiN'naite and Bannaite)

- ^ "Nimipuutímt Volume 3 Names of Tribes" (PDF).

- ^ Wallowa Valley, Oregon, to Kooskia, Idaho - Discover the Nez Perce Trail (PDF)

- ^ Thomas E. Churchill: Inner Bark Utilization: A Nez Perce Example. (PDF) Oregon State University, Commencement June 1984

- ^ "Home - Nez Perce Wallowa Homeland". www.wallowanezperce.org.

- ^ The North American Indian. Volume 8 - The Nez Perces. Wallawalla. Umatilla. Cayuse. The Chinookan tries. Classic Books Company. ISBN 978-0-7426-9808-6, page 158 - 160 (Source for regional bands, bands and villages)

- ^ Landeen, Dan; Pinkham, Allen (1999). Salmon and His People: Fish & Fishing in Nez Perce Culture. Lewiston, Idaho: Confluence Press. p. 1. ISBN 1881090329. OCLC 41433913.

- ^ Nez Perce National Historical Park (Source for Nez Perce names for Fishes, Animals and Plants

- ^ Landeen (1999), Salmon and His People, p. 92

- ^ a b c d "Plants - Nez Perce National Historical Park". U.S. National Park Service.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Kephart, Susan. "Camas". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick E.; Nelson, Jay T. (2007). Lewis & Clark and the Indian Country: the Native American Perspective. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0252074858. OCLC 132681406.

- ^ Jackson, Helen Hunt (2001-01-01). A Century of Dishonor. Digital Scanning Inc. ISBN 9781582182896.

- ^ a b "Research Center". Nez Perce National Historic Park. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ Josephy, Alvin (1971). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01494-5.

- ^ "Selections from WITH THE NEZ PERCES Alice Fletcher in the Field, 1889–92 by E. Jane Gay". PBS. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Trafzer, Clifford E. (Fall 2005). "Legacy of the Walla Walla Council, 1955". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 106 (3): 398–411. ISSN 0030-4727. Archived from the original on 2007-01-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. The Nez Perce and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965, pp. 632–633.

- ^ "Letters and Quotations of the Nez Perce Flight". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ "Chief Joseph Surrenders". Great Speeches. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ "Maps of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ Praharenka, Gail; Niemeyer, Bernice. "Nez Perce Ride to Freedom". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- ^ "Nez Perce horse culture resurrected through new breed". Idaho Natives. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ "The Nez Perce Reservation with a Map Insert of Idaho" (PDF). Nez Perce Tribe. Geographic Information Systems. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ "Nez Perce Reservation Census of Population". United States Census Bureau. 2000. Archived from the original on July 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Popkey, Dan (October 29, 1988). "Nez Perce Tribe battling whites over economics". Idahonian. Moscow. Associated Press. p. 10A.

- ^ Hamilton, Ladd (June 25, 1961). "Heads were popping up all over the place". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. p. 14.

- ^ Brammer, Rhonda (July 24, 1977). "Unruly mobs dashed to grab land when reservation opened". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. p. 6E.

- ^ "3,000 took part in "sneak" when Nez Perce Reservation was opened". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. November 19, 1931. p. 3.

- ^ "Nez Perce Reservation". Spokesman-Review. December 11, 1921. p. 5.

- ^ a b c Ruark, Janice (February 23, 1977). "Lawyer led Nez Perce in peace before war". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. p. 3.

- ^ "Chief Lawyer". Find a Grave. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ McCoy, Robert R. (2004). Chief Joseph, Yellow Wolf and the Creation of Nez Perce History in the Pacific Northwest. Indigenous Peoples and Politics. New York: Routledge. pp. 103–109. ISBN 0-415-94889-4.

- ^ "The Treaty Trail: U.S.-Indian Treaty Councils in the Northwest". Washington State Historical Society. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ Rigby, Barry (July 3, 1990). "Archie Phinney was a champion of Indian rights". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. p. 4-Centennial.

Further reading

- Beal, Merrill D. "I Will Fight No More Forever": Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1963.

- Bial, Raymond. The Nez Perce. New York: Benchmark Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7614-1210-7.

- Boas, Franz (1917). Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin tribes. Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection. Published for the American Folk-Lore Society by G.E. Stechert & Co. OCLC 2322072.

- Haines, Francis. The Nez Percés: Tribesmen of the Columbia Plateau. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955.

- Henry, Will. From Where the Sun Now Stands, New York: Bantam Books, 1976.

- Humphrey, Seth K. (1906). . The Indian Dispossessed (Revised ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 68571148 – via Wikisource.

- Josephy, Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Yale Western Americana series, 10. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1965.

- Judson, Katharine Berry (1912). Myths and legends of the Pacific Northwest, especially of Washington and Oregon. Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection (2nd ed.). Chicago: A.C. McClurg. OCLC 10363767. Oral traditions from the Chinook, Nez Perce, Klickitat and other tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

- Lavender, David Sievert. Let Me Be Free: The Nez Perce Tragedy. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 0-06-016707-6.

- Nerburn, Kent. Chief Joseph & the Flight of the Nez Perce: The Untold Story of an American Tragedy. New York: HarperOne, 2005. ISBN 0-06-051301-2.

- Pearson, Diane. The Nez Perces in the Indian Territory: Nimiipuu Survival. 2008.

- Stout, Mary. Nez Perce. Native American peoples. Milwaukee, WI: Gareth Stevens Pub, 2003. ISBN 0-8368-3666-9.

- Warren, Robert Penn. Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Who Called Themselves the Nimipu, "the Real People": A Poem. New York: Random House, 1983. ISBN 0-394-53019-5.

- Aoki, Haruo. 1989. Nez Perce Oral Narratives: Linguistics, Vol. 104. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Axtell, Horace and Margo Aragon. 1997. A Little Bit of Wisdom: Conversations with a Nez Perce Elder. Lewiston, Idaho: Confluence Press.

- Holt, Renée. 2012. "Decolonizing Indigenous Communities". in Unsettling America: Decolonization in Theory & Practice. April 18, 2012.

- Hunn, Eugene and James Selam. 2001. Nch’i-wána, 'the Big River': Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- James, Caroline. 1996. Nez Perce Women in Transition, 1877-1990. Moscow, Idaho: University of Idaho Press.

- Hormel, Leontina M. 2016. "Nez Perce Defending Treaty Lands in Northern Idaho". Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice, 28(1): 76-83.

- Josephy, Alvin. 2007. Nez Perce Country. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press.

- Josephy, Alvin. 1997. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- McCoy, Robert. 2004. Chief Joseph, Yellow Wolf, and the Creation of Nez Percé History in the Pacific Northwest. New York: Routledge.

- McWhorter, Lucullus Virgil. 1940. Yellow Wolf: His Own Story. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press.

- Phinney, Archie. 1969. Nez Percé Texts. New York: AMS Press.

- Slickpoo, Allen P. Sr. 1972. Nu moe poom tit wah tit (Nez Perce Legends). Lapwai, Idaho: Nez Perce Tribe.

- Tonkovich, Nicole. 2012. The Allotment Plot: Alice C. Fletcher, E. Jane Gay, and Nez Perce Survivance. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press.

- Trafzer, Clifford. 1987. Northwestern Tribes in Exile: Modoc, Nez Perce, and Palouse Removal to the Indian Territory. Sacramento: Sierra Oaks Publishing Co.

External links

- Official tribal site.

- Friends of the Bear Paw, Big Hole & Canyon Creek Battlefields.

- Nez Perce Horse Registry.

- Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission – member tribes include the Nez Perce.

- Nez Perce National Historic Park.

- Nez Perce National Historic Trail.

- The Nez Perce Essay by Deward E. Walker, Jr. and Peter N. Jones - University of Washington Digital Collection