Rachel's Tomb: Difference between revisions

revert to triple H: broseph, please, we both know what ownership means for a country |

Jiujitsuguy (talk | contribs) Undid revision 392543318 by Sol Goldstone (talk) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

|longitude = 35.202475 |

|longitude = 35.202475 |

||

|map_size = 220 |

|map_size = 220 |

||

|location = |

|||

|location = [[Bethlehem]], [[West Bank]]<ref name=bethlehem /> |

|||

|region = |

|region = |

||

|coordinates = |

|coordinates = |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

|archaeologists = |

|archaeologists = |

||

|condition = |

|condition = |

||

|ownership = |

|ownership = {{Flag icon|Israel}} Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs |

||

|public_access = |

|public_access = |

||

|website = |

|website = |

||

Revision as of 05:11, 24 October 2010

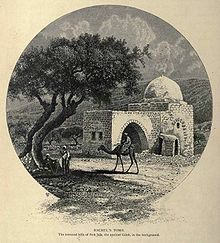

Illustration of the tomb, 1880 | |

| Type | tomb |

|---|---|

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | |

Rachel's Tomb (Hebrew: קבר רחל translit. Kever Rahel), is an ancient tomb believed to be the burial place of the biblical matriarch Rachel. The structure is located south of Jerusalem in Bethlehem.[1] Israel regards the tomb as being within the "Jerusalem envelope".[2] The tomb is venerated by the Abrahamic faiths and is considered the third holiest site in Judaism.[3] It is also viewed as the symbol of the return of the Jewish people to its ancient homeland.[4] Although doubts regarding Rachel's exact place of burial are raised in Talmudic literature, some Rabbinic material recognises the current location as authentic.[5] Others, relying on biblical texts, place her burial site northeast of Jerusalem in the vicinity of biblical Ramah, modern day ar-Ram.[6]

Historically, the site was known by the Arabs as the Dome of Rachel, (Arabic: translit. Qubbat Rakhil). Now it is also sometimes referred to as the Bilal ibn Rabah Mosque, and claimed by Muslims to have been built at the time of the Arab conquest.[7]

Biblical accounts and location

In the Hebrew Bible, Rachel and Jacob journey from Shechem to Hebron, a short distance from Ephrath, which is glossed as Bethlehem (35:16-21, 48:7). She dies on the way giving birth to Benjamin:

"And Rachel died, and was buried on the way to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem. And Jacob set a pillar upon her grave: that is the pillar of Rachel's grave unto this day." — Genesis 35:19-20

Today, along the ancient Bethlehem-Ephrath road, known as the "Route of the Patriarchs", on the right-hand side if traveling from Jerusalem, stands an ancient tomb traditionally believed to be that of Rachel. At the northern entrance to Bethlehem, this location has been recorded since 4th-century AD. Although it stands within the built-up area of Bethlehem, the tomb is now enclosed within the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier.

Others however suggest that the original location of Rachel's burial was in Benjaminite, not Judean, territory. Evidence for this is confirmed in the Book of Samuel where Saul would "encounter two men at Rachel's grave in the territory of Benjamin" (1 Sam 10:2). Furthermore, Jeremiah talks of the "sound of weeping emanating from Rachel's tomb that could be heard in Ramah" (Jer. 31:15). Ramah is identified with the Arab village north of Jerusalem, ar-Ram, which was also the departure for Saul's journey.[8] A possible location in the area could be the five stone monuments north of Hizma. Known as Qubur Beni Isra'in, the largest so-called tomb of the group, the function of which is obscure, has the name Qabr Umm beni Isra'in, that is, "tomb of the mother of the descendants of Israel".[6]

In the New Testament, a reference to Ramah and to the Jeremiah prophecy about Rachel weeping from her's tomb is found in the Gospel of Matthew (2:18), where this prophecy is considered to be fulfilled with the gruesome slaughter of boy children when the Herod was king:

- In Ramah was there a voice heard, lamentation, and weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children, and would not be comforted, because they are not.

Later traditions

The tomb of Rachel the Righteous is at a distance of 1½ miles from Jerusalem, in the middle of the field, not far from Bethlehem, as it says in the Torah. On Passover and Lag B’Omer many people – men and women, young and old – go out to Rachel's Tomb on foot and on horseback. And many pray there, make petitions and dance around the tomb and eat and drink. On the top of the tomb is a high dome, and on one side it is opened, and you enter a big courtyard surrounded by bricks.

Rabbi Moses Surait of Prague, 1650.[9]

Traditions regarding the site as the tomb at this location date back to the beginning of the 4th-century AD.[10] In the 7th century only a pyramid of stones marked the tomb.[11] In 1154 al-Idrisi writes "The tomb is covered by 12 stones and above is a dome vaulted over with stone." Benjamin of Tudela (1169–71) mentions a pillar made of 11 stones and a cupola resting on four columns "and all the Jews that pass by carve their names upon the stones of the pillar." Petachiah of Regensburg explains that the 11 stones represented the tribes of Israel, excluding Benjamin, since Rachel had died during his birth. All were marble, with that of Jacob on top."[10] In the 14-century, Antony of Cremona referred to the cenotaph as "the most wonderful tomb that I shall ever see. I do not think that with 20 pairs of oxen it would be possible to extract or move one of its stones." It was described by Franciscan pilgrim Nicolas of Poggibonsi (1346–50) as being 7 feet high and enclosed by a rounded tomb with three gates. By the 15th century, if not before, it had been appropriated by the Muslims and the Russian deacon Zozimos (1491-21) describes it as a mosque.[10] Felix Fabri, who visited about 1480–1483, reported that "this place is venerated alike by Muslims, Jews, and Christians".[12] In 1483 Bernhard von Breidenbach of Mainz described women praying at the tomb and collecting stones to take home, believing that they would ease their labour.[13][14]

Ottoman period

Non-Muslims were prohibited from visiting the tomb until 1615 when Muhammad, Pasha of Jerusalem, made repairs to the structure and gave the Jews exclusive use of the site.[15]

Ottoman firmans gave Jews in the Land of Israel the right of access to the site at the beginning of the nineteenth century.[7]

In 1788, walls were built to enclose the arches.[15] An 1824 report described "a stone building, evidently of Turkish construction, which terminates at the top in a dome. Within this edifice is the tomb. It is a pile of stones covered with white plaster, about 10 feet long and nearly as high. The inner wall of the building and the sides of the tomb are covered with Hebrew names, inscribed by Jews."[16]

Sir Moses Montefiore and Judith, Lady Montefiore visited the Land of Israel seven times. Lady Montefiore first saw Rachel's Tomb on their first visit, in 1828. The couple were childless, and Lady Montefiore was deeply moved by the tomb, which was in good condition at that time. Before the couple's next visit, in 1839, the Galilee earthquake of 1837 had heavily damaged the tomb.[17] In 1838 the tomb was described as "merely an ordinary Muslim Wely, or tomb of a holy person; a small square building of stone with a dome, and within it a tomb in the ordinary Muhammedan form; the whole plastered over with mortar. It is neglected and falling to decay; though pilgrimages are still made to it by the Jews. The naked walls are covered with names in several languages; many of them Hebrew."[11]

In 1841 Montefiore purchased the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. To conciliate Muslem susceptibility, he added a square vestibule with a mihrab to be used as a place of prayer for Muslims.[10][18] In 1845 he made further architectural improvements at the tomb.[9]

In the mid-1850s, the Arab e-Ta’amreh tribe were paid £30 annually by the Jews in an effort to prevent damage to the tomb.[19] In 1864, the Sefardi Jews of Bombay donated the necessary money to dig a well. Although Rachel's Tomb is only an hour and a half walk from the Old City of Jerusalem, many pilgrims found themselves very thirsty and unable to obtain fresh water.

During the late 19th century, land near the tomb was acquired by Nathan Strauss and Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. (During the first years of the Intifada, the Gush Etzion Regional Council managed to buy back ownership of about 10 dunams of Jewish-owned land near the tomb.)[20]

In 1912 the Ottoman Government permitted the Jews to repair the shrine itself, but not the antechamber.[21] In 1915 the structure had four walls, each about 7 m (23 ft.) long and 6 m (20 ft.) high. The dome, rising about 3 m (10 ft.), "is used by the Moslems for prayer; its holy character has hindered them from removing the Hebrew letters from its walls."[22]

British Mandate period

Three months after the British occupation of Palestine the whole place was cleaned and whitewashed by the Jews without protest from the Muslims. However, in 1921 when the Chief Rabbinate applied to the Municipality of Bethlehem for permission to perform repairs at the site, local Muslims objected.[21] In view of this, the High Commissioner ruled that, pending appointment of the Holy Places Commission provided for under the Mandate, all repairs should be undertaken by the Government. However, so much indignation was caused in Jewish circles by this decision that the matter was dropped, the repairs not being considered urgent.[21] In 1925 the Sephardic Jewish community requested permission to repair the tomb. The building was then made structurally sound and exterior repairs were effected by the Government, but permission was refused by the Jews (who had the keys) for the Government to repair the interior of the shrine. As the interior repairs were unimportant, the Government dropped the matter, in order to avoid controversy.[21]

During the riots of 1929, violence hampered regular visits by Jews to the tomb. In the same year, the Wakf demanded control of the site, claiming it was part of the neighboring Muslim cemetery. It also demanded to renew the old Muslim custom of purifying corpses in the tomb's antechamber.[23]

United Nations stance

Following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194 (December 11, 1948) which called for free access to all the holy places in Israel and the remainder of the territory of the former Palestine Mandate of Great Britain. In April 1949, the Jerusalem Committee prepared a document for the UN Secretariat in order to establish the status of the different holy places in the area of the former British Mandate for Palestine. It noted that ownership of Rachel's Tomb was claimed by both Jews and Muslims. The Jews claimed possession by virtue of a 1615 firman granted by the Pasha of Jerusalem which gave them exclusive use of the site and that the building, which had fallen into decay, was entirely restored by Moses Montefiore in 1845; the keys were obtained by the Jews from the last Muslim guardian at this time. The Muslims claimed the site was a place of Muslim prayer and an integral part of the Muslim cemetery within which it was situated. They stated that the Ottoman Government had recognised it as such and that it is included among the Tombs of the Prophets for which identity signboards were issued by the Ministry of Waqfs in 1898. They also asserted that the antechamber built by Montefiore was specially built as a place of prayer for Muslims. The UN ruled that the status quo, an arrangement approved by the Ottoman Decree of 1757 concerning rights, privileges and practices in certain Holy Places, apply to the site.[21]

Jordanian period

From 1948-67, the site was controlled by Jordan and protected by the Islamic wakf. In theory, free access was to be granted as stipulated in the 1949 Armistice Agreements, though Israelis, unable to enter Jordan, were prevented from visiting.[24] During this period the neighbouring Muslim cemetery was expanded, enveloping the immediate area surrounding the tomb.[15]

Israeli control

Following the Six Day War in 1967, Israel gained control of the West Bank, which included the tomb. Prime minister Levi Eshkol instructed that the tomb be included within the new expanded municipal borders of Jerusalem,[20] but citing security concerns, Moshe Dayan decided not to include it within the territory that was annexed to Jerusalem.[25]

Israeli enclave (1995-2002)

In accordance with guidelines set forth by the Oslo accords in 1995, the government of Israel was to determine the boundaries of areas which would be transferred to the Palestinian Authority. The tomb was situated 460 metres from the municipal border of Jerusalem, but the first draft placed Rachel's Tomb in Area A under PA jurisdiction. This aroused fierce right-wing opposition, with the Left viewing their protests as a convenient pretext to impede negotiations.[25] Menachem Porush, an aged ultra-Orthodox Knesset member, persuaded former prime minister Yitzhak Rabin that the tomb must remain under Israeli sovereignty.[26] Pressure from Jewish organisations and important figures made Rabin and foreign minister Shimon Peres reach a new agreement with Yasser Arafat that placed the tomb and the road leading to it in Area C under Israeli control. In addition, a yeshiva was established at the site to provide a constant Jewish presence. On December 1, 1995, Bethlehem, with the exception of the tomb enclave, passed under the full control of the Palestinian Authority. Jews could only reach it in bulletproof vehicles under military supervision.[7]

In early 1996 it was suspected that the Palestinians would carry out terrorist attacks at Rachel's Tomb. Fearing the tomb would be an easy target, Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a 13 foot high wall and adjacent military post.[27] In response, Palestinians claimed that "the Tomb of Rachel was on Islamic land" and that the structure was in fact a mosque built at the time of the Arab conquest in honour of Bilal ibn Rabah, an Ethiopian known in Islamic history as the first muezzin.[7]

At the end of September 1996, Arab riots broke out in Jerusalem over the opening of the Western Wall tunnel. After an attack on Joseph's Tomb and its subsequent takeover by Arabs, hundreds of residents of Bethlehem and the Aida refugee camp, led by the Palestinian Authority-appointed governor of Bethlehem, Muhammad Rashad al-Jabari, attacked Rachel's Tomb. They set the scaffolding which had been erected around it on fire and tried to break in. The IDF dispersed the mob with gunfire and stun grenades, and dozens were wounded.[7] In the following years, the Israeli-controlled site became a flashpoint between young Palestinian riotors who hurled stones, bottles and firebombs and IDF troops, who responded with tear gas and rubber bullets.[28]

A serious escalation occurred at the end of 2000 when the second intifada broke out. For forty-one days the tomb was attacked with gunfire. Fatah operatives and members of the Palestinian security services also attacked Rachel's Tomb. Palestinian daily Al-Hayat al-Jadida published an article describing the site as "one of the nails the Zionist movement hammered into many Palestinian cities....The tomb is false and was originally a Muslim mosque."[7] In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.[7]

Inclusion within West Bank barrier (2002-onwards)

The Israeli government decided in September 2002, that the tomb would be enclosed on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier. The short road to it was closed off inside concrete walls and firing positions. In 2003 the Rachel's Tomb Institute was founded. It provides a number of bullet-proof buses which travel each day to the tomb. The Israeli public-transportation system also runs a service to the area and approximately 4,000 people visit the tomb each month.[29]

In February 2005, the Israel Supreme Court rejected a Palestinian appeal to change the path of the security fence in the region of the tomb.[7]

The Palestinian ministry for endowments and religious affairs has defined Rachel's Tomb as a Muslim site.[7] In February 2010, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu announced that tomb, as well as the Cave of the Patriarchs, would become a part of the national Jewish heritage sites rehabilitation plan. The announcement sparked protests from the UN, Palestinian officials, Arab governments and the United States. A State Department spokesman criticized the move as provocative and unhelpful.[30][31] Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said the tomb was "not and never will be a Jewish site, but an Islamic site."[32]

Customs

Rachel is considered the "eternal mother", caring for her children when they are in distress especially for barren or pregnant woman. Jewish tradition teaches that Rachel weeps for her children and that when the Jews were taken into exile, she wept as they passed by her grave on the way to Babylonia. The Torah Ark Rachel's Tomb is covered with a curtain (Hebrew: parokhet) made from the wedding gown of Nava Applebaum, a young Israeli woman who was killed by Palestinian terrorists in a suicide bombing at Café Hillel in Jerusalem on the eve of her wedding.[33]

There is a tradition regarding the key that unlocked the door to the tomb. The key was about 15 centimetres (5.9 in) long and made of brass. The beadle kept it with him at all times, and it was not uncommon that someone would knock at his door in the middle of the night requesting it to ease the labor pains of an expectant mother. The key was placed under her pillow and almost immediately, the pains would subside and the delivery would take place peacefully.

Till this day there is an ancient tradition regarding a segulah or charm which is the most famous woman's ritual at the tomb.[34] A red string is tied around the tomb seven times then worn as a charm for fertility.[34] This use of the string is comparatively recent, though there is a report of its use to ward off diseases in the 1880s.[35]

Replicas

The tomb of Sir Moses Montefiore, adjacent to the Montefiore synagogue in Ramsgate, England, is a replica of Rachel's Tomb. During an 1841 visit to Palestine, Montifiore obtained permission from the Ottoman Turks to restore the tomb.[36]

References

- ^ Gilitz, David (2002). Davidson (ed.). Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 510. ISBN 9781576070048.

{{cite book}}:|author1-first=missing|author1-last=(help) - ^ Cheryl Rubenberg (2003). The Palestinians: in search of a just peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 424. ISBN 9781588262257. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Israel yearbook on human rights, Volume 36, Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University, 2006. pg. 324

- ^ Susan Sered, A Tale of Three Rachels: The Natural Herstory of a Cultural Symbol," in "Nashim: a journal of Jewish women's studies & gender issues, Issues 1-2", Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, 1998. "In the 1940s, by contrast, Rachel's Tomb became explicitly identified with the return to Zion, Jewish statehood and Allied victory."

- ^ Sharon, Moshe. Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Brill 2004, p. 190. ISBN 9004131973

- ^ a b Strickert, Frederick M. Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Liturgical Press, 2007. p. 69. ISBN 081465987X

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nadav Shragai (2 December 2007). "The Palestinian Authority and the Jewish Holy Sites in the West Bank: Rachel's Tomb as a Test Case". Jerusalem Viewpoints. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2007-11-25. [dead link]

- ^ Oded Lipschitz, Manfred Oeming. Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period, Eisenbrauns, 2006. p. 630-31. ISBN 157506104X

- ^ a b Susan Sereď, Our Mother Rachel, in Arvind Sharma, Katherine K. Young (eds.). The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4, SUNY Press, 1991, p. 21-24. ISBN 0791429679

- ^ a b c d Pringle, Denys. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pg. 176. ISBN 0521390370

- ^ a b Edward Robinson, Eli Smith. Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 & 1852, Volume 1, J. Murray, 1856. p. 218.

- ^ The book of Wanderings of Brother Felix Fabri. Vol. I, part II. Palestine Pilgrims Text Society. 1896. p. 547.[1]

- ^ Ruth Lamdan (2000). A separate people: Jewish women in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt in the sixteenth century. BRILL. p. 84. ISBN 9789004117471. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Reflections of God's Holy Land: A Personal Journey Through Israel, Thomas Nelson Inc, 2008. p. 57. ISBN 0849919568

- ^ a b c Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz. Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. ISBN 1576070042

- ^ The religious miscellany: Volume 3 Fleming and Geddes, 1824, p. 150

- ^ Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Frederick M. Strickert, Liturgical Press, 2007, pp. 112-3

- ^ Whittingham, George Napier. The home of fadeless splendour: or, Palestine of today, Dutton, 1921. pg. 314

- ^ Menashe Har-El (April 2004). Golden Jerusalem. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 9789652292544. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ a b Shragai, Nadav. The Palestinians who are shooting at the Rachel's Tomb compound have already singled it out as the next Jewish holy site which they want to 'liberate', Haaretz, (October 31, 2000)

- ^ a b c d e United Nations Conciliation Commission For Palestine: Committee on Jerusalem. (April 8, 1949)

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995 (reprint), [1915]. p. 32. ISBN 0802837840

- ^ Shragai, Nadav. The Palestinians Invent a Religious Claim: Rachel's Tomb termed "Bilal ibn", (December 2, 2007)

- ^ Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani. Israel and the Palestinian territories, Rough Guides, 1998. p. 395. ISBN 1858282489

- ^ a b Benveniśtî, Mêrôn. Son of the cypresses: memories, reflections, and regrets from a political life, University of California Press, 2007, P.44-45. ISBN 0520238257

- ^ Thousands at burial of Rabbi Menahem Porush, Jerusalem Post, (February 23, 2010)

- ^ Strickert, Frederick M. Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Liturgical Press, 2007. p. 135. ISBN 081465987X

- ^ Unrest during the late 1990's:

- Capital braces for violence, Jerusalem Post, (March 21, 1997).

- Israelis, Arabs clash in protest near Rachel's tomb, The Deseret News, (May 30, 1997).

- Palestinians stone soldiers by Rachel's Tomb, Jerusalem Post, (August 24, 1997).

- More West Bank Tension As Envoy Meets Arafat, New York Times, (September 13, 1998).

- ^ Mosdos Kever Rachel Imeinu: The Tomb

- ^ "Israel to include West Bank shrines in heritage plan". Reuters. 2010-02-22.

- ^ "US slams Israel over designating heritage sites". Washington Post. 2010-02-24. [dead link]

- ^ 'Rachel's Tomb was never Jewish', Jerusalem Post, March 7, 2010

- ^ ' Review of The Story of Rachel's Tomb, Joshua Schwartz,Jewish Quarterly Review 97.3 (2007) e100-e103 [2]

- ^ a b Susan Sered, Rachel's Tomb and the Milk Grotto of the Virgin Mary: Two Women's Shrines in Bethlehem, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, vol 2, 1986, pp7–22.

- ^ Susan Sered, Rachel's Tomb: The Development of a Cult, Jewish Studies Quarterly, vol 2, 1995, pp103–148.

- ^ Sharman Kadish, Jewish Heritage in England : An Architectural Guide, English Heritage, 2006, p. 62

Bibliography

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London, (Muhammad al-Idrisi: p.299)

- Sharon, Moshe (1999), Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Vol. II, B-C, BRILL, ISBN 9004110836 (p.177, ff)

External links

- Rachel's Tomb Website General Info., History, Pictures, Video, Visitor Info., Transportation

- A site dedicated to Rachel's Tomb