Shroud of Turin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

The Shroud of Turin (or Turin Shroud) is a linen cloth bearing the image of a man who appears to have been physically traumatized in a manner consistent with crucifixion. It is kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy.

The shroud is the subject of intense debate among some scientists, people of faith, historians, and writers regarding where, when, and how the shroud and its images were created. Some believe it is the cloth that covered Jesus of Nazareth when he was placed in his tomb and that his image was recorded on its fibers at or near the time of his proclaimed resurrection. Skeptics contend the shroud is a medieval hoax, forgery, or the result of natural processes that are not yet understood. Radiocarbon dating in 1988 by three independent teams of scientists yielded results indicating that the shroud was made during the Middle Ages, approximately 1300 years after Jesus lived. Follow-up analysis published in 2005, however, showed that the sample dated by the teams was taken from an area of the shroud that was not a part of the original cloth.[1] As of 2007, there is not a generally accepted carbon dating result for the shroud in the scientific literature.

Characteristics

The shroud is rectangular, measuring approximately 4.4 x 1.1 m (14.3 x 3.7 ft). The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill composed of flax fibrils. Its most distinctive characteristic is the faint, yellowish image of a front and back view of a naked man with his hands folded across his groin. The two views are aligned along the midplane of the body and pointing in opposite directions. The front and back views of the head nearly meet at the middle of the cloth. The views are consistent with an orthographic projection of a human body, but see Analysis of the image as the work of an artist.

The "Man of the Shroud" has a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length hair parted in the middle. He is muscular, and quite tall (1.75 m or roughly 5 ft 9 in) for a man of the first century (the time of Jesus' death) or for the Middle Ages (the time of the first uncontested report of the shroud's existence, and the proposed time of possible forgery). Reddish brown stains that have been confirmed to include whole blood are found on the cloth, showing various wounds that correlate with the yellowish image, the pathophysiology of crucifixion, and the Biblical description of the death of Jesus:[2]

- one wrist bears a large, round wound, apparently from piercing (the second wrist is hidden by the folding of the hands)

- upward gouge in the side penetrating into the thoracic cavity, a post-mortem event as indicated by separate components of red blood cells and serum draining from the lesion

- small punctures around the forehead and scalp

- scores of linear wounds on the torso and legs consistent with the Roman style of scourging (distinctive dumbbell wounds of a flagrum are present)

- swelling of the face from severe beatings

- streams of blood down both arms that include blood dripping from the main flow in response to gravity at an angle that would occur during crucifixion

- no evidence of either leg being fractured

- large puncture wounds in the feet as if pierced by a single spike

Other physical characteristics of the shroud include the presence of large water stains, and from a fire in 1532, burn holes and scorched areas down both sides of the linen due to contact with molten silver that burned through it in places while it was folded. Some small burn holes that apparently are not from the 1532 event are also present. In places, there are permanent creases due to repeated foldings, such as the line that is evident below the chin of the image.

On May 28, 1898, amateur Italian photographer Secondo Pia took the first photograph of the shroud and was startled by the negative in his darkroom.[citation needed] Negatives of the image give the appearance of a positive image, which implies that the shroud image is itself effectively a negative of some kind. Magician and paranormal skeptic Joe Nickell, however, notes that: "it's not a true photographic negative. The hair and beard are white in the positive image. Unless Jesus was an albino, there's a problem there."[3]

Image analysis by scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory found that rather than being like a photographic negative, the image unexpectedly has the property of decoding into a 3-D image of the man when the darker parts of the image are interpreted to be those features of the man that were closest to the shroud and the lighter areas of the image those features that were farthest. This is not a property that occurs in photography, and researchers could not replicate the effect when they attempted to transfer similar images using techniques of block print, engravings, a hot statue, and bas-relief.[2]

History

Possible history before the 14th century: The Image of Edessa

According to the Gospel of John (John 20:5–7), the Apostle Peter and the "beloved disciple" entered the sepulchre of Jesus, shortly after his resurrection — of which they were still unaware—and found the "linen clothes" that had wrapped his body and "the napkin, that was about his head."

There are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the fourteenth century.[4] However, none of these reports has been connected with certainty to the current cloth held in the Turin cathedral. Except for the Image of Edessa, none of the reports of these (up to 43) different "true shrouds" was known to mention an image of a body.

The Image of Edessa was reported to contain the image of the face of Christ (Jesus) and its existence is reported reliably since the sixth century. Some have suggested a connection between the Shroud of Turin and the Image of Edessa.[citation needed] No legend connected with that image suggests that it contained the image of a beaten and bloody Jesus. It was said to be an image transferred by Jesus to the cloth in life. This image is generally described as depicting only the face of Jesus, not the entire body. Proponents of the theory that the Edessa image was actually the shroud, led by Ian Wilson, theorize that it was always folded in such a way as to show only the face.

Three principal pieces of evidence are cited in favor of the identification with the shroud. John Damascene mentions the image in his anti-iconoclastic work On Holy Images [2], describing the Edessa image as being a "strip," or oblong cloth, rather than a square, as other accounts of the Edessa cloth hold. However, in his description, John still speaks of the image of Jesus' face when he was alive.

On the occasion of the transfer of the cloth to Constantinople in 944, Gregory Referendarius, archdeacon of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, preached a sermon about the artifact. This sermon had been lost, but was rediscovered in the Vatican Archives and translated by Mark Guscin Template:PDFlink in 2004. This sermon says that this Edessa cloth contained not only the face, but a full-length image, which was believed to be of Jesus. The sermon also mentions bloodstains from a wound in the side. Other documents have since been found in the Vatican library and the University of Leiden, Netherlands, confirming this impression. "Non tantum faciei figuram sed totius corporis figuram cernere poteris" (You can see not only the figure of a face, but [also] the figure of the whole body). (In Italian) (Cf. Codex Vossianus Latinus Q69 and Vatican Library Codex 5696, p. 35.)

In 1203, a Crusader knight named Robert de Clari claims to have seen the cloth in Constantinople: "Where there was the Shroud in which our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself upright so one could see the figure of our Lord on it." After the Fourth Crusade, in 1205, the following letter was sent by Theodore Angelos, a nephew of one of three Byzantine Emperors who were deposed during the Fourth Crusade, to Pope Innocent III protesting the attack on the capital. From the document, dated 1 August 1205: "The Venetians partitioned the treasures of gold, silver, and ivory while the French did the same with the relics of the saints and the most sacred of all, the linen in which our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after his death and before the resurrection. We know that the sacred objects are preserved by their predators in Venice, in France, and in other places, the sacred linen in Athens." (Codex Chartularium Culisanense, fol. CXXVI (copia), National Library Palermo)[5]

Unless it is the Shroud of Turin, then the location of the Image of Edessa since the 13th century is unknown.

Some historians suggest that the shroud was captured by the knight Otto de la Roche[6] who became Duke of Athens, but that he soon relinquished it to the Knights Templar. It was subsequently taken to France, where the first known keeper of the Turin Shroud had links both to the Templars as well the descendants of Otto. Some speculate that the shroud could have been a major part of the famed 'Templar treasure' that treasure hunters still seek today.

14th century

The known provenance of the cloth now stored in Turin dates to 1357, when the widow of the French knight Geoffroi de Charny, a - it is said - descendant of Templar Geoffroy de Charney who burned at the stake with Jacques de Molay, had it displayed in a church at Lirey, France (diocese of Troyes). In the Museum Cluny in Paris, the coats of arms of this knight and his widow can be seen on a pilgrim medallion, which also shows an image of the Shroud of Turin.

During the fourteenth century, the shroud was often publicly exposed, though not continuously, because the bishop of Troyes, Henri de Poitiers, had prohibited veneration of the image. Thirty-two years after this pronouncement, the image was displayed again, and King Charles VI of France ordered its removal to Troyes, citing the impropriety of the image. The sheriffs were unable to carry out the order.

In 1389, the image was denounced as a fraud by Bishop Pierre D'Arcis in a letter to the Avignon Antipope Clement VII, mentioning that the image had previously been denounced by his predecessor Henri de Poitiers, who had been concerned that no such image was mentioned in scripture. Bishop D'Arcis continued, "Eventually, after diligent inquiry and examination, he discovered how the said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, to wit, that it was a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed." (In German: [3].) The artist is not named in the letter.

The letter of Bishop D'Arcis also mentions Bishop Henri's attempt to suppress veneration, but notes that the cloth was quickly hidden "for 35 years or so," thus agreeing with the historical details already established above. The letter provides an accurate description of the cloth: "upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man, that is to say, the back and the front, he falsely declaring and pretending that this was the actual shroud in which our Saviour Jesus Christ was enfolded in the tomb, and upon which the whole likeness of the Saviour had remained thus impressed together with the wounds which He bore."

Despite the pronouncement of Bishop D'Arcis, Antipope Clement VII (first antipope of the Western Schism) prescribed indulgences for pilgrimages to the shroud, so that veneration continued, though the shroud was not permitted to be styled the "True Shroud." [4]

Alternate 14th century origins

The Second Messiah by Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas argues that the Shroud's image is that of the final Knights Templar leader, Jacques de Molay.

On Friday, 13 October 1307, the Templars were arrested by Philip the Fair under the authority of Pope Clement V. De Molay was nailed to a door and tortured but not killed, and his almost comatose body was wrapped in a cloth and left for 30 hours to recover. According to the hypothesis of Dr. Alan A. Mills in his article "Image formation on the Shroud of Turin," in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 1995, vol. 20 No. 4, pp 319–326, convection currents from the lactic acid in de Molay's perspiration created the image. The image corresponds to what would have been produced by a volatile chemical if the intensity of the color change were inversely proportional to the distance of the cloth from the body, and the slightly bent position accounts for the extension of the hands onto the thighs, something not possible if the body had been laid flat.

Further, according to Knight and Lomas, de Molay, and co-accused Geoffroy de Charney, were then cared for by brother Jean de Charney, whose family retained the shroud after de Molay's execution on 19 March 1314.

Apart from Knight and Lomas' scenario, there is a reliable connection between Shroud of Turin and the Templars: Geoffroi de Charny's widow Jeanne de Vergy is the first reliably recorded owner of the Turin shroud; his uncle, Geoffrey de Charney, was Preceptor of Normandy for the Knights Templar. This uncle is the same Geoffrey de Charney who was initially sentenced to lifetime imprisonment with de Molay, and was burned with de Molay in 1314 after both proclaimed their innocence, recanting torture-induced confessions.

15th century

In 1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs, moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, Doubs, to provide protection against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter Margaret. It was later moved to Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs. After Humbert's death, canons of Lirey fought through the courts to force the widow to return the cloth, but the parliament of Dole and the Court of Besançon left it to the widow, who traveled with the shroud to various expositions, notably in Liège and Geneva.

The widow sold the shroud in exchange for a castle in Varambon, France in 1453. Louis of Savoy, the new owner, stored it in his capital at Chambery in the newly built Saint-Chapelle, which Pope Paul II shortly thereafter raised to the dignity of a collegiate church. In 1464, the duke agreed to pay an annual fee to the Lirey canons in exchange for their dropping claims of ownership of the cloth. Beginning in 1471, the shroud was moved between many cities of Europe, being housed briefly in Vercelli, Turin, Ivrea, Susa, Chambery, Avigliana, Rivoli, and Pinerolo. A description of the cloth by two sacristans of the Sainte-Chapelle from around this time noted that it was stored in a reliquary: "enveloped in a red silk drape, and kept in a case covered with crimson velours, decorated with silver-gilt nails, and locked with a golden key."

16th century to present

In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. Some have suggested that there was also water damage from the extinguishing of the fire. However, there is some evidence that the watermarks were made by condensation in the bottom of a burial jar in which the folded shroud may have been kept at some point. In 1578, the shroud arrived again at its current location in Turin. It was the property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to the Holy See.

In 1988, the Holy See agreed to a radiocarbon dating of the relic, for which a small piece from a corner of the shroud was removed, divided, and sent to laboratories. (More on the testing is seen below.) Another fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud on 11 April 1997, but fireman Mario Trematore was able to remove it from its heavily protected display case and prevent further damage. In 2002, the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing and thirty patches were removed. This made it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from view. Using sophisticated mathematical and optical techniques, a ghostly part-image of the body was found on the back of the shroud in 2004. Italian scientists had exposed the faint imprint of the face and hands of the figure. The most recent public exhibition of the Shroud was in 2000 for the Great Jubilee. The next scheduled exhibition is in 2025.

The controversy

The origin of the relic is hotly disputed. Researchers have coined the term sindonology to describe its general study (from Greek σινδων—sindon, the word used in the Gospel of Mark to describe the type of cloth that Joseph of Arimathea bought to use as Jesus' burial cloth).

Theories of image formation

The image on the cloth has many peculiar and closely studied Template:PDFlink, for example, it is entirely superficial, not penetrating into the cloth fibers under the surface, so that the flax and cotton fibers are not colored; the image yarn is composed of discolored fibers placed side by side with non-discolored fibers so many striations appear. Thus the cloth is not simply dyed, though many other explanations, natural and otherwise, have been suggested for the image formation. Alone among published researchers, McCrone believed the entire image to be composed of pigment. Other results have shown the image to be a discoloration, not a "coloration."

Miraculous formation

Many believers have hypothesized that the image on the shroud was produced by a side effect of the Resurrection of Jesus, purposely left intact as a rare physical aid to understanding and believing in Jesus' dual nature as man and God.[citation needed] Some have asserted that the shroud collapsed through the glorified body of Jesus, pointing to certain X-ray-like impressions of the teeth and the finger bones. Others assert that radiation streaming from every point of the revivifying body struck and discolored every opposite point of the cloth, forming the complete image through a kind of supernatural pointillism using inverted shades of blue-gray rather than primary colors. Because these specific explanations, and dozens of others like them, posit the intervention or influence of a being or beings outside the observable constraints of nature, there is no limit to their imagination and construction.

Carbohydrate layer

A scientific theory involves known effects upon a dead body, and materials in contact with it, by the early phases of decomposition. The cellulose fibers making up the shroud's substance are coated with a thin carbohydrate layer of starch fractions, various sugars, and other impurities. This layer is very thin (180–600 nm) and was discovered by applying phase-contrast microscopy. It is thinnest where the image is and appears to carry the color, while the underlying cloth is uncolored. This carbohydrate layer would itself be essentially colorless, but in some places has undergone a chemical change producing a straw, yellow color. The reaction involved is similar to that which takes place when sugar is heated to produce caramel.

In a paper entitled "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction may explain the image formation,"[7] R.N. Rogers and A. Arnoldi propose that amines from a recently deceased human body will have Maillard reactions with the shroud's carbohydrate layer within a reasonable time, before liquid decomposition products stain or damage the cloth. The gases produced by a dead body are extremely reactive chemically and within a few hours, in an environment such as a tomb, a body starts to produce heavier amines in its tissues such as putrescine and cadaverine. These will produce the color seen in the carbohydrate layer. This raises questions, however, as to why the images (both ventral and dorsal views) are so photorealistic, and why they were not destroyed by later decomposition products (a question obviated if the Resurrection occurred, or if a body was removed from the cloth within the required time frame).

Auto-oxidation

Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas (1997) claim that the image on the shroud is that of Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Order of the Knights Templar, arrested for heresy at the Paris Temple by Philip IV of France on 13 October 1307. De Molay suffered torture under the auspices of the Chief Inquisitor of France, William Imbert. His arms and legs were nailed, possibly to a large wooden door. According to Knight and Lomas, after the torture De Molay was laid on a piece of cloth on a soft bed; the excess section of the cloth was lifted over his head to cover his front and he was left, perhaps in a coma, for perhaps 30 hours. They claim that the use of a shroud is explained by the Paris Temple keeping shrouds for ceremonial purposes.

De Molay survived the torture but was burned at the stake on 19 March 1314 together with Geoffroy de Charney, Templar preceptor of Normandy. De Charney's grandson was Jean de Charney who died at the battle of Poitiers. After his death, his widow, Jeanne de Vergy, purportedly found the shroud in his possession and had it displayed at a church in Lirey.

Knight and Lomas base their argument partly on the 1988 radiocarbon dating and Mills' 1995 research about a chemical reaction called auto-oxidation and they claim that their theory accords with the factors known about the creation of the shroud and the carbon dating results. The counter argument is that the Templars acquired the shroud upon one of the crusades[citation needed] and brought it to France where it remained a secret until Jean de Charney died.

Photographic image production

Skeptics have proposed many means for producing the image in the Middle Ages. Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince (1994) proposed that the shroud is perhaps the first ever example of photography, showing the portrait of its purported maker, Leonardo da Vinci. According to this theory, the image was made with the aid of a "magic lantern," a simple projecting device, or by means of a camera obscura and light-sensitive silver compounds applied to the cloth.

Although Leonardo was born a century after the first documented appearance of the cloth, supporters of this theory propose that the original cloth was an inferior fake, which was replaced with a superior hoax created by Leonardo. However, no contemporaneous reports indicate a sudden change in the quality of the image. The Turin Library holds a drawing of an old man that is widely but not universally accepted as a self-portrait by Leonardo. As the image depicts a man with a prominent brow and cheekbones and a beard, some consider that it resembles the image on the Shroud and have suggested that as part of a complex hoax, Leonardo may have placed his own portrait on the Shroud as the face of Christ. There is also conjecture that he was commissioned by the royal family of Turin, with whom he was friends, to create a work which could return to Turin that which had been lost for so many years.

However, such theories are not taken seriously by most academic scholars.

The photography theory also needs to account for lighting directionality, which produces shadowing in photographs, and is absent from the Turin Shroud. Analysis including side-by-side photos of Shroud and self-photo by Prof. Nicholas Allen using means available to da Vinci, was written in 2000 by STURP photographer Barrie Schwortz. Template:PDFlink

Painting

In 1977, a team of scientists selected by the Holy Shroud Guild developed a program of tests to conduct on the Shroud, designated the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP). Anastasio Cardinal Ballestrero, the archbishop of Turin, granted permission, despite disagreement within the Church. The STURP scientists conducted their testing over five days in 1978. Walter McCrone, a member of the team, upon analyzing the samples he had, concluded in 1979 that the image is actually made up of billions of submicron pigment particles.[citation needed] The only fibrils that had been made available for testing of the stains were those that remained affixed to custom-designed adhesive tape applied to thirty-two different sections of the image. (This was done in order to avoid damaging the cloth.) According to McCrone, the pigments used were a combination of red ochre and vermillion tempera paint. The Electron Optics Group of McCrone Associates published the results of these studies in five articles in peer-reviewed journals: Microscope 1980, 28, 105, 115; 1981, 29, 19; Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 1987/1988, 4/5, 50 and Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 77–83. STURP, upon learning of his findings, confiscated McCrone's samples, and brought in other scientists to replace him. In McCrone's words, he was "drummed out" of STURP and continued to defend the analysis he had performed, becoming a prominent proponent of the position that the Shroud is a forgery. As of 2004, no other scientists have been able to confirm or refute McCrone's results with independent experiments, simply because the Vatican refuses to cooperate.

Other microscopic analysis of the fibers seems to indicate that the image is strictly limited to the carbohydrate layer, with no additional layer of pigment visible. Proponents of the position that the Shroud is authentic say that no known technique for hand application of paint could apply a pigment with the necessary degree of control on such a nano-scale fibrillar surface plane.

In the television program "Decoding The Past: The Shroud of Turin," The History Channel reported the official finding of STURP that no pigments were found in the shroud image and multiple scientists asserted this conclusion on camera. No hint of controversy over this claim was suggested. The program stated that a NASA scientist organized STURP in 1976 (after being surprised to find depth-dimensional information encoded within the shroud image); no mention of the Holy Shroud Guild was made.

Solar masking, or "shadow theory"

In March 2005, N.D. Wilson, an instructor at New Saint Andrews College and amateur sindonologist, announced in an informal article in Books and Culture magazine that he had made a near duplicate of the shroud image by exposing dark linen to the sun for ten days under a sheet of glass on which a positive mask had been painted. His method, though admittedly crude and preliminary, has nonetheless attracted the attention of several sindonologists, notably the late Raymond Rogers[citation needed] of the original STURP team, and Antonio Lombatti[citation needed], founder of the skeptical shroud journal Approfondimento Sindone. Wilson's method is notable because it does not require any conjectures about unknown medieval technologies and is compatible with claims that there is no pigment on the cloth. However, the experiment has not been repeated and the images have yet to face microscopic and chemical analysis. In addition, concerns have been raised about the availability or affordability of medieval glass large enough to produce the image and the method's compatibility with Fanti's claim that the original image is doubly superficial.

Using a bas-relief

Another theory suggests that the Shroud may have been formed using a bas-relief sculpture. Researcher Jacques di Costanzo, noting that the Shroud image seems to have a three-dimensional quality, suggested that perhaps the image was formed using an actual three-dimensional object, like a sculpture. While wrapping a cloth around a life-sized statue would result in a distorted image, placing a cloth over a bas-relief would result in an image like the one seen on the shroud. To demonstrate the plausibility of his theory, Costanzo constructed a bas-relief of a Jesus-like face and draped wet linen over the bas-relief. After the linen dried, he dabbed it with ferric oxide and gelatin mixture. The result was an image similar to that of the Shroud. Similar results have been obtained by author Joe Nickell. Instead of painting, the bas-relief could also be heated and used to burn an image into the cloth.

Second Image on back of cloth

During restoration in 2002, the back of the cloth was photographed and scanned for the first time. The journal of the Institute of Physics in London published a peer-reviewed Template:PDFlink on this subject on April 14, 2004. Giulio Fanti and Roberto Maggiolo of the University of Padua - Italy, are the authors. They describe an image on the reverse side, much fainter than that on the front, consisting primarily of the face and perhaps hands. Like the front image, it is entirely superficial, with coloration limited to the carbohydrate layer. The images correspond to, and are in registration with, those on the other side of the cloth. No image is detectable in the dorsal view of the shroud.

Supporters of the Maillard reaction theory point out that the gases would have been less likely to penetrate the entire cloth on the dorsal side, since the body would have been laid on a stone shelf. At the same time, the second image makes the electrostatic hypothesis probable because a double superficiality is typical of coronal discharge and the photographic hypothesis is somewhat less probable.

Analysis of the Shroud

Radiocarbon dating

In 1988, the Holy See agreed to permit six centers to independently perform radiocarbon dating on portions of a swatch taken from a corner of the shroud, but at the last minute they changed their minds and permitted only three research centers to independently perform radiocarbon dating. All three, Oxford University, the University of Arizona, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, agreed with a dating in the 13th to 14th centuries (1260–1390).[8] The scientific community had asked the Holy See to authorize more samples, including from the image-bearing part of the shroud, but this request was refused. One possible account for the reluctance is that if the image is genuine, the destruction of parts of it for purposes of dating could be considered sacrilege.

Radiocarbon dating under typical conditions is a highly accurate science and, for materials up to 2000 years old, can often produce dating to within one year of the correct age.[citation needed] Nonetheless, there are many possibilities for error as well. It was developed primarily for use on objects recently unearthed or otherwise shielded from human contact until shortly before the test is conducted, unlike the shroud. Dr. Willi Wolfli, director of the Swiss laboratory that tested the shroud, stated, "The C-14 method is not immune to grossly inaccurate dating when non-apparent problems exist in samples from the field. The existence of significant indeterminate errors occurs frequently."

Chemical properties of the sample site

Another argument against the results of the radiocarbon tests was made in a study by Anna Arnoldi of the University of Milan and Raymond Rogers, retired Fellow of the University of California Los Alamos National Laboratory. By ultraviolet photography and spectral analysis they determined that the area of the shroud chosen for the test samples differs chemically from the rest of the cloth. They cite the presence of Madder-root dye and aluminum-oxide mordant (a dye-fixing agent) specifically in that corner of the shroud and conclude that this part of the cloth was mended at some point in its history. Plainly, repairs would have utilized materials produced at or slightly before the time of repair, carrying a higher concentration of carbon than the original artifact.

A 2000 study by Joseph Marino and Sue Benford, based on x-ray analysis of the sample sites, shows a probable seam from a repair attempt running diagonally through the area from which the sample was taken. These researchers conclude that the samples tested by the three labs were more or less contaminated by this repair attempt. They further note that the results of the three labs show an angular skewing corresponding to the diagonal seam: the first sample in Arizona dated to 1238, the second to 1430, with the Oxford and Swiss results falling in between. They add that the variance of the C-14 results of the three labs falls outside the bounds of the Pearson's chi-square test, so that some additional explanation should be sought for the discrepancy.

Microchemical tests also find traces of vanillin in the same area, unlike the rest of the cloth. Vanillin is produced by the thermal decomposition of lignin, a complex polymer and constituent of flax. This chemical is routinely found in medieval materials but not in older cloths, as it diminishes with time. The wrappings of the Dead Sea scrolls, for instance, do not test positive for vanillin.

These conclusions suggest that other samples, from a part of the shroud not mended or tampered with, would need to be tested in order to ascertain an accurate date for the shroud. Since the Vatican has refused to allow such testing, the age of the shroud remains uncertain. The Vatican has physical possession and therefore legal control of the shroud, but it cannot claim to be a disinterested or objective arbiter. [citation needed]

Raymond Rogers' 20 January, 2005 paper[1] in the scientific journal Thermochimica Acta argues that the sample cut from the shroud in 1988 was not valid. Rogers concludes, based upon the vanillin loss, that the shroud is between 1,300 and 3,000 years old.

Skeptics contend that the carbon dating was accurate and that Rogers's study was flawed. One skeptic argues, "In his paper, Ray Rogers relies on papers that were neither peer-reviewed nor published in legitimate scientific journals for his belief that the radiocarbon date was taken from a patch ingeniously rewoven into the Shroud linen so that its presence could not be detected."[9]

Bacterial residue

A team led by Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, MD, adjunct professor of microbiology, and Stephen J. Mattingly, PhD, professor of microbiology at the University of Texas at San Antonio have expounded an argument involving bacterial residue on the shroud[10]. There are examples of ancient textiles that have been grossly misdated, especially in the earliest days of radiocarbon testing. Most notable of these is mummy 1770 of the British Museum, whose bones were dated some 800 to 1000 years earlier than its cloth wrappings. The skewed results were thought to be caused by organic contaminants on the wrappings similar to those proposed for the shroud. Pictorial evidence dating from c. 1690 and 1842[11] indicates that the corner used for the dating and several similar evenly-spaced areas along one edge of the cloth were handled each time the cloth was displayed, the traditional method being for it to be held suspended by a row of five bishops. Wilson and others contend that repeated handling of this kind greatly increased the likelihood of contamination by bacteria and bacterial residue compared to the newly discovered archaeological specimens for which carbon-14 dating was developed. Bacteria and associated residue (bacteria by-products and dead bacteria) carry additional carbon and would skew the radiocarbon date toward the present.

Harry E. Gove of the University of Rochester, the nuclear physicist who designed the particular radiocarbon tests used on the shroud in 1988, stated, "There is a bioplastic coating on some threads, maybe most." If this coating is thick enough, according to Gove, it "would make the fabric sample seem younger than it should be." Skeptics, including Rodger Sparks, a radiocarbon expert from New Zealand, have countered that an error of thirteen centuries stemming from bacterial contamination in the Middle Ages would have required a layer approximately doubling the sample weight.[12] Because such material could be easily detected, fibers from the shroud were examined at the National Science Foundation Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence at the University of Nebraska. Pyrolysis-mass-spectrometry examination failed to detect any form of bioplastic polymer on fibers from either non-image or image areas of the shroud. Additionally, laser-microprobe Raman analysis at Instruments SA, Inc. in Metuchen, NJ, also failed to detect any bioplastic polymer on shroud fibers.

Detailed discussion of the carbon-dating

There are two books with detailed treatment of the Shroud's carbon dating, including not only the scientific issues but also the events, personalities and struggles leading up to the sample taking. The books offer opposite views on how the dating should have been conducted, and both are critical of the methodology finally employed. These books have been reviewed on amazon.com

In Relic, Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud (1996; ISBN 0750303980), Harry Gove provides an account with large doses of light humor and heavy vitriol. Particular scorn is poured on STURP (the US scientific team studying the Shroud) and Luigi Gonella, then scientific adviser to the Archbishop of Turin, Cardinal Ballestrero. Gove describes in great detail the mammoth struggle between Prof Carlos Chagas, chairman of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and Cardinal Ballestrero, with Gove and Gonella as the main combatants from each side. He provides a detailed record of meetings, telephone conversations, faxes, letters and maneuvers. Gove initially accepted the dating as accurate, but in the epilogue notes that the bioplastic contamination theory seemed to have some evidence to support it.

The Rape of the Turin Shroud by William Meacham (2005; ISBN 1411657691) devotes 100 pages to the carbon dating. Meacham is also highly critical of STURP and Gonella, and also of Gove. He describes the planning process from a very different perspective (both he and Gove were invited along with 20 other scholars to a conference in Turin in 1986 to plan the C-14 protocol) and focuses on what he claims was the major flaw in the dating: taking only one sample from the corner of the cloth. Meacham reviews the main scenarios that have been proposed for a possibly incorrect dating, and claims that the result is a "rogue date" because of the sample location and anomalies. He points out that this situation could easily be resolved if the Church authorities would simply allow another sample to be dated, with appropriate laboratory testing for possible embedded contaminants.

Material historical analysis

Much recent research has centered on the burn holes and water marks. The largest burns certainly date from the 1532 fire (another series of small, round burns in an "L" shape seems to date from an undetermined earlier time), and it was assumed that the water marks were also from this event. However, in 2002, Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito presented a paper Template:PDFlink at the IV Symposium Scientifique International in Paris stating that many of these marks stem from a much earlier time because the symmetries correspond more to the folding that would have been necessary to store the cloth in a clay jar (like cloth samples at Qumran) than to that necessary to store it in the reliquary that housed it in 1532.

According to master textile restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg of Hamburg, a seam in the cloth corresponds to a fabric found only at the fortress of Masada near the Dead Sea, which dated to the first century. The weaving pattern, 3:1 twill, is consistent with first-century Syrian design, according to the appraisal of Gilbert Raes of the Ghent Institute of Textile Technology in Belgium. Flury-Lemberg stated, "The linen cloth of the Shroud of Turin does not display any weaving or sewing techniques which would speak against its origin as a high-quality product of the textile workers of the first century." However, Joe Nickell notes that no examples of herringbone weave are known from the time of Jesus. The few samples of burial cloths that are known from the era are made using plain weave.[13]

Biological and medical forensics

Details of crucifixion technique

The piercing of the wrists rather than the palms goes against traditional Christian iconography, especially that of the Middle Ages. Many modern scholars suggest that crucifixion victims were generally nailed through the wrists. A skeleton discovered recently in Israel shows that at least some were nailed between the radius and ulna. This was not common knowledge in the Middle Ages. Proponents of the shroud's authenticity contend that a medieval forger would have been unlikely to know this operational detail of an execution method almost completely discontinued centuries earlier.

Blood stains

There are several reddish stains on the shroud suggesting blood. McCrone (see above) identified these as containing iron oxide, theorizing that its presence was likely due to simple pigment materials used in medieval times. Other researchers, including Alan Adler, a chemist specializing in analysis of porphyrins, identified the reddish stains as type AB blood and interpreted the iron oxide as a natural residue of that element always found in mammalian red blood cells.

Drs. Heller and Adler further studied the dark red stains. Applying pleochroism, birefringence, and chemical analysis, they determined that, unlike the medieval artist’s pigment which contains iron oxide contaminated with manganese, nickel, and cobalt, the iron oxide on the shroud was relatively pure but later proven to be iron oxide resulting from blood stains (Heller, J.H., Adler, A.D. 1980). Dr. Adler then applied microspectrophotometric analysis of a "blood particle" from one of the fibrils of the shroud and identified hemoglobin (in the acid methemoglobin, which formed due to great age and denaturation). Further tests by Heller and Adler established, within claimed scientific certainty, the presence of porphyrin, bilirubin, albumin, and protein. Interestingly, when proteases (enzymes which break up protein within cells) were applied to the fibril containing the "blood," the blood dissolved from the fibril leaving an imageless fibril (Heller, J.H., and Adler, A.D. 1981). Template:PDFlink. It is uncertain whether the blood stains were produced at the same time as the image, which Adler and Heller attributed to premature aging of the linen.[14] Working independently with a larger sample of blood-containing fibrils, pathologist Pier Baima Bollone, using immunochemistry, confirms Heller and Adler’s findings and identifies the blood as being from the AB blood group (Baima Bollone, P., La Sindone-Scienza e Fide 1981).

The particular shade of red of the supposed blood stains are problematic, according to skeptics of the shroud's authenticity. Normally, whole blood stains discolor relatively rapidly, turning to a black-brown shade, while these stains range from a red to a brown color. Skeptics claim that: " Blood has not been identified on the shroud directly, but it has been identified on sticky tape that was used to lift fibrils from the shroud. Dried, aged blood is black. The stains on the shroud are red. Forensic tests on the red stuff have identified it as red ocher and vermilion tempera paint." and that if there is blood: "it could be the blood of some 14th century person. It could be the blood of someone wrapped in the shroud, or the blood of the creator of the shroud, or of anyone who has ever handled the shroud, or of anyone who handled the sticky tape. But even if there were blood on the shroud, that would have no bearing on the age of the shroud or on its authenticity."[15]

In addition, skeptics have claimed that the so called blood flows on th shroud are unrealistically neat. Leading forensic pathologist Michael Baden notes that real blood never oozes in nice neat rivulets, it gets clotted in the hair. He concludes that: "Human beings don't produce this kind of pattern."[16]

Pollen grains

Researchers of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem reported the presence of pollen grains in the cloth samples, showing species appropriate to the spring in Israel. However, these researchers, Avinoam Danin and Uri Baruch, were working with samples provided by Max Frei, a Swiss police criminologist who had previously been censured for faking evidence. Independent review of the strands showed that one strand out of the 26 provided contained significantly more pollen than the others, perhaps pointing to deliberate contamination.[17]

Another item of note is that the olive trees surrounding Jerusalem would have been in full bloom at the time, meaning that there should have been a significant amount of olive tree pollen on the Shroud. However, there does not seem to be any at all.

The Israeli researchers also detected the outlines of various flowering plants on the cloth, which they say would point to March or April and the environs of Jerusalem, based on the species identified. In the forehead area, corresponding to the crown of thorns if the image is genuine, they found traces of Gundelia tournefortii, which is limited to this period of the year in the Jerusalem area. This analysis depends on interpretation of various patterns on the shroud as representing particular plants. Skeptics point out that the available images cannot be seen as unequivocal support for any particular plant species due to the generally indistinct "blobiness," even under powerful microscopes, of these tiny, spotty impressions.

Again, these pollen grains could have been lost when the Shroud was 'restored' in June/July 2002, following an exhibition in 2000.

Another problem is that the Catholic veneration of the Shroud by the faithful probably involved touching it. Public display of the Shroud in the past may have contributed to its contamination not only by bacteria, as described above, but also by pollen and other air-borne plant material

Sudarium of Oviedo

In the northern Spanish city of Oviedo, there is a small bloodstained piece of linen that is also revered as one of the burial cloths of Jesus mentioned in John 20:7 as being found in the 'empty' tomb. John refers to a "Sudarium" (σουδαριον) that covered the head and the "linen cloth" or "bandages" (οθονιον — othonion) that covered the body. The Sudarium of Oviedo is traditionally held to be this cloth that covered the head of Jesus.

The Sudarium's existence and presence in Oviedo is well attested to since the eighth century and in Spain since the seventh century. Before these dates the location of the Sudarium is less certain, but some scholars trace it to Jerusalem in the first century.

Forensic analysis of the bloodstains on the shroud and the Sudarium suggest that both cloths could have covered the same head at nearly the same time. Based on the bloodstain patterns, the Sudarium would have been placed on the man's head while he was in a vertical position, presumably while still hanging on the cross. This cloth was then presumably removed before the shroud was applied.

A 1999 study [5] by Mark Guscin, a member of the multidisciplinary investigation team of the Spanish Center for Sindonology, investigated the relationship between the two cloths. Based on history, forensic pathology, blood chemistry (the Sudarium also is reported to have type AB blood stains), and stain patterns, he concluded that the two cloths covered the same head at two distinct, but close moments of time. Avinoam Danin (see above) concurred with this analysis, adding that the pollen grains in the Sudarium match those of the shroud.

Pollen from Jerusalem could have followed any number of paths to find its way to the Sudarium and only indicates location, not the dating of the cloth. [6]

Digital image processing

Using techniques of digital image processing, several additional details have been reported by scholars.

NASA researchers Jackson, Jumper, and Stephenson report detecting the impressions of coins placed on both eyes after a digital study in 1978. The coin on the right eye was claimed to correspond to a Roman copper coin produced in AD 29 and 30 in Jerusalem, while that on the left was claimed to resemble a lituus coin from the reign of Tiberius.[18]

Greek and Latin letters were discovered written near the face (Piero Ugolotti, 1979). These were further studied by André Marion, professor at the École supérieure d'optique and his student Anne Laure Courage, graduate engineer of the École supérieure d'optique, in the Institut d'optique théorique et appliquée in Orsay (1997). On the right side they cite the letters ΨΣ ΚΙΑ. They interpret this as ΟΨ — ops "face" + ΣΚΙΑ — skia "shadow," though the initial letter is missing. This interpretation has the problem that it is grammatically incorrect in Greek, because "face" would have to appear in the genitive case. On the left side they report the Latin letters IN NECE, which they suggest is the beginning of IN NECEM IBIS, "you will go to death," and ΝΝΑΖΑΡΕΝΝΟΣ — NNAZARENNOS (a grossly misspelled "the Nazarene" in Greek). Several other "inscriptions" were detected by the scientists, but Mark Guscin Template:PDFlink (himself a shroud proponent) reports that only one is at all probable in Greek or Latin: ΗΣΟΥ. This is the genitive of "Jesus," but missing the first letter.

These claims are rejected by skeptics, because there is no recorded Jewish tradition of placing coins over the eyes of the dead and because of the spelling errors in the reported text. (Cf. Antonio Lombatti [7]) Guscin concurs with the skeptics who hold that these details are based on highly subjective impressions, much like the results of a Rorschach test.

Textual criticism

The Gospel of John is sometimes cited as evidence that the shroud is a hoax because English translations typically use the plural word "cloths" or "clothes" for the covering of the body: "Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and seeth the linen clothes [othonia] lie, and the napkin [Sudarium], that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself" (John 20:6–7, KJV). Shroud proponents hold that "linen clothes" refers to the Shroud of Turin, while the "napkin" refers to the Sudarium of Oviedo.

The Gospel of John also states, "Nicodemus . . . brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about an hundred pound weight. They took the body of Jesus, and wound it in linen clothes with the spices, as the manner of the Jews is to bury" (John 19:39–40, KJV). No traces of spices have been found on the cloth. Frederick Zugibe, a medical examiner, reports [8] that the body of the man wrapped in the shroud appears to have been washed before wrapping. It would be odd for this to occur after the anointing, so some proponents have suggested that the shroud was a preliminary cloth that was then replaced before the anointing, because there was not enough time for the anointing due to the Sabbath. However, there is no empirical evidence to support these theories. Some supporters suggest that the plant bloom images detected by Danin may be from herbs that were simply strewn over the body due to the lack of preparation time mentioned in the New Testament, with the visit of the women on Sunday thus presumed to be for the purpose of completing the anointing of the body.

Joe Nickell notes that the Shroud cloth is incompatible with New Testament accounts of Jesus' burial. He claims that: "John's gospel (19:38-42, 20:5-7) specifically states that the body was 'wound' with 'linen clothes' and a large quantity of burial spices (myrrh and aloes). Still another cloth (called 'the napkin') covered his face and head. In contrast, the Shroud of Turin represents a single, draped cloth (laid under and then over the 'body') without any trace of the burial spices."[19]

Analysis of the image as the work of an artist

Painters of the 14th century

This article possibly contains original research. (September 2007) |

One of the striking features of the image on the Shroud of Turin is its accuracy as a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional human form. It is the accuracy of the three-dimensional information present in the image that has suggested to experts that it has been created as a photographic projection, either deliberately or as part of a natural process.

In light of Dr. Walter McCrone's conclusions that the image had been painted with "thin watercolor paint," the possible author of such a painting has been sought. If the whereabouts of the Shroud of Turin are considered as known from the mid-14th century, is there a known painter who could have created it?

In Christian art, the depiction of the naked male figure, in the form of either the crucified Christ or the body of Christ being prepared for burial, is a common subject of both painting and sculpture. This was the case in the Medieval and early Renaissance periods. In early Medieval art, the naked figure was often highly stylized. In the 13th century, this became less the case and by 1300 there was sometimes a great impression of realism in the depiction of the naked male figure in sculpture.

By 1300, several painters who were firmly Medieval in most ways strove to depict in two-dimensions the suffering crucified Christ with realism and solidity of form. Foremost among these traditional painters was Duccio of Siena, whose small crucifixion scene, which forms one of the back panels of the Maesta, shows three convincingly realistic, though anatomically imprecise, male figures. Giotto, of the next generation of painters, was born about 1267. He is regarded as the artist most able in his day to capture an appearance of solidity and three-dimensionality in his painting. His fame was extensive. He had several commissions, including the Arena Chapel in Padua that was the equal of Michelangelo's commission to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel two hundred years later. But Giotto did not have the skill required to paint a face as three-dimensional or a body as anatomically accurate as that of the Shroud of Turin. The leading painters in Italy whose lives span the period of 1350, are Altichiero and Giusto de Menabuoi, who like Giotto, were active in Padua, in Northern Italy. Giusto's faces are flat and simplified compared with those of Giotto. Likewise, the best faces painted by Altichiero do not stand up to close examination of their three-dimensional qualities. Neither does his demonstrated understanding of anatomy. Throughout the rest of Europe, painted depictions of the crucifixion were stylized, with exaggerated anatomical features. This did not change until the effect of the Italian Renaissance upon Northern painters in the mid-15th century.

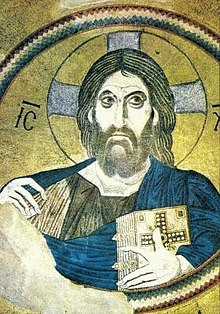

Correspondence with Christian iconography

As a depiction of Jesus, the image on the shroud corresponds to that found throughout the history of Christian iconography. For instance, the Pantocrator mosaic at Daphne in Athens is strikingly similar. Skeptics attribute this to the icons being made while the Image of Edessa was available, with this appearance of Jesus being copied in later artwork, and in particular, on the Shroud. In opposition to this viewpoint, the locations of the piercing wounds in the wrists on the Shroud do not correspond to artistic representations of the crucifixion before close to the present time. In fact, the Shroud was widely dismissed as a forgery in the 14th century for the very reason that the Latin Vulgate Bible stated that the nails had been driven into Jesus' hands and Medieval art invariably depicts the wounds in Jesus' hands. Modern biblical translations recognize this as an error in translating the Greek text of the Gospels and the lack of a clear word, as in English, which defines the wrist as a separate anatomical entity from the hand which it supports. Additionally, modern medical science reveals that the metacarpal bones are incapable of supporting a crucified body, and that, contrary to the almost universally held belief in the 14th century, the nails had to have been driven through the victim's wrists, as depicted in the Shroud.

Analysis of proportion

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The man on the image is taller than the average first-century Palestinian and the right hand has longer fingers than the left, along with a significant increase of length in the right forearm compared to the left.[20]

Analysis of optical perspective

One further objection to the Shroud turns on what might be called the "Mercator projection" argument. The shroud in two dimensions presents a three-dimensional image projected onto a planar (two-dimensional) surface, just as in a photograph or painting. A true burial shroud, however, would have rested nearly cylindrically across the three-dimensional facial surface, if not more irregularly. The result would be an unnatural lateral distortion, a strong widening to the sides, in contrast to the kind of normal photographic image a beholder would expect, let alone the strongly vertically elongated image on the Shroud fabric.

But this argument is disputed by the paper presented at Template:PDFlink. Essentially, distortions can be small if the Shroud was not lying tight against the body.

Variegated Images

Banding on the Shroud is background noise, which causes us to see the gaunt face, long nose, deep eyes, and straight hair. These features are caused by dark vertical and horizontal bands that go across the eyes. Using enhancement software (Fourier transform filters), the effect of these filters can be minimized. The result is a more detailed version of the face.

The Shroud in the Catholic Church

The Shroud was given to the Pope by the House of Savoy in 1983. As with all relics of this kind, the Roman Catholic Church has made no pronouncements claiming it is Christ's burial shroud, or that it is a forgery. The matter has been left to the personal decision of the faithful. In the Church's view, whether the cloth is authentic or not has no bearing whatsoever on the validity of what Christ taught.

The late Pope John Paul II stated in 1998, "Since we're not dealing with a matter of faith, the church can't pronounce itself on such questions. It entrusts to scientists the tasks of continuing to investigate, to reach adequate answers to the questions connected to this shroud." He showed himself to be deeply moved by the image of the shroud and arranged for public showings in 1998 and 2000.

Because the image itself is a focus of meditation for many believers, even a definitive proof that the image does not date from the first century would likely not stop devotion to the object, which would then become something of an icon of the crucifixion. In any case, Catholics meditate on the events of the Passion, not on the object itself, " . . . in immediate forgetfulness of the object," as St. John of the Cross put it. And in that sense, any image of Christ's shroud has a universal meaning. Pope John Paul II called the Shroud of Turin " . . . the icon of the suffering of the innocent of all times."

Some have suggested that if the identity of the Shroud with the Image of Edessa were to be definitively proven, the Church would have no moral right to retain it and would then be compelled to return it to the Ecumenical Patriarch or some other Eastern Orthodox body, because if this was the case, it would have been stolen from the Orthodox Church at some time during the Crusades. Some Russian Orthodox consider that with the fall of Constantinople, the title of "emperor" passed on to Russia, so they would have preeminent rights to the Shroud over all the other Orthodox. Yet many other Orthodox Christians feel this desire of some Russian Orthodox is just an expression of nationalism.

In any case, the removal from Edessa of the Image of Edessa by the conquest of Byzantine Emperor Romanus I in 944, arguably marks the first break in the legitimate chain of title.

Because of the continuing dispute about its authenticity, some Catholic theologians have called the Shroud of Turin a sign of contradiction.

The 'restoration' of 2002

In the summer of 2002, the Shroud was subjected to an aggressive restoration which shocked the worldwide community of Shroud researchers and was condemned by most. Authorized by the Archbishop of Turin as a beneficial conservation measure, this operation was based on the claim that the charred material around the burn holes was causing continuing oxidation which would eventually threaten the image. It has been labeled unnecessary surgery that destroyed scientific data, removed the repairs done in 1534 that were part of the Shroud's heritage, and squandered opportunities for sophisticated research.

Detailed comments on this operation were published by various Shroud researchers.[21] In 2003, the principal restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, a textile expert from Switzerland, published a book with the title Sindone 2002: L'intervento conservativo — Preservation — Konservierung (ISBN 88-88441-08-5). She describes the operation and the reasons it was believed necessary. In 2005, William Meacham, an archaeologist who has studied the Shroud since 1981, published the book The Rape of the Turin Shroud (ISBN 1-4116-5769-1) which is fiercely critical of the operation. He rejects the reasons provided by Flury-Lemberg and describes in detail what he calls "a disaster for the scientific study" of the relic.

References

This article has an unclear citation style. |

- ^ a b Rogers, Raymond N.: "Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin." Thermochimica Acta, Volume 425, Issue 1–2 (January 20 2005), pages 189–194

- ^ a b Heller, John H. Report on the Shroud of Turin. Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0395339677

- ^ The Joe Nickell Files: The Shroud of Turin

- ^ Humber, Thomas: The Sacred Shroud. New York: Pocket Books, 1980. ISBN 0-671-41889-0

- ^ "The letter was rediscovered in the archive of the Abbey of St. Caterina a Formiello, Naples; it is folio CXXVI of the Chartularium Culisanense, originating in 1290, a copy of which came to the Naples as a result of close political ties with the imperial Angelus-Comnenus family from 1481 on. The Greek original had been lost." in: [1]; see also: a photo of the document

- ^ Eyewitnesses reports by Geoffroy de Villehardouin and Robert de Clari, accounts of the Fourth Crusade

- ^ Rogers, R.N. and Arnoldi, A.: "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction (Maillard reaction) may explain the image formation." In Ames, J.M. (Ed.): Melanoidins in Food and Health, Volume 4, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2003, pp. 106–113. ISBN 92-894-5724-4

- ^ Damon, P. E. (1989-02). "Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Nature. 337 (6208): 611–615. doi:10.1038/337611a0. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.skeptic.ws/shroud/ see: A Skeptical Response to Ray Rogers' Thermochimica Acta paper on the Shroud of Turin by Steven Schafersman

- ^ Microbiology meets archaeology in a renewed quest for answers

- ^ Ian Wilson, The Blood and the Shroud. New York: Free Press, 1998. ISBN 0684853590

- ^ Debate of Roger Sparks and William Meacham on alt.turin-shroud

- ^ Nickell, Joe: Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: Latest Scientific Findings. Prometheus Books, 1998. ISBN 1-57392-272-2

- ^ Heller, J.H. and Adler, A.D.: "Blood on the Shroud of Turin." Applied Optics 19:2742–4 (1980)

- ^ http://www.skepdic.com/shroud.html

- ^ Baden, Michael. 1980. Quoted in Reginald W. Rhein, Jr., The Shroud of Turin: Medical examiners disagree. Medical World News, Dec. 22, p. 50.

- ^ Nickell, Joe: "Pollens on the 'shroud': A study in deception". Sceptical Inquirer, Summer 1994., pp 379–385

- ^ Jean-Philippe Fontanille The coins of Pontius Pilate

- ^ Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud'

- ^ Angier, Natalie. 1982. Unraveling the Shroud of Turin. Discover Magazine, October, pp. 54-60.

- ^ shroud.com

Further reading

- Baima Bollone, P., La Sindone-Scienza e Fide 1981, 169–179.

- Baime Bollone, P., Jorio, M., Massaro, A.L., Sindon 23, 5, 1981.

- Baima Bollone, Jorio, M., Massaro, A.L., Sindon 24, 31, 1982, pp 5–9.

- Baima Bollone, P., Gaglio, A. Sindon 26, 33, 1984, pp 9–13.

- Baima Bollone, P., Massaro, A.L. Shroud Spectrum 6, 1983, pp 3–6.

- Damascene, John: On Holy Images [9].

- Guscin, Mark: "The 'Inscriptions' on the Shroud." British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, November 1999.

- Kersten, H., Gruber, E.R., 1992. The Jesus Conspiracy: Turin Shroud and the Truth about the Resurrection (Paperback) ISBN 1852306661.

- Lombatti, Antonio: "Doubts Concerning the Coins over the Eyes." British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, Issue 45, 1997.

- Marino, Joseph G. and Benford, M. Sue. Evidence for the Skewing of the C-14 Dating of the Shroud of Turin due to Repairs. Sindone 2000 Conference, Orvieto, Italy. Template:PDFlink

- Mills, A.A.: "Image formation on the Shroud of Turin" Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 20, 1995.

- McCrone, W.C., The Microscope, 29, 1981, p. 19–38.

- McCrone, W.C., Skirius, C., The Microscope, 28, 1980, pp 1–13.

- Nickell, Joe: "Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud'." Skeptical Inquirer, Sept. 2001. [10]

- Picknett, Lynn and Prince, Clive: The Turin Shroud: In Whose Image?, Harper-Collins, 1994 ISBN 0-552-14782-6.

- Zugibe, Frederick: "The Man of the Shroud was Washed." Sindon N.S. Quad. 1, June 1989.

- Decoding the Past: The Shroud of Turin, 2005 History Channel video documentary, produced by John Joseph, written by Julia Silverton.

External links

- Official site of the custodians of the Shroud in Turin

- Discovery of image on reverse side of shroud (The Guardian)

- Discovery News article on Wilson's method

- Jesus' Shroud? Recent Findings Renew Authenticity Debate by National Geographic Society

- Photo in the News: Shroud of Turin by National Geographic Society

Pro-authenticity sites

- Speech by Pope John Paul about the shroud

- "Shroud of Christ?" (A "Secrets of the Dead" episode on PBS)

- "Forensic Medicine and the Shroud of Turin"

- Shroud of Turin Story - Guide to the Facts

Skeptical sites

- Shroud of Turin, sacred relic or religious hoax?

- 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia

- McCrone Research Institute presentation of its findings Assertion that the shroud is a painting.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA