Shroud of Turin

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth bearing the image of a man who appears to have been physically traumatized in a manner consistent with crucifixion. It is presently kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. Some believe it is the cloth that covered Jesus when he was placed in his tomb and that his image was somehow recorded on its fibers. Skeptics contend it is a medieval hoax or forgery. It is the subject of intense debate among some scientists, believers, historians and writers regarding where, when and how the shroud and its image were created.

General observations

The shroud is rectangular, measuring approximately 4.4 x 1.1 m. The cloth is woven in a herringbone twill and is composed of flax fibrils entwined with cotton fibrils. It bears the image of a front and dorsal view of a naked man with his hands folded across his groin. The two views are aligned along the midplane of the body and pointing in opposite directions. The front and back views of the head nearly meet at the middle of the cloth. The views are consistent with an orthographic projection of a human body.

The "Man of the Shroud" has a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length hair parted in the middle. He is well proportioned and muscular, and quite tall (1.75 m) for a man of the first century (the time of Jesus' death) or for the Middle Ages (the time of the first uncontested report of the shroud's existence, and the proposed time of possible forgery). Dark red stains, either blood or a substance meant to be perceived as blood, are found on the cloth, showing various wounds:

- at least one wrist bears a large round wound, apparently from piercing (The second wrist is hidden by the folding of the hands.)

- in the side, again apparently from piercing

- small wounds around the forehead

- scores of linear wounds on the torso and legs, apparently from scourging

On May 28, 1898 an amateur Italian photographer, Secondo Pia, took the first photograph of the shroud and was startled by the resulting undeveloped negative. The negative seemed to give the appearance of a positive image, which implies that the shroud image (which is primarily brownish-yellow on off-white) is itself effectively a negative of some kind. Observers often feel that the detail and heft of the man on the shroud is greatly enhanced in the photographic negative, producing an unexpected effect. Pia's negative intensified interest in the shroud and sparked renewed efforts to determine its origin.

History

Possible history before the 14th century: The Image of Edessa

There are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the fourteenth century. (See Humbert, 1978.) However, none of these reports have been connected with certainty to the current cloth held in the Turin cathedral. Except for the Image of Edessa, none of the reports of these (up to 43) different "true shrouds" were known to mention an image of a body.

Some have suggested a connection between the Shroud of Turin and the Image of Edessa. That image was reported reliably since the middle of the sixth century. No legend connected with that image suggests that it contained the image of a beaten and bloody Jesus, but rather it was said to be an image transferred by Jesus to the cloth in life. This image is generally described as depicting only the face of Jesus, not the entire body. Proponents of the theory that the Edessa image was actually the shroud, led by Ian Wilson, theorize that it was always folded in such a way as to show only the face.

John Damascene mentions the image in his anti-iconoclastic work On Holy Images [1], describing the Edessa image as being a "strip", or oblong cloth, rather than a square, as other accounts of the Edessa cloth hold.

On August 15, 944, the cloth of Edessa was forcibly removed from Edessa to Constantinople. On the occasion of the transfer of the cloth, Gregory Referendarius, archdeacon of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople held a sermon about the artefact. This sermon had been lost, but was rediscovered in the Vatican Archives and translated by Mark Guscin [2] in 2004. This sermon says that this Edessa Cloth contained not only the face, but a full-length image, which was believed to be of Jesus. The sermon also mentions bloodstains from a wound in the side. Other documents have since been found in the Vatican library and the University of Leiden, Netherlands, confirming this impression. "[Non tantum] faciei figuram sed totius corporis figuram cernere poteris" (You can see [not only] the figure of a face, but [also] the figure of the whole body). (In Italian: [3].) (Cf. Codex Vossianus Latinus Q69 and Vatican Library Codex 5696, p. 35.)

In 1203, a Crusader Knight named Robert de Clari claims to have seen the cloth in Constantinople: "Where there was the Shroud in which our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself upright so one could see the figure of our Lord on it." After the Fourth Crusade, in 1205, the following letter was sent by Theodore Angelos, a nephew of one of three Byzantine Emperors who were deposed during the Fourth Crusade, to Pope Innocent III protesting the attack on the capital. From the document, dated 1 August 1205: "The Venetians partitioned the treasures of gold, silver, and ivory while the French did the same with the relics of the saints and the most sacred of all, the linen in which our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after his death and before the resurrection. We know that the sacred objects are preserved by their predators in Venice, in France, and in other places, the sacred linen in Athens." (Codex Chartularium Culisanense, fol. CXXVI (copia), National Library Palermo)

Unless it is the Shroud of Turin, then the location of the Image of Edessa since the 13th century is unknown.

14th century

The known provenance of the cloth now stored in Turin dates to 1357, when the widow of the French knight Geoffroy de Charny had it displayed in a church at Lirey, France (diocese of Troyes). In the Museum Cluny in Paris, the coats of arms of this knight and his widow can be seen on a pilgrim medallion, which also shows an image of the Shroud of Turin.

During the fourteenth century, the shroud was often publicly exposed, though not continuously, since the bishop of Troyes, Henri de Poitiers, had prohibited veneration of the image. Thirty-two years after this pronouncement, the image was displayed again, and King Charles VI of France ordered its removal to Troyes, citing the impropriety of the image. The sheriffs were unable to carry out the order.

In 1389 the image was denounced as a fraud by Bishop Pierre D'Arcis in a letter to the Avignon pope, mentioning that the image had previously been denounced by his predecessor Henri de Poitiers, who had been concerned that no such image was mentioned in scripture. Bishop D'Arcis continued, "Eventually, after diligent inquiry and examination, he discovered how the said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, to wit, that it was a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed." (In German: [4].) The artist is not named in the letter.

The letter of Bishop D'Arcis also mentions Bishop Henri's attempt to suppress veneration, but notes that the cloth was quickly hidden "for 35 years or so", thus agreeing with the historical details already established above. The letter provides an accurate description of the cloth: "upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man, that is to say, the back and the front, he falsely declaring and pretending that this was the actual shroud in which our Savior Jesus Christ was enfolded in the tomb, and upon which the whole likeness of the Savior had remained thus impressed together with the wounds which He bore."

If the claims of this testimony are correct, it would be consistent with the radiocarbon dating of the shroud (see below). From the point of view of many skeptics, it is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that the shroud is a forgery.

Despite the pronouncement of Bishop D'Arcis, Antipope Clement VII (first antipope of the Western Schism) prescribed indulgences for pilgrimages to the shroud, so that veneration continued, though the shroud was not permitted to be styled the "True Shroud". [5]

15th century

In 1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs, moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, France to provide protection against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter. It was later moved to Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs. After Humbert's death, canons of Lirey fought through the courts to force the widow to return the cloth, but the parliament of Dole and the Court of Besançon left it to the widow, who travelled with the shroud to various expositions, notably in Liege and Geneva.

The widow sold the image in exchange for a castle in Varambon, France in 1453. Louis of Savoy, the new owner, stored it in his capital at Chambery in the newly-built Saint-Chapelle, which Pope Paul II shortly thereafter raised to the diginity of a collegiate church. In 1464, the duke agreed to pay an annual fee to the Lirey canons in exchange for their dropping claims of ownership of the cloth. Beginning in 1471, the shroud was moved between many cities of Europe, being housed briefly in Vercelli, Turin, Ivrea, Susa, Chambery, Avigliano, Rivoli and Pinerolo. A description of the cloth by two sacristans of the Sainte-Chapelle from around this time noted that it was stored in a reliquary: "enveloped in a red silk drape, and kept in a case covered with crimson velours, decorated with silver-gilt nails, and locked with a golden key".

16th century to present

In 1532 the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically-placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. Some have suggested that there was also water damage from the extinguishing of the fire. In 1578 the shroud arrived again at its current location in Turin. It was the property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to the Holy See.

In 1988 the Holy See agreed to a Carbon 14 dating of the relic, for which a small piece from a corner of the shroud was removed, divided, and sent to laboratories. (More on the testing is seen below.) Another fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud in 1997, but a fireman was able to remove it from its display case and prevent further damage. In 2002 the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing and thirty patches were removed. This made it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from view.

The most recent public exhibition of the Shroud was in 2000 for the Great Jubilee. The next scheduled exhibition is in 2025.

The controversy

The origin of the relic is hotly disputed. Those who believe it to have been used in Christ's burial have coined the term sindonology to describe its study (from Greek σινδων—sindon, the word used in the Gospel of Mark to describe the cloth that Joseph of Arimathea bought to use as Jesus' burial cloth). The term is generally not used by skeptics of the mystical origins of the relic.

It may be impossible to ever fully resolve the controversy over the cloth because believers are willing to accept supernatural explanations for the creation of the image, which cannot be definitively disproven, while most skeptics do not consider any supernatural explanations to be acceptable. Three independent radiocarbon datings of the shroud date it to 13th to 14th centuries.

Theories of image formation

The image on the cloth is entirely superficial, not penetrating into the cloth fibers under the surface, so that the flax and cotton fibers are not colored. Thus the cloth is not simply dyed, though many other explanations, natural and otherwise, have been suggested for the image formation.

Miraculous formation

Many believers consider the image to be a side effect of the Resurrection of Jesus, sometimes proposing semi-natural effects that might have been part of the process. Naturally, none of these theories is verifiable, and skeptics reject them out of hand. Some have suggested that the shroud collapsed through the glorified body of Jesus. Supporters of this theory point to certain x-ray-like impressions of the teeth and the finger bones. Others suggest that radiation caused by the miraculous event may have burned the image into the cloth.

Carbohydrate layer

A scientific theory that does not rule out the association of the shroud with Christ involves the gases that escape from a decomposing body in the early phases of decomposition. The cellulose fibers making up the shroud's cloths are coated with a thin carbohydrate layer of starch fractions, various sugars and other impurities. This layer is very thin (180 - 600 nm) and was discovered by applying phase contrast microscopy. The layer is thinnest where the image is. It appears that the carbohydrate layer carries the color, while the underlying cloth is uncolored. Naturally, such a layer would be essentially colorless, but in some places it has undergone a chemical change, producing a straw yellow color. The reaction involved is similar to that which takes place when sugar is heated to produce caramel.

In a paper entitled "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction (Maillard reaction) may explain the image formation," (see References) R. N. Rogers and A. Arnoldi suggest a natural explanation (which does not rule out a supernatural invocation of a natural process). Maillard reactions of amines from a human body with the carbohydrate layer will occur within a reasonable time, before liquid decomposition products stain or damage the cloth. The gases produced by a dead body are extremely reactive chemically. Within a few hours, in an environment such as a tomb, a body starts to produce heavier amines in its tissues such as putrescine and cadaverine. This will produce the color seen in the carbohydrate layer. But it raises questions about why the image (both ventral and dorsal views) is so photorealistic and why the images were not destroyed by later decomposition products (a question obviated if the Resurrection occurred, or if a body was removed from the cloth within the required timeframe).

Photographic image production

Skeptics have proposed many means for producing the image in the Middle Ages. Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince (1994) proposed that the shroud is perhaps the first ever example of photography, showing the portrait of its maker, Leonardo da Vinci. According to this theory, the image was made with the aid of a Laterna Magica, a simple projecting device, and light-sensitive silver compounds applied to the cloth. However, Leonardo was born a century after the first documented appearence of the cloth. Supporters of this theory thus propose that the original cloth was a poor fake, for which Leonardo's superior hoax was substituted, though no contemporaneous reports indicate a sudden change in the quality of the image.

Painting

In 1977, a team of scientists selected by the Holy Shroud Guild developed a program of tests to conduct on the Shroud, designated the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP). Cardinal Ballestrero, the archbishop of Turin, granted permission, despite disagreement within the church. The STURP scientists conducted their testing over five days in 1978. Walter McCrone, a member of the team, upon analyzing the samples he had, concluded in 1979 that the image is actually made up of billions of submicron pigment particles. The only fibrils that had been made available for testing of the stains were those that remained affixed to adhesive-backed tape applied to thirty-two different sections of the image. (This was done in order to avoid damaging the cloth.) According to McCrone, the pigments used were a combination of red ochre and vermilion tempera paint. The Electron Optics Group of McCrone Associates published the results of these studies in five articles in peer-reviewed journals: Microscope 1980, 28, 105, 115; 1981, 29, 19; Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 1987/1988, 4/5, 50 and Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 77-83. STURP, upon learning of his findings, confiscated McCrone's samples and brought in other scientists to replace him. In McCrone's words, he was "drummed out" of STURP, and continued to defend the analysis he had performed, becoming a prominent proponent of the position that the Shroud is a forgery. As of 2004, no other scientists have confirmed McCrone's results with independent experiments.

Other microscopic analysis of the fibers seems to indicate that the image is strictly limited to the carbohydrate layer, with no additional layer of pigment visible. Proponents of the position that the Shroud is authentic say that no known technique for hand-application of paint could apply a pigment with the necessary degree of control on such a nano-scale fibrillar surface plane.

Second Image on back of cloth

As mentioned above, during restoration in 2002, the back side of the cloth was photographed and scanned for the first time. The journal of the Institute of Physics in London published a peer-reviewed article on this subject on April 14, 2004. Giulio Fanti and Roberto Maggiolo of the University of Padua, Italy are the authors. They describe an image on the reverse side, much fainter than that on the other side, consisting primarily of the face and hands. Like the front image, it is entirely superficial, with coloration limited to the carbohydrate layer. The images correspond to, and are in registration with, those on the other side of the cloth. No image is detectable in the dorsal view section of the shroud.

Supporters of the Maillard reaction theory point out that the gases would have been less likely to penetrate the entire cloth on the dorsal side, since the body would have been laid on a stone shelf.

At the same time, the second image makes the photographic theory somewhat less probable.

Analysis of the Shroud

Radiocarbon dating

In 1988, the Holy See permitted three research centers to independently perform radiocarbon dating on portions of a swatch taken from the corner of the shroud. All three, Oxford University, the University of Arizona, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology agreed, with a dating in the 13th to 14th centuries (1260-1390). The scientific community had asked the Holy See to authorize more samples, including from the image-bearing part of the shroud, but this request was refused. If the image is genuine, the destruction of parts of it for purposes of dating could be considered sacrilege. This is one possible account for the reluctance to release more samples, both in 1988 and when more samples have subsequently been requested. Another possible explanation is a reluctance to have the shroud definitively dated.

Radiocarbon dating is a highly accurate science, and for materials up to 2000 years old can produce dating to within one year of the correct age. Nonetheless, there are many possibilities for error as well. Dr. Willi Wolfli, director of the Swiss laboratory that tested the shroud, stated, "The C14 method is not immune to grossly inaccurate dating when non-apparent problems exist in samples from the field. The existence of significant indeterminant errors occurs frequently."

Bacterial residue

Several phenomena have been cited that might account for an erroneous dating. Those supporting image formation by miraculous means point out that a singular Resurrection event could have skewed the proportion of Carbon 14 in the cloth in singular ways. Naturalistic explanations for the discrepancy include smoke particles from the fire of 1532 and bacterial residue that would not have been removed by the testing teams' methods.

The argument involving bacterial residue is perhaps the strongest, since there are many examples of ancient textiles that were gravely misdated, especially in the earliest days of radiocarbon testing. Most notable of these is mummy 1770 of the British Museum, whose bones were dated some 800–1000 years earlier than its cloth wrappings. Proponents also point out that the corner used for the dating would have been handled more often than other parts of the shroud, increasing the likelihood of contamination by bacteria and bacterial residue. Bacteria and associated residue (bacteria by-products and dead bacteria) carry additional carbon and would skew the radiocarbon date toward the present.

The nuclear physicist Harry E. Gove of the University of Rochester, who designed the particular radiocarbon test used, stated, "There is a bioplastic coating on some threads, maybe most." According to Gove, if this coating is thick enough, it "would make the fabric sample seem younger than it should be." Skeptics, including Rodger Sparks, a radiocarbon expert from New Zealand, have countered that an error of thirteen centuries stemming from bacterial contamination in the Middle Ages would have required a layer approximately doubling the sample weight.

Chemical properties of the sample site

Another argument against the results of the radiocarbon tests was made in a study by Anna Arnoldi of the University of Milan and Raymond Rogers, retired Fellow of the University of California Los Alamos National Laboratory. By ultraviolet photography and spectral analysis, they deterimined that the site chosen for the test samples of the cloth is chemically different from the rest of the cloth. They cite the presence of Madder root dye and aluminum oxide mordent (a dye-fixing agent) specifically in that corner of the shroud and conclude that that part of the cloth was mended at some point in its history.

Microchemical tests also find traces of vanillin in the same area, unlike the rest of the cloth. Vanillin is produced by the thermal decomposition of lignin, a complex polymer and constituent of flax. This chemical is routinely found in medieval materials, but not in older cloths, as it diminishes with time. The wrappings of the Dead Sea scrolls, for instance, do not test positive for vanillin.

This aspect of the controversy can likely only be settled by more radiocarbon tests, which as noted, the Holy See does not presently allow, citing fear of damage to the cloth.

Medieval repairs to the cloth

A final possible source of error in the dating of the cloth would be if fibers from medieval repairs were mixed into the sample areas. A 2000 study by Joseph Marino and Sue Benford suggests, based on x-ray analysis of the sample sites shows a probable seam from an apparent repair attempt. These researchers conclude that the samples tested by the three labs were more or less contaminated by this repair attempt. They further note that the results of the three labs show an angular skewing: the first sample in Arizona dated to 1238, the second to 1430, with the Oxford and Swiss results falling in between. This corresponds to the angle of the seam that they detected. They add that the variance of the C-14 results of the labs falls outside the bounds of the Pearson's chi-square test, so that some additional explanation should be sought for the discrepency.

Such a repair, if it indeed occurred, would certainly skew the radiocarbon results. The site chosen was not a known repair site (of which there are many on the shroud). The results here stem from a single study, in any case, so that further study (and a repeated radiocarbon test from a known "clean" area of the shroud) would be necessary to make any definitive conclusions on the matter.

Material historical analysis

Much recent research has centered on the burn holes and water marks. The largest burns certainly date from the 1532 fire (another series of small round burns in an "L" shape seems to date from an undetermined earlier time), and it was assumed that the water marks were also from this event. However, in 2002, Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito presented a paper [6] at the IV Symposium Scientifique International in Paris stating that many of these marks stem from a much earlier time because the symmetries correspond more to the folding that would have been necessary to store the cloth in a clay jar (like cloth samples at Qumran) than to that necessary to store it in the reliquary that housed it in 1532.

According to master textile restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg of Hamburg, a seam in the cloth corresponds only to a fabric found at the fortress of Masada near the Dead Sea, which dated to the first century. The weaving pattern, a 3:1 twill, is consistent with first century Syrian design, according to the appraisal of Gilbert Raes of the Ghent Institute of Textile Technology in Belgium. Flury-Lemberg stated, "The linen cloth of the Shroud of Turin does not display any weaving or sewing techniques which would speak against its origin as a high-quality product of the textile workers of the first century."

Biological and medical forensics

Details of crucifixion technique

The piercing of the wrists rather than the palms goes against traditional Christian iconography, especially in the Middle Ages, but many modern scholars suggest that crucifixion victims were generally nailed through the wrists, and a skeleton discovered in the Holy Land shows that at least some were nailed between the radius and ulna; this was not common knowledge in the Middle Ages. Proponents of the shroud's mystical origins contend that a medieval forger would have been unlikely to know this operational detail of an execution method almost completely discontinued centuries earlier.

Blood stains

There are several reddish stains on the shroud suggesting blood. Chemist Walter McCrone (see above) identified these as simple pigment materials and reported that no forensic tests of the samples he used indicated the presence of blood. Other researchers, including Dr. Alan Adler, a chemist specializing in analysis of porphyrins, identified the reddish stains as type AB blood.

The particular shade of red of the supposed blood stains is also problematic. Normally, whole blood stains discolor relatively rapidly, turning to a black-brown color, while these stains in fact range from a true red to the more normal brown color. Supporters of the shroud counter that the stains were not from bleeding wounds, but from the liquid exuded by blood clots. In the case of severe trauma, as evidenced by the Man of the Shroud, this liquid would include a mixture of bilirubin and oxidized hemoglobin, which could remain red indefinitely. Adler and John Heller [7] detected bilirubin and the protein albumin in the stains. However, it is uncertain whether the blood stains were produced at the same time as the image, which Adler and Heller attributed to premature aging of the linen. (See Heller and Adler, 1980.)

Pollen grains

Researchers of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem reported the presence of pollen grains in the cloth samples, showing species appropriate to the spring in Palestine. However, these researchers, Avinoam Danin and Uri Baruch were working with samples provided by Max Frei, a Swiss police criminologist who had previously been censured for faking evidence. Independent review of the strands showed that one strand out of the 26 provided contained significantly more pollen than the others, perhaps pointing to deliberate contamination.

The Israeli researchers also detected the outlines of various flowering plants on the cloth, which they say would point to March or April and the environs of Jerusalem, based on the species identified. In the forehead area, corresponding to the crown of thorns if the image is genuine, they found traces of Gundelia tournefortii, which is limited to this period of the year in the Jerusalem area. This analysis depends on interpretation of various patterns on the shroud as representing particular plants. However, skeptics point out that the available images cannot be seen as unequivocal support of any particular plant species due to the amount of indistinctness.

Sudarium of Oviedo

In the northern Spanish city of Oviedo, there is a small bloodstained piece of linen that is also revered as one of the burial cloths mentioned in the Gospel of John. John refers to a "sudarium" (σουδαριον) that covered the head and the "linen cloth" or "bandages" (οθονιον—othonion) that covered the body. The sudarium of Oviedo is traditionally held to be this cloth that covered the head of Jesus.

The sudarium's existence and presence in Oviedo is well attested since the eighth century and in Spain since the seventh century. Before these dates the location of the sudarium is less certain, but some scholars trace it to Jerusalem in the first century.

Forensic analysis of the bloodstains on the shroud and the sudarium suggest that both cloths may have covered the same head at nearly the same time. Based on the bloodstain patterns, the Sudarium would have been placed on the man's head while he was in a vertical position, presumably while still hanging on the cross. This cloth was then presumably removed before the shroud was applied.

A 1999 study [8] by Mark Guscin, member of the multidisciplinary investigation team of the Spanish Center for Sindonology, investigated the relationship between the two cloths. Based on history, forensic pathology, blood chemistry (the Sudarium also is said to have type AB blood stains), and stain patterns, he concluded that the two cloths covered the same head at two distinct, but close moments of time. Avinoam Danin (see above) concurred with this analysis, adding that the pollen grains in the sudarium match those of the shroud.

Skeptics say that this argument is spurious. Since they deny the blood stains on the shroud, the blood stains on this cloth are irrelevant. Further, the argument about the pollen types is greatly weakened by the debunking of Danin's work on the shroud due to the possibly tampered-with sample he worked from. Pollen from Jerusalem could have followed any number of paths to find its way to the sudarium, and only indicates location, not the dating of the cloth. [9]

Digital image processing

Using techniques of digital image processing, several additional details have been reported by scholars.

NASA researchers Jackson, Jumper and Stephenson report detecting the impressions of coins placed on both eyes after a digital study in 1978. The coin on the right eye was reported to correspond to a Roman copper coin produced in AD 29 and 30 in Jerusalem, while that on the left resembles a lituus coin from the reign of Tiberius.

Piero Ugolotti reported (1979) Greek and Latin letters written near the face. These were further studied by André Marion and his student Anne Laure Courage of the Institut d'Optique Théorique et Aplliquée d'Orsay (1997). On the right side they cite the letters ΨΣ ΚΙΑ. They interpret this as ΟΨ—ops "face" + ΣΚΙΑ—skia "shadow", though the inital letter is missing. This interpretation has the problem that it is grammatically incorrect in Greek, as "face" would have to appear in the Genitive case. On the left side they report the Latin letters IN NECE, which they suggest is the beginning of IN NECEM IBIS, "you will go to death", and ΝΝΑΖΑΡΕΝΝΟΣ—NNAZARENNOS (a grossly misspelled "the Nazarene" in Greek). Several other "inscriptions" were detected by the scientists, but Mark Guscin [10] (himself a shroud proponent) reports that only one is at all probable in Greek or Latin: ΗΣΟΥ This is the genitive of "Jesus", but missing the first letter.

These claims are strongly rejected by skeptics, because there is no recorded Jewish tradition of putting coins over the eyes of the dead, and because of the spelling errors in the reported text. (Cf. Antonio Lombatti [11]) Guscin concurs with the skeptics who hold that these details are based on highly subjective impressions, much like the results of a Rorschach test.

Textual criticism

The Gospel of John is sometimes cited as evidence that the shroud is a hoax since English translations typically use the plural word "cloths" or "clothes" for the covering of the body: "Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and seeth the linen clothes [othonia] lie, and the napkin [sudarium], that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself" (Jn 20:6-7, KJV). Shroud proponents hold that the "linen clothes" refers to the Shroud of Turin, while the "napkin" refers to the Sudarium of Oviedo.

The Gospel of John also states, "Nicodemus ... brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about an hundred pound weight. Then took they the body of Jesus, and wound it in linen clothes with the spices, as the manner of the Jews is to bury" (Jn 19:39-40, KJV). No traces of spices have been found on the cloth. Frederick Zugibe, a medical examiner, reports[12] that the body of the man wrapped in the shroud appears to have been washed before the wrapping. It would seem odd for this to occur after the anointing, so some proponents have suggested that the shroud was a preliminary cloth that was then replaced before the anointing, because there was not enough time for the anointing due to the Sabbath. However, there is no empirical evidence to support these theories. Some supporters suggest that the plant bloom images detected by Danin may be from herbs that were simply strewn over the body due to the lack of preparation time mentioned in the New Testament, with the visit of the women on Sunday thus presumed to be for the purpose of completing the anointing of the body.

Analysis of artistic style

Many viewers of the cloth are struck by the anatomically correct depiction of the Man of the Shroud, which is often described as having a three-dimensional appearance. Since the presentation of perspective in two dimensional artwork was a relatively late development, some conclude that it could not have been a medieval forgery. Skeptics cite the great improvement brought about in early Renaissance masters.

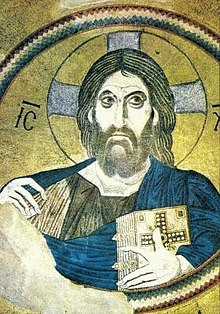

The depiction of Jesus corresponds to that found throughout the history of Christian iconography. For instance, the Pantocrator icon at Daphne in Athens is strikingly similar. Skeptics attribute this to the icons being made while the Image of Edessa was available, with this appearance Jesus being copied in later artwork, and in particular, in the Shroud. In opposition to this viewpoint, the locations of the piercing wounds in the wrists on the shroud do not correspond to artistic renditions of the crucifixion before close to the present time.

The Shroud in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, owners of the shroud, has made no pronouncements claiming it is Christ's burial shroud, or that it is not a forgery. The matter has been left to the personal decision of the faithful. Pope John Paul II stated in 1998, "Since we're not dealing with a matter of faith, the church can't pronounce itself on such questions. It entrusts to scientists the tasks of continuing to investigate, to reach adequate answers to the questions connected to this shroud." He has shown himself to be deeply moved by the image of the shroud, and arranged for public showings in 1998 and 2000.

As the image itself is a cause for prayer and meditation for many believers, even a definitive proof that the image does not date from the first century would likely not stem devotion to the object, which would then become something of an icon of the crucifixion. Pope John Paul II called the shroud "the icon of the suffering of the innocent of all times."

The Shroud was given to the Catholic Church by the House of Savoy in 1983. Some have suggested that if the identity of the Shroud with the Image of Edessa were to be definitively proven, the Church would have no moral right to retain it, and would then be compelled to return it to the Ecumenical Patriarch or some other Eastern Orthodox body, since it this case, it would have been stolen from the Orthodox at some time during the Crusades. Some Russian Orthodox consider that with the fall of Byzantium, the title of "emperor" passed on to Russia, so that they would have sole rights to the shroud over all the other Orthodox.

Conclusions

The carbon 14 dating, which was intended to settle the issue conclusively, and did so for many scientists, has not quelled speculation about the possible mystical origin of the shroud. Some scientists call for more radiocarbon tests of areas of the cloth containing the image, which the Holy See to date has refused. Given their expressed concerns about the destructive nature of current testing methods, it is unlikely that this resistance will change in the near future. Skeptics hold that the Vatican simply wants to avoid definite proof of forgery.

Devotion to the image of the Man of the Shroud has made argument about this issue particularly heated. Because of the deeply held beliefs touched by this piece of cloth, complete resolution of the issue may never be reached to the satisfaction of all parties.

References

- Guscin, Mark: "The 'Inscriptions' on the Shroud" British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, November 1999.

- Heller, J.H. and Adler, A.D.: "Blood on the Shroud of Turin" Applied Optics 19:2742-4 (1980).

- Humber, Thomas: The Sacred Shroud. New York: Pocket Books, 1980. ISBN 0671418890

- John Damascene: On Holy Images [13]

- Lombatti, Antonio: "Doubts Concerning the Coins over the Eyes" British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter, Issue 45, 1997.

- Nickell, Joe: "Scandals and Follies of the 'Holy Shroud'" Skeptical Inquirer, Sept. 2001. [14]

- Picknett, Lynn, and Prince, Clive: The Turin Shroud: In Whose Image?, Harper-Collins, 1994 ISBN 0552147826

- Rogers, R.N, and Arnoldi, A.: "The Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction (Maillard reaction) may explain the image formation". In Ames, J.M. (Ed.): Melanoidins in Food and Health, Volume 4, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2003, pp. 106-113.

- Zugibe, Frederick: "The Man of the Shroud was Washed" Sindon N. S. Quad. 1, June 1989.

External links

- Photos of the Shroud (text is in Italian)

- Discovery of image on reverse side of shroud (The Guardian)

Sites which claim the shroud is of natural or supernatural origin

- The Shroud of Turin Website An unofficial home website for the shroud.

- Speech by Pope John Paul about the shroud

- The Shroud of Turin Story — A Guide to the Facts

- The Shroud of Turin: Proof of the Resurrection A collection of essays and articles.

- "Shroud of Christ?" (A "Secrets of the Dead" episode on PBS)

- "The Shroud of Turin's 'Blood' Images: Blood, or Paint? A History of Science Inquiry"

Sites which claim the shroud is man-made or not associated with Christ

- The Skeptical Shroud of Turin Website Includes list of links (some now dead) for both viewpoints

- Skeptic's Dictionary: Shroud of Turin An encyclopedia-style article.

- McCrone Research Institute presentation of its findings Assertion that the shroud is a painting.

- Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal A summary of skeptical claims.