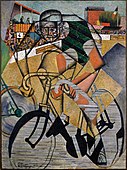

Soldier at a Game of Chess

| Soldat jouant aux échecs | |

|---|---|

| English: Soldier at a Game of Chess | |

| |

| Artist | Jean Metzinger |

| Year | c.1915 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 81.3 cm × 61 cm (32 in × 24 in) |

| Location | Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago. Gift of John L. Strauss, Jr. in memory of his father John L. Strauss, Accession No.: 1985.21, Chicago |

Soldier at a Game of Chess (in French Soldat jouant aux échecs, or Le Soldat à la partie d'échecs), is a painting by the French artist Jean Metzinger. While serving as a medical orderly in Sainte-Menehould, France, during World War I, Metzinger bore witness to the ravages of war firsthand. Rather than depicting such horrors, Metzinger, an outspoken pacifist, chose to represent a poilus sitting at a game of chess, peacefully smoking a cigarette. Even so, the military subject of this painting, possibly a self-portrait, raises questions much discussed in the French wartime press about how modern warfare should be represented.

During the month of March 1915, Metzinger was called to serve the military,[1] and was invalided out of service later that year.[2] Soldier at a Game of Chess was painted during his mobilization.[3] This, along with stylistic considerations, situates the date of the painting as 1915.[4]

This distilled form of Cubism, soon to be known as Crystal Cubism, is consistent with Metzinger's shift, between 1915 and 1916, towards a strong emphasis on large, flat surface activity, with overlapping geometric planes. The manifest primacy of the underlying architectonic anatomy of the composition, entrenched in the abstract, controls practically all of the elements of the painting. Color remains primordial but is moderate and sharply delineated by boundary conditions.[5]

The painting—a gift of John L. Strauss, Jr. in memory of his father John L. Strauss—forms part of the permanent collection at the Smart Museum of Art, located on the campus of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois.[6]

Description

Soldier at a Game of Chess, initialed "JM" and signed "JMetzinger" (lower right), is an oil painting on canvas with dimensions 81.3 x 61 cm (32 x 24 in.). The vertical composition is painted in a geometrically advanced Cubist style, representing a solitary French soldier playing a game of chess. He wears a military hat (kepi) and bears a cigarette in his mouth. For the latter reason, it has been suggested by Joann Moser that this may be a self-portrait. Indeed, images of Metzinger invariably depicted him with a cigarette in his mouth: Robert Delaunay's 1906 Portrait of Metzinger (Man with a Tulip); Suzanne Phocas, Portrait de Metzinger, 1926.[5][7][8][9]

The soldier appears in an interplay of transparencies typical of Metzinger's earlier works. His head and hat are seen in both frontal side views simultaneously. His facial features are eminently stylized, simple, geometric, resting on rounded shoulders delineated by a rectangular structure superimposed with elemental monochromatic planes that compose the background. Depth of field is practically nonexistent. Blues, reds, green and black dominate the composition. The table—treated in faux bois, or trompe-l'œil—and the chessboard are practically seen from above, while the chess pieces are observed from the side; his right hand is fused within.

Direct reference to observed reality is present, but the emphasis is placed on the self-sufficiency of the painting as an object unto itself. Orderly qualities and the autonomous purity of the composition are a prime concern.[10]

The overall composition is highly crystalline in its geometricized materialization, consisting of superimposed synthetic planes; something Albert Gleizes would later refer to, in La Peinture et ses lois (1922), as 'simultaneous movements of translation and rotation of the plane'.[11] Gleizes too had been working along similar lines during his mobilization at Toul, where he painted Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portrait d'un médecin militaire), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[12] The synthetic factor was ultimately taken furthest of all from within the Cubists by Gleizes.[13]

Mobilization

The number 24 on the soldiers collar represents the fr. It is unclear whether or not Metzinger formed part of the 24th regiment, but he certainly would have seen wounded soldiers from the 24th, as they had participated in a brutal offensive on 25 May 1915 in Aix-Noulette, where contact with a bitter enemy caused unusually heavy losses. Metzinger had been stationed further south of the devastated area. The town of Sainte-Menehould became an important location during the conflict. Located south of the Argonne Forest, Sainte-Menehould became a command and control center of Marne; with primary medical care facilities, food provisions and resting facilities for many units fighting in the region. In a constant crossover of men and materials, army photographers shot dozens of clichés during the summer of 1915, reflecting the strategic importance of this town.[14]

From January 1915, St. Menehould was the command post of the IIIe armée française under General Maurice Sarrail. The city suffered its first bombing campaign by canon the same year. Thereafter, aircraft and zeppelins took over the skies. In September 1915 the successful counter-offensive moved the front closer to the German border.[15]

Crystal Cubism

The Cubist considerations manifested prior to the outset of World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been vacated, replaced by a purely formal reference frame.[10]

This clarity and sense of order spread to almost all on the artists under contract with Léonce Rosenberg—including Metzinger, Juan Gris, Jacques Lipchitz, Henry Laurens, Auguste Herbin, Joseph Csaky and Gino Severini—leading to the descriptive term 'Crystal Cubism', coined by the critic fr.[10]

Even before Raynal coined the term Crystal Cubism, one critic by the name of Aloës Duarvel, writing in L'Elan, referred to Metzinger's entry exhibited at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune as 'jewellery' ("joaillerie").[16] Another critic, Aurel, writing in L'Homme Enchaîné about the same December 1915 exhibition described Metzinger's entry as "a very erudite divagation of horizon blue and old red of glory, in the name of which I forgive him" [une divagation fort érudite en bleu horizon et vieux rouge de gloire, au nom de quoi je lui pardonne].[17]

By its very date of execution, Metzinger's Soldier at a Game of Chess was precursor to a style that would become known as Crystal Cubism.[11][13][18]

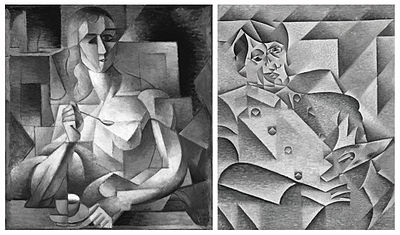

It is interesting to compare Soldier at a Game of Chess not just with other works by Metzinger, such as Femme au miroir, painted shortly after (see below), but to those of his colleague and friend Juan Gris, also of the Crystal Cubist style, who's Portrait of Josette Gris was painted several months after Metzinger's canvas, and with Seated Woman of 1917, also by Gris, painted the following year.

All three are examples of Crystal Cubism: the three works employ transparencies that blur the distinction between the background and the figure. Rather than gradients of tone or color, the three are painted with flat, uniform sections of tone and color, allbeit Metzinger uses a textured surface to simulate grain in the wooden table, and some minimal brush-strokes as visible in the three. Each represents objects or elements of the real world; Metzinger, the chessboard, a soldier, Gris, the moulding of the wall, an earing, a woman. Most outstanding of all in these three works, however, is the primacy of the manifest geometric manifold, the angular juxtaposition of the surface planes, consistent with a process of distillation otherwise auxiliary before the war.

During the year 1916, Sunday discussions at the studio of Jacques Lipchitz, included Metzinger, Gris, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Reverdy, André Salmon, Max Jacob, and Blaise Cendrars.[19] Metzinger and Gris were thus in close contact.

In a letter written in Paris by Metzinger to Albert Gleizes in Barcelona during the war, dated 4 July 1916, he writes:

After two years of study I have succeeded in establishing the basis of this new perspective I have talked about so much. It is not the materialist perspective of Gris, nor the romantic perspective of Picasso. It is rather a metaphysical perspective—I take full responsibility for the word. You can't begin to imagine what I've found out since the beginning of the war, working outside painting but for painting. The geometry of the fourth space has no more secret for me. Previously I only had only intuitions, now I have certainty. I have made a whole series of theorems on the laws of displacement [déplacement], of reversal [retournement] etc. I have read Schoute, Rieman (sic), Argand, Schlegel etc.

The actual result? A new harmony. Don't take this word harmony in its ordinary [banal] everyday sense, take it in its original [primitif] sense. Everything is number. The mind [esprit] hates what cannot be measured: it must be reduced and made comprehensible.

That is the secret. There in nothing more to it [pas de reste à l'opération]. Painting, sculpture, music, architecture, lasting art is never anything more than a mathematical expression of the relations that exist between the internal and the external, the self [le moi] and the world. (Metzinger, 4 July 1916)[19][20]

The 'new perspective' according to Daniel Robbins, "was a mathematical relationship between the ideas in his mind and the exterior world".[19] The 'fourth space' for Metzinger was the space of the mind.[19]

In a second letter to Gleizes, dated 26 July 1916, Metzinger writes:

If painting was an end in itself it would enter into the category of the minor arts which appeal only to physical pleasure... No. Painting is a language—and it has its syntax and its laws. To shake up that framework a bit to give more strength or life to what you want to say, that isn't just a right, it's a duty; but you must never lose sight of the End. The End, however, isn't the subject, nor the object, nor even the picture—the End, it is the idea. (Metzinger, 26 July 1916)[19]

Continuing, Metzinger mentions the differences between himself and Juan Gris:

Someone from whom I feel ever more distant is Juan Gris. I admire him but I cannot understand why he wears himself out with decomposing objects. Myself, I am advancing towards synthetic unity and I don't analyze any more. I take from things what seems to me to have meaning and be most suitable to express my thought. I want to be direct, like Voltaire. No more metaphors. Ah those stuffed tomatoes of all the St-Pol-Roux of painting.[19][20]

Some of the ideas expressed in these letters to Gleizes were reproduced in an article written by Paul Dermée, published in the magazine SIC in 1919,[21] but the existence of letters themselves remained unknown until the mid-1980s.[19]

From 1916, Lipchitz, Gris and Metzinger had been in close contact with one another.[13] The three had just signed contracts with the dealer, art collector and gallery owner Léonce Rosenberg. It is the work of these three artists, executed during the war, that can be analyzed as a process of distillation in a shift towards order and purity. This process would continue through 1918 when the three spent part of the summer together in Beaulieu-Prés-Loches to escape the bombardment of Paris.[13]

At an opening held at the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris, on 9 June 1947, Léonce Rosenberg related his impressions to Hélène Bauret:

In the painting "La Tricoteuse",[22] hanging next to works by Gris, Metzinger reveals himself more of a painter, more natural, more flexible [plus souple] than Gris. Often, Gris would tell me: "Ah! If I could brush [brosser] like the French!"

Gris was indeed capable of producing works closely attuned to those of Metzinger. His late arrival on the Cubist scene (1912) saw him influenced by the leaders of the movement: Picasso, of the 'Gallery Cubists' and Metzinger of the 'Salon Cubists'.[23] His entry at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, Hommage à Pablo Picasso, was also an homage to Metzinger's Le goûter (Tea Time). Le goûter persuaded Gris of the importance of mathematics (numbers) in painting.[24]

As art historian Peter Brooke points out, Gris started painting persistently in 1911 and first exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants (a painting entitled Hommage à Pablo Picasso). "He appears with two styles", writes Brooke, "In one of them a grid structure appears that is clearly reminiscent of the Goûter and of Metzinger's later work in 1912. In the other, the grid is still present but the lines are not stated and their continuity is broken".[25]

Art historian Christopher Green writes that the "deformations of lines" allowed by mobile perspective in the head of Metzinger's Tea-time and Gleizes's Portrait of Jacques Nayral "have seemed tentative to historians of Cubism. In 1911, as the key area of likeness and unlikeness, they more than anything released the laughter." Green continues, "This was the wider context of Gris's decision at the Indépendants of 1912 to make his debut with a Homage to Pablo Picasso, which was a portrait, and to do so with a portrait that responded to Picasso's portraits of 1910 through the intermediary of Metzinger's Tea-time.[26]

While Metzinger's process of distillation is already noticeable during the latter half of 1915, and conspicuously extending into early 1916, this shift is signaled in the works of Gris and Lipchitz from the latter half of 1916, and particularly between 1917 and 1918.[13]

Kahnweiler dated the shift in style of Juan Gris to the summer and autumn of 1916, following the pointilliste paintings of early 1916.[27] This timescale corresponds with the period after which Gris signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg, following a rally of support by Henri Laurens, Lipchitz and Metzinger.[28]

Metzinger's radical geometrization of form as an underlying architectural basis for his 1915-16 compositions is already visible in his work circa 1912-13, in paintings such as Au Vélodrome (1912) and Le Fumeur (1913). Where before, the perception of depth had been greatly reduced, now, the depth of field was no greater than a bas-relief.[13]

Metzinger's evolution toward synthesis has its origins in the configuration of flat squares, trapezoidal and rectangular planes that overlap and interweave, a "new perspective" in accord with the "laws of displacement". In the case of Le Fumeur Metzinger filled in these simple shapes with gradations of color, wallpaper-like patterns and rhythmic curves. So too in Au Vélodrome. But the underlying armature upon which all is built is palpable. Vacating these non-essential features would lead Metzinger on a path towards Soldier at a Game of Chess, and a host of other works created after the artist's demobilization as a medical orderly during the war, such as L'infirmière (The Nurse) location unknown; Femme au miroir, private collection; Landscape with Open Window (1915)[29] Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes; Femme à la dentelle (1916) Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Summer (1916)[30] Statens Museum for Kunst; Le goûter (1917)[31] Galerie Daniel Malingue; Tête de femme (1916–17) private collection; Femme devant le miroir (c. 1914) private collection; Femme au miroir (1916–17) Donn Shapiro collection; Maison cubistes au bord de l'eau (1916);[32] and Femme et paysage à l'aqueduc (1916).[33]

If the beauty of a painting solely depends on its pictorial qualities: only retaining certain elements, those that seem to suit our need for expression, then with these elements, building a new object, an object which we can adapt to the surface of the painting without subterfuge. If that object looks like something known, I take it increasingly for something of no use. For me it is enough for it to be "well done", to have a perfect accord between the parts and the whole. (Jean Metzinger, quoted in Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920)[34]

Wartime and after

Healing the wound of the psyche that nurtures the talent of an artist, would destroy his artistic production (Jean Metzinger)[35]

Following the declaration of war in August 1914, many artists were mobilized, almost simultaneously: Metzinger, Gleizes, Braque, Léger, de La Fresnaye, Georges Valmier and Duchamp-Villon.[13] Each found the space and time to make art, sustaining differing types of Cubism (primarily sketches) during the war years. They discovered a ubiquitous link between the Cubist syntax (beyond pre-war attitudes) and that of the novelty and anonymity of mechanized warfare.[13] Cubism evolved as much a result of an evasion of the inconceivable atrocities of war as of nationalistic pressures. Along with the evasion came the need to diverge further and further away from the depiction of things.[13] As the rift between art and life grew, so too the came the burgeoning need for a process of distillation. Following the armistice and the series of exhibitions at Galerie de L'Effort Moderne, the rift between art and life—and the overt distillation that came with it—had become the canon of Cubist orthodoxy; and it would persist with the peace that followed.[13]

Metzinger served very close to the front during World War I, and was probably with his surgical automobile when Soldier at a Game of Chess was painted.[4] Very few of his works represent scenes associated with war. And rather than delving into the actual carnage of war, this painting evokes an idealized theory of war. The irony is that Metzinger came from a family of prominent military figures: his great-grandfather, Nicolas Metzinger (18 May 1769 – 1838),[36] Captain in the 1st Horse Artillery Regiment, and Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, had served under Napoleon Bonaparte.[37] Yet Jean Metzinger objected to active service during the war on conscientious grounds. Sent to the front as a medical aide, he witnessed the horrors of the conflict firsthand, yet the grim reality of war is virtually absent from this painting, and from others of the period. Instead, his interest is captured by mathematical rationality, order, his faith in humanity and modernity.[3][33] The war, however, is very present in this work, by the presence of the soldier, the anonymity of the sitter uniquely identified by the number of the 24th Regiment on his military uniform, and by the stereoscopic view of chess as simultaneously an intellectual game and a ruthless battle.[3] Chess players and theoreticians have long debated whether, given perfect play by both sides, the game should end in a win for White, or a draw. Since approximately 1889, when World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz addressed this issue, the overwhelming consensus has been that a perfectly played game would end in a draw: in "perfect accord between the parts and the whole" (again, in Metzinger's words).

The sculptures of Lipchitz, Laurens and Csaky, and the paintings of Gris, Severini and Gleizes represented Cubism in it's most distilled form between 1916 and 1920. However, by the time his exhibition at the Galerie de L'Effort Moderne at the outset of 1919—just as before the war—Metzinger was considered one of the leaders of the movement. His paintings at this exhibition were perceived as highly significant.[19][13] Images were now created solely out of the imagination of the artist (or virtually so), independent of any visual starting point. Observed reality and all that is referred to in life are no longer needed as foundation for artistic production. The synthetic manipulation of abstract geometric shapes, or "mathematical expression of the relations that exist between the le moi and the world" (in Metzinger's words), was the ideal metaphysical starting point. Only afterwards would those structures be made to denote objects of predilection.[19][13]

Metzinger acknowledges the irony of war in his choice of subject matter. The soldier plays an abstract strategy game in which the soldier himself is one of the pawns. Whatever the strategy of the soldier, his existence is adroitly dependent on non-deterministic results of his tactical decisions. His role is to minimize luck and the apparition of undesirable possibilities (such as may occur when cards are shuffled or when dice are rolled). As J. Mark Thompson wrote in his article "Defining the Abstract":

There is an intimate relationship between such games and puzzles: every board position presents the player with the puzzle, What is the best move?, which in theory could be solved by logic alone. A good abstract game can therefore be thought of as a "family" of potentially interesting logic puzzles, and the play consists of each player posing such a puzzle to the other. Good players are the ones who find the most difficult puzzles to present to their opponents.[38][39][40][41]

Indeed, the wartime distillation of Metzinger's Cubism came with an acceleration in the type of games that could be played tactically with paradox by manipulating conflicting predications of planimetric flatness and the perspectival depth of space. This game playing would culminate between 1917 and 1919, but is already palpable in Soldier at a Game of Chess. The perspectival presentation is only fragmentary—almost non-Cubist in abstract guise—and lacks coherence, so that the resulting composition is throughout paradoxical. There are sufficient indications to suggest a soldier and the activity in which he's engaged; his military cap (and an echo of it in red), a hand (however transparent it may be), a face (with a cigarette in its mouth), the alternating colored squares of a chessboard, a rook, a pawn and other chess pieces. But the figure and his setting simultaneously fuse as an arrangement of planes that cancel those indications of depth any greater than a relief. And the disorientations are compounded by Metzinger's placing of green and orange in the soldiers upward-turned face, while the red of his arms espouse the echo-like profile of the face and cap in the background plane directed downward toward the game, for it becomes almost inevitable to see the soldiers alter ego; an effect that both pulls the man into the background of the composition and pushes him forward towards the viewer, again, canceling out indications of depth.

Here, Metzinger uses a checkerboard and wooden table to establish a clearly demarcated fore-plane that is non-fixed in relation to which its 'hovering' chess pieces are situated. This profound battle between planimetric and perspectival dimensions as here in Soldier at a Game of Chess has precedence in Metzinger's Cubism of 1912-13, but the absence of decorative elements, the clarity and sense of order, and degree of game-playing with conflicting codes for the personification of space that he refined during the war places the artist at the forefront of the nascent form of art dubbed Crystal Cubism by the critic fr.[10][19][13][42]

Exhibitions and reproductions

JAMA

On 26 May 1993 Soldier at a Game of Chess was reproduced on the cover of JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association, a peer-reviewed medical journal published by the American Medical Association covering all aspects of the biomedical sciences.[43]

From 1964 to 2013 the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published full color images of artwork on its cover, accompanied by essays inside the journal. JAMA's former editor, George Lundberg, wrote that this was part of an initiative to inform readers about nonclinical aspects of medicine and public health, and to emphasize the link between the humanities and medical science.[44]

M. Therese Southgate served as Cover Editor of JAMA for over 30 years, choosing the images and writing commentary on the artworks. In an essay on her philosophy of art and medicine she wrote:

Medicine is itself an art. It is an art of doing, and if that is so, it must employ the finest tools available—not just the finest in science and technology, but the finest in the knowledge, skills, and character of the physician. Truly, medicine, like art, is a calling.

And so I return to the question I asked at the beginning. What has medicine to do with art?

I answer: Everything.[44]

Another work by Metzinger titled The Lamp (1917) was reproduced on the cover of JAMA on 27 September 2006 (Vol. 296 Issue 12).[45]

In 2011 Soldier at a Game of Chess was featured on the cover of The Art of JAMA: Covers and Essays from The Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 3, with the 1993 essay by Southgate reproduced in the edition.[4]

Musée de Lodève

From 22 June to 3 November 2013 the fr, called Musée de Lodève (Hérault), explored the evolution of Cubism through an exhibition entitled Gleizes - Metzinger, du cubisme et après: a continuation of an exhibition in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of Du "Cubisme" by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, held at the Musée de La Poste in Paris.[46] Prior to the exhibition, the Musée de Lodève successfully launched a fund raising campaign to help finance the sending of Metzinger's Soldat jouant aux échecs (Soldier at a Game of Chess) from the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago to Lodève.[3][47][48]

Imaging/Imagining

For the occasion of an exhibition titled Imaging/Imagining the Human Body in Anatomical Representation, March 25–June 20, 2014 at the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Soldier at a Game of Chess was exhibited along side an X-ray composite based on Metzinger's painting. The composite was produced by Adam Schwertner (fourth year medical student at the Pritzker School of Medicine, The University of Chicago), Stephen Thomas, MD (Assistant Professor of Radiology), and Brian Callender, MD (Assistant Professor of Medicine). Digitally assembled radiographic images provided by the Department of Radiology at the University of Chicago Medical Center were superimposed on an image of the painting.

Imaging/Imagining was curated by Brian Callender, MD, and Mindy Schwartz, MD, Professor of Medicine at the University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Medicine, in consultation with Anne Leonard, Smart Museum Curator and Associate Director of Academic Initiatives. It was presented by the Special Collections Research Center, Smart Museum of Art, and the John Crerar Library in collaboration with the University of Chicago Arts|Science Initiative/Office of the Provost at the University of Chicago. The exhibition was free and open to the public.

The exhibition was a three-venue exhibition at the University of Chicago that brought to light the interdependence between representations of human anatomy of biomedicine's imaging technology and imaginings in the creative art's. Visitor's encountered whole-body images of the human vascular system from Govert Bidloo's 1685 anatomical atlas, Anatomia Humani Corporis, a man-shaped map of rivers and tributaries, or trees feathering out from a central trunk—with a heart at its core. A digital composite generated for the exhibition of an eye and pen (and cadaver) was made out of data-sourced from CT angiograms. Both are medical representations of the anatomy of the vascular system, yet their context in the exhibition gives the allure of artworks.[49]

The exhibition's curators, physicians Brian Callender and Mindy Schwartz from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, employed a wide range of images and objects and set them resonating against each other in order to challenge the viewer to find, and to make connections between historical periods, disciplines, the exhibited objects and the viewer's own embodied relationship between to them: such as a collage of X-rays on a gallery wall beside Metzinger's Soldier at a Game of Chess, analyzed for its anatomical information. Also in the exhibition, a nude by Henry Moore along side a series of 19th-century diagrams of the heart in multiple perspectives right through to its black-and-white bones, the nude's gaps suggestive signs of an aortic arch, a septum, valves.[49]

Depicting the body has been essential to practitioners of both art and medicine for centuries. While medical doctors have long relied on anatomical illustrations to understand what goes on inside the body, drawing the human form has been a fundamental component of art pedagogy. The advent of advanced imaging technology now allows us to see structures and processes that were inaccessible to the eye, taking away the artist's "hand" and reducing the role of subjective imagination.[50]

Following the early death of his father, Eugène François Metzinger, Jean pursued interests in mathematics, music and painting, though his mother, a music professor by the name of Eugénie Louise Argoud, had ambitions of his becoming a medical doctor.[51]

Organized by physicians, this exhibition gathered images of the body from a range of historical periods and considered "the extent to which they conform to established representational conventions or seem instead to reflect the artist's own observations or expressive goals".[50] "Other themes considered were the enduring role of figure drawing in academic art study; the relation between artistic and scientific abstraction; the depiction of bodily suffering in wartime; and what art and medicine have to offer each other in the pursuit of accuracy, humanity, and empathy, when it comes to representing the body".[50]

Metzinger was fascinated by the ability of X-rays to reveal the unseen, "in which case he may have liked this modern interpretation of his painting".[52] One year before Metzinger painted Soldier at a Game of Chess, the German physicist Max von Laue won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals.[53][54][55] Of interest to the Cubists, in addition to new scientific discoveries such as Röntgen's X-rays and Laue's X-ray diffraction, were Hertzian electromagnetic radiation and radio waves propagating through space, revealing realities not only hidden from human observation, but beyond the sphere of sensory perception. Perception was no longer associated solely with the static, passive receipt of visible signals, but became dynamically shaped by perceptual learning, memory and expectation.[56][57][58]

Related works

-

Jean Metzinger, 1912, At the Cycle-Race Track (Au Vélodrome), oil and sand on canvas, 130.4 x 97.1 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

-

Jean Metzinger, 1912-1913, L'Oiseau bleu, (The Blue Bird), oil on canvas, 230 x 196 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

-

Albert Gleizes, 1914, Woman with animals (La dame aux bêtes) Madame Raymond Duchamp-Villon, oil on canvas, 196.4 x 114.1 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

-

Juan Gris, 1915, Still Life before an Open Window, Place Ravignan, oil on canvas, 115.9 x 88.9 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Juan Gris, September 1915, Jeu d'échecs (The Checkerboard), oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

-

Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Femme à sa toilette, Lady at her Dressing Table), oil on canvas, 92.4 x 65.1 cm, private collection

-

Diego Rivera, after August 1916, Maternidad, Angelina y et niño Diego (Motherhood, Angelina and the Child Diego), oil on canvas, 134.5 x 88.5 cm, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City

-

Jean Metzinger, 1916, Fruit and a Jug on a Table, oil and sand on canvas, 115.9 x 81 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-

Diego Rivera, 1916, Seated Woman (Woman with the Body of a Guitar), Frida Kahlo Museum

-

Juan Gris, 1917, Glass and Water Bottle, oil on panel, 54.8 x 32.7 cm, Ohara Museum of Art

-

Pablo Picasso, 1917, Arlequin (Harlequin)

-

María Blanchard, 1916–18, Still Life with Red Lamp, oil on canvas, 115.6 × 73 cm

-

Juan Gris, 1917, Harlequin with a Guitar, oil on panel, 101 × 65.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Georges Braque, 1917, La Joueuse de mandoline, oil on canvas, 92 × 65 cm, Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art

-

Pablo Picasso, 1918, Arlequin au violon (Harlequin with Violin), oil on canvas, 142 x 100.3 cm, Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

-

Gino Severini, 1919, Bohémien Jouant de L'Accordéon (The Accordion Player), Museo del Novecento, Milan

-

Louis Marcoussis, 1919, Violon, bouteilles de Marc et cartes (Violin, Marc bottles and cards), gouache and watercolor over charcoal on paper, 45.8 x 24.5 cm

-

Albert Gleizes, 1920, Femme au gant noir (Woman with Black Glove, Femme assise), oil on canvas, 126 x 100 cm, private collection

-

Alexander Archipenko, c.1920, Femme assise (Composition), 31.1 x 23.2 cm, gouache on paper

-

Joseph Csaky, Deux figures, 1920, relief, limestone, polychrome, 80 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

References

- ^ L'Intransigeant, La Boîte aux Lettres, 23 March 1915, p. 2

- ^ Larousse, Dictionaire de la peinture, Jean Metzinger

- ^ a b c d Soldat jouant aux échecs : un portrait cubiste magistral, Musée de Lodève

- ^ a b c d e The Art of JAMA: Covers and Essays from The Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 3, M. Therese Southgate, Oxford University Press, Mar 17, 2011

- ^ a b Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Cubist works, 1910–1921, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press 1985, pp. 44, 45

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1915, Soldier at a Game of Chess (Soldat jouant aux échecs), oil on canvas, 81.3 x 61 cm, Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago

- ^ Daniel Robbins, Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press 1985

- ^ Suzanne Phocas, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz

- ^ Restauration du « Portrait de Jean Metzinger » par Suzanne Phocas, INP, Institut national de patrimoine, Médiathèque Numérique

- ^ a b c d Christopher Green, Late Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ a b Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes: For and Against the Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0300089643

- ^ Albert Gleizes, 1914-15, Portrait of an Army Doctor (Portrait d'un médecin militaire), oil on canvas, 119.8 x 95.1 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13-47, 215

- ^ La Marne et la Grande Guerre dans les collections photographiques et cinématographiques de l’ECPAD, Les archives de la SPCA sur la Marne, 1915-1919

- ^ L'Histoire, consulté le 24 janvier 2011.

- ^ La Tombola artistique au profit des artistes polonais victimes de la guerre, 28 décembre 1915 au 15 janvier 1916, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, 25, boulevard de la Madeleine, published in L'Elan, Number 8, January 1916

- ^ Échos, 1915 et la peinture, L'Homme Enchaîné, Paris, A3, No. 455, Saturday, 8 January 1916 (front page)

- ^ H. Harvard Arnason, History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography, edited by Peter Kalb, Pub. Prentice Hall, 2004, ISBN 013184105X

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, pp. 9–24

- ^ a b Peter Brooke, Higher Geometries, Precedents: Charles Henry and Peter Lenz, The subjective experience of space, Metzinger, Gris and Maurice Princet

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Une Esthétique, by Paul Dermée, SIC, Volume 4, Nos. 42, 43, March 30 and April 15, 1919, p. 336

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Tricoteuse, Dépôt du Centre Pompidou, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, Agence Photographique de la Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées

- ^ John Golding, Visions of the Modern, University of California Press, 1994, ISBN 0520087925

- ^ John Richardson: A Life of Picasso, volume II, 1907–1917, The Painter of Modern Life, Jonathan Cape, London, 1996, p. 211

- ^ Peter Brooke, On "Cubism" in context, online since 2012

- ^ Christopher Green, Christian Derouet, Karin Von Maur, Juan Gris: [catalogue of the Exhibition], 1992, London and Otterlo, p. 160

- ^ Christian Derouet, Karin von Maur, Juan Gris, Withechapel Art Gallery, London, 18 September -29 November 1992, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 18 December 1992 - 14 February 1993, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, 6 March - 2 May 1993, Yale University Press, 1992, ISBN 0300053746

- ^ Christian Derouet, Le cubisme «bleu horizon» ou le prix de la guerre. Correspondance de Juan Gris et de Léonce Rosenberg -1915-1917, Revue de l'Art, 1996, Vol. 113, Issue 113, pp. 40-64

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Landscape with Open Window, signed and dated JMetzinger 1915, oil on canvas, 73 × 54 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes (Artsy)

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1916, Summer (Sommeren), oil on canvas, 74.5 x 55.5 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1917, Le goûter, oil on canvas, 92 x 67 cm, Galerie Daniel Malingue, Paris

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1916, Maison cubistes au bord de l'eau, oil on canvas, 73.03 x 59.99 cm, private collection (MutualArt)

- ^ a b Jean Metzinger, 1916, Femme et paysage à l'aqueduc (Woman and landscape with an aqueduct), oil and sand on canvas, 73 x 54 cm (28 ¾ x 21 ¼ in.), Christie's Paris, 2 May 2012, lot 23, est 400,000-600,000 EUR, sold 937,000 EUR

- ^ Jean Metzinger, quoted in Au temps des Cubistes, 1910-1920, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galerie Berès, 2006, p. 432. Reproduced in Christie's Paris, 2 May 2012, Lot 23 notes

- ^ Dracoulides N, N, Créativité de l'artiste psychanalysé. Psychother Psychosom 1964;12:391-401\, Published online: February 11, 2010, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Vol. 12, No. 5-6, Year 1964 (Cover Date: 1964), Journal Editor: Fava G.A. (Bologna), ISSN: 0033-3190 (Print), eISSN: 1423-0348 (Online)

- ^ Royal Ancestry file, Jean Metzinger family members

- ^ Leonore, culture.gouv.fr database, Nicolas Metzinger

- ^ Thompson, J. Mark. (2000, July) Defining the Abstract. The Games Journal. Retrieved April 2, 2010

- ^ International Abstract Games Organisation article on game genres, Retrieved September 10, 2010

- ^ "Abstract Strategy Games". Random knowledge. 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- ^ "Glossary". BoardGameGeek. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alex Mittelmann, 2012, Jean Metzinger, Divisionism, Cubism, Neoclassicism and Post Cubism

- ^ JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association, M. Therese Southgate, MD, May 26, 1993, Vol 269, No. 20, cover: Jean Metzinger, Soldier at a Game of Chess

- ^ a b Jefferey M. Levine, MD, JAMA removes cover art, and why that matters, November 6, 2013

- ^ JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association, M. Therese Southgate, MD, 27 September 2006 (Vol. 296 Issue 12, cover: Jean Metzinger, The Lamp

- ^ Gleizes - Metzinger. Du Cubisme et après, 9 May - 22 September 2012, Musée de La Poste, Galerie du Messager, Paris, France. Exposition in commemoration of 100th anniversary of the publication of Du "Cubisme"

- ^ Le Musée de Lodève vous tient à coeur ? Devenez mécène de la prochaine exposition d'été ! Donation request for exhibiting Jean Metzinger, 1915, Le Soldat à la partie d'échecs (Soldier at a Game of Chess)

- ^ Arrêté du 20 février 2013 relatif à l'insaisissabilité de biens culturels, JORF n°0048 du 26 février 2013 page 3206, texte n° 19. Jean Metzinger, Le Soldat à la partie d'échecs, and Albert Gleizes, 1917, Dans le port, Musée Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

- ^ a b Imaging/Imagining the Human Body in Anatomical Representation, The University of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art

- ^ a b c Imaging/Imagining: The Body as Art, The Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, March 25 – June 22, 2014

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1883-1956: exposition, Nantes, École des beaux-arts, Atelier sur l'herbe, 4 au 26 janvier 1985

- ^ How to Take Photos in a Museum, Christina, 19 January 2015

- ^ Hentschel, 1996, Appendix F, see entry for Max von Laue.

- ^ Max von Laue Biography – Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin

- ^ Ewald, P. P. (ed.) 50 Years of X-Ray Diffraction (Reprinted in pdf format for the IUCr XVIII Congress, Glasgow, Scotland, International Union of Crystallography). Ch. 4, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Mark Antliff, Patricia Dee Leighten, Cubism and Culture, Thames & Hudson, 2001

- ^ Gregory, R., "Perception" in Zangwill, O. and Gregory, R. (eds) The Oxford Companion to the Mind, 1987, ISBN 0-19-866124-X, pp. 598–601

- ^ Linda D. Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean geometry in Modern Art, Princeton University Press, 1983