Čelebići camp

| Čelebići prison camp | |

|---|---|

| Detainment camp | |

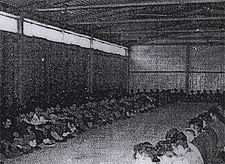

Serbs from the Konjic area detained in the Čelebići camp | |

| Location | Čelebići, Konjic municipality, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Operated by | Bosnian Ministry of the Interior, Croatian Defence Council, Bosnian Territorial Defence |

| Operational | May–December 1992 |

| Inmates | Bosnian Serbs |

| Number of inmates | 400–700 |

| Killed | 13–30 |

The Čelebići camp was a prison camp run by Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces during the Bosnian War.[1] It was used by several units of the Bosnian Ministry of the Interior (MUP), Croatian Defence Council (HVO) and later the Bosnian Territorial Defence Forces (TO). The camp was located in Čelebići, a village in the central Bosnian municipality of Konjic.[2]

The camp, operational from May to December 1992, was used to detain Bosnian Serb prisoners of war, most of whom were civilians[2][3] arrested during military operations that were intended to de-block routes to Sarajevo and Mostar in May 1992 that had earlier been blocked by Serb forces.[2] The exact number of prisoners that were held at the camp is unknown but estimates range between 400 and 700.[4][5][6]

Detainees at the camp were subjected to torture, sexual assaults, beatings and otherwise cruel and inhuman treatment.[7] Certain prisoners were shot and killed or beaten to death. Investigators believe that as many as 30 died while in captivity.[8] However, the ICTY's indictment only listed the deaths of 13 people.[6]

Hazim Delić, Esad Landžo, Zejnil Delalić and Zdravko Mucić were indicted for their roles in the crimes committed at the camp. All were found guilty, except for Delalić.[7][9] In reaching its decision, the ICTY made a landmark judgement by qualifying rape as a form of torture, the first such judgement by an international criminal tribunal.[10]

Background

During the conflict in Yugoslavia, Konjic municipality was of strategic importance as it contained important communication links from Sarajevo to southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. During the Siege of Sarajevo the route through Konjic was of vital importance to the Bosnian government forces.[11] Furthermore, several important military facilities were contained in Konjic, including the Igman arms and ammunition factory, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) Ljuta barracks, the Reserve Command Site of the JNA, the Zlatar communications and telecommunications centre, and the Celebici barracks and warehouses.

Although the Konjic municipality did not have a majority Serb population and did not form part of the declared "Serb autonomous regions", in March 1992, the self-styled "Serb Konjic Municipality" adopted a decision on the Serbian territories. The Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), in co-operation with the JNA, had also been active in arming the Serb population of the municipality and in training paramilitary units and militias. According to Dr. Andrew James Gow, an expert witness during ICTY trial, the SDS distributed around 400 weapons to Serbs in the area.[11]

Konjic was also included in those areas claimed by Croatia in Bosnia and Herzegovina as part of the "Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia", despite the fact that the Croats did not constitute a majority of the population there either. Thus, there were HVO units established and armed in the municipality by April 1992.

Following the international recognition of the independent Bosnian state and the walk-out of SDS representatives from the Municipal Assembly a War Assembly was formed to take charge of the defence of the municipality. Between 20 April and early May 1992 Bosnian government forces seized control over most of the strategic assets of the Municipality and some armaments. However, Serb forces controlled the main access points to the municipality, effectively cutting it off from outside supply. Bosniak refugees began to arrive from outlying areas of the municipality expelled by Serbs, while Serb inhabitants of the town left for Serb-controlled villages according to the decision made by Serb leadership.

On 4 May 1992, the first shells landed in Konjic, thought to be fired by the JNA and other Serb forces from the slopes of Borašnica and Kisera.[11] This shelling, which continued daily for over three years, until the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, inflicted substantial damage and resulted in the loss of many lives as well as rendering conditions for the surviving population even more unbearable. With the town swollen from the influx of refugees, there was a great shortage of accommodation as well as food and other basic necessities. Charitable organizations attempted to supply the local people with enough food but all systems of production foundered or were destroyed. It was not until August or September of that year that convoys from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) managed to reach the town, and all communications links were cut off with the rest of the State. A clear priority for the Konjic authorities was the de-blocking of the routes to Sarajevo and Mostar. This objective required that the Serbian forces holding Bradina and Donje Selo, as well as those at Borci and other strategic points, be disarmed. Initially, an attempt was made at negotiation with the SDS and other representatives of the Serb people in Bradina and Donje Selo. This did not, however, achieve success for the Konjic authorities and plans were made for the launching of military operations by the Joint Command.[11]

The first area to be targeted was the village of Donje Selo. On 20 May 1992 forces of the TO and HVO entered the village. Bosnian government soldiers moved through Viniste towards the villages of Cerići and Bjelovcina. Cerići, which was the first shelled, was attacked around 22 May and some of its inhabitants surrendered. The village of Bjelovcina was also attacked around that time. According to witnesses heard by the ICTY, the Serb-populated village of Bradina was shelled in the late afternoon and evening of 25 May and then soldiers in both camouflage and black uniforms appeared, firing their weapons and setting fire to buildings.[11] Many of the population sought to flee and some withdrew to the centre of the village. These people were, nonetheless, arrested at various times around 27 and 28 May, by TO, HVO and MUP soldiers and police.

The inmates

The military operations resulted in the arrest of many members of the Serb population. The former JNA Čelebići compound was chosen out of necessity as the appropriate facilities for the detention of prisoners in Konjic. Many of the men who were rounded up and disarmed were elderly or infirm.[8] The majority of the prisoners who were detained between April and December 1992 were men, captured during and after the military operations at Bradina and Donje Selo and their surrounding areas. According to the Bradina witnesses' testimonies, after the village was set ablaze, they were taken to the camp despite the fact that out of the 600 or so inhabitants of the village, only 20-25 had any weapons.[12]These Bradina detainees, who numbered about 70-80, were taken directly to Hangar 6 and appear to have been the first group to be placed in that building. At the end of May, several groups were transferred to the Čelebići prison-camp from various locations. For example, a group of around 15-20 men from Cerići were captured on 23 May 1992 and taken to Čelebići that day. Another group was taken near Bjelovcina around 22 May and spent one night at the sports hall at Musala before being transported to the Čelebići prison-camp.[7]

Military police also arrested many members of the male population of Brđani at the end of May and took them in a truck to the camp. A larger group was arrested in the centre of Bradina on 27 May and made to walk in a column along the road to Konjic. When these people reached a tunnel in the road, which had been blown up, they were searched and beaten by their captors before being loaded into trucks and taken to the camp. Others were arrested individually or in smaller groups at their homes or at military check points, in, amongst other places, Bradina, Vinište, Ljuta, Kralupi and Homolje, or upon surrender or capture during and after the operation in Donje Selo. Upon arrival at the camp, they were lined up against a wall near the entrance and searched and made to hand over valuables. In addition, several witnesses stated that they were severely beaten at that time by soldiers and guards.[7]

A Military Investigating Commission was constituted after the arrest of persons during the military operations, whose purpose was to establish the responsibility of these persons for any crimes. The Commission comprised representatives of both the police and the Croat Defence Council (HVO), as well as the Bosnian Territorial Defence (TO), who were each appointed by their own commanders. However, it was made evident during the trial that the Commission had been created as a façade to give the Čelebići camp some semblance of legality. It only worked for one month: its members were so horrified by the conditions the detainees were living in, the injuries they suffered, and the state of terror prevailing in the camp, that they resigned en masse.[2] Nevertheless, the Commission interviewed many of the Celebici inmates and took their statements, as well as analyzing other documents which had been collected to determine their role in the combat against the Konjic authorities and their possession of weapons. As a result, prisoners were placed in various categories and the Commission compiled a report recommending that certain persons be released. Some of the individuals who had been placed in the lower categories were subsequently transferred to the sports hall at Musala. From May until December 1992, individuals and groups were released from the Čelebići prison-camp at various times, some to continued detention at Musala, some for exchange, others under the auspices of the International Red Cross, which visited the camp on two occasions in the first half of August.[7]

Conditions and treatment in the camp

According to human rights investigators, the prisoners were scarcely fed bread and given water to drink. They rarely bathed, slept on concrete floors without blankets, and many were forced to defecate on the floor.[8] Serbian survivors said soldiers entered the base at night and beat prisoners with clubs, rifle butts, wooden planks, shovels and pieces of cable. Some of the prisoners testified to having their body parts doused in gasoline before being set alight.[12] Pliers, acid, electric shocks and hot pincers were also used to torture prisoners.[13] Investigators say that between May and August, about 30 prisoners died from the beatings and a few others were killed by the soldiers. Several of these victims were elderly. The few women in the camp were kept separate from the men and frequently raped.[14]

ICTY trial and convictions

- Zdravko Mucić (an ethnic Croat), commander of the prison camp: found guilty of willfully causing great suffering or serious injury, unlawful confinement of civilians, willful killings, torture, inhuman treatment and given 9 years. Granted early release on July 18, 2003.[7]

- Hazim Delić (Bosniak), deputy commander: found guilty of willful killings, torture, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury, inhuman treatment and given 18 years. Granted early release on June 24, 2008.[7]

- Esad Landžo (Bosniak), guard: found guilty of willful killing, torture, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury and given 15 years. Granted early release on April 13, 2006.[7]

In the case of Zejnil Delalić, it was found that he did not have enough command and control over the prison camp and the guards who worked there to entail criminal responsibility for their actions.[7]

See also

- Gabela camp

- Hazim Delić

- Heliodrom camp

- Keraterm camp

- Manjača camp

- Omarska camp

- Trnopolje camp

- Uzamnica camp

- Vilina Vlas

- Vojno camp

References

- ^ "Celebici Case: The Judgement Of The Trial Chamber". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- ^ a b c d "Crimes Against Serbs in the Čelebići Camp" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- ^ Rowland, Robin. "The privatization of war crimes". CBC News.

- ^ Dzidic, Denis. "Bosniaks Mark Closure of Detention Camp for Serbs". Balkan Insight.

- ^ "Hague president pays respects to victims". B92.

- ^ a b Nettelfield, Lara J. (2010). Courting Democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22, 197. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Case Information Sheet: "Čelebići Camp" (IT-96-21) Mucić et al" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- ^ a b c Hedges, Chris. "Balkan War Crimes: Bosnia Is First to Turn In Its Own". The New York Times.

- ^ "Three guilty in Bosnia trial". BBC News.

- ^ "Landmark cases". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- ^ a b c d e "Judgment of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in the case of Delalic et al. (I.T-96-21) "Celebici" 16 November 1998 Part II". Pratique de l'histoire et dévoiements négationnistes.

- ^ a b "Celebici Trial. Tribunal Update 21: Last week in The Hague (March 24-29, 1997)". Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

- ^ Simons, Marlise. "A War-Crimes Trial, but of Muslims, Not Serbs". The New York Times.

- ^ Stover, Eric (2011). The Witnesses: War Crimes and the Promise of Justice in The Hague. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 69.