2000s commodities boom

The 2000s commodities boom or the commodities super cycle[1] was the rise, and fall, of many physical commodity prices (such as those of food, oil, metals, chemicals, fuels and the like) during the early 21st century (2000–2014),[2] following the Great Commodities Depression of the 1980s and 1990s. The boom was largely due to the rising demand from emerging markets such as the BRIC countries, particularly China during the period from 1992 to 2013,[2] as well as the result of concerns over long-term supply availability.[citation needed] There was a sharp down-turn in prices during 2008 and early 2009 as a result of the credit crunch and sovereign debt crisis, but prices began to rise as demand recovered from late 2009 to mid-2010.[citation needed]

Oil began to slip downwards after mid-2010, but peaked at $101.80 on 30 and 31 January 2011, as the Egyptian revolution of 2011 broke out, leading to concerns over both the safe use of the Suez Canal and overall security in Arabia itself. On 3 March, Libya's National Oil Corp said that output had halved due to the departure of foreign workers. As this happened, Brent Crude surged to a new high of above $116.00 a barrel as supply disruptions and potential for more unrest in the Middle East and North Africa continued to worry investors.[3] Thus the price of oil kept rising into the 2010s. The commodities supercycle peaked in 2011,[notes 1] "driven by a combination of strong demand from emerging nations and low supply growth."[1][notes 2] Prior to 2002, only 5 to 10 per cent of trading in the commodities market was attributable to investors.[1] Since 2002 "30 per cent of trading is attributable to investors in the commodities market" which "has caused higher price volatility."[1][notes 3]

The 2000s commodities boom is comparable to the commodity supercycles which accompanied post–World War II economic expansion and the Second Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century.[2]

Background of depressed prices

The prices of raw materials were depressed and declining from, roughly, 1982 until 1998. From the mid-1980s to September 2003, the inflation-adjusted price[citation needed] of a barrel of crude oil on NYMEX was generally under $25/barrel. Since 1968 the price of gold has ranged widely, from a high of $850/oz ($27,300/kg) on 21 January 1980, to a low of $252.90/oz ($8,131/kg) on 21 June 1999 (London Gold Fixing).[4]

The analysis of this period is based on the work of Robert Solow and is rooted in macroeconomic theories of trade including the Mundell–Fleming model.[5] One opinion stated that

"The volatility and interest rates found its way into commodity inputs and all sectors of the world economy."[6]

Hence, in the case of an economic crisis commodities prices follow the trends in exchange rate (coupled) and its prices decrease in case there are downward trends of diminishing money supply.[5]

Foreign exchange impacts commodities prices and so does money supply: the advent of a crisis will pull commodities prices down.[5]

Boom

A commodity price bubble, known as the 2000s commodities boom, was created following the collapse of the mid-2000s housing bubble. Commodities were seen as a safe bet after the bubble economy surrounding housing prices had gone from boom to bust in several western nations, including the UK, USA, Ireland, Greece and Spain.[citation needed] Advisers claimed that commodity prices could be predicted better than stocks, since they are traded for actual usage and the price is based on supply and demand, while stocks are bought for speculation and news immediately influence prices. Still commodity prices have fluctuated outside predictions.

The renewed interest in coal by China's and Taiwan's energy companies and the rise of alternative power sources like wind farms helped modify coal prices over the 2000s. [citation needed]

Chlorine price steadily increased throughout 2007 and early 2008 as demand for PVC and some metals like copper, neodymium and tantalum rose due to the increased growth of the BRIC countries' demand for electrical goods. Russia increased production, but the US offset this with production cuts in the late 1990s and mid-2000s.[citation needed]

Phosphorus, rhodium, molybdenum, manganese, vanadium and palladium are used in high grade steels, oil based lubricants, automotive catalytic converters, chemical plants' catalysts, electronics, TV screens and in radio isotopes.[7] Demand for these metals appeared to be increasing as computers and mobile phones became more popular in the mid to late 2000s. Thulium is used in x-ray tubes and neodymium is used in high strength/high grade magnets.[citation needed]

Molybdenum, rhodium, neodymium and palladium are relatively scarce metals, while manganese and vanadium are, like phosphorus and sulfur, fairly abundant for minor minerals. The major metals such as iron, lead and tin are commonplace.[citation needed]

Recycling of the aluminum, ferrous metals, copper fractions, gold, palladium and platinum in mobile phones and computers had got under way by the mid-2000s.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Battery recycling has helped bring down both the nickel and cadmium prices.

Sulfuric acid (an important chemical commodity used in processes such as steel processing, copper production and bioethanol production) increased in price 3.5-fold in less than 1 year while producers of sodium hydroxide have declared force majeure due to flooding, precipitating similarly steep price increases.[14][15]

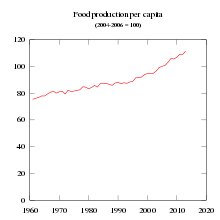

Food

Corn, wheat, rice, cocoa and Soya beans

Both a rising global population and a sharp decline in food crop production in favour of a sharp rise in biofuel crops helped cause a sharp rise in basic food stock prices.[16] Ethiopia also saw a drought threaten its already frail farm lands in 2007.[17] Cocoa was also affected by a bad crop in 2008, due to disease and unusually heavy rain in parts of West Africa.[citation needed]

Rising demand in both India and Egypt helped to ramp up demand for American wheat during the bull market during August 2007.[18] Discounted wheat sold at about £11–£15/t. August 2007, with non discounted wheat at slightly higher price. The November 2007 wheat futures market was trading at nearly £165/t, with November 2008 contracts at £128.50.[18] The market became rather bearish as non-futures prices froze and stagnated in December 2007.[19] The price of wheat reached record highs after Kazakhstan began to limit supplies being sold overseas in early 2008, but had slowed down by late 2008. Food riots hit Egypt on 12 April 2008, as national bread prices rose rapidly in March and April 2008.[20]

In late April 2008 rice prices hit 24 cents (U.S.) per U.S. pound, more than doubling the price in just seven months. The price of wheat had risen from an already high £88 per tonne to £91 from January to March 2010, due to the bullish market and currency concerns.[21] This led to food riots in places such as Haiti, Indonesia, Côte d'Ivoire, Uzbekistan, Egypt[22][23] and Ethiopia.[17]

On 31 July, leading economists predicted that food prices, especially wheat would rise in Chad as Russia ended exports due to a domestic drought destroying their wheat and barley harvests.[24] By 3 August, wheat prices stood at $7.11 per bushel[25] due to the Russian export ban.

Paper

Recycled paper

The price of recycled paper has varied greatly over the last 30 or so years.[26][27] [28][29] [30][31][32] The German price of €100/£49 per tonne was typical for the year 2003[29] and it steadily rose over the years. By September 2008 saw American price of $235 per ton had fallen to just $120 per ton,[26] and in January 2009, the UK's fell from about £70.00 per ton to only £10.00 per ton in six weeks.[27][30] The slump was probably due to the economic down turn in East Asia causing the market for waste paper drying up in China.[30] 2010 prices averaged $120.32 at the start of the year, but saw a rapid rise in global prices in May 2010,[28] reaching $217.11 per ton in the USA in June 2010 as China's paper market began to reopen.[28]

Fuel

Coal

Coal prices rose to A$73 per tonne in September[33] and then up to A$84 per tonne in the October 2009[33] due to renewed interest by China's and Taiwan's energy companies.

Oil

During 2003, the price rose above $30, reached $60 by 11 August 2005, and peaked at $147.30 in July 2008.[34] Commentators attributed the heavy price increases to many factors, including reports from the United States Department of Energy and others showing a decline in petroleum reserves,[35] worries over peak oil,[36] Middle East tension, and oil price speculation.[37]

For a time, geo-political events and natural disasters indirectly related to the global oil market had strong short-term effects on oil prices, such as North Korean missile tests,[38] the 2006 conflict between Israel and Lebanon,[39] worries over Iranian nuclear plans in 2006,[40] Hurricane Katrina,[41][42] and various other factors.[43] By 2008, such pressures appeared to have an insignificant impact on oil prices given the onset of the global recession.[44] The recession caused demand for energy to shrink in late 2008, with oil prices falling from the July 2008 high of $147 to a December 2008 low of $32.[45] Oil prices stabilized by October 2009 and established a trading range between $60 and $80.[45]

The price of oil nearly tripled from $50 to $147 from early 2007 to 2008, before plunging as the financial crisis began to take hold in late 2008.[46] Experts debate the causes, which include the flow of money from housing and other investments into commodities to speculation and monetary policy [47] or the increasing feeling of raw materials scarcity in a fast-growing world economy and thus positions taken on those markets, such as Chinese increasing presence in Africa. An increase in oil prices tends to divert a larger share of consumer spending into gasoline, which creates downward pressure on economic growth in oil importing countries, as wealth flows to oil-producing states.[48]

In January 2008, oil prices surpassed $100 a barrel for the first time, the first of many price milestones to be passed in the course of the year.[49] In July 2008, oil peaked at $147.30[50] a barrel and a gallon of gasoline was more than $4 across most of the US. The high of 2008 may have been part of broader pattern of spiking instability in the price of oil over the preceding decade.[51] This pattern of instability in oil price may be a product of peak oil. There is concern that if the economy was to improve, oil prices might return to pre-recession levels.[52]

In testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation on 3 June 2008, former director of the CFTC Division of Trading & Markets (responsible for enforcement) Michael Greenberger specifically named the Atlanta-based IntercontinentalExchange, founded by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and British Petroleum as playing a key role in the speculative run-up of oil futures prices traded off the regulated futures exchanges in London and New York.[53]

The price of oil rose to $77 per barrel on 24 June as a cyclone begins to form in the south western Caribbean.[54] The price for July 2010 was about $84–$90 per barrel of crude oil.

Oil prices ended the year at $101.80, falling to $100.01 per barrel on 30 and 31 January 2011.[citation needed], then the Egyptian civil war broke out, as it theoretically put the use of Suez Canal at risk.[55] Making matters worse, a gas pipeline to Jordan was blown up by saboteurs in the Sinai Peninsula. Prices remained steady until a dramatic drop began the 2010s oil glut.

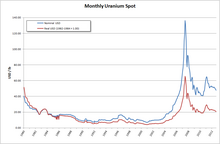

Uranium

Uranium traded at about $15–$20/kg since the late 1980s due to a 10-year secular bear market, with a 2001 low of just over $10/kg. The Uranium bubble of 2007 started in 2005[57] and began to accelerate badly with the 2006 flooding of the Cigar Lake Mine in Saskatchewan.[58][59][60] Uranium prices peaked at roughly $300/kg in mid-2007,[61] began to fall in mid-2008 and are now (end 2010) hovering about $100/kg.[62] The stock prices of many uranium mining and exploration companies rose sharply, only to fall later in this boom.[58]

There was also a brief resurgence of interest in nuclear power by the UK government between 2006 and 2008 due to the apparently insecure nature of Middle Eastern oil and after the closure of several old and economically/environmentally unviable coal fired power stations at the time. This helped the uranium price to rally at this date.

Precious metals

Gold

There was a sharp shift in the prices of gold and, to a lesser extent, both silver and platinum. Prices were at or near an all-time high in late 2010 due to people using the precious metals as a safe haven for their money as both the de facto value of cash and the stock market prices became more erratic in the late 2000s.

The period from 1999 to 2001 marked the "Brown Bottom" after a 20-year secular bear market at $252.90 per troy ounce.[63] Prices increased rapidly from 1991, but the 1980 high was not exceeded until 3 January 2008 when a new maximum of $865.35 per troy ounce was set (a.m. London Gold Fixing).[64] Another record price was set on 17 March 2008 at $1,023.50/oz ($32,900/kg) (am. London Gold Fixing).[64] In the fall of 2009, gold markets experience renewed momentum upwards due to increased demand and a weakening US dollar. On 2 December 2009, gold passed the important barrier of US$1,200 per ounce to close at $1,215.[65] Gold further rallied hitting new highs in May 2010 after the European Union debt crisis prompted further purchase of gold as a safe asset.[66][67][68]

Since April 2001, the gold price has more than tripled in value against the US dollar,[69] prompting speculation that the long secular bear market had ended and a bull market has returned.[70] Gold's price finally stood at $1,350 per troy oz on 1 July 2010.[71]

On 7 October 2010, it cost $1,364.60 per troy ounce,[72] by 7 December reached the all time nominal historic high of $1,429.05 per troy ounce.

Note that the analysis of log-linear oscillations in the gold price dynamics for 2003–2010 conducted in 2010 by Askar Akayev's research group allowed them to forecast the collapse in gold prices in June – August 2011.[73] Note that the team had already forecasted correctly with a one-day accuracy the start of the collapse of the silver bubble.[74]

Silver

Silver cost $4 per troy ounce in 1992,[66] started to rise rapidly in early 2004,[66] reached $18 per troy oz by late 2007, slipped badly to $10 per troy oz during the Credit Crunch of 2008,[66] but was selling in late 2009 and again in early 2010 at just under $18 per troy oz of metal.[66] A year later, the Feb 2011 average was over $30 per oz of silver.[75] On 29 April 2011, silver price reached $47.94 but fell by 12% on 2 May 2011.[66] Prices range around $20–$25 in 2013-2014.

Platinum

Platinum first sold at about $350 per troy oz in 1992[66] and stayed rather flat save for a small dip to about $325 per troy oz in the mid-1990s[66] and an equally small rise to about $375 per troy ounce in the Millennium period. It started to gain value in mid-2002[66] and grew on an experiential curve model as the prices then began to move sharply upwards.[66] The high point was when it was trading for $2,200 per troy oz in early 2007.[66] Prices declined to $800 per troy oz in January 2008,[66] but the price had increased $1,600 per troy oz by early 2010.[66]

Rhodium

Rhodium prices rose brief during the millennium period[66] due to increased demand, then collapsed to nearly their original 1995-7 starting price of $500/oz between 2002 and 2004.[66]

Later on, the mysterious and unexpected Rhodium price bubble of 2008 suddenly increased prices from just over $500/oz in late 2006 to $9,000/oz-$9,500/oz in July 2008,[66] only for the price then to tumble down only $1,000/oz in January 2009.[66][76] Both an increase in demand in the American automotive industry, a herd instinct among investors, a then bullish market in rare metals and a rogue speculator or rogue speculators on Wall Street were all at least partly to blame for the sudden rise and fall in the rare metal's price.[77]

Rhodium is mainly mined as a by-product of other metals such as platinum, so the production is based on production of other metals and therefore on demand of them, and less on the demand of rhodium.

Palladium

Most palladium is used for catalytic converters in the automobile industry.[78] It is also used for some medical, high grade steel, industrial, dental and electronic purposes.

Palladium prices rose sharply during the millennium period[66] due to increased demand, then collapsed to nearly their original starting price by the end 2002,[66] only to start to rise less dramatically in the year 2006.[66] Palladium prices in 1992 and 2002–04 was about $200/oz. It rapidly shot up to approximately $1,000/oz between 1999–2001 and collapsed to only $200/oz by late 2002, but is now just under $500/oz per of Palladium in 2010.[66]

In the run up to 2000, Russian supply of palladium to the global market was repeatedly delayed and disrupted[79] because the export quota was not granted on time, for political reasons. The ensuing market panic drove the palladium price to an all-time high of $1,100 per troy ounce in January 2001.[80] Around this time, the Ford Motor Company, fearing auto vehicle production disruption due to a possible palladium shortage, stockpiled large amounts of the metal purchased near the price high. When prices fell in early 2001, Ford lost nearly US$1 billion.[81] World demand for palladium increased from 100 tons in 1990 to nearly 300 tons in 2000. The global production of palladium from mines was 222 metric tons in 2006 according to the USGS.

Rhenium

Because of the low availability relative to demand, rhenium is among the most expensive industrial metals, with an average price exceeding US$6,000 per kilogram, as of mid-2009. It first traded in 1928 at US$10,000 per kilogram of metal, but traded at US$250 per Troy ounce in mid-2010.[82] It traded in July 2010, at about US$4,000–4,500/kg.[83]

Other Industrial Metals

Aluminium

Aluminium is a widely used, mined, refined and trusted metal.[84][85] The fortunes of this metal are linked to the rise and fall of the aircraft, electrical and automotive industries.[86][87]

The price of aluminium was 80 US cents per lb in 1995 and 45 cents per lb in 1998 and hovered around this until the January 2003, when it started to rise to $1.50 per pound and in 2006 and $1.40 per lb in the December 2007.[88][89] It collapsed down to a mere 60 cents per lb in the November 2008, but is now hovering at about $1.00 per lb, with a new April peak of $1.10 per pound of aluminium.[88][89]

Nickel

The price of nickel boomed in the late 1990s, then imploded from around $51,000 /£36,700 per metric tonne in May 2007 to about $11,550/£8,300 per metric ton in January 2009. Prices were only just starting to recover as of January 2010, but most of Australia's nickel mines had gone bankrupt by then.[90] As the price for high grade nickel sulphate ore recovered in 2010, so did the Australian mining industry.[91] Battery recycling has helped bring down both the nickel and cadmium prices.

Copper

It was also noticed that a copper price bubble was occurring at the same time as the oil bubble. Copper traded at about $2,500 per metric tonne from 1990 until 1999, when it fell to about $1,600.[92] The price slump lasted until 2004 which saw a price surge that had copper reaching $9,000 per tonne in the May 2006, but it eventually fell down to $7,040 per tonne in early 2008.[93] When the slump came, it hit some copper mining countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) very hard. Mining authorities announced on 10 December 2009, that the Dikulushi mine, which is situated in the D.R.C.'s Katanga Province, would close due to poor copper prices.[94] It reopened in July 2010. The price rose again to over $10,000 in early 2011 but soon fell to below $8,000, around where it was fairly stable during 2012.[95] Unfortunately the high prices have caused a heavy increase in theft of copper cables, causing interruptions in electrical supply.[96][97] During 2013-2014 there has been a slow decline to below $7000.

Iron

The prices of iron ore rose sharply from around $10 per metric ton in 2003 to around $170 in April 2009 (transported to China). After that (written September 2013) the price was between $100 and $150;[98] in September 2014 it started dropping precipitously, and was below $70 per ton in December 2014. The price of steel (at steel plants in Japan) has risen from around $300 per metric ton in 2003 to $1000 in late 2008, stabilizing at $800 in 2012[99]

The rise in prices has made abandoned mines to reopen and new ones to open.

Lead

The price of lead rose sharply in early 2007, then collapsed to nearly their original starting price by the end of the next year.[100] Lead prices began to rise in early 2007 due to increased worldwide demand. Prices were about $1,200 per tonne of lead in the July, then rose to $2,220 per tonne by September and collapsed back down to $1,200 per tonne in the October of that year. Despite the bullish market condition, the price had collapsed by the July 2009 and was only worth about $1,400 per tonne of lead.[101] The lead and zinc markets became rather bearish for several months afterwards. Prices were hovering at between $1,770 and $2,175 per tonne[102] as the markets became more bullish and increased prices after China's car scrapping scheme had caused a general upturn in lead, zinc, cadmium and aluminium production.[102][103] By the June 2010, prices stood at only $870 per tonne, and were back to about $2,200 in the July 2010.[103][104][105][106]

Zinc

The price of zinc rose sharply in early 2007 after a five-year secular bear market, then collapsed to nearly their original starting price by the end of the next year.[100] Zinc also exhibited similar bullish trading patterns as most metals did since 2004, but with a different overall price.[103]

Zinc sale prices were 80 cents per pound in July 2008,[107] which was typical of its 2004–2008 pricing levels.[107] By January 2009 it had bottomed out and was worth 45 cents per lb.[107] A spectacular bull market and increased Chinese interest in galvanised construction steel caused prices to top off at $1.20 per pound of metal by January 2010.[107] It then quickly fell back to a routine 80 cents by July 2010.[107]

Zinc is popular in manufacturing and building; its ability to create corrosion-resistant zinc plating of steel (hot-dip galvanizing) is the major application for zinc. Other applications are in batteries and alloys, such as brass. A variety of zinc compounds are commonly used, such as zinc carbonate and zinc gluconate (as dietary supplements), zinc chloride (in deodorants), zinc pyrithione (anti-dandruff shampoos), zinc sulfide (in luminescent paints), and zinc methyl or zinc diethyl in the organic laboratory.

Neodymium

Neodymium, a fairly rare metal which is used in high grade magnets,[108][109][110] saw its prices rise due to increased demand, as were typical of this general market trend. The average price was $16.10 per kg in November and December 2009,[111] but it began trading in June 2010 at $20–$45 per kg.[112]

Neodymium serves as a constituent of high strength neodymium magnets, which are widely used in loudspeakers, computer hard drives, high power-per-weight electric motors (e.g. for those in hybrid cars) and in high efficiency generators (such as aircraft and wind turbine generators).[113]

There was also a strong resurgence of interest in wind farms by the UK government between 2008 and 2010 due to the continuing fears of insecurity in Middle Eastern oil supplies to the industrialised nations and after the closure of several old and economically/environmentally unviable coal-fuelled power stations earlier that decade. This helped the price to rally in 2010.[citation needed]

Other metals

The cadmium, tantalum, manganese, thulium, tin, chromium, indium, columbium/niobium, cobalt, molybdenum and vanadium prices rose sharply in early 2007,[66][100] then collapsed to nearly their original starting price by the end of the next year[66][100] [114] due to uncertainty about supplies matching the demand, especially those of the BRIC countries' electronics industries in iPods, computers, mobile phones, et al.

Niobium is used in the steel of gas pipe lines due to the alloy's high strength and low corrosion rate.[115]

Battery recycling has helped bring down both the nickel and cadmium prices. About 86% of all cadmium production was used in batteries during 2009. The rapid growth of wind farms and heavy duty magnets has made neodymium prices rally again and both Brazil and China's renewed interest in high grade steel has improved the Vanadium price recently. The way these metal's prices rose and fell due to increased demand, were typical of this general market trend.

Chemicals

Sulphuric acid

In 2002, 95% pure sulphuric acid cost £55 and 90% acid cost £40 per tonne.[116] Due to floods in Poland and increased demand in China, the acid's price soared to $329/tonne in May 2008, from just $90/tonne in October 2007. It has become steadily cheaper since the start of 2010.

Most industrial chemicals exhibited similar price trends due to bad weather in the EU and USA along with increased demand by the BRIC nations.

Non metals

Chlorine

Chlorine products such as P.V.C. plastics, caustic soda, industrial paper bleach and ordinary household and industrial bleachs saw their prices rise sharply in 2008 as a result of volatility on the world's chlorine market.

As a result of fight of supply and high operating rates in May 1997, two chlorine producers took the bold initiative of calling for an average price rise of $25 per short ton. Other producers were considering bringing the total price increase for the 1997 product year to date of up to $80 per short and fob ton, from $45–$50 per short and fob ton in May 1996. This occurred as both rapidly ascending demand from the vinyl polymer chain market and the unusually strong seasonal demand and no new production capacity on the immediate horizon coincided. The price increase had its firm foundations in the incumbent bullish market dynamics of the mid-2000s. Occidental Chemical Corporation suggested a minor rise as other firms took a "wait-and-see approach" and Russia raised production slightly to ease the cost of domestic bleach and swimming pool chloro-tablet costs.[citation needed]

Chlorine prices rose in May 2005 as both growing energy costs, shrinking supply and high market tariffs in the EU, NAFTA and Latin America,[117] the increased use of chlorine-based chemicals for the aquatics industry.[117] The price of chlorine caustic was $350 per dry short ton, up from $100 last March.[117] Chlorine was priced at $330 per dry short ton, up $130 on 2008's price of $200.[117]

The gas's price steadily increased throughout 2007 and early 2008 as demand for P.V.C. and some metals like copper, Neodymium and Tantalum rose due to the increased growth of the BRIC countries demand for electrical goods.

America's chlorine prices rose suddenly from about $125–$150 per ton fob between June and August 2009 months on a sharp rise in chlor-alkali production and capacity cuts after a year in which production quotes largely stay flat.[118] The spot price surged more than 300% to about $475–$525 ton fob in August 2009.[118] Both Russia and the European Union were also increasing chlorine production to stabilise world prices.[118]

Non discounted American chlorine was priced at $390–410 short ton and discounted prices stood at $300 per short ton between November 2009 and February 2010.[119] As the European chlorine production spiked in November to a daily output of 26,971 tonnes, before falling to 23,667 short ton in December due to the Christmas and New Year holidays.[119] Production was about European production was 25.8% higher than December 2008 levels.[119]

Late-2000s economic fallout

Many firms, individuals, and hedge funds went bankrupt or suffered heavy losses due to purchasing commodities at high prices only to see their values decline sharply in mid to late 2008. Many manufacturing companies were also crippled by the rising cost of oil and other commodities such as transition metals.

The food and fuel crises were both discussed at the 34th G8 summit in July 2008.[120]

The 2008 price glitch

In the second half of 2008, the prices of most commodities fell dramatically on expectations of diminished demand in the world recession and credit crunch.[121] Prices began to rise again in late 2009 to mid-2010 (as supply could not meet demand), triggering another round of boom that lasted until 2014, when fossil fuels and metals prices collapsed in a far more prolonged fashion that looks to far eclipse that of 2008.[citation needed]

Mine closures

The heavy price volatility caused a sudden boom then bust in the mining industry across the world, e.g. in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Canada, China, Sweden and Australia. The $900,000,000 Tenke Fungurume copper-cobalt mining project in the Democratic Republic of Congo was cleared on February 2008 for building to start in a years time and then Luanshya Copper Mine in Zambia closed on 6 March 2009. Zimbabwe and Australia also saw nickel and copper mines open close during this time. China has opened several new coal mines in Qinghai province during the years 2007 and 2008.[122][123][124][125][126][127][128]

Opinions on the commodities bubble

Coincidentally, long-only commodity index funds started just before the bubbles, became popular at the same time – by one estimate investment increased from $90 billion in 2006 to $200 billion at the end of 2007, while commodity prices increased 71% – which raised concern as to whether these index funds caused the commodity bubble.[129] The empirical research has been mixed.[129]

In February 2008, analyst Gary Dorsch wrote:

Commodities have historically been regarded as wildly volatile and risky, but since 2006, crude oil, gold, copper, silver, platinum, cocoa, and grains have soared, hitting record highs, and have trounced returns in the mismanaged G-7 stock markets ... A remarkable run-up in prices of wheat, corn, oilseeds, rice, and dairy products, along with sharply higher energy prices, have been blamed on supply shortfalls, strong demand for bio-fuels, and an inflow of $150 billion from investment funds. From a year ago, Chicago wheat futures have soared +120%, corn +20%, and soybeans are +80% higher. Rough rice is up 55%, and platinum touched $2,000 /oz, up 80% from a year ago, while US cocoa futures hit a 24-year high ... Fund managers are pouring money into commodities across the board as a hedge against the explosive growth of the world's money supply, and competitive currency devaluations engineered by central banks.[130]

Economist James D. Hamilton has argued that the increase in oil prices in the period of 2007 to 2008 was a significant cause of the recession. He evaluated several different approaches to estimating the impact of oil price shocks on the economy, including some methods that had previously shown a decline in the relationship between oil price shocks and the overall economy. All of these methods "support a common conclusion; had there been no increase in oil prices between 2007:Q3 and 2008:Q2, the US economy would not have been in a recession over the period 2007:Q4 through 2008:Q3."[131] Hamilton's own model, a time-series econometric forecast based on data up to 2003, showed that the decline in GDP could have been successfully predicted to almost its full extent given knowledge of the price of oil. The results imply that oil prices were entirely responsible for the recession; however, Hamilton himself acknowledged that this was probably not the case but maintained that it showed that oil price increases made a significant contribution to the downturn in economic growth.[132]

Aftermath

In the mid-2010s, China experienced a stock market crash and economic slowdown as it moved from manufacturing to a services industry.[133] Leftist pink tide governments in Latin America who created unsustainable policies based on China's commodity trade in the 2000s began to experience economic difficulties and began to experience a political decline as income dimished due to the end of the commodities boom.[134][135][136] As oil prices declined, Russia also had its economy falter as a result of mismanagement.[137]

Synoptic chart on 1990–2010 prices

This article needs to be updated. (May 2013) |

All prices are in either £, €, $/US$ or A$, depending on the nationality of sources available.

| Commodity | Image | 1990–2010 lowest price per unit | 1990–2010 highest price per unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | £11-£15 for discounted and slightly higher for non-discounted wheat (2007) | £91 for both(2010) | |

| Recycled paper | £10 (2009) | $235 (2008) | |

| Crude oil |  |

$30 (2005) | $147.30 (2008) |

| Copper |  |

$1,600 (1999) | $9,000 (2006) |

| Gold | $252.90 (1999) | Over $1900 (2011)[138] | |

| Aluminum |  |

$0.45 (1998) | $1.50 (2006) |

| Platinum | $325 (1994) | $2,200 (2007) | |

| Silver | $4 (1992) | $49.80 (April 2011) [139] | |

| Coal |  |

A$72.00 (2009) | A$112.50 (2010) |

| Nickel |  |

£8,300 (2009) | £36,700 (2007) |

| Uranium | $10 (2001) | $300 (2007) | |

| Rhodium | $500 (1995–1997, 2002–2004) | $9,500 (2008) | |

| Palladium | $200 (1992, 2002–2004) | $1,100 (2001) | |

| Zinc |  |

$0.45 (2009) | $1.20 (2010) |

| Neodymium |  |

$16.10 (2000s) | $45 (2010) |

| Lead | $870 (2010) | $2,220 (2007) | |

| Rhenium |  |

$4,000–$4,500 (2010) | $6,000 (2009) |

| Chlorine | $45–$50 for both classes (1996) | $475–$525 (2009) | |

| Sulfuric acid | £55 for 95% pure and £40 for 90% pure (2002) | $329 for both in (2008) |

See also

Notes

- ^ "Mark Pervan, global head of commodity strategy at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, said commodity prices peaked in the current cycle in early 2011." "International prices of five energy and metal commodities peaked between February and May of 2011. Since their respective peaks, the Brent crude oil benchmark has fallen 15 per cent, coal 42 per cent, copper 33 per cent, aluminium 37 per cent and iron ore 36 per cent."

- ^ Eugen Weinberg, head of commodity research at Commerzbank in Germany claimed the commodities super-cycle which began c. 2002, is not coming to an end but just 'taking a break.'

- ^ This article covers physical product (food, metals, energy) markets but not the ways that services, including those of governments, nor investment, nor debt, can be seen as a commodity. Articles on reinsurance markets, stock markets, bond markets, and currency markets cover those concerns separately and in more depth.

References

- ^ a b c d Ng 2013.

- ^ a b c Nelson D. Schwartz and Julie Creswell (23 October 2015). "A Global Chill in Commodity Demand Hits America's Heartland In China and other emerging markets, growth is waning and demand for the raw materials that drive the global economy has dried up". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Libya: US warships enter Suez Canal on way to Libyan waters. Telegraph (2 March 2011). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Kitco.com, Gold – London PM Fix 1975 – present (GIF). Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- ^ a b c Chimni, B.S. (1987). International Commodity Agreements A Legal Study. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7099-5420-0.

- ^ Commodity Trading Manual, By Patrick J. Catania, Chicago Board of Trade, Peter Alonzi, Chicago Board of Trade Market & Product

- ^ ClimaxMoly: How Is Molybdenum Used? Archived 12 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Climaxmolybdenum.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Mobile Phone Recycling, Information on. Envocare.co.uk (13 March 2011). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Urban miners look for precious metals in cell phones". Reuters. 27 April 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Guns, Money and Cell Phones – Global Issues. Globalissues.org. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Earth. Eoearth.org. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Mobile phones yield valuable raw materials – Case studies – Environment – Corporate responsibility Archived 7 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Nokia. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived 2 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sulfuric acid prices explode". Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dow Declares Force Majeure for Caustic Soda". Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Biofuels major cause of global food riots", Kazinform (Kazakhstan National Information Agency), 11 April 2008 Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Boris Heger (3 June 2008). "4.5 million drought-stricken Ethiopians need food aid". France24.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ a b Bull run on wheat prices shows no sign of slowing – 30 August 2007 – Farmers Weekly. Fwi.co.uk (30 August 2007). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Wheat prices to slow down in 2008? – 23 December 2007 – Farmers Weekly. Fwi.co.uk (23 December 2007). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Black, Ian (12 April 2008). "Struggling country where bread means life". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Market report: Wheat prices edge upwards – 24 March 2010 – Farmers Weekly. Fwi.co.uk (24 March 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Egyptian boy dies from wounds sustained in Mahalla food riots", International Herald Tribune. 8 April 2008

- ^ Steavenson, Wendell (9 January 2009). "It's the baladi, stupid". The Australian Financial Review. p. Perspectives Review supplement (pp. 3–5).

The difference between the subsidised and market price of bread [in Egypt] is exploited at every stage of production and sale, by importers, millers, warehousers, traders, bakers and consumers alike.

- ^ http://www.fews.net/.../MONTHLY%20PRICE%20WATCH%20July%202010.PDF [dead link]

- ^ A bushel and a peck: wheat prices rise by half – Leadership, business and management news, tips and features from MT and Management Today magazine. Managementtoday.co.uk (3 August 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b at Archived 12 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Treemaxx.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Sutherland, Keri; Gallagher, Ian (5 January 2009). "Recycling crisis: Taxpayers foot the bill for UK's growing waste paper mountain as market collapses". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ a b c Recycling and Composting Online. Recycle.cc (10 March 2011). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Tomlinson, Heather (6 April 2003). "Recycled paper up in price". The Independent. London. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ a b c Paper Recycling Crisis ?. Wild About Britain. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Loose Waste Paper Exchange Listings. Recycle.net. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ A Paper Recycling Business – Startup Guide. Howtoadvice.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Coal prices to surge in 2010 despite ample supply | 20 October 2009. www.commodityonline.com (20 October 2009). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Light Crude Oil EmiNY (QM, NYMEX): Weekly Price Chart". Tfc-charts.com. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^

"Record oil price sets the scene for $200 next year". AME. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Peak Oil News Clearinghouse". EnergyBulletin.net. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Hike in Oil Prices: Speculation – But Not Manipulation". Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Missile tension sends oil surging". CNN. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^

"Oil hits $100 barrel". BBC News. 2 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Iran nuclear fears fuel oil price". BBC News. 6 February 2006. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Macroeconomic Effects of Hurricane Katrina, CRS Report for Congress" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mortished, Carl (30 August 2005). "Hurricane Katrina whips oil price to a record high". The Times Online. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- ^ Gross, Daniel (5 January 2008). "Gas Bubble: Oil is at $100 per barrel. Get used to it". Slate. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Oil Prices Fall As Gustav Hits". Sky News. 2 September 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Tuttle, Robert; Galal, Ola (10 May 2010). "Oil Ministers See Demand Rising, Price May Exceed $85". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Light Crude Oil Chart". Futures.tradingcharts.com. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Conway, Edmund (26 May 2008). "Soros – Rocketing Oil Price is a Bubble". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mises Institute-The Oil Price Bubble". Mises.org. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Crude oil prices set record high 102.08 dollars per barrel". Retrieved 9 July 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Light Crude Oil EmiNY (QM, NYMEX): Monthly Price Chart". Tfc-charts.com. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ "Gail the Actuary – Was Volatility in the Price of Oil a Cause of the 2008 Financial Crisis?". Energybulletin.net. 8 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Oil prices and future economic stability https://www.thestar.com/business/article/535378

- ^ "Energy Market Manipulation and Federal Enforcement Regimes". Digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Oil rises towards $77 as Caribbean storm brews". Reuters. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ BBC News – Egypt unrest pushes Brent crude oil to $100 a barrel. Bbc.co.uk (31 January 2011). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "NUEXCO Exchange Value (Monthly Uranium Spot)". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Uranium Bubble & Spec Market Outlook. News.goldseek.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Uranium Has Bottomed: Two Uranium Bulls to Jump on Now. UraniumSeek.com (22 August 2008). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ TradeTech – In the Market Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Uranium.info. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Nuclear Engineering International Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Neimagazine.com (22 August 2008). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Random Roger: Uranium A Bubble?. Randomroger.blogspot.com (20 February 2007). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Dynamic Charting Tool | InvestmentMine. Infomine.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Watt, Holly; Winnett, Robert (15 April 2007). "Goldfinger Brown's £2 billion blunder in the bullion market". The Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "LBMA statistics". Lbma.org.uk. 31 December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gold hits yet another record high". BBC News. 2 December 2009. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Kitco price charts". Kitco.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "PRECIOUS METALS: Comex Gold Hits All-Time High". Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gold hits closing record; zips past $1,233/ounce Metals Stocks. MarketWatch. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Kitco.com 10 Year gold chart". Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gold starts 2006 well, but this is not a 25-year high! | Financial Planning". Ameinfo.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gold Bubble on the Verge of Bursting? – Precious Metals. Resource Investor. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Gold hits record, set for best week in six months". Reuters. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Askar Akayev, Alexey Fomin, Sergey Tsirel, and Andrey Korotayev. Log-Periodic Oscillation Analysis Forecasts the Burst of the "Gold Bubble" in April – June 2011 // Structure and Dynamics 4/3 (2010): 1–11. For a more technically sophisticated (but less easily understandable for a general audience) treatment of this subject see Log-Periodic Oscillation Analysis and Possible Burst of the "Gold Bubble" in June – August 2011 by Sergey Tsirel, Askar Akayev, Alexey Fomin, and Andrey Korotayev; see also Askar Akaev, Viktor Sadovnichiy, and Andrey Korotayev. Huge rise in gold and oil prices as a precursor of a global financial and economic crisis. Doklady Mathematics. 2011. Volume 83, Number 2, 243–246; On the Possibilities to Forecast the Current Crisis and its Second Wave. "Ekonomicheskaya politika". December 2010. Issue 6. Pages 39-46.; On the dynamics of the world demographic transition and financial-economic crises forecasts // The European Physical Journal 205, 355-373 (2012).

- ^ "Клиодинамика – 1 мая может лопнуть "серебряный" ценовой пузырь?". Cliodynamics.ru. 22 April 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Historical Silver Data and Charts – London Fix. Kitco.com (20 May 1999). Retrieved 2011-03-28. Archived 27 January 2010 at WebCite

- ^ "Historical Rhodium Charts". Kitco. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Can One Man's Actions Take $6 Billion In Value Out Of A Minor Metal Market In A Month? – Undesignated. Resource Investor. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Kielhorn, J.; Melber, C.; Keller, D.; Mangelsdorf, I. (2002). "Palladium – A review of exposure and effects to human health". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 205 (6): 417–32. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00180. PMID 12455264.

- ^ Williamson, Alan. "Russian PGM Stocks" (PDF). The LBMA Precious Metals Conference 2003. The London Bullion Market Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historical Palladium Charts and Data". Kitco. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ "Ford fears first loss in a decade". BBC News. 16 January 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ [2] Archived 27 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rhenium Prices Archived 16 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Metals Place (8 July 2007). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Aluminium | Essential information. Webelements.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ International Aluminium Institute. World-aluminium.org. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Aluminium International Today. Aluminiumtoday.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Old, Shelley. (2 July 2010) China's aluminium demand will rise: Rio Tinto – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Abc.net.au. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Dynamic Charting Tool | InvestmentMine. Infomine.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b Dynamic Charting Tool | InvestmentMine. Infomine.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Business | Miner BHP to lay off 6,000 staff". BBC News. 21 January 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "(AU) – Mincor's result reflects a return to better days for sulphide nickel". Proactive Investors. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Copper prices London". Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Historical Copper Prices, Copper Prices History". Dow-futures.net. 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ afrol News – Another DRC copper mine closed. Afrol.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "5 Year Copper Prices and Copper Price Charts - InvestmentMine". InfoMine. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Copper Theft Threatens U.S. Critical Infrastructure". Federal Bureau of Investigation. 15 September 2005. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "4 House Fires and Hundreds of Homes Without Power after Substation Targeted". metaltheftscotland.org.uk. 29 November 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Iron Ore - Monthly Price - Commodity Prices - Price Charts, Data, and News - IndexMundi". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Hot-rolled steel - Monthly Price - Commodity Prices - Price Charts, Data, and News - IndexMundi". Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d Current Primary and Scrap Metal Prices – LME (London Metal Exchange). Metalprices.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Standard Chartered ups 2010 lead price forecast". Reuters. 13 July 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ a b Lead prices plunge as LME stocks rise relentlessly | 19 February 2010. www.commodityonline.com (19 February 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Ecclestone bullish on zinc and lead prices by end of 2010 – Proactiveinvestors (UK) Archived 15 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Proactiveinvestors (18 June 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ European concerns lead to oil price drop | LiveWire Economics Blog. Livecharts.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Lead prices from the London Metal Exchange (LME), news, charts, historical prices. Metalprices.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Lead Prices News Archived 26 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Metalmarkets.org.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Zinc prices London". Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Periodic Table. Baotou.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Neodymium | Compare Hand Tools prices – price comparison at. Bizrate.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Nanotechnology at Work. PIDC. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Rare earth pricing resurges | Industrial Minerals. Mineralnet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Rare earth prices climbing | Industrial Minerals. Mineralnet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Gorman, Steve (31 August 2009). "Steve Gorman, ''As hybrid cars gobble rare metals, shortage looms,'' Reuters, Mon Aug 31, 2009". Reuters. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ ICA raises indium price to 640 per kg. Metal Bulletin (14 April 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Niobium or Columbium Facts – Periodic Table of the Elements. Chemistry.about.com (11 June 2010). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Costs of Chemicals Archived 26 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Ed.icheme.org (26 February 2002). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Chlorine getting more costly; prices could rise even more. | Marketing & Advertising – Price Management from. AllBusiness.com (1 May 2005). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Chlorine Prices Surge Amid Chlor-alkali Production Cuts :: Chemical Week. Chemweek.com (7 August 2009). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Chlorine Prices and Pricing Information. Icis.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Africa's Plight Dominates First Day of G8 Summit". Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Commodities crash". Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Collapse in metal values: Related mine closures – Minerals & Energy – Raw Materials Report. Informaworld.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Nickel Mine Closures 2008 Due to Demand Destruction and Low LME Price". Estainlesssteel.com. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Nickel in Australia. Chemlink.com.au (31 December 2003). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ at Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Jotafrica.com. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ DRC $900-million copper mine to come on stream in 2009. Miningweekly.com (6 January 2009). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ AM – WA town fear impact of nickel mine closure. Abc.net.au (22 January 2009). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Schifferes, Steve (6 March 2009). "Zambian miners hit by copper slump". BBC News. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ a b Irwin SH, Sanders DR. (2010). The Impact of Index and Swap Funds on Commodity Futures Markets. OECD Working Paper. doi:10.1787/5kmd40wl1t5f-en

- ^ Gary Dorsch (14 February 2008). "Central Bankers Fueling Global Commodity Inflation". SafeHaven.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamilton, James D. "Oil prices and the economic recession of 2007–08." Voxeu.org. 16 June 2009.

- ^ Did rising oil prices trigger the current recession? | vox – Research-based policy analysis and commentary from leading economists. Voxeu.org (13 January 2009). Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Vanderklippe, Nathan (17 August 2015), China's new economic reality, The Globe and Mail, retrieved 7 January 2016

- ^ Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (January–April 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). 38 (1). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro: 11–53.

The fate of Latin America's left turn has been closely associated with the commodities boom (or supercycle) of the 2000s, largely due to rising demand from emerging markets, notably China.

- ^ Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

As China industrialized in the first decade of the century, its demand for raw materials rose, pushing up the prices of South American minerals, fuels, and oilseeds. From 2000 to 2013, Chinese trade with Latin America rocketed from $12 billion to over $275 billion. ... Its loans have helped sustain leftist governments pursuing otherwise unsustainable policies in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, whose leaders welcomed Chinese aid as an alternative to the strict conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund or the financial markets. ... The Chinese-fueled commodity boom, which ended only recently, lifted Latin America to new heights. The region -and especially South America- enjoyed faster economic growth, a steep fall in poverty, a decline in extreme income inequality, and a swelling of the middle class.

- ^ "The Left on the Run in Latin America". The New York Times. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ "Oil and trouble". The Economist. 4 October 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Yousuf, Hibah. "Gold tops $1,900, looking 'a bit bubbly'".

- ^ "Silver $50: Three Years After the "Shortage"". www.bullionvault.com.

Further reading

- Chimni, B. S. (1987). International Commodity Agreements A Legal Study. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-5420-0.

External links

- Lehman Brothers warns of resources collapse (20 May 2008)

- Askar Akayev's research group predicts the burst of the "Gold Bubble" in April – June 2011

- Latin American Growth in the 21st Century: The 'Commodities Boom' That Wasn't, from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, May 2014

- Ng, Eric (10 July 2013). "Commodities super-cycle is 'taking a break': Runaway prices in commodities markets have ended, but long-term demand for commodities on the mainland is strong". South China Morning Press (SCMP). Retrieved 22 July 2013.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)