2024 in reptile paleontology

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| +... |

This list of fossil reptiles described in 2024 is a list of new taxa of fossil reptiles that were described during the year 2024, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to reptile paleontology that occurred in 2024.

Squamates[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Carvalho & Santucci |

Early Cretaceous (Aptian) |

A member of Polyglyphanodontia. The type species is C. pachysymphysealis. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

In press |

Shaker et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) |

A mosasaur belonging to the subfamily Halisaurinae. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. | ||||

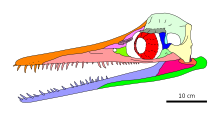

| Khinjaria[3] | Gen. et sp. nov | In press | Longrich et al. | Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) | Ouled Abdoun Basin | A mosasaur belonging to the subfamily Plioplatecarpinae. The type species is K. acuta. | ||

| Segurasaurus[4] | Gen. et comb. nov | Berrocal-Casero et al. | Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) | Tentúgal Formation | A member of Pythonomorpha. The type species is "Carentonosaurus" soaresi. | |||

| Vasuki[5] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Datta & Bajpai | Middle Eocene (Lutetian) | Naredi Formation | A member of Madtsoiidae. The type species is V. indicus. |

| |

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Rivera-Sylva et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Turonian-Coniacian) |

A mosasaur belonging to the subfamily Plioplatecarpinae. Announced in 2023; the final article version was published in 2024. |

Squamate research[edit]

- A study on the biogeography of squamates throughout their evolutionary history, providing evidence of a localized Pangaean origin (Africa, Australia, Eurasia and Sunda) of the squamate crown group in the Jurassic followed by strong regionalization to Eurasia for subsequent Jurassic lineages, is published by Wilenzik, Barger & Pyron (2024).[7]

- Revision of the fossil material of Paleocene lizards from the Walbeck fissure filling (Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) is published by Čerňanský & Vasilyan (2024), who interpret Camptognathosaurus parisiensis as a junior synonym of Glyptosaurus walbeckensis, resulting in a new combination Camptognathosaurus walbeckensis, tentatively assign C. walbeckensis to the family Lacertidae, and interpret fossils of Parasauromalus paleocenicus as belonging to an indeterminate lacertid.[8]

- An iguanian skull from the Paleogene White River Formation (Wyoming, United States), tentatively assigned to the species Aciprion formosum, is interpreted as the oldest and first definitive stem member of Crotaphytidae by Scarpetta (2024); the author also interprets Polrussia mongoliensis as possible member of the crown group of Pleurodonta, Magnuviator ovimonsensis as a possible stem pleurodontan and Afairiguana avius as a possible anole.[9]

- The oldest fossil material of Platecarpus from Europe reported to date, as well as fossil material of Tylosaurus sp, is described from the Santonian localities in the Sougraigne area (Aude Department, France) by Plasse et al. (2024).[10]

- Rempert, Martens & Vinkeles Melchers (2024) describe new fossil material of mosasaurs from the Upper Cretaceous strata in Mississippi (United States), providing evidence of the presence of Mosasaurus hoffmannii during the Maastrichtian and of cf. Platecarpus, an unnamed species of Plioplatecarpus from the Demopolis Chalk and probably of Tylosaurus sp. during the Campanian.[11]

- A study on a skull of a specimen of Plioplatecarpus from the Campanian Bearpaw Shale (Alberta, Canada) preserved with a sclerotic ring is published by Holmes (2024), who interprets Plioplatecarpus as having a stereoscopic vision and capable of tracking quickly moving objects in light-poor conditions.[12]

- Garberoglio, Gómez & Caldwell (2024) describe fossil material of a large-bodied (estimated to be around 8 meters in total length) snake distinct from Titanoboa from the Paleocene Cerrejón Formation (Colombia) interpreted by the authors as an undetermined palaeophiine.[13]

- The first known snake assemblage from early Clarendonian in North America is reported from the Penny Creek Local Fauna (Ash Hollow Formation; Nebraska, United States) by Jacisin & Lawing (2024), who interpret the studied fossils as indicative of a woodland-prairie environment with a permanent stream or river as a local water source.[14]

- ElShafie (2024) presents novel methods which can be used to determine body size from isolated lizard bones and applies these methods to a sample of lizard bones from the Paleogene of North America.[15]

Ichthyosauromorphs[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

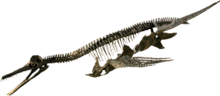

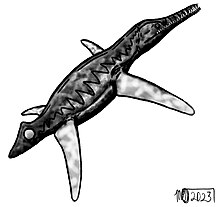

| Argovisaurus[16] | Gen. et sp. nov | Miedema et al. | Middle Jurassic (Bajocian-Bathonian) | Hauptrogenstein Formation | An ichthyosaur closely related to Ophthalmosauria. The type species is A. martafernandezi. |

| ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Lomax et al. |

Late Triassic (Rhaetian) |

Possibly a member of the family Shastasauridae. The type species is I. severnensis. |

Ichthyosauromorph research[edit]

- Sander et al. (2024) describe vertebrae of a member of the genus Cymbospondylus from the Olenekian Vikinghøgda Formation (Svalbard, Norway), interpreted as likely belonging to an animal with a total length between 7.5 m and 9.5 m.[18]

- Putative bone fragments of large-bodied dinosaurs from Rhaetian strata in France, Germany and United Kingdom are reinterpreted as fossil material of large-bodied ichthyosaurs by Perillo & Sander (2024).[19]

- Campos et al. (2024) redescribe the holotype of Myobradypterygius hauthali, interpreting this species as phylogenetically distant from species belonging to the genus Platypterygius, and consider Myobradypterygius to be a distinct genus.[20]

Sauropterygians[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sp. nov |

Hu, Li, & Liu |

|||||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Sachs, Eggmaier & Madzia |

A basal plesiosauroid. The type species is F. brevispinus. |

|||||

| Marambionectes[23] | Gen. et sp. nov | O'Gorman et al. | Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) | Lopez de Bertodano Formation | Antarctica | An elasmosaurid. The type species is M. molinai. | ||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

In press |

Clark, O'Keefe, & Slack |

A polycotylid. The type species is "Dolichorhynchops" bonneri. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. |

|||||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

In press |

Clark, O'Keefe, & Slack |

Late Cretaceous (Turonian) |

A polycotylid. The type species is "Dolichorhynchops" tropicensis. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Clark, O'Keefe, & Slack |

Late Cretaceous (Campanian) |

A polycotylid. The type species is U. specta. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. |

Sauropterygian research[edit]

- A study on tooth wear patterns in Middle and Late Triassic placodonts from Europe, interpreted as suggestive of different diet composition of the studied placodonts (with some taxa unlikely to feed solely on hard-shelled animals), is published by Gere et al. (2024).[25]

- Alhalabi et al. (2024) describe fossil material of an elasmosaurid from the Coniacian-Santonian Rmah Formation (Syria), representing the most complete plesiosaur specimen from the Middle East reported to date and likely the oldest Cretaceous plesiosaur from the Middle East.[26]

- O'Gorman (2024) studies the neck elongation pattern in Elasmosaurus platyurus, taking the taphonomic distortion into account, and presents a new scheme of neck elongation patterns in plesiosaurs with a long neck and small skull.[27]

- Zverkov et al. (2024) redescribe Polycotylus sopozkoi and confirm its status as a distinct species within the genus Polycotylus.[28]

Turtles[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et. sp. nov |

Valid |

Pérez-García & Antunes |

A pancheloniid turtle. The type species is L. emilianoi | |||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Ferreira et al. |

Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene |

A podocnemidid turtle. A giant extinct species of Peltocephalus, represented today only by P. dumerilianus. |

|

Turtle research[edit]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull of Heckerochelys romani is published by Obraztsova, Sukhanov & Danilov (2024).[31]

- Sterli et al. (2024) describe fossil material of a new turtle taxon from the Cenomanian Piedra Clavada Formation (Argentina), with a distinctive morphology indicating that it belongs to a previously unrecognized lineage of turtles, and representing the oldest Late Cretaceous turtle from the southernmost part of South America reported to date.[32]

- Tong et al. (2024) describe new shell material of Phunoichelys thirakhupti and Kalasinemys prasarttongosothi from the Phu Noi site (Thailand), providing new information on the anatomy of the studied turtles.[33]

- Cadena et al. (2024) describe new fossil material of Puentemys mushaisaensis from the Paleogene Arcillolitas de Socha Formation (Boyacá Department, Colombia), expanding known geographical range of the species, and interpret its presence in both Arcillolitas de Socha Formation and the Cerrejón Coal Mine as indicative of connectivity of coastal and inland ecosystems in northern South America during the late Paleocene to early Eocene.[34]

- Sena et al. (2024) study the microstructure of shells of Bauruemys elegans and other members of Pelomedusoides from the Upper Cretaceous and Paleogene strata in southern Brazil, and interpret their findings as consistent with an aquatic to semi-aquatic lifestyle of the studied turtles, as well as supporting the interpretation of the turtle carapace as originating endoskeletally from ribs and vertebral arches.[35]

- Pérez-García, Camilo & Ortega (2024) describe new fossil material of Selenemys lusitanica from the Upper Jurassic Bombarral and Sobral formations (Portugal), providing new information on the shell anatomy of this turtle.[36]

- Spicher, Lyson & Evers (2024) redescribe the anatomy of the skull of Saxochelys gilberti.[37]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull of Allaeochelys libyca is published by Rollot, Evers & Joyce (2024).[38]

- Evers & Al Iawati (2024) describe the anatomy of the skull of Stylemys nebrascensis, and interpret this species as a possible stem-representative of the gopher tortoise lineage.[39]

- Torres et al. (2024) interpret tortoise fossil material from the Late Pleistocene strata in Ecuador as belonging to the sister taxon of the Galápagos tortoises, and interpret the studied fossils as indicating that the ancestors of the Galápagos tortoises evolved large body size before reaching the Galápagos Islands from the South American continent.[40]

- A study on the evolutionary history of turtles from insular Southeast Asia is published by Claude et al. (2024), who confirm that Duboisemys isoclina was an endemic extinct taxon.[41]

Archosauriformes[edit]

Archosaurs[edit]

Other archosauriforms[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Archosauriform research[edit]

- Sharma et al. (2024) describe new proterosuchid material from the Lower Triassic (Induan) Panchet Formation (India), consider fossil material of "Teratosaurus" bengalensis to likely belong to a proterosuchid, and find no evidence for the presence of more than one archosauromorph taxon in the upper Panchet Formation.[42]

- A study on jaw mechanics of Proterochampsa nodosa de Simão-Oliveira et al. (2024), who report that Proterochampsa was able to perform bite forces comparable to those of alligators, but also that its jaws were more susceptible to bending than jaws of alligators, as well as more prone to accumulate stresses resulting from muscle contraction than both alligators and false gharials.[43]

- LePore & McLain (2024) identify a specimen of Machaeroprosopus mccauleyi from the Chinle Formation with a sacrum including a sacralized first caudal vertebra, expanding known sacral count variation in phytosaurs.[44]

- Sander & Wellnitz (2024) describe a phytosaur osteoderm from the Upper Triassic strata in the Bonenburg clay pit (Contorta Beds of the Exter Formation; North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) representing the youngest well-dated phytosaur fossil reported to date, and indicating that phytosaurs survived into the late middle Rhaetian, at most two million years before the end of the Triassic.[45]

Other reptiles[edit]

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Agnolín et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) |

A sphenodontid rhynchocephalian. The type species is A. mineri. Announced in 2023; the final article version will be published in 2024. | ||||

|

Sp. nov |

Jenkins et al. |

Late Triassic |

Chinle Formation | |||||

| Parvosaurus[48] | Gen. et sp. nov | Freisem et al. | Late Triassic (Norian) | Arnstadt Formation | A rhynchocephalian. The type species is P. harudensis. |

| ||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Jung & Sues |

Permian (Kungurian) |

A member of the family Captorhinidae belonging to the subfamily Moradisaurinae. The type species is "Captorhinikos" chozaensis Olson (1954). |

|

Other reptile research[edit]

- A study on the microanatomy and replacement of teeth in mesosaurs is published by Carlisbino et al. (2024).[50]

- New information on the anatomy of the skull of Emeroleter levis is presented by Bazzana-Adams, MacDougall & Fröbisch (2024), who also study the phylogenetic relationships of nycteroleterids.[51]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull and a study on the affinities of Nanoparia luckhoffi is published by Van den Brandt et al. (2024).[52]

- Mooney et al. (2024) describe a skeleton of Captorhinus aguti from the Richards Spur locality (Oklahoma, United States), preserved with integumentary structures interpreted as remnants of the epidermis, and showing surface morphologies of the skin consistent with variation in most extant and extinct reptiles.[53]

- A study on the bone histology of Priosphenodon avelasi, interpreted as indicative of alternation between periods of slow and fast growth, is published by Cavasin, Cerda & Apesteguía (2024).[54]

- Redescription of the skeletal anatomy of Dinocephalosaurus orientalis is published by Spiekman et al. (2024), who interpret D. orientalis as adapted to more open waters than Tanystropheus hydroides, and consider the similarities between Dinocephalosaurus and Tanystropheus to be largely convergent.[55]

- Redescription of Trachelosaurus fischeri, interpreted as the first unambiguous Dinocephalosaurus-like archosauromorph found outside the Guanling Formation, is published by Spiekman et al. (2024), who consider the family Trachelosauridae to be the senior synonym of the family Dinocephalosauridae, and name a new clade of non-crocopodan archosauromorphs Tanysauria.[56]

- Redescription and a study on the affinities of Malerisaurus robinsonae is published by Sengupta, Ezcurra & Bandyopadhyay (2024).[57]

- De-Oliveira et al. (2024) describe new postcranial material of Teyujagua paradoxa from the Lower Triassic Sanga do Cabral Formation (Brazil), providing evidence of a morphology intermediate between early archosauromorphs and proterosuchids.[58]

- Rossi et al. (2024) report that purported soft tissues of the holotype of Tridentinosaurus antiquus are actually manufactured pigment, indicating that the body outline is a forgery and the only real parts of the specimen are the hindlimbs and osteoderms, and consider the validity of the taxon to be doubtful.[59]

Reptiles in general[edit]

- Cawthorne, Whiteside & Benton (2024) describe Late Triassic reptile fossils from the Emborough, Batscombe and Highcroft quarries (Somerset, United Kingdom), including fossil material of a new crocodylomorph taxon similar to Saltoposuchus and other loricatan fossils, an ilium of Pachystropheus rhaeticus (interpreted by the authors as a thalattosaur rather than a choristodere) and fossils of a possible procolophonid, Kuehneosaurus latus, rhynchocephalians, a possible lepidosauromorph similar to Cryptovaranoides microlanius and trilophosaurids.[60]

- A study on the orbit and eye size in fossil archosauromorphs is published by Lautenschlager et al. (2024), who find that the largest eyes relative to the skull length were mostly present in small taxa, that herbivorous species had on average both larger orbits and larger skulls than carnivores, that eyes which were large in absolute terms appeared predominantly in large-sized dinosaurs irrespective of their diet, and that different activity patterns cannot be determined on the basis of orbit size alone.[61]

- A study on the evolution of locomotion in archosauromorph reptiles is published by Shipley et al. (2024), who interpret their findings as indicative of greater range in limb form and locomotor modes of dinosaurs compared to other archosauromorph groups, and argue that the ability to adopt a wider variety of limb forms and modes might have given dinosaurs a competitive advantage over pseudosuchians.[62]

References[edit]

- ^ Carvalho, J. C.; Santucci, R. M. (2023). "A new fossil Squamata from the Quiricó Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Sanfranciscana Basin, Minas Gerais, Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 154. 105717. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105717. S2CID 264138153.

- ^ Shaker, A. A.; Longrich, N. R.; Strougo, A.; Asan, A.; Bardet, N.; Mousa, M. K.; Tantawy, A. A.; Abu El-Kheir, G. A. (2023). "A new species of Halisaurus (Mosasauridae: Halisaurinae) from the lower Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) of the Western Desert, Egypt". Cretaceous Research. 154. 105719. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105719. S2CID 263320383.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Polcyn, Michael J.; Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; Bardet, Nathalie (2024-03-01). "A bizarre new plioplatecarpine mosasaurid from the Maastrichtian of Morocco". Cretaceous Research: 105870. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105870. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Berrocal-Casero, Mélani; Pimentel, Ricardo; Callapez, Pedro Miguel; Barroso-Barcenilla, Fernando; Ozkaya de Juanas, Senay (2024). "On Segurasaurus (Squamata: Pythonomorpha), a New Genus of Lizard from the Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous) of Portugal". Geosciences. 14 (3): 84. doi:10.3390/geosciences14030084. ISSN 2076-3263.

- ^ Datta, Debajit; Bajpai, Sunil (2024-04-18). "Largest known madtsoiid snake from warm Eocene period of India suggests intercontinental Gondwana dispersal". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 8054. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58377-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 38637509.

- ^ Rivera-Sylva, Héctor E.; Longrich, Nicholas R.; Padilla-Gutierrez, José M.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, José Rubén; Escalante-Hernández, Víctor M.; González-Ávila, José G. (2023-11-16). "A new species of Yaguarasaurus (Mosasauridae: Plioplatecarpinae) from the Agua Nueva formation (upper Turonian – ?Lower Coniacian) of Nuevo Leon, Mexico". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 133: 104694. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2023.104694. ISSN 0895-9811. S2CID 265262141.

- ^ Wilenzik, I. V.; Barger, B. B.; Pyron, R. A. (2024). "Fossil-informed biogeographic analysis suggests Eurasian regionalization in crown Squamata during the early Jurassic". PeerJ. 12. e17277. doi:10.7717/peerj.17277.

- ^ Čerňanský, A.; Vasilyan, D. (2024). "Roots of the European Cenozoic ecosystems: lizards from the Paleocene (~MP 5) of Walbeck in Germany". Fossil Record. 27 (1): 159–186. doi:10.3897/fr.27.e109123.

- ^ Scarpetta, S. G. (2024). "A Palaeogene stem crotaphytid (Aciprion formosum) and the phylogenetic affinities of early fossil pleurodontan iguanians". Royal Society Open Science. 11 (1). 221139. Bibcode:2024RSOS...1121139S. doi:10.1098/rsos.221139. PMC 10776235. PMID 38204790.

- ^ Plasse, M.; Valentin, X.; Garcia, G.; Guinot, G.; Bardet, N. (2024). "New remains of Mosasauroidea (Reptilia, Squamata) from the Upper Cretaceous (Santonian) of Aude, southern France". Cretaceous Research. 157. 105823. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15705823P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105823. S2CID 266852358.

- ^ Rempert, T. H.; Martens, B. P.; Vinkeles Melchers, A. P. M. (2024). "New mosasaur remains from the Upper Cretaceous of Mississippi". The Mosasaur. The Journal of the Delaware Valley Paleontological Society. 13: 79–90. doi:10.5281/zenodo.10472410.

- ^ Holmes, R. B. (2024). "Evaluation of the photosensory characteristics of the lateral and pineal eyes of Plioplatecarpus (Squamata, Mosasauridae) based on an exceptionally preserved specimen from the Bearpaw Shale (Campanian, Upper Cretaceous) of southern Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e2335174. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2335174.

- ^ Garberoglio, F. F.; Gómez, R. O.; Caldwell, M. W. (2024). "New record of aquatic snakes (Squamata, Palaeophiidae) from the Paleocene of South America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43 (4). e2305892. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2305892.

- ^ Jacisin, J. J.; Lawing, A. M. (2024). "Fossil snakes of the Penny Creek Local Fauna from Webster County, Nebraska, USA, and the first record of snakes from the Early Clarendonian (12.5-12 Ma) of North America". Palaeontologia Electronica. 27 (1). 27.1.2A. doi:10.26879/1220.

- ^ ElShafie, S. J. (2024). "Body size estimation from isolated fossil bones reveals deep time evolutionary trends in North American lizards". PLOS ONE. 19 (1). e0296318. Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1996318E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0296318. PMC 10769094. PMID 38180961.

- ^ Miedema, Feiko; Bastiaans, Dylan; Scheyer, Torsten M.; Klug, Christian; Maxwell, Erin E. (2024-03-16). "A large new Middle Jurassic ichthyosaur shows the importance of body size evolution in the origin of the Ophthalmosauria". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 24 (1): 34. doi:10.1186/s12862-024-02208-3. ISSN 2730-7182. PMC 10944604. PMID 38493100.

- ^ Lomax, D. R.; de la Salle, P.; Perillo, M.; Reynolds, J.; Reynolds, R.; Waldron, J. F. (2024). "The last giants: New evidence for giant Late Triassic (Rhaetian) ichthyosaurs from the UK". PLOS ONE. 19 (4). e0300289. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0300289. PMC 11023487. PMID 38630678.

- ^ Sander, P. M.; Dederichs, R.; Schaaf, T.; Griebeler, E. M. (2024). "Cymbospondylus (Ichthyopterygia) from the Early Triassic of Svalbard and the early evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs". PalZ. doi:10.1007/s12542-023-00677-3.

- ^ Perillo, M.; Sander, P. M. (2024). "The dinosaurs that weren't: osteohistology supports giant ichthyosaur affinity of enigmatic large bone segments from the European Rhaetian". PeerJ. 12. e17060. doi:10.7717/peerj.17060. PMC 11011611. PMID 38618574.

- ^ Campos, L.; Fernández, M. S.; Bosio, V.; Herrera, Y.; Manzo, A. (2024). "Revalidation of Myobradypterygius hauthali Huene, 1927 and the phylogenetic signal within the ophthalmosaurid (Ichthyosauria) forefins". Cretaceous Research. 157. 105818. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15705818C. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105818. S2CID 266830892.

- ^ Hu, Yi-Wei; Li, Qiang; Liu, Jun (2024-01-05). "A new pachypleurosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of southwestern China and its phylogenetic and biogeographic implications". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 143 (1): 1. Bibcode:2024SwJP..143....1H. doi:10.1186/s13358-023-00292-4. ISSN 1664-2384.

- ^ Sachs, Sven; Eggmaier, Stefan; Madzia, Daniel (2024). "Exquisite skeletons of a new transitional plesiosaur fill gap in the evolutionary history of plesiosauroids". Frontiers in Earth Science. 12. 1341470. Bibcode:2024FrEaS..1241470S. doi:10.3389/feart.2024.1341470.

- ^ O’Gorman, Jose P.; Canale, Juan I.; Bona, Paula; Tineo, David E.; Reguero, Marcelo; Cárdenas, Magalí (2024-12-31). "A new elasmosaurid (Plesiosauria: Sauropterygia) from the López de Bertodano Formation: new data on the evolution of the aristonectine morphology". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 22 (1). doi:10.1080/14772019.2024.2312302. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ a b c Clark, Robert O.; O’Keefe, F. Robin; Slack, Sara E. (2023-12-24). "A new genus of small polycotylid plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of the Western Interior Seaway and a clarification of the genus Dolichorhynchops". Cretaceous Research. 157. 105812. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105812. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 266546582.

- ^ Gere, K.; Nagy, A. L.; Scheyer, T. M.; Werneburg, I.; Ősi, A. (2024). "Complex dental wear analysis reveals dietary shift in Triassic placodonts (Sauropsida, Sauropterygia)". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 143 (1). 4. Bibcode:2024SwJP..143....4G. doi:10.1186/s13358-024-00304-x. PMC 10844150. PMID 38328031.

- ^ Alhalabi, W. A.; Bardet, N.; Sachs, S.; Kear, B. P.; Joude, I. B.; Yazbek, M. K.; Godoy, P. L.; Langer, M. C. (2024). "Recovering lost time in Syria: New Late Cretaceous (Coniacian-Santonian) elasmosaurid remains from the Palmyrides mountain chain". Cretaceous Research. 159. 105871. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105871.

- ^ O'Gorman, J. P. (2024). "How Elongated? The Pattern of Elongation of Cervical Centra of Elasmosaurus platyurus with Comments on Cervical Elongation Patterns among Plesiosauromorphs". Diversity. 16 (2). 106. doi:10.3390/d16020106.

- ^ Zverkov, N. G.; Grigoriev, D. V.; Meleshin, I. A.; Nikiforov, A. V. (2024). "Revision of the plesiosaur Polycotylus sopozkoi from the Southern Urals (Russia) confirms the wide distribution of Polycotylus in the Late Cretaceous of the Northern Hemisphere". Cretaceous Research. 105879. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105879.

- ^ Pérez-García, A; Antunes, M. T. (2024). "A pan-cheloniid turtle from the Middle Miocene of Portugal". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25431. PMID 38482778.

- ^ Ferreira, G. S.; Nasciemento, E. R.; Cadena, E. A.; Cozzuol, M. A.; Farina, B. M.; Pacheco, M. L. A. F.; Rizzutto, M. A.; Langer, M. C. (2024). "The latest freshwater giants: a new Peltocephalus (Pleurodira: Podocnemididae) turtle from the Late Pleistocene of the Brazilian Amazon". Biology Letters. 20 (3). 20240010. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2024.0010. PMC 10932709. PMID 38471564.

- ^ Obraztsova, E. M.; Sukhanov, V. B.; Danilov, I. G. (2024). "Cranial morphology of Heckerochelys romani Sukhanov, 2006, a stem turtle from the Middle Jurassic of European Russia, with implications for the paleoecology of stem turtles". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43 (3). e2293997. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2293997.

- ^ Sterli, J.; Moyano-Paz, D.; Varela, A.; Poiré, D. G.; Iglesias, A. (2024). "An unusual circumpolar turtle (Testudinata: Testudines) from the earliest Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". Ameghiniana. 61 (1): 34–44. doi:10.5710/AMGH.23.01.2024.3583.

- ^ Tong, H.; Chanthasit, P.; Naksri, W.; Suteethorn, S.; Claude, J. (2024). "New material of turtles from the Upper Jurassic of Phu Noi, NE Thailand: Phylogenetic implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 109 (4). 102656. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2023.102656.

- ^ Cadena, E.-A.; Benítez, B.; Apen, F. E.; Crowley, J. L.; Cottle, J.; Jaramillo, C. (2024). "Wider paleogeographical distribution of bothremydid turtles in northern South America during the Paleocene–Eocene". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. 24 (1): 149–163. doi:10.5710/PEAPA.14.02.2024.499.

- ^ Sena, M. V. A.; Simbras, F. M.; Sayão, J. M.; Oliveira, G. R. (2024). "Insights into the shell microstructure of Bauruemys elegans and other pelomedusoids from the Cretaceous and Paleogene in Southern Brazil, including first Testudines material from Jangada Roncador Village, Paraná Basin". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 104886. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2024.104886.

- ^ Pérez-García, A.; Camilo, B.; Ortega, F. (2024). "New data on the shell anatomy of Selenemys lusitanica, the oldest known pleurosternid turtle in Europe". Journal of Iberian Geology. doi:10.1007/s41513-024-00230-4.

- ^ Spicher, G. E.; Lyson, T. R.; Evers, S. W. (2024). "Updated cranial and mandibular description of the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) baenid turtle Saxochelys gilberti based on micro-computed tomography scans and new information on the holotype-shell association". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 143 (1). 2. Bibcode:2024SwJP..143....2S. doi:10.1186/s13358-023-00301-6. PMC 10805913. PMID 38274637.

- ^ Rollot, Y.; Evers, S. W.; Joyce, W. G. (2024). "A digital redescription of the Middle Miocene (Langhian) carettochelyid turtle Allaeochelys libyca". Fossil Record. 27 (1): 13–28. Bibcode:2024FossR..27...13R. doi:10.3897/fr.27.115046.

- ^ Evers, S. W.; Al Iawati, Z. (2024). "Digital skull anatomy of the Oligocene North American tortoise Stylemys nebrascensis with taxonomic comments on the species and comparisons with extant testudinids of the Gopherus–Manouria clade". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 143 (1). 12. doi:10.1186/s13358-024-00311-y. PMC 10914918. PMID 38455968.

- ^ Torres, F.; Huang, E. J.; Román-Carrion, J. L.; Bever, G. S. (2024). "New insights into the origin of the Galápagos tortoises with a tip-dated analysis of Testudinidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43 (4). e2313615. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2313615.

- ^ Claude, J.; Tong, H.; van der Geer, A.; Antoine, P.-O.; Reyes, M.; de Vos, J.; Ingicco, T. (2024). "The origin of the Malesian fossil turtle diversity: Fossil versus molecular data". Annales de Paléontologie. 110 (1). 102665. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2024.102665.

- ^ Sharma, K. M.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Tiwari, R. P.; Patnaik, R.; Singh, Y. P.; Singh, N. A. (2024). "Additional information on the archosauriforms from the lowermost Triassic Panchet Formation of India and the affinities of "Teratosaurus(?) bengalensis"". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. 24 (1): 97–107. doi:10.5710/PEAPA.26.02.2024.496.

- ^ de Simão-Oliveira, D.; dos Santos, T.; Pinheiro, F. L.; Pretto, F. A. (2024). "Assessing the adductor musculature and jaw mechanics of Proterochampsa nodosa (Archosauriformes: Proterochampsidae) through finite element analysis". The Anatomical Record. 307 (4): 1300–1314. doi:10.1002/ar.25380. PMID 38240352. S2CID 267039891.

- ^ LePore, C. N.; McLain, M. A. (2024). "Variation in the sacrum of phytosaurs: New evidence from a partial skeleton of Machaeroprosopus mccauleyi". Journal of Anatomy. doi:10.1111/joa.14007. PMID 38284134.

- ^ Sander, P. M.; Wellnitz, P. W. (2024). "A phytosaur osteoderm from a late middle Rhaetian bone bed of Bonenburg (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany): Implications for phytosaur extinction". Fossil Record. 27 (1): 147–158. doi:10.3897/fr.27.e114601.

- ^ Agnolín, F. L.; Aranciaga Rolando, A. M.; Chimento, N. R.; Novas, F. E. (2023). "New small reptile remains from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia increase morphological diversity of sphenodontids (Lepidosauria)". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 135: 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2023.09.007. S2CID 264082428.

- ^ Jenkins, K. M.; Bell, C. J.; Hancox, P. J.; Lewis, P. J. (2024). "A new species of Palacrodon and a unique form of tooth attachment in reptiles". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e2328658. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2328658.

- ^ Freisem, Lisa S.; Müller, Johannes; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Sobral, Gabriela (2024-03-16). "A new sphenodontian (Diapsida: Lepidosauria) from the Upper Triassic (Norian) of Germany and its implications for the mode of sphenodontian evolution". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 24 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/s12862-024-02218-1. ISSN 2730-7182. PMC 10944618. PMID 38493125.

- ^ Jung, J. P.; Sues, H.-D. (2024). "Reassessment of 'Captorhinikos' chozaensis, an early Permian (Cisuralian: Kungurian) captorhinid reptile from Oklahoma and north-central Texas". Journal of Paleontology: 1–13. doi:10.1017/jpa.2023.85.

- ^ Carlisbino, T.; Farias, B. D. M.; Sedor, F. A.; Soares, M. B.; Schultz, C. L. (2024). "Replacement tooth in mesosaurs and new data on dental microanatomy and microstructure". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25442. PMID 38581219.

- ^ Bazzana-Adams, K. D; MacDougall, M. J.; Fröbisch, J. (2024). "Cranial anatomy of Emeroleter levis and the phylogeny of Nycteroleteridae". PLOS ONE. 19 (4). e0298216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0298216.

- ^ Van den Brandt, M. J.; Cisneros, J. C.; Abdala, F.; Boyarinova, E. I.; Golubev, V. K.; Norton, L. A.; Radermacher, V. J.; Rubidge, B. S. (2024). "Cranial osteology and a new diagnosis of the late Permian pareiasaur Nanoparia luckhoffi (Broom, 1936) from the Karoo Basin of South Africa, and a consolidated pareiasaurian phylogeny". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 26 (4): 288–314. doi:10.4072/rbp.2023.4.04.

- ^ Mooney, E. D.; Maho, T.; Philp, R. P.; Bevitt, J. J.; Reisz, R. R. (2024). "Paleozoic cave system preserves oldest-known evidence of amniote skin". Current Biology. 34 (2): 417–426.e4. Bibcode:2024CBio...34E.417M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2023.12.008. PMID 38215745.

- ^ Cavasin, S. A.; Cerda, I. A.; Apesteguía, S. (2024). "Bone microstructure of the sphenodont rhynchocephalian Priosphenodon avelasi and its paleobiological implications". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 69 (1): 29–38. doi:10.4202/app.01071.2023.

- ^ Spiekman, S. N. F.; Wang, W.; Zhao, L.; Rieppel, O.; Fraser, N. C.; Li, C. (2024). "Dinocephalosaurus orientalis Li, 2003: a remarkable marine archosauromorph from the Middle Triassic of southwestern China". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: 1–33. doi:10.1017/S175569102400001X.

- ^ Spiekman, S. N. F.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Rytel, A.; Wang, W.; Mujal, E.; Buchwitz, M.; Schoch, R. R. (2024). "A redescription of Trachelosaurus fischeri from the Buntsandstein (Middle Triassic) of Bernburg, Germany: the first European Dinocephalosaurus-like marine reptile and its systematic implications for long-necked early archosauromorphs". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 143 (1). 10. doi:10.1186/s13358-024-00309-6.

- ^ Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2024). "The redescription of Malerisaurus robinsonae (Archosauromorpha: Allokotosauria) from the Upper Triassic lower Maleri Formation, Pranhita-Godavari Basin, India". The Anatomical Record. 307 (4): 1315–1365. doi:10.1002/ar.25392. PMID 38278769. S2CID 267268073.

- ^ De-Oliveira, T. M.; Da Silva, J. L.; Kerber, L.; Pinheiro, F. L. (2024). "The postcranial skeleton of Teyujagua paradoxa (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) from the early Triassic of South America". The Anatomical Record. 307 (4): 752–775. doi:10.1002/ar.25391. PMID 38259049. S2CID 267094432.

- ^ Rossi, V.; Bernardi, M.; Fornasiero, M.; Nestola, N.; Unitt, R.; Castelli, S.; Kustatscher, E. (2024). "Forged soft tissues revealed in the oldest fossil reptile from the early Permian of the Alps". Palaeontology. 67 (1). e12690. Bibcode:2024Palgy..6712690R. doi:10.1111/pala.12690.

- ^ Cawthorne, M.; Whiteside, D. I.; Benton, M. J. (2024). "Latest Triassic terrestrial microvertebrate assemblages from caves on the Mendip palaeoisland, S.W. England, at Emborough, Batscombe and Highcroft Quarries". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 135: 105–130. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2023.12.003.

- ^ Lautenschlager, S.; Aston, R. F.; Baron, J. L.; Boyd, J. R.; Bridger, H. W. L.; Carmona, V. E. T.; Ducrey, T.; Eccles, O.; Gall, M.; Jones, S. A.; Laker-McHugh, H.; Lawrenson, D. J.; Mascarenhas, K. J.; McSchnutz, E.; Quinn, J. D.; Robson, T. E.; Stöhr, P. W.; Strahl, E. J.; Tokeley, R. R.; Weston, F.; Wallace, K. J.; Whitehouse, T.; Bird, C. M.; Dunne, E. M. (2024). "Orbit size and estimated eye size in dinosaurs and other archosaurs and their implications for the evolution of visual capabilities". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43 (3). e2295518. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2295518.

- ^ Shipley, A. E.; Elsler, A.; Singh, S. A.; Stubbs, T. L.; Benton, M. J. (2024). "Locomotion and the early Mesozoic success of Archosauromorpha". Royal Society Open Science. 11 (2). 231495. Bibcode:2024RSOS...1131495S. doi:10.1098/rsos.231495. PMC 10846959. PMID 38328568.