PANDAS

| PANDAS | |

|---|---|

| |

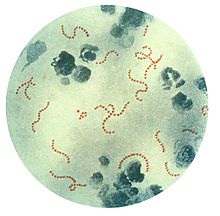

| Streptococcus pyogenes (stained red), a common group A streptococcal bacterium. PANDAS is hypothesized to be an autoimmune condition in which the body's own antibodies to streptococci attack the basal ganglion cells of the brain, by a concept known as molecular mimicry. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) is a hypothesis that there exists a subset of children with rapid onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or tic disorders and these symptoms are caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections.[1] The proposed link between infection and these disorders is that an initial autoimmune reaction to a GABHS infection produces antibodies that interfere with basal ganglia function, causing symptom exacerbations. It has been proposed that this autoimmune response can result in a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms.[2][3] The PANDAS hypothesis was based on observations in clinical case studies at the US National Institutes of Health and in subsequent clinical trials where children appeared to have dramatic and sudden OCD exacerbations and tic disorders following infections.[4]

OCD and tic disorders are hypothesized to arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process.[5][6][7] The PANDAS hypothesis is unconfirmed and unsupported by data, and two new categories have been proposed: PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome) and CANS (childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndrome).[6][7] The CANS/PANS hypotheses include different possible mechanisms underlying acute-onset neuropsychiatric conditions, but do not exclude GABHS infections as a cause in a subset of individuals.[6][7] PANDAS, PANS and CANS are the focus of clinical and laboratory research but remain unproven.[5][6][7] Whether PANDAS is a distinct entity differing from other cases of tic disorders or OCD is debated.[8][9][10][11] PANDAS is a subset of the pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) hypothesis.[12]

Characteristics

In addition to an OCD or tic disorder diagnosis, children may have other symptoms associated with exacerbations such as emotional lability, enuresis, anxiety, and deterioration in handwriting.[1] In the PANDAS model, this abrupt onset is thought to be preceded by a strep throat infection. As the clinical spectrum of PANDAS appears to resemble that of Tourette's syndrome, some researchers hypothesized that PANDAS and Tourette's may be associated; this idea is controversial and a focus for current research.[3][13][14][10][11]

Mechanism

The PANDAS diagnosis and the hypothesis that symptoms in this subgroup of patients are caused by infection are controversial.[1][3][14][15][16][17]

Whether the group of patients diagnosed with PANDAS have developed tics and OCD through a different mechanism (pathophysiology) than seen in other people diagnosed with Tourette syndrome is unclear.[10][11][15][18] Researchers are pursuing the hypothesis that the mechanism is similar to that of rheumatic fever, an autoimmune disorder triggered by streptococcal infections, where antibodies attack the brain and cause neuropsychiatric conditions.[1]

The molecular mimicry hypothesis is a proposed mechanism for PANDAS:[19] this hypothesis is that antigens on the cell wall of the streptococcal bacteria are similar in some way to the proteins of the heart valve, joints, or brain. Because the antibodies set off an immune reaction which damages those tissues, the child with rheumatic fever can get heart disease (especially mitral valve regurgitation), arthritis, and/or abnormal movements known as Sydenham's chorea or "St. Vitus' Dance".[20] In a typical bacterial infection, the body produces antibodies against the invading bacteria, and the antibodies help eliminate the bacteria from the body. In some rheumatic fever patients, autoantibodies may attack heart tissue, leading to carditis, or cross-react with joints, leading to arthritis.[19] In PANDAS, it is believed that tics and OCD are produced in a similar manner. One part of the brain that may be affected in PANDAS is the basal ganglia, which is believed to be responsible for movement and behavior. It is thought that similar to Sydenham's chorea, the antibodies cross-react with neuronal brain tissue in the basal ganglia to cause the tics and OCD that characterize PANDAS.[1][21] Studies neither disprove nor support this hypothesis: the strongest supportive evidence comes from a controlled study of 144 children (Mell et al., 2005), but prospective longitudinal studies have not produced conclusive results.[15]

Diagnosis

According to Lombroso and Scahill, 2008, "(f)ive diagnostic criteria were proposed for PANDAS: (1) the presence of a tic disorder and/or OCD consistent with DSM-IV; (2) prepubertal onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms; (3) a history of a sudden onset of symptoms and/or an episodic course with abrupt symptom exacerbation interspersed with periods of partial or complete remission; (4) evidence of a temporal association between onset or exacerbation of symptoms and a prior streptococcal infection; and (5) adventitious movements (e.g., motoric hyperactivity and choreiform movements) during symptom exacerbation".[19] The children, originally described by Swedo et al. in 1998, usually have dramatic, "overnight" onset of symptoms, including motor or vocal tics, obsessions, and/or compulsions.[22] Some studies have supported acute exacerbations associated with streptococcal infections among clinically defined PANDAS subjects (Murphy and Pichichero, 2002; Giulino et al., 2002); others have not (Luo et al., 2004; Perrin et al., 2004).[1]

Concerns have been raised that PANDAS may be overdiagnosed, as a significant number of patients diagnosed with PANDAS by community physicians did not meet the criteria when examined by specialists, suggesting the PANDAS diagnosis is conferred by community physicians without conclusive evidence.[15][23]

Classification

PANDAS is hypothesized to be an autoimmune disorder that results in a variable combination of tics, obsessions, compulsions, and other symptoms that may be severe enough to qualify for diagnoses such as chronic tic disorder, OCD, and Tourette syndrome (TS or TD). The cause is thought to be akin to that of Sydenham's chorea, which is known to result from childhood Group A streptococcal (GAS) infection leading to the autoimmune disorder acute rheumatic fever of which Sydenham's is one manifestation. Like Sydenham's, PANDAS is thought to involve autoimmunity to the brain's basal ganglia. Unlike Sydenham's, PANDAS is not associated with other manifestations of acute rheumatic fever, such as inflammation of the heart.[4] Pichechero notes that PANDAS has not been validated as a disease classification, for several reasons. Its proposed age of onset and clinical features reflect a particular group of patients chosen for research studies, with no systematic studies of the possible relationship of GAS to other neurologic symptoms. There is controversy over whether its symptom of choreiform movements is distinct from the similar movements of Sydenham's. It is not known whether the pattern of abrupt onset is specific to PANDAS. Finally, there is controversy over whether there is a temporal relationship between GAS infections and PANDAS symptoms.[4]

To establish that a disorder is an autoimmune disorder, Witebsky criteria require

- that there be a self-reactive antibody,

- that a particular target for the antibody is identified (autoantigen)

- that the disorder can be caused in animals and

- that transferring antibodies from one animal to another triggers the disorder (passive transfer).[24]

In addition, to show that a microorganism causes the disorder, the Koch postulates would require one show that the organism is present in all cases of the disorder, that the organism can be extracted from those with the disorder and be cultured, that transferring the organism into healthy subjects causes the disorder, and the organism can be reisolated from the infected party.[24] Giovanonni notes that the Koch postulates cannot be used in the case of postinfection disorders (such as PANDAS and SC) because the organism may no longer be present when symptoms emerge, multiple organisms may cause the symptoms, and the symptoms may be a rare reaction to a common pathogen.[24]

Treatment

Treatment for children suspected of PANDAS is generally the same as the standard treatments for TS and OCD.[2][25][18] These include cognitive behavioral therapy and medications to treat OCD such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs);[25][18] and "conventional therapy for tics".[2]

A controlled study (Garvey, Perlmutter et al. 1999) of prophylactic antibiotic treatment of 37 children found that penicillin V did not prevent GABHS infections or exacerbation of other symptoms; however, compliance was an issue in this study. A later study (Snider, Lougee, et al., 2005) found that penicillin and azithromycin decreased infections and symptom exacerbation. The sample size, controls, and methodology of that study were criticized.[1] Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman (2010) say, "The use of prophylactic antibiotics to treat PANDAS has become widespread in the community, although the evidence supporting their use is equivocal. The safety and efficacy of antibiotic therapy for patients meeting the PANDAS criteria needs to be determined in carefully designed trials";[25] de Oliveira and Pelajo (2009) say that because most studies to date have "methodologic issues, including small sample size, retrospective reports of the baseline year, and lack of an adequate placebo arm ... it is recommended to treat these patients only with conventional therapy".[2]

Evidence is insufficient to determine if tonsillectomy is effective.[2]

Experimental treatments

Prophylactic antibiotic treatments for tics and OCD are experimental[8] and controversial;[15] overdiagnosis of PANDAS may have led to overuse of antibiotics to treat tics or OCD in the absence of active infection.[15]

A single study of PANDAS patients showed efficacy of immunomodulatory therapy (intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasma exchange) to symptoms,[1] but these results are unreplicated by independent studies as of 2010.[19][15] Kalra and Swedo wrote in 2009, "Because IVIG and plasma exchange both carry a substantial risk of adverse effects, use of these modalities should be reserved for children with particularly severe symptoms and a clear-cut PANDAS presentation.[18] The US National Institutes of Health and American Academy of Neurology 2011 guidelines say there is "inadequate data to determine the efficacy of plasmapheresis in the treatment of acute OCD and tic symptoms in the setting of PANDAS" and "insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of plasmapheresis in the treatment of acute OCD and tic symptoms in the setting of PANDAS", adding that the investigators in the only study of plasmapherisis were not blind to the results.[13] The Medical Advisory Board of the Tourette Syndrome Association said in 2006 that experimental treatments based on the autoimmune theory such as IVIG or plasma exchange should not be undertaken outside of formal clinical trials.[26] The American Heart Association's 2009 guidelines state that, as PANDAS is an unproven hypothesis and well-controlled studies are not yet available, they do "not recommend routine laboratory testing for GAS to diagnose, long-term antistreptococcal prophylaxis to prevent, or immunoregulatory therapy (e.g., intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange) to treat exacerbations of this disorder".[27]

Society and culture

The debate surrounding the PANDAS hypothesis has societal implications; the media and the Internet have played a role in the PANDAS controversy.[25][28] Swerdlow (2005) summarized the societal implications of the hypothesis, and the role of the Internet in the controversy surrounding the PANDAS hypothesis:

... perhaps the most controversial putative TS trigger is exposure to streptococcal infections. The ubiquity of strep throats, the tremendous societal implications of over-treatment (e.g., antibiotic resistance or immunosuppressant side effects) versus medical implications of under-treatment (e.g., potentially irreversible autoimmune neurologic injury) are serious matters. With the level of desperation among Internet-armed parents, this controversy has sparked contentious disagreements, too often lacking both objectivity and civility.[28]

Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman (2010) also discussed the influence of the media and the Internet in a paper that proposed a "way forward":

The potential link between common childhood infections and lifelong neuropsychiatric disorders is among the most tantalizing and clinically relevant concepts in modern neuroscience ... The link may be most relevant in this group of disorders collectively described as PANDAS. Of concern, public awareness has outpaced our scientific knowledge base, with multiple magazine and newspaper articles and Internet chat rooms calling this issue to the public's attention. Compared with ~ 200 reports listed on Medline—many involving a single patient, and others reporting the same patients in different papers, with most of these reporting on subjects who do not meet the current PANDAS criteria—there are over 100,000 sites on the Internet where the possible Streptococcus–OCD–TD relationship is discussed. This gap between public interest in PANDAS and conclusive evidence supporting this link calls for increased scientific attention to the relationship between GAS and OCD/tics, particularly examining basic underlying cellular and immune mechanisms.[25]

History

Susan Swedo first described the entity in 1998.[22] In 2008 Lombroso and Scahill described five diagnostic criteria for PANDAS.[19] Revised criteria and guidelines for PANDAS was established by the National Institute of Mental Health in 2012 and updated in 2017.[29][12]

Research directions

In a 2010 paper calling for "a way forward", Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman said: "It is time for the National Institutes of Health, in combination with advocacy and professional organizations, to convene a panel of experts not to debate the current data, but to chart a way forward. For now we have only to offer our standard therapies in treating OCD and tics, but one day we may have evidence that also allows us to add antibiotics or other immune-specific treatments to our armamentarium."[25] A 2011 paper by Singer proposed a new, "broader concept of childhood acute neuropsychiatric symptoms (CANS)", removing some of the PANDAS criteria in favor or requiring only acute-onset. Singer said there were "numerous causes for CANS", which was proposed because of the "inconclusive and conflicting scientific support" for PANDAS, including "strong evidence suggesting the absence of an important role for GABHS, a failure to apply published [PANDAS] criteria, and a lack of scientific support for proposed therapies".[30]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Moretti G, Pasquini M, Mandarelli G, Tarsitani L, Biondi M (2008). "What every psychiatrist should know about PANDAS: a review". Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 4 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-4-13. PMC 2413218. PMID 18495013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e de Oliveira SK, Pelajo CF (March 2010). "Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infection (PANDAS): a Controversial Diagnosis". Curr Infect Dis Rep. 12 (2): 103–9. doi:10.1007/s11908-010-0082-7. PMID 21308506. S2CID 30969859.

- ^ a b c Boileau B (2011). "A review of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 13 (4): 401–11. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/bboileau. PMC 3263388. PMID 22275846.

- ^ a b c d Pichichero ME (2009). "The PANDAS syndrome". Hot Topics in Infection and Immunity in Children V. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 634. Springer. pp. 205–16. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79838-7_17. ISBN 978-0-387-79837-0. PMID 19280860.

PANDAS is not yet a validated nosological construct.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Dale RC (December 2017). "Tics and Tourette: a clinical, pathophysiological and etiological review". Curr Opin Pediatr (Review). 29 (6): 665–673. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000546. PMID 28915150. S2CID 13654194.

- ^ a b c d Marazziti D, Mucci F, Fontenelle LF (July 2018). "Immune system and obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychoneuroendocrinology (Review). 93: 39–44. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.013. PMID 29689421. S2CID 13681480.

- ^ a b c d Zibordi F, Zorzi G, Carecchio M, Nardocci N (March 2018). "CANS: Childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndromes". Eur J Paediatr Neurol (Review). 22 (2): 316–320. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.01.011. PMID 29398245.

- ^ a b Shulman ST (February 2009). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS): update". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 21 (1): 127–30. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32831db2c4. PMID 19242249. S2CID 37434919.

Despite continued research in the field, the relationship between GAS and specific neuropsychiatric disorders (PANDAS) remains elusive.

- ^ Maia TV, Cooney RE, Peterson BS (2008). "The neural bases of OCD in children and adults". Dev. Psychopathol. 20 (4): 1251–83. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000606. PMC 3079445. PMID 18838041.

- ^ a b c Robertson MM (February 2011). "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment" (PDF). Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 72 (2): 100–7. doi:10.12968/hmed.2011.72.2.100. PMID 21378617.

- ^ a b c Singer HS (2011). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 100. pp. 641–57. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00046-X. ISBN 9780444520142. PMID 21496613.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Guidelines published for treating PANS/PANDAS". www.nimh.nih.gov. NIMH.

- ^ a b Cortese I, Chaudhry V, So YT, Cantor F, Cornblath DR, Rae-Grant A (January 2011). "Evidence-based guideline update: Plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 76 (3): 294–300. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318207b1f6. PMC 3034395. PMID 21242498.

- ^ a b Felling RJ, Singer HS (August 2011). "Neurobiology of tourette syndrome: current status and need for further investigation". J. Neurosci. 31 (35): 12387–95. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0150-11.2011. PMC 6703258. PMID 21880899.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leckman JF, Denys D, Simpson HB, et al. (June 2010). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review of the diagnostic criteria and possible subtypes and dimensional specifiers for DSM-V" (PDF). Depress Anxiety. 27 (6): 507–27. doi:10.1002/da.20669. PMC 3974619. PMID 20217853.

- ^ Kurlan R, Kaplan EL (Apr 2004). "The pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS) etiology for tics and obsessive–compulsive symptoms: hypothesis or entity? Practical considerations for the clinician" (PDF). Pediatrics. 113 (4): 883–86. doi:10.1542/peds.113.4.883. PMID 15060240.

- ^ Shprecher D, Kurlan R (January 2009). "The management of tics". Mov. Disord. 24 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1002/mds.22378. PMC 2701289. PMID 19170198.

- ^ a b c d Kalra SK, Swedo SE (April 2009). "Children with obsessive-compulsive disorder: are they just "little adults"?". J. Clin. Invest. 119 (4): 737–46. doi:10.1172/JCI37563. PMC 2662563. PMID 19339765.

- ^ a b c d e f Lombroso PJ, Scahill L (2008). "Tourette syndrome and obsessive–compulsive disorder". Brain Dev. 30 (4): 231–7. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2007.09.001. PMC 2291145. PMID 17937978.

- ^ Bonthius D, Karacay B (2003). "Sydenham's chorea: not gone and not forgotten". Semin Pediatr Neurol. 10 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1016/S1071-9091(02)00004-9. PMID 12785743.

- ^ a b Leckman JF, Bloch MH, King RA (2009). "Symptom dimensions and subtypes of obsessive–compulsive disorder: a developmental perspective" (PDF). Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 11 (1): 21–33. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/jfleckman. PMC 3181902. PMID 19432385. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ^ a b Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al. (February 1998). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases". Am J Psychiatry. 155 (2): 264–71. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.2.264 (inactive 2021-01-20). PMID 9464208.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link) - ^ Shulman ST (February 2009). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS): update". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 21 (1): 127–30. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32831db2c4. PMID 19242249. S2CID 37434919.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-source=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Giavannoni G (2006). PANDAS: overview of the hypothesis. Vol. 99. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 159–65. ISBN 978-0-7817-9970-6. PMID 16536362.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Murphy TK, Kurlan R, Leckman J (August 2010). "The immunobiology of Tourette's disorder, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with Streptococcus, and related disorders: a way forward". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 20 (4): 317–31. doi:10.1089/cap.2010.0043. PMC 4003464. PMID 20807070.

- ^ Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM, et al. (April 2006). "Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome". NeuroRx. 3 (2): 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.009. PMC 3593444. PMID 16554257.

- ^ Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. (March 2009). "Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute Streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics". Circulation. 119 (11): 1541–51. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.191959. PMID 19246689.

- ^ a b Swerdlow NR (September 2005). "Tourette syndrome: current controversies and the battlefield landscape". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 5 (5): 329–31. doi:10.1007/s11910-005-0054-8. PMID 16131414. S2CID 26342334.

- ^ "Revised Treatment Guidelines Released for Pediatric Acute Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS/PANDAS)". www.liebertpub.com. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers.

- ^ Singer HS, Gilbert DL, Wolf DS, Mink JW, Kurlan R (December 2011). "Moving from PANDAS to CANS". J Pediatr. 160 (5): 725–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.040. PMID 22197466.