Irreligion in Mexico

Irreligion in Mexico refers to atheism, deism, religious skepticism, secularism, and secular humanism in Mexican society, which was a confessional state after independence from Imperial Spain. The first political constitution of the Mexican United States enacted in 1824, stipulated that Roman Catholicism was the national religion in perpetuity, and prohibited any other religion.[1] Moreover, since 1857, by law, Mexico has had no official religion;[2] as such, anti-clerical laws meant to promote a secular society, contained in the 1857 Constitution of Mexico and in the 1917 Constitution of Mexico limited the participation in civil life of Roman Catholic organizations, and allowed government intervention to religious participation in politics.

In 1992, the Mexican constitution was amended to eliminate the restrictions, and granted legal status to religious organizations, limited property rights, voting rights to ministers, and allowing a greater number of priests in Mexico.[3] Nonetheless, the principles of the Separation of Church and State remain; members of religious orders (priests, nuns, ministers, et al.) cannot hold elected office, the federal government cannot subsidize any religious organization, and religious orders, and their officers, cannot teach in the public school system.

Historically, the Roman Catholic Church dominated the religious, political, and cultural landscapes of the nation; yet, the Catholic News Agency said that there exists a great, secular community of atheists, intellectuals and irreligious people,[4][5] reaching 10% according to recent polls by religious agencies.[6]

Religion and politics

This section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (November 2020) |

Since the Spanish Conquest (1519–21), the Roman Catholic Church has held prominent social and political positions concerning the moral education of Mexicans; the ways that virtues and morals are to be socially implemented; and thus contributed to the Mexican cultural identity. Such cultural immanence was confirmed in the nation's first political constitution, which formally protected Catholicism; thus, Article 3 of the 1824 Constitution of Mexico established that:

The Religion of the Mexican Nation, is, and will be perpetually, the Roman Catholic Apostolic. The Nation will protect it by wise and just laws, and prohibit the exercise of any other whatever". (Article 3 of the Federal Constitution of the Mexican United States, 1824)[1]

For most of Mexico's 300 years as the Imperial Spanish colony of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (1519–1821), the Roman Catholic Church was an active political actor in colonial politics. In the early period of the Mexican nation, the vast wealth and great political influence of the Church spurred a powerful anti-clerical movement, which found political expression in the Liberal party. Yet, during the middle of the 19th century, there were reforms limiting the political power of the Mexican Catholic Church. In response, the Church supported seditious Conservative rebels to overthrow the anti-clerical Liberal government of President Benito Juárez; and so welcomed the anti-Juárez French intervention in Mexico (1861), which established the military occupation of Mexico by the Second French Empire, of Emperor Napoleon III.[8]

About the Mexican perspective of the actions of the Roman Catholic Church, the Mexican Labour Party activist Robert Haberman said:

By the year 1854, The Church gained possession of about two-thirds of all the lands of Mexico, almost every bank, and every large business. The rest of the country was mortgaged to the Church. Then came the revolution of 1854, led by Benito Juárez. It culminated in the Constitution of 1857, which secularised the schools and confiscated Church property. All the churches were nationalised, many of them were turned into schools, hospitals, and orphan asylums. Civil marriages were obligatory. Pope Pius IX immediately issued a mandate against the Constitution, and called upon all Catholics of Mexico to disobey it. Ever since then, the clergy has been fighting to regain its lost temporal power and wealth. (The Necessity of Atheism, p. 154)[9]

At the turn of the 19th century, the collaboration of the Mexican Catholic Church with the Porfiriato, the 35-year dictatorship of General Porfirio Díaz, earned the Mexican clergy the ideological enmity of the revolutionary victors of the Mexican Revolution (1910–20); thus, the Mexican Constitution of 1917 legislated severe social and political, economic and cultural restrictions upon the Catholic Church in the Republic of Mexico. Historically, the 1917 Mexican Constitution was the first political constitution to explicitly legislate the social and civil rights of the people; and served as constitutional model for the Weimar Constitution of 1919 and the Russian Constitution of 1918.[10][11][12][13] Nevertheless, like the Spanish Constitution of 1931, it has been characterized as being hostile to religion.[14]

The Constitution of 1917 proscribed the Catholic clergy from working as teachers and as instructors in public and private schools; established State control over the internal matters of the Mexican Catholic Church; nationalized all Church property; proscribed religious orders; forbade the presence in Mexico of foreign-born priests; granted each state of the Mexican republic the power to limit the number of, and to eliminate, priests in its territory; disenfranchised priests of the civil rights to vote, and to hold elected office; banned Catholic organizations that advocated public policy; forbade religious publications from editorial commentary about public policy; proscribed the clergy from wearing clerical garb in public; and voided the right to trial of any Mexican citizen who violated anti-clerical laws.[15][16]

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), the national rancour provoked by the history of the Catholic Church's mistreatment of Mexicans was aggravated by the collaboration of the Mexican High Clergy with the pro–U.S. dictatorship (1913–14) of General Victoriano Huerta, "The Usurper" of the Mexican Presidency; thus, anti-clerical laws were integral to the Mexican Constitution of 1917, in order to establish a secular society.[17][18][19][20][21] In the 1920s, the enforcement of the Constitutional anti-clerical laws, by the Mexican Federal Government, provoked the Cristero Rebellion (1926–29), the clerically-abetted armed revolt of Catholic peasants, known as "The Christers" (Los cristeros). The social and political tensions between the Catholic Church and the Mexican State lessened after 1940, but the Constitutional restrictions remained the law of the land, although their enforcement became progressively lax. The Government established diplomatic relations with the Holy See during the administration of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988–94), and the Government lifted almost all restrictions on the Catholic Church in 1992. That year the Government ratified its informal policy of not enforcing most legal controls on religious groups by, among other things, granting religious groups legal status, conceding them limited property rights, and lifting restrictions on the number of priests in the country. However, the law continues to mandate strict restrictions on the church and bars the clergy from holding public office, advocating partisan political views, supporting political candidates, or opposing the laws or institutions of the State. The Church's ability to own and operate mass media is also limited. Indeed, after the creation of the Constitution the Catholic Church has been acutely hostile towards the Mexican government. As Laura Randall in his book Changing Structure of Mexico points out, most of the conflicts between citizens and religious leaders lie in the Church's overwhelming lack of understanding of the role of the state's laicism. "The inability of the Mexican Catholic Episcopate to understand the modern world translates into a distorted conception of the secular world and the lay state. Evidently, perceiving the state as anti-religious (or rather, anti-clerical) is the result of 19th-century struggles that imbued the state with anti-religious and anti-clerical tinges in Latin American countries, much to the Catholic Church's chagrin. Defining laicist education as a 'secular religion' that is also 'imposed and intolerant' is the clearest evidence of episcopal intransigence."[22] Others, however see the Mexican state's anticlericalism differently. Recent President Vicente Fox stated, "After 1917, Mexico was led by anti-Catholic Freemasons who tried to evoke the anticlerical spirit of popular indigenous President Benito Juárez of the 1880s. But the military dictators of the 1920s were a more savage lot than Juarez."[23] Fox goes on to recount how priests were killed for trying to perform the sacraments, altars were desecrated by soldiers and freedom of religion outlawed by generals.[23]

Demographics

As many students of Latin American religion have pointed out, there is a substantial difference between describing oneself as religious or culturally religious and practicing one's faith literally. In the case of Mexico the decline of the church's religious influence is specially mirrored by the decline of church attendance among its citizens. Church attendance itself is a complex, multi-layered phenomenon that is subject to political and socio-economic factors. From 1940 to 1960 about 70% of Mexican Catholics attended church weekly while in 1982 only 54 percent partook of Mass once a week or more, and 21 percent claimed monthly attendance. Recent surveys have shown that only around 3% of Catholics attend church daily; however, 47% percent of them attend church services weekly [24] and, according to INEGI, the number of atheists grows annually by 5.2%, while the number of Catholics grows by 1.7%.[25][26]

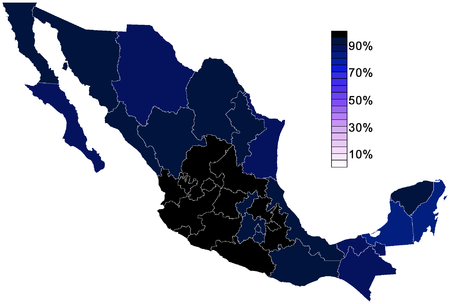

Irreligion by state

| Rank | Federal Entity | % Irreligious | Irreligious Population(2010) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13% | 177,331 | |

| 2 | 12% | 580,690 | |

| 3 | 12% | 95,035 | |

| 4 | 10% | 315,144 | |

| 5 | 9% | 212,222 | |

| 6 | 7% | 253,972 | |

| 7 | 7% | 194,619 | |

| 8 | 7% | 219,940 | |

| 9 | 7% | 174,281 | |

| 10 | 6% | 495,641 | |

| 11 | 6% | 108,563 | |

| 12 | 6% | 40,034 | |

| 13 | 6% | 151,311 | |

| 14 | 5% | 484,083 | |

| - | 5% | 5,262,546 | |

| 15 | 5% | 93,358 | |

| 16 | 4% | 169,566 | |

| 17 | 4% | 192,259 | |

| 18 | 4% | 58,089 | |

| 19 | 3% | 37,005 | |

| 20 | 3% | 486,795 | |

| 21 | 3% | 20,708 | |

| 22 | 3% | 100,246 | |

| 23 | 2% | 62,953 | |

| 24 | 2% | 58,469 | |

| 25 | 2% | 38,047 | |

| 26 | 2% | 21,235 | |

| 27 | 2% | 83,297 | |

| 28 | 2% | 104,271 | |

| 29 | 2% | 124,345 | |

| 30 | 1% | 76,052 | |

| 31 | 1% | 14,928 | |

| 32 | 1% | 18,057 |

Mexican atheists

- Guillermo Arriaga,[27] screenwriter and novelist

- Emmanuel Panizzo, filmmaker and philanthropist

- Hector Avalos, religion researcher

- Narciso Bassols, co-founded the Popular Party

- Luis Buñuel, Spanish-Mexican filmmaker

- Plutarco Elías Calles, president (1924–1928)

- Venustiano Carranza, President

- Leonora Carrington, artist

- Ricardo Flores Magón, anarchist revolutionary activist from the early 20th century

- Carlos Frenk,[28] cosmologist

- Tomás Garrido Canabal, politician

- Frida Kahlo, painter

- Guillermo Kahlo[29][30]

- Manuel de Landa, philosopher and artist

- Germán List Arzubide, poet and revolutionary

- Carlos A. Madrazo, politician

- Subcomandante Marcos,[31][32] activist

- Juan O'Gorman,[33] artist

- Ignacio Ramírez, "El Nigromante" also known as the Voltaire of Mexico

- Rius, cartoonist and highly critical of the Catholic Church

- Diego Rivera, muralist and Marxist

- Guillermo del Toro, filmmaker, author and actor

- Remedios Varo, Spanish-Mexican surrealist artist

- Alvaro Obregon, President

- Fernando Vallejo,[34] Colombian-Mexican writer

- Jorge Volpi, author

See also

References

- ^ a b Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States (1824) Archived 2012-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Article 130 of Constitution Archived 2007-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mexico". International Religious Report. U.S. Department of State. 2003. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Catholic News Agency Rise of atheism in Mexico

- ^ Aciprensa - Mexico still Catholic... but atheism is on the rise

- ^ http://www.jornada.unam.mx/ultimas/2013/12/02/el-90-de-los-mexicanos-cree-en-dios-encuesta-8448.html

- ^ Candidate Vicente Fox contributed to that perception with a letter (May 2000) to the religious authorities of the Protestant and Catholic churches, in which he made ten promises, ranging from defending the right-to-life, from the moment of conception until natural death (condemnation of abortion and euthanasia) to granting access to the mass communications media to religious organizations. Fox's promises proved expedient, because no political party held a majority in the Mexican Congress, elected on 6 July 2000. The Ten Promises appeared to be proof of an undemocratic the alliance between Protestant and Catholic religious authorities and presidential candidate Vicente Fox. Laura Randall (2006) Page 433

- ^ "Mexico - Religious Freedom Report 1999". Archived from the original on 2010-10-10. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ David Marshall Brooks, The Necessity of Atheism, Plain Label Books, 1933, ISBN 1-60303-138-3 p. 154

- ^ Maier, Hans and Jodi Bruhn Totalitarianism and Political Religions, pp. 109 2004 Routledge

- ^ Ehler, Sidney Z. Church and State Through the Centuries p. 579-580, (1967 Biblo & Tannen Publishers) ISBN 0-8196-0189-6

- ^ Needler, Martin C. Mexican Politics: The Containment of Conflict p. 50, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995

- ^ John Lear (2001). Workers, neighbors, and citizens: the revolution in Mexico City. U of Nebraska Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-8032-7997-1.

huerta high clergy.

- ^ Ignacio C. Enríques (1915). The religious question in Mexico, number 7. I.C. Enriquez. p. 10.

- ^ Robert P. Millon (1995). Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary. International Publishers Co. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7178-0710-9.

- ^ Carlo de Fornaro; John Farley (1916). What the Catholic Church Has Done to Mexico. Latin-American News Association. pp. 13–14.

urrutia .

- ^ Peter Gran (1996). Beyond Eurocentrism: a new view of modern world history. Syracuse University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8156-2692-3.

- ^ Laura Randall, Changing structure of Mexico: political, social, and economic prospects, (M.E. Sharpe, 2006) ISBN 0-7656-1404-9 Page 435

- ^ a b Fox, Vicente and Rob Allyn Revolution of Hope p. 17, Viking, 2007

- ^ [1]

- ^ Aciprensa

- ^ Catholic News Agency

- ^ "I don't believe in god, but I believe in destiny." "Our working relationship involves a lot of dialogue...we have very different viewpoints on certain things, like Alejandro's Catholicism and the fact that I'm an atheist." Filter Magazine

- ^ Sense about science[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Guillermo Kahlo was an educated, atheist, German-Jewish immigrant, who had come to Mexico as a young man and become an accomplished photographer, specializing in architectural photography". Samuel Brunk, Ben Fallaw, Heroes & hero cults in Latin America, (University of Texas Press, 2006), ISBN 0-292-71437-8 Page 174

- ^ "Her father Guillermo, from whom Frida inherited her creativity, was an atheist". Patrick Marnham, Diego Rivera Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera, (University of California Press, 2000), ISBN 0-520-22408-6 Page 220 [2]

- ^ "Marcos' revolutionary weddings were breaking the Church's monopoly on matrimonial services, and the Subcommander's presiding over them was perceived by the diocese as both an encroachment on Church prerogatives and as sacrilege. Marcos and the bishop were diametrically and vehemently opposed on certain issues, in particular birth control. Marcos believed whole-heartedly in it. The guerrillas were issued contraceptive devices at a clinic in Morelia which the government had helped found and fund. Nor was the encouragement and distribution of contraceptives restricted to the guerrillas themselves. Marcos believed that one of the major contributing factors to hardship and poverty was its overpopulation. Finally, according to one source at least, Marcos was becoming increasingly intolerant regarding questions of faith, even going so far as to preach atheism" Nick Henck, Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask, (Duke University Press, 2007) ISBN 0-8223-3995-1 Page 119

- ^ The War Against Oblivion : The Zapatista Chronicles 1994–2000

- ^ "Hasta ahora no profeso religión ni tengo razón para profesarla puesto que no creo en ninguna forma teológica". Juan O'Gorman, Autobiografía, (UNAM, 2007) ISBN 970-32-3555-7 [3]

- ^ "God is an excuse, a foggy abstraction that everyone uses for his own benefit and moulds it to the extent of his convenience and interests". Fernando Vallejo during the ceremony of the Rómulo Gallegos Prize in Venezuela