Hanako and the Terror of Allegory

| Hanako and the Terror of Allegory | |

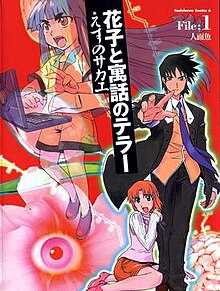

Cover of the first Japanese volume, published by Kadokawa Shoten on November 1, 2004 | |

| 花子と寓話のテラー (Hanako to Gūwa no Terā) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Sakae Esuno |

| Published by | Kadokawa Shoten |

| English publisher | |

| Magazine | Monthly Shōnen Ace |

| Demographic | Shōnen |

| Original run | April 26, 2004 – September 26, 2005 |

| Volumes | 4 |

Hanako and the Terror of Allegory (Japanese: 花子と寓話のテラー, Hepburn: Hanako to Gūwa no Terā) is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Sakae Esuno. It was serialized in the publisher Kadokawa Shoten's magazine Monthly Shōnen Ace from April 2004 to September 2005. The series individual chapters were compiled into four collected volumes and published from November 2004 to October 2005 by Kadokawa Shoten. It was later licensed in Northern America by Tokyopop for an English-language publication, which was released from March 2010 to April 2011. It has been republished by Kadokawa Shoten in 2011, and Viz Media released it in digital format in English.

The series tells the story of Daisuke Aso, a private detective who investigates paranormal cases involving Japanese urban legends that come to exist because of people's belief. Manga critics considered this concept interesting, although most of them did not find the series to be as unsettling as a horror series could be. Some argued it was more comedic than horrific, and its pacing was mostly criticized. Its art was met with divergent opinions, but the overall consensus is that while human characters are not well drawn, Esuno's monsters are very well done and horrifying.

Plot

Daisuke Aso (亜想 大介, Asō Daisuke) is a former police officer who is known as the allegory detective because he investigates allegories—urban legends that manifest physically and possess people who believe in them. Daisuke himself is possessed by two. The first is the belief that he will die if he hiccups more than 100 times in a row. When an allegory is closer, Daisuke hiccups, so it is his way to detect an allegory but in every case he runs the risk of dying of the hiccups. The second is Hanako (花子), a girl who in the legend haunts girls' school restrooms but now helps Daisuke to run his agency. She provides technical support by creating the "anti-allegory program" that can "de-visualize" the allegories, revealing their real form to its believers. Daisuke and Hanako are also accompanied by the human girl Kanae Hiranuma (平沼 カナエ, Hiranuma Kanae), who works with them since they helped to solve her allegory problem and she had no money to pay for it.

Publication

Written and illustrated by Sakae Esuno, the chapters of Hanako and the Terror of Allegory appeared as serial in the monthly manga magazine Shōnen Ace from April 26, 2004 to September 26, 2005.[3][4][5] Kadokawa Shoten collected its 19 chapters into four tankōbon volumes, and published them from November 1, 2004, to October 26, 2005.[6][7] Later, on September 26, 2011, Kadokawa started to re-release the series in a kanzenban edition, which spawned three volumes, with the last one being published on November 26, 2011.[8][9][10]

An English translation was done by Tokyopop that published the four volumes between March 9, 2010, and April 26, 2011.[11][12] As Tokyopop closed its North American publishing division in May 2011, its rights returned to Kadokawa Shoten.[13] In October 2015, Viz Media relicensed it and published the first three volumes in digital format from October 27 to December 22.[14][15][16] Hanako and the Terror of Allegory has also been translated into Chinese by Kadokawa Hong Kong,[17] and in French by Casterman.[18]

Volume list

| No. | Original release date | Original ISBN | English release date | English ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | November 1, 2004[6] | 4-04-713678-6 | March 9, 2010[11] | 978-1-4278-1608-5 |

| Daisuke Aso, a paranormal detective, is requested to solve three different cases involving urban legends. In the first, a girl known as Kanae Hiranuma says there is a man under his bed who will kill her if she sleeps. When he saves her with the help of his assistant Hanako, Kanae decides to help him. In the second, a girl takes the form of kuchisake-onna because she thinks her boyfriend does not consider her to be beautiful. With the detectives' help, the boy reveals his true love, making the girl return to her human form. In the last, a school bus falls in a lake; out of 40 students, only a survivor is found and all the other students became Fishmen—monsters with fish face and human body. As Daisuke kills all the Fishmen, he discovers the survivor was bullied and caused the accident in an attempt to kill himself and the bullies. The guilty he felt for causing the death of his girlfriend and to see his classmates being eaten by fish gave life to the Fishmen. | ||||

| 2 | January 26, 2005[19] | 4-04-713698-0 | August 13, 2010[20] | 978-1-4278-1609-2 |

| Four more cases appear to Daisuke, Hanako, and Kanae. In the first, Kanae is possessed by a wish-granting demon to whom she asks to be an idol. Kanae keeps wishing more things to distract the demon who ultimately kills himself because he is fed up with Kanae's desires. In the second, several girls have been shoved to death into the train railway. Hanako deduces the responsible for the deaths is the teke teke—a vengeful spirit of a girl who was cut in half by a train. In the end, they discover it is a suicide circle led by a terminally ill girl. In the third, a girl is paralyzed after her optical nerve is pulled out by a friend while she was piercing her ear. By entering her mind, Daisuke finds out it happened because she constantly witnessed her parents' fights and then wanted to shut off from reality. In the last, Daisuke starts to investigate a case involving the game kokkuri-san, while Hanako reveals to Kanae that Daisuke is half-allegory. While fighting the demon Kokkuri, Daisuke fully becomes an allegory after he almost dies. | ||||

| 3 | June 25, 2005[21] | 4-04-713733-2 | December 28, 2010[22] | 978-1-4278-1610-8 |

| Hanako explains Daisuke himself became an urban legend on the Internet and thus turned into an allegory. Daisuke's feelings for Kanae and her action to stop him makes Daisuke return to his human form. By destructing Kokkuri's ritual items, Hanako weakens the demon who is defeated by Daisuke. After this, the trio deal with three more cases. In the first, a man recluded himself for 15 years because he was dumped by a girl during school, giving life to the "woman in the gap". He takes his mother as a hostage and requests to see the girl only to discover she is fat, causing the allegory to disappear. In the second, they catch a serial killer who attacks girls' bathroom asking if they want red or blue paper. After that, Daisuke explains he is overzealous of Kanae because Mafuyu Tachibane, the woman he liked, died during an investigation. He closes the agency and separates from Hanako and Kanae, to whom a woman calling herself "Mafuyu Tachibane" appears. Two weeks later, Kanae returns home, where she is attacked by the doll Mary allegory. Hired by Kanae's grandfather and disguised, Daisuke and Hanako fight the doll, discovering the allegory appeared because Kanae threw away a doll that represented her vanishing twin, Nozomi. Kanae's body is possessed by Nozomi and attacks Daisuke. | ||||

| 4 | October 26, 2005[7] | 4-04-713756-1 | April 26, 2011[12] | 978-1-4278-1611-5 |

| Severely wounded, Daisuke transforms into an allegory but wanting not to hurt Kanae he apparently dies. Seeing this scene, Kanae takes control over her body and stabs herself to destroy Mary. After that, Kanae wakes up in a hospital, where she and Daisuke kiss each other. Then, the series go on a flashback about Daisuke's childhood: after his parents' divorce and the death of his father, Daisuke started to avoid interacting with people. Because of this, he was hospitalized and met a girl named Haruno Hanako, to whom he fell in love. Some time later Hanako dies, but she returns as the Hanako of the Toilet because she once said it and he believed on it. Back to the present, Mafuyu appears to Daisuke, Hanako, and Kanae and says she is the writer of a novel about their story. She apparently kills Hanako and Daisuke, claiming that this whole time Daisuke was dead and only existed because her novel became an urban legend. In fact, Daisuke read her novel as a child and was inspired by it to become a detective. But his story is now independent as he defeats Mafuyu and can live with Kanae and Hanako because they believe on it. | ||||

Reception

Most reviewers found its premise to be interesting, but there was no consensus on Esuno's ability to explore it properly. While Ash Brown of Experiments in Manga concluded "Esuno does some interesting things with it",[23] Shaenon Garrity wrote for About.com that the concept "is intriguing, but it's been done better—with creepier creatures, more atmospheric artwork, and cleverer twists on the basic premise—in manga like Eiji Otsuka's and Housui Yamazaki's Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service and CLAMP's xxxHolic."[24] Thomas Zoth of Mania considered that the first volume "fails to take full advantage of its potential" because of its episodic nature and lack of characters development.[25] In a review of the whole series, Richard Eisenbeis of Kotaku dubbed it "great fun" and said it "gets a lot of mileage out of its premise", praising how it interchanges between horror, action, comedy and romance and how in "each case you learn about a different Japanese urban legend and get hints about the deeper motivations and personal histories of each of the three main characters."[26] Both Carlo Santos of Anime News Network and Chris Zimmerman of Comic Book Bin also praised its mix of action and horror,[1][2] and Santos called it "the perfect horror-suspense blend".[27] Lori Henderson of Manga Xanadu said "it's the human elements of the stories, and their resolutions that [she] found to be the most interesting".[28] Oliver Ho of PopMatters considered it is full of aspects that were worth "a ponderous and academic exercise", saying that the series "seems to be a meditation ... on the relationship between storytelling and psychology."[29] He compared the fact that in the manga "characters must confront personal demons and fears in order to overcome evil spirits" to an affirmation by Bruno Bettelheim's on The Uses of Enchantment, where he writes that "a myth, like a fairy tale, may express an inner conflict in symbolic form and suggest how it may be solved."[29]

Overall, characters attracted criticism like those by Sean Gaffney of A Case Suitable for Treatment, who affirmed they are "rather colorless".[30] Kanae's role in the first volume was especially criticized by Garrity, who said her reasoning to become Daisuke's assistant is "more or less random".[24] Danica Davidson for Graphic Novel Reporter and Henderson also viewed negatively that Kanae's role was to be someone for Daisuke to rescue.[28][31] Bill Sherman of Blogcritics was more positive, saying in a volume two review that the main trio "remain appealing enough ... to get most readers wanting to find out what happens in the next book".[32] Although Snow Wildsmith of ICv2 dubbed the characters "forgettable", she appreciated the first volume because it shows that Daisuke has "a potentially interesting backstory."[33] Henderson also praised some of his backstory revelations,[28] while Zoth commented the mention of his special power in the first volume was a positive indication "that there is more depth to the world and characters than Esuno has thus far revealed."[25] Indeed, when this power was revealed, Santos affirmed "the most remarkable thing about Hanako that it still has the capacity to surprise",[27] and Zimmerman stated it was a "page turner" that "show[ed] exactly what Esuno is capable of when given the opportunity to explore his imagination."[34]

The series' horror was mostly criticized; Henderson asserted "it isn't really a horror title ... It's more of the psychological horror",[28] while Wildsmith considered the stories not "scary enough to make this collection horror", nor "thought provoking enough to make it a psychological thriller".[33] Sherman said it "isn't as unsettling as it could be: there are terrors, after all, which reflect the characters' primal fears, yet Esuno doesn't delve as deeply into 'em as he could".[35] Most reviewers agreed it was not that scary, but at least featured "creepy" and "spooky" moments.[24][25][31] Santos felt that it "would probably be a lot more horrifying ... if it didn't keep trying to be cute and funny with the characters", especially criticizing Hanako's role who "make[s] annoying quips that derail the creepy mood of the series".[1] Zack Davisson of Japan Reviewed remarked that when it "is playing with straight horror, it really shines" so the second and third volumes were considered an improvement over the first as they relied less on "cheap gags" and "panty-gags" and "deliver[ed] some actual horror".[36][37] Ho also said it has "an incredibly goofy sense of humour",[29] and while Garrity concluded that "promising blend of comedy and horror", the manga "doesn't quite work as comedy or horror",[24] some reviewers appreciated this humor and horror mix. Ed Sizemore of Comics Worth Reading affirmed it is a good reading for those who "like light horror with sense of humor",[38] and Henderson said it is "a light read with just a touch of the shiver factor".[28]

Esuno's art and its adequacy to a horror series received very discrepant opinions. Garrity commented the art is not "horrific" and that "most of the art is flat and generic, with vaguely cute big-eyed characters, bland backgrounds and a paucity of detail".[24] However, "horrific" was precisely the word used by Gaffney to describe it,[30] and Davisson wrote he has not "seen anyone draw horror as well as Esuno".[37] Zimmerman affirmed it is "downright creep at times",[2] and Sherman found "some effective visuals" like for the kuchisake-onna.[35] Scott Green of Ain't It Cool News, who said Esuno "isn't great at horror", praised the same scene and pondered that large-scale panels like those "manage [to provide] some creepy spectacles".[39] More consensual was that Esuno's monsters were better drawn his human characters. For example, Zoth praised backgrounds and monsters but called human designs "generic and unmemorable" and that "looks to be a half-finished state."[25] Henderson said, "It's fairly average in the portrayal of the humans, but the monsters are ... creepy and sometimes downright disturbing".[28] Santos commended Esuno's "striking supernatural imagery" as exemplified by how "classic creatures ... take on new levels of terrifying". He also praised its "straightforward paneling [that] brings the story to the forefront and minimizes distractions", but he said "some of the character designs look like the work of a rookie".[1][27] Zimmerman asserted that "though not quite as polished as fans have come to expect, [it] is fitting with his otherworldy designs and outlandish characters."[2] More negative was Wildsmith who called the art "ordinary: cute character types clash with uninspired horror images".[33] More positive was Sizemore, saying mood and emotions are well conveyed, and monsters are well crafted.[38]

Another aspect cited as a drawback to its horror was its pacing and the third story was especially criticized. Green said it "frequently suffers when the reader engages it" and that the twists in the first volume "are obvious or aggravating", considering the Human-Fish story "trampl[es] ground that will be very problematic for some audiences".[39] Grant Goodman of Pop Culture Shock criticized this story because of Esuno's treatment of rape, saying the girl saving her rapist vindicates his abuse.[40] Zoth considered the Human-Fish story "a complete misfire" and its twists "completely ridiculous".[25] Similarly, Santos and Zimmerman felt it was "convoluted", while considered the first chapter was "rushed", attributing it to Esuno's lack of pacing.[1][2] Nonetheless, both Santos and Zimmerman were mixed regarding the pacing. Although stated it was "so frequently sloppy in its execution", Santos praised it because "the deadpan, Twilight Zone-esque introductions to each chapter set the perfect tone, and the tension builds up at just the right pace—you know when those shocking moments are going to hit, but it doesn't make them any less terrifying when they happen".[1] Zimmerman commented that "if the series has one weakness, it would have to be its pacing", but "still, horror fans will find much to like about the series" as "the stories will have readers guessing the whole way through".[2] On the other hand, Henderson said the second and the third stories had "a nice twist",[28] and Gaffney affirmed "the pacing is excellent", commending the "balance between cute innocent victims, poorly communicating boyfriends, and complete jerkass monsters."[30]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Santos, Carlo (March 16, 2010). "Sebastian the Combat Butler". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 7, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Zimmerman, Chris (March 19, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory volume 1". Comic Book Bin. Toon Doctor. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; October 4, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ 少年エース2004年5月号 (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on April 1, 2004. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Esuno, Sakae (October 26, 2005). 花子と寓話のテラー 4 [Hanako and the Terror of Allegory 4] (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. p. 240.

- ^ 少年エース2005年11月号 (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on September 26, 2005. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" 花子と寓話のテラー (1) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on March 10, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Archived copy" 花子と寓話のテラー (4) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ 完全版 花子と寓話のテラー (1) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ 完全版 花子と寓話のテラー (2) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on October 31, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ 完全版 花子と寓話のテラー (3) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on December 30, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 1". Tokyopop. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 7, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ a b Manry, Gia (April 26, 2011). "North American Anime, Manga Releases: April 24–30". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 29, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ Manry, Gia (May 24, 2011). "Tokyopop: Japanese Manga Licenses to Revert to Owners". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; July 29, 2011 suggested (help) - ^ "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory, Volume 1". Viz Media. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory, Volume 2". Viz Media. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory, Volume 3". Viz Media. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ "完全版 花子和寓言敘事者 (3) (完)" (in Chinese). Kadokawa Hong Kong. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Naumann, Steve (April 6, 2010). "Hanako et autres légendes urbaines • Vol.1". Animeland (in French). Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" 花子と寓話のテラー (2) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on May 7, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 2". Tokyopop. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 6, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ "Archived copy" 花子と寓話のテラー (3) (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Manry, Gia (December 28, 2010). "North American Anime, Manga Releases: Dec. 26-Jan. 1". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; December 29, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ Brown, Ash (June 27, 2011). "My Week in Manga: June 20-June 26, 2011". Experiments in Manga. Manga Bookshelf. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Garrity, Shaenon (2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 1 & 2". About.com. IAC. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; October 17, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d e Zoth, Thomas (March 23, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Vol. #01". Mania. Demand Media. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; April 13, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ Eisenbeis, Richard (September 14, 2015). "A Manga About Urban Horror Stories Become Real". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c Santos, Carlo (August 17, 2010). "Magic Mushi Rooms". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; September 19, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Henderson, Lori (October 20, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 1". Manga Xanadu. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 25, 2012 suggested (help) - ^ a b c Ho, Oliver (April 6, 2010). "Four-Eyed Stranger #7: Myths to Die By". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c Gaffney, Sean (March 21, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 1". A Case Suitable for Treatment. Manga Bookshelf. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Davidson, Danica (March 2, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory". Graphic Novel Reporter. The Book Report. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; September 21, 2015 suggested (help) - ^ Sherman, Bill (April 26, 2011). "Manga Review: Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume Two by Sakae Esuno". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Hearst. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016 – via Blogcritcs.org.

{{cite web}}: External link in|via= - ^ a b c Wildsmith, Snow (March 11, 2010). "Review of 'Hanako and the Terror of Allegory' Vol. 1". ICv2. GCO. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; March 4, 2016 suggested (help) - ^ Zimmerman, Chris (August 26, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume 2". Comic Book Bin. Toon Doctor. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; August 27, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ a b Sherman, Bill (February 21, 2010). "Manga Review: Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume One by Sakae Esuno". Blogcritics. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Davisson, Zack (August 2, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory Volume Two". Japan Reviewed. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b Davisson, Zack (June 30, 2011). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory, Vol. 3". Japan Reviewed. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b Sizemore, Ed (September 14, 2010). "Tokyopop Chibis: Qwaser of Stigmata, Witch of Artemis, Alice in the Country of Hearts, more". Comics Worth Reading. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; November 21, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ a b Green, Scott (October 31, 2010). "Celebrating the Holiday With Horror Reviews". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; November 3, 2010 suggested (help) - ^ Goodman, Grant (April 11, 2010). "Hanako and the Terror of Allegory, Vol. 1". Pop Culture Shock. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

External links

- Hanako and the Terror of Allegory (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia