Isoquinoline

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Isoquinoline[1] | |||

| Other names

Benzo[c]pyridine

2-benzazine | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.947 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C9H7N | |||

| Molar mass | 129.162 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless oily liquid; hygroscopic platelets when solid | ||

| Density | 1.099 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 26–28 °C (79–82 °F; 299–301 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 242 °C (468 °F; 515 K) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | pKBH+ = 5.14[2] | ||

| −83.9·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Isoquinoline is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound. It is a structural isomer of quinoline. Isoquinoline and quinoline are benzopyridines, which are composed of a benzene ring fused to a pyridine ring. In a broader sense, the term isoquinoline is used to make reference to isoquinoline derivatives. 1-Benzylisoquinoline is the structural backbone in naturally occurring alkaloids including papaverine. The isoquinoline ring in these natural compound derives from the aromatic amino acid tyrosine.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

Properties

Isoquinoline is a colorless hygroscopic liquid at temperatures above its melting point with a penetrating, unpleasant odor. Impure samples can appear brownish, as is typical for nitrogen heterocycles. It crystallizes in form of platelets that have a low solubility in water but dissolve well in ethanol, acetone, diethyl ether, carbon disulfide, and other common organic solvents. It is also soluble in dilute acids as the protonated derivative.

Being an analog of pyridine, isoquinoline is a weak base, with a pKa of 5.14.[2] It protonates to form salts upon treatment with strong acids, such as HCl. It forms adducts with Lewis acids, such as BF3.

Production

Isoquinoline was first isolated from coal tar in 1885 by Hoogewerf and van Dorp.[9] They isolated it by fractional crystallization of the acid sulfate. Weissgerber developed a more rapid route in 1914 by selective extraction of coal tar, exploiting the fact that isoquinoline is more basic than quinoline. Isoquinoline can then be isolated from the mixture by fractional crystallization of the acid sulfate.

Although isoquinoline derivatives can be synthesized by several methods, relatively few direct methods deliver the unsubstituted isoquinoline. The Pomeranz–Fritsch reaction provides an efficient method for the preparation of isoquinoline. This reaction uses a benzaldehyde and aminoacetoaldehyde diethyl acetal, which in an acid medium react to form isoquinoline.[10] Alternatively, benzylamine and a glyoxal acetal can be used, to produce the same result using the Schlittler-Müller modification.[11]

Several other methods are useful for the preparation of various isoquinoline derivatives.

In the Bischler–Napieralski reaction an β-phenylethylamine is acylated and cyclodehydrated by a Lewis acid, such as phosphoryl chloride or phosphorus pentoxide. The resulting 1-substituted 3,4-dihydroisoquinoline can then be dehydrogenated using palladium. The following Bischler–Napieralski reaction produces papaverine.

The Pictet–Gams reaction and the Pictet–Spengler reaction are both variations on the Bischler–Napieralski reaction. A Pictet–Gams reaction works similarly to the Bischler–Napieralski reaction; the only difference being that an additional hydroxy group in the reactant provides a site for dehydration under the same reaction conditions as the cyclization to give the isoquinoline rather than requiring a separate reaction to convert a dihydroisoquinoline intermediate.

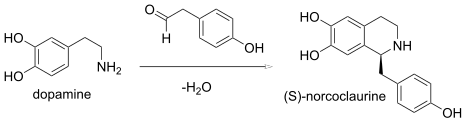

In a Pictet–Spengler reaction, a condensation of a β-phenylethylamine and an aldehyde forms an imine, which undergoes a cyclization to form a tetrahydroisoquinoline instead of the dihydroisoquinoline. In enzymology, the (S)-norcoclaurine synthase (EC 4.2.1.78) is an enzyme that catalyzes a biological Pictect-Spengler synthesis:

Intramolecular aza Wittig reactions also afford isoquinolines.

Applications of derivatives

Isoquinolines find many applications, including:

- anesthetics; dimethisoquin is one example (shown below).

- antihypertension agents, such as quinapril and debrisoquine (all derived from 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline).

- antiretroviral agents, such as saquinavir with an isoquinolyl functional group, (shown below).

- vasodilators, a well-known example, papaverine, shown below.

Bisbenzylisoquinolinium compounds are compounds similar in structure to tubocurarine. They have two isoquinolinium structures, linked by a carbon chain, containing two ester linkages.

In the human body

Parkinson's disease, a slowly progressing movement disorder, is thought to be caused by certain neurotoxins. A neurotoxin called MPTP (1[N]-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine), the precursor to MPP+, was found and linked to Parkinson's disease in the 1980s. The active neurotoxins destroy dopaminergic neurons, leading to parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. Several tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives have been found to have the same neurochemical properties as MPTP. These derivatives may act as precursors to active neurotoxins.[12]

Other uses

Isoquinolines are used in the manufacture of dyes, paints, insecticides and fungicides. It is also used as a solvent for the liquid–liquid extraction of resins and terpenes, and as a corrosion inhibitor.

See also

- Eletefine (1998), an isoquinoline alkaloid

- Naphthalene, an analog without the nitrogen atom

References

- ^ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 212. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b Brown, H.C., et al., in Baude, E.A. and Nachod, F.C., Determination of Organic Structures by Physical Methods, Academic Press, New York, 1955.

- ^ Gilchrist, T.L. (1997). Heterocyclic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Essex, UK: Addison Wesley Longman.

- ^ Harris, J.; Pope, W.J. "isoQuinoline and the isoQuinoline-Reds" Journal of the Chemical Society (1922) volume 121, pp. 1029–1033.

- ^ Katritsky, A.R.; Pozharskii, A.F. (2000). Handbook of Heterocyclic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

- ^ Katritsky, A.R.; Rees, C.W.; Scriven, E.F. (Eds.). (1996). Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry II: A Review of the Literature 1982–1995 (Vol. 5). Tarrytown, NY: Elsevier.

- ^ Nagatsu, T. "Isoquinoline neurotoxins in the brain and Parkinson's disease" Neuroscience Research (1997) volume 29, pp. 99–111.

- ^ O'Neil, Maryadele J. (Ed.). (2001). The Merck Index (13th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck.

- ^ S. Hoogewerf and W.A. van Dorp (1885) "Sur un isomére de la quinoléine" (On an isomer of quinoline), Recueil des Travaux Chemiques des Pays-Bas (Collection of Work in Chemistry in the Netherlands), vol.4, no. 4, pages 125–129. See also: S. Hoogewerf and W.A. van Dorp (1886) "Sur quelques dérivés de l'isoquinoléine" (On some derivatives of isoquinoline), Recueil des Travaux Chemiques des Pays-Bas, vol.5, no. 9, pages 305–312.

- ^ Li, J. J. (2014). "Pomeranz–Fritz reaction". Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Mechanisms and Synthetic Applications (5th ed.). Springer. pp. 490–491. ISBN 9783319039794.

- ^ Li, J. J. (2014). "Schlittler–Müller modification". Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Mechanisms and Synthetic Applications (5th ed.). Springer. p. 492. ISBN 9783319039794.

- ^ Niwa, Toshimitsu; Kajita, Mitsuharu; Nagatsu, Toshiharu (1998). "Isoquinoline Derivatives". Pharmacology of Endogenous Neurotoxins. pp. 3–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2000-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4612-7375-2.

External links

. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 758–759.