Tamandua

| Tamandua | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | Myrmecophagidae |

| Genus: | Tamandua Rafinesque 1815 |

| Type species | |

| Myrmecophaga tamandua[1] | |

| Species | |

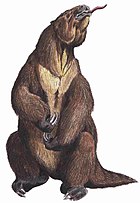

Tamandua is a genus of anteaters in the Myrmecophagidae family with two species: the southern tamandua (T. tetradactyla) and the northern tamandua (T. mexicana).[1] They live in forests and grasslands, are semiarboreal, and possess partially prehensile tails. They mainly eat ants and termites, but they occasionally eat bees, beetles, and insect larvae. In captivity, they will eat fruits and meat. They have no teeth and depend on their powerful gizzards to break down their food.

Taxonomy

The genus name is derived from the word tamãdu'á in Tupi[2][3] first recorded by Joseph of Anchieta in his Epistola quam plurimarum rerum naturalium quae S. Vicentii (nunc S. Pauli) provinciam incolunt sistens descriptionem (1560); ta- in tamãdu'á is deduced from taixi "ant" and the other half from mondé "to catch", mondá "thief" or monduár "hunter".[4]

Extant species

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

T. mexicana | Northern tamandua | from southeastern Mexico south throughout Central America, and in South America west of the Andes from northern Venezuela to northern Peru |

|

T. tetradactyla | Southern tamandua | from Venezuela and Trinidad to northern Argentina, southern Brazil and Uruguay. |

Description

Tamanduas have tapered heads with a long, tubular snout, small eyes, and protruding ears. Their tapered mouths house a tongue reaching upwards of 40 cm (16 in) in length. The tail is hairless and pink in color, marked with an irregular pattern of black blotches. The forefeet possess four clawed digits, the third digit bearing the largest claw, while the hind feet have five digits.[5]

Their fur is thick, bristly, yellowish-white to fawn in color, often with a broad black lateral band, covering nearly the whole of the side of their bodies. Northern tamanduas are marked with a black V on their backs and a "vest" over their torso; southern tamanduas vary in appearance across their range, from a vested pattern like northern tamandua, to only partially vested, to entirely light- or dark-colored.[6]

Behavior

Tamanduas are nocturnal, active at night and secreting away in hollow tree trunks and burrows abandoned by other animals during daylight hours. They can spend more than half of their time in the treetops, as much as 64%, where they forage for arboreal ants and termites. Tamanduas move rather awkwardly on the ground and are incapable of galloping like their relative, the giant anteater. Tamanduas walk on the sides of their clenched forefeet to avoid injuring their palms with their sharp claws.[5]

Tamanduas manufacture a potent musk in their anal glands that they use for marking territory. They smear the strong-smelling secretions on rocks, trees, fallen logs, and other prominent landmarks to announce their presence to other tamanduas.[7]

When threatened while in the trees, the tamandua will firmly grasp the branch with its hind limbs and tail and rear up to confront its attacker with slashing motions of its large, curved claws. When on the ground, it will protect its vulnerable hindquarters by backing against a tree or a rock and lashing out with its forearms.[8]

The tamandua's small eyes afford limited vision. Instead of relying on their sense of sight, they primarily utilize their senses of smell and hearing to locate their insect prey. They use their sharp claws and powerful forearms to tear open the nest of a colony of termites and employ their elongated tongues, coated with sticky saliva, to extract the insects.[7]

Female tamanduas reach sexual maturity at one year old and during their gestation period, which is around 160 days, typically have a single offspring. After being born, a tamandua pup rides on its mother's back and is left on a branch while its mother forages.[8]

Conservation

The IUCN Red List considers both as species of concern. They are currently fairly common, yet face various threats. In Ecuador, tamanduas are killed as a precaution due to the erroneous belief that they attack domestic dogs. Elsewhere, they are hunted for meat or captured for the pet trade.[8][9] They are also taken for the thick tendons in their tails, which are made into cordage.[5]

Relationship with humans

The tamandua is frequently kept as an exotic pet.[8][9] Tamanduas are also used occasionally by Amazonian Native Tribes as a form of biological pest control, utilizing them to rid their dwellings of termites and ants.[5]

References

- ^ a b Gardner, A. (2005). "Family Myrmecophagidae". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "tamandúa". Los diccionarios y las enciclopedias sobre el Académico (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Ferreira, A. B. H. (1986). Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. p. 1644.

- ^ Papavero, Nelson; Teixeira, Dante Martins (2014). Zoonímia tupi nos escritos quinhentistas europeus (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Arquivos do NEHiLP. pp. 92, 257. ISBN 978-85-7506-230-2.

- ^ a b c d Gorog, Antonia. "Tamandua tetradactyla". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Harrold, Andria. "Tamandua mexicana". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b Kirlon, John. "Tamandua tetradactyla (Southern Tamandua or Lesser Anteater)" (PDF). University of the West Indies. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Ortega Reyes, J.; Tirira, D.G.; Arteaga, M.; Miranda, F. (2014). "Tamandua mexicana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21349A47442649. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21349A47442649.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b Miranda, F.; Fallabrino, A.; Arteaga, M.; Tirira, D.G.; Meritt, D.A.; Superina, M. (2014). "Tamandua tetradactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T21350A47442916. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T21350A47442916.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.