Perry Rhodan

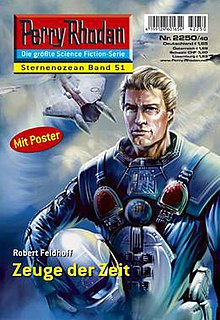

Perry Rhodan is the eponymous hero of a German science fiction novel series which has been published each week since 8 September 1961 in the 'Romanhefte' format (digest-sized booklets, usually containing 66 pages, the German equivalent of the now-defunct American pulp magazine) by Pabel-Moewig Verlag, a subsidiary of Bauer Media Group. As of February 2019, 3000 booklet novels of the original series plus 850 spinoff novels of the sister series Atlan plus over 400 paperbacks and 200 hardcovers have been published, totalling over 300,000 pages. Having sold approximately two billion copies (in novella format) worldwide alone, (including over one billion in Germany), it is the most successful science fiction book series ever written. The first billion of worldwide sales was celebrated in 1986.[1]

The first 126 novels (plus five novels of the spinoff series Atlan) were translated into English and published by Ace Books between 1969 and 1978, with the same translations used for the British edition published by Futura Publications which issued only 39 novels. When Ace cancelled its translation of the series, translator Wendayne Ackerman self-published the following 19 novels (under the business name 'Master Publications') and made them available by subscription only. Financial disputes with the German publishers led to the cancellation of the American translation in 1979.

An attempt to revive the series in English was made in 1997–1998 by Vector Publications of the US which published translations of four issues (1800–1803) from the current storyline being published in Germany at the time.

The series and its spin-offs have captured a substantial fraction of the original German science fiction output and exert influence on many German writers in the field.[citation needed] The series is told in an arc storyline structure. An arc—called a "cycle"[2]—would have anywhere from 25 to 100 issues devoted to it, similar subsequent cycles are referred to as a "grand-cycle".[3]

Matthias Rust, the then-19 year old aviator who landed his Cessna 172 aircraft on the Red Square in Moscow in 1987, has cited Perry Rhodan's adventures as his main inspiration to penetrate Soviet airspace.[4]

History

‘Perry Rhodan, der Erbe des Universums’ (Eng: ‘The Heir to the Universe’, though the American/British editions instead used the subtitle 'Peacelord of the Universe') was created by German science fiction authors K. H. Scheer and Walter Ernsting and launched in 1961 by German publishing house Arthur Moewig Verlag (now Pabel-Moewig Verlag). Originally planned as a 30 to 50 volume series, it has been published continuously every week since, reaching more than 2,950 issues as of March 2018. Written by an ever-changing team of authors, many of whom, however, remained with the series for decades or life, Perry Rhodan is issued in weekly novella-size installments in the traditional German Heftroman (pulp booklet) format. Unlike most German Heftromane Perry Rhodan consists not of unconnected novels but is a series with a continuous, increasingly complex plotline, with frequent back references to events. In addition to its original Heftroman form, the series now also appears in hardcovers, paperbacks, e-books, comics and audiobooks.

Over the decades there have also been comic strips, numerous collectibles, several encyclopedias, audio plays, inspired music, etc. The series has seen partial translations into several languages. It also spawned the 1967 movie Mission Stardust (aka …4 …3 …2 …1 …morte),[5] which is widely considered so terrible that many fans of the series pretend it never existed.[6][7][8]

Coinciding with the 50th-anniversary World Con, on 30 September 2011, a new series named Perry Rhodan Neo began publication, attracting new readers with a reboot of the story, starting in the year 2036 instead of 1971,[9] and a related but independent story-line.

Plot

The story line starts in 1971 with the first manned moon landing by U.S. Space Force Major Perry Rhodan and his crew, who discover a marooned extraterrestrial space ship from the (fictional) planet Arkon in the (real) M13 cluster.[10] Appropriating the Arkonide technology, they proceed to unify Terra and carve out a place for humanity in the galaxy and the cosmos. (The concepts for two of the technical accomplishments that enable them to do so—positronic brains and starship drives for near-instantaneous hyperspatial translation—are direct adoptions from Isaac Asimov's science fiction universe.)

As the series progresses, major characters, including the title character, are granted relative immortality.[11] It is relative in the sense that they are immune to age and disease, but could suffer a violent death. The story continues over the course of millennia, including flashbacks thousands and even millions of years into the past, and the scope widens to encompass other galaxies, extremely remote parts of space, parallel universes and weirder cosmic structures, time travel, paranormal powers, weird/cute/aggressive aliens and bodyless entities (some with sheer god-like powers).

Universe and multiverse

The universe in which the plot regularly takes place is called the Einstein Universe (and occasionally "Meekorah"). Its laws are mostly identical to those of our real universe. Newer theories about dark matter and dark energy are currently not used in the series, and sometimes the laws of nature follow old theories that have been disproven—to protect the plot.

This Einstein Universe is only one in a large ensemble of universes, each to a greater or lesser extent different from it (for example a universe in which time runs slower, an anti-matter universe, a shrinking universe). Additionally, each universe possesses a large ensemble of parallel timelines, which are usually unreachable from each other but may be accessed by special means—thereby itself creating many more parallel timelines.

The Einstein Universe is embedded in a high-dimensional manifold, called Hyperspace. This hyperspace consists of several subspaces, that are used by different technologies for faster-than-light travel. The exact traits of those higher dimensions are not thoroughly explained. The border of the universe is a dimension called the deep (once used for construction of the gigantic discworld "Deepland").

Psionic Web and Moralic Code

The Psionic Web crosses invisibly through the whole universe, constantly emitting "vital energy" and "psionic energy", guaranteeing normal (organic among others) life and the well-being of higher entities.

The Moralic Code crosses through all universes, and is linked to the Psionic Web. It is subdivided into the Cosmogenes, which are again subdivided into the Cosmonucleotids. (These names and associations to DNA were given by the cosmocrats, and should not be misunderstood as having an absolute ethical meaning.) The Cosmonucleotids determine reality and fate themselves for their respective parts of a given universe, via messengers.

Higher beings are trying to gain control of this possibility to rule reality itself. The Moralic Code itself was not installed by the higher beings, the higher powers by themselves have no clue why or by whom the Code was made.

Once the cosmocrats ordered Perry Rhodan to find the answers to the three ultimate questions; apparently they have known the answer to the first and second question but not to the third, which reads "Who initiated the LAW and what does it cause?". Perry Rhodan had the chance to receive the answer at the mountain of creation, but he refused, knowing that the answer would destroy his mind. It is known that the negative Superintelligence Koltoroc had received the answer to the last ultimate question, 69 million years BC at Negane Mountain, but it is not known if it made any use of that knowledge.

Onion-shell model

To all life, an evolutionary theory called the "onion-shell model" is employed. It states that there is a continuous evolution from lower life-forms (bacteria) to higher life-forms like intelligent life and finally bodyless entities. Upon invention, the onion-shell-model was used by the authors as if there were definite and discrete stages in cosmological evolution. However, later in the series, further life-forms, representing stages between the known shells, were introduced.

The main shells are:

- Life-less matter

- Bacteria

- Higher animals

- Intelligent species

- Intelligent species that have contacted other species

- Superintelligences (SI)

- Matter-fountains / Matter-sinks

- Cosmocrats / Chaotarchs (High Powers)

- Powers close to the "Horizon of the LAW", the essence of the Multiverse ("Thez", Volume 2874)

The superintelligences are the next step above normal minds. They are born, for example, when a species collectively gives up its bodies and unites their spirits. Those superintelligences claim a domain as theirs, consisting of up to several galaxies (the entity known as "ES ('IT')" has the Local Group as personal domain). The superintelligence nourishes mentally on the species in its domain, sometimes symbiotically (positive SI), sometimes parasitically (negative SI). Again, these attributes should not be treated as ethical description, although negative superintelligences are in general described as being more sinister.

The matter-fountains/matter-sinks are born, when a superintelligence fuses with all life and matter in its domain while shrinking. Little more is known, except that the process is gradual and that the resulting object doesn't have the intense gravitational pull it would have if the contraction produced a black hole.

The "high powers" were long known to be the highest known life-forms. They live in an unimaginable, distant dimension and have great powers in ruling over lower beings. However they are not omniscient and they are unable to directly interact with lower beings. To enter a regular universe, they have to put on a mortal shape, reducing their powers and sometimes their knowledge/memory. This is known as the transform-syndrome. Due to this, they rarely interact with lower beings and instead enlist individuals, organisations or entire species.

Conflict between the high powers

Among the high powers are two factions known as the cosmocrats and the chaotarchs. The cosmocrats want to transform all universes into a state of absolute order (a state of utmost entropy, usual symbol S), while the chaotarchs want to transform all universes into a state of absolute chaos (negative entropy). Accordingly, they are engulfed in a cataclysmic neverending war, stretching among almost all known universes. They are ruthlessly using, manipulating and dooming whole species for their actions. However, open warfare is just one tool among many in their epic conflict. In the previous cycle (2300–2499) the Milky Way galaxy was victim of a full-fledged military assault by the forces of chaos trying to establish a bastion of chaos, a negasphere, in the nearby galaxy Hangay.

Recently it was revealed to the protagonists that life itself has become a rival to the higher powers. It has spread uncontrollably among the universe and can be found in virtually every niche. The cosmocrats and chaotarchs both use life for its tendencies to create order and chaos alike. Its unplanned and unregulated cosmological actions and manipulations are a constant disturbance for the plans of the cosmocrats and the chaotarchs alike. The Pangalactic Statisticians (a neutral organization of observers) have stated that 21% of all cosmological manipulations are executed by cosmocrat-servants, 16% are executed by chaos-servants and 63% are executed by the vast uncontrollable life itself.[12]

To reduce the influence of life, the cosmocrats have stopped their programs that encourage the development of life and intelligence. Additionally, they have increased the hyper-impedance, drastically reducing the effectivity and durability of most forms of hyper-technology.[13]

Recently, at least one power developed higher than the cosmocrats and chaotarchs has been identified: Thez. It is said that it lives so close to the "Horizon of the LAW" that both cosmocrats and chaotarchs have problems to understand it.

Critical reaction

In the introduction to the first English-language edition of Perry Rhodan in 1969, Forrest J Ackerman said that "In Germany, all serious SF buffs claim to hate Perry Rhodan, but somebody (in unprecedented numbers) is certainly reading him."[14] Many American SF fans agreed with the first part of that statement, feeling the series was an embarrassment and too "juvenile". Tom Doherty, new head of Ace Books in the mid-to-late '70s, concurred and ended the series in the US, even though it was profitable.[15] This decision meant that by 1980, when the original German versions of Perry Rhodan were becoming "more sophisticated and less aimed at younger readers", the series was no longer available in English.[16]

Critic Robert Reginald described the series as the "ultimate soap opera of science fiction"[17] and standard "pulp science fiction, action stories with minimal characterization, awful dialog, but relatively complex plot development. The emphasis is always on man's expanding horizons, the wonder of science and space, the great destiny of the human race."[18]

The series' beginnings were often criticized for their description of an expansive mankind and frequent space battles; after William Voltz took over the position of storyline planner for the series in 1975 (a post he held until his death in 1984), the series developed a broader ethical scope and also evolved in terms of storytelling style.

But while many critics dismiss the series, many others praise it. There appears to be the conundrum that, especially in the US, the newer, more complex parts of the series have never been published, so critical review tends to be concentrated on the rather simple origins of the series. John O'Neill has called Perry Rhodan "one of the richest—if not the richest—Space Operas ever written."[19]

Publication

English translation

In the 1960s, Forrest J Ackerman organized the publication in the U.S. of an English translation of the series, with his wife Wendayne in charge of translation. Other translators on the series included Sig Wahrmann, Stuart J. Byrne, and Dwight Decker. Number 1, containing German issues 1 and 2, was published by Ace Books starting in 1969. Acting as Managing Editor, Ackerman soon incorporated elements reminiscent of the SF pulp magazines of his youth, such as short stories, serialized novels and a film review section. The series was a commercial success, eventually being published three times per month.[20]

Ace ended its regular run of Perry Rhodan in August 1977 with double issue #117/118. However this was followed by the publication of three "missing" stories (i.e. novellas from earlier in the series which had not been translated and left out of the series by editorial decision),[21] accompanied by three novellas from the Perry Rhodan spinoff series Atlan.

Ace concluded its run of translations with two further Atlan novels and a novel-length story, 'In the Center of the Galaxy [German: Im Zentrum der Galaxis] [22]' by Clark Darlton, which had appeared in German as issue 11 of the "Perry Rhodan Planet Novels [Planetenromane]" spin-off series.

When Ace cancelled its publication of the series in 1978, translator Wendayne Ackerman self-published the following 19 novels (numbered #119 – 137) under the business name Master Publications before this subscription-only edition was also cancelled in 1979. That was the end of an English version until the 1990s, when Vector Enterprises restarted an American version. This version lasted for four printed issues and one electronic issue—#1800 to #1804.

In 2006, Pabel-Moewig Verlag licensed FanPro to publish an English translation of the "Perry Rhodan: Lemuria" miniseries. Some material present in the German version, such as a history of generation spaceships in science fiction, was dropped from the American version. Only the first volume was released.

In 2015—16, Perry Rhodan Digital published English translations of the full six-volume Perry Rhodan: Lemuria story arc in ebook format, making these available via iTunes and other digital platforms.

In other countries

Translations of Perry Rhodan are currently available in Brazil (#1 to #536 and #650 to #847 as of August 2011), and also from 537 to 649; 1400 in before (at present, in December 2014), including the series Atlan, Planetary Novels and Perry Rhodan NEO (at present in the n. 28), all launched by the "Project Translation", Russia, China, Japan(#1 to #800 as of May 2011), France, the Czech Republic, and the Netherlands (#1 to #2000 as of September 2009). Apart from the US version, there were also editions in Canada, Great Britain (#1 to #39), Italy and Finland. However, the latter have been discontinued.

The first language into which Perry Rhodan was translated was Hebrew. In 1965, the first four episodes appeared in Tel Aviv in a pirated translation, and which for unknown reasons ceased before publication of the fifth (it was not because it was detected by the German publishers, who only heard about it many years later). The few surviving copies of this 1965 translation are highly valued by Israeli collectors.[23]

Structure

Cycles

The original series is divided into the following cycles and grand cycles:

- Note: Only the grandcycles The Great Cosmic Mystery and Thoregon have official names. The other grandcycles weren't planned as such. They were named by the readers in hindsight due to their shared themes.

|

|

|

American publication history

- Ace Books

- #1 to #5—Double issues. Each volume contains two episodes, but edited to be a single novel.

- #6 to #108—Single issues. "Maga-book" format, or the format of a magazine in the style of a book. Letter and film review in #6. Would later include short stories—old and new—and reprints of classic serialized novels such as Edison's Conquest of Mars by Garrett P. Serviss (reprinted as Pursuit to Mars). Of special note is a lost chapter of the H.G. Wells novel The Time Machine that was published in this manner.

- #109 to #118—double issues again, but each one set apart.

- Perry Rhodan Specials #1 to #5—Double issues. #1 to #3 are lost episodes published with an Atlan episode. #4 are two Atlan episodes and #5 (unnumbered) is a Planetenroman.

- Master Publications

- #119 to #136—Magazine size and format.

- #137—Book format. To fill out remaining subscription orders, the book format also printed Stuart J. Byrne's Star Man series. #137 was published with the first five episodes of Star Man in one volume. The remaining Star Man episodes were published as a separate volume.

- Vector Enterprises

- #1800 to #1803—Magazine format. #1800 is published in a manner similar to the German series. 1801 to 1803 are large-sized magazine format.

- #1804—Electronic format only.

- FanPro Games (American operation of German company FanPro)

- Lemuria #1 "The Star Ark"

Copies of the Ace books and the rarer magazine versions can be found in online auction sites such as eBay and fixed-price online stores like Amazon.com. Used bookstores often have some of the Ace books, but rarely the magazine versions[citation needed].

Cultural impact

In space

Dutch ESA astronaut André Kuipers was inspired to become an astronaut from an early age by the Perry Rhodan albums his grandmother bought for him (and that he eventually started buying himself from his allowance). When he finally went into space, on 18 April 2004, he brought his very first booklet along with him. It was number ten in the red series, Ruimteoorlog in de Wegasector ("Space War in the Vega Sector" or "Raumschlacht im Wega-Sektor").[24]

In music

Christopher Franke, former member of German electronica group Tangerine Dream and soundtrack composer for U.S. science-fiction TV series Babylon 5, released Perry Rhodan Pax Terra in 1996, composed of music inspired by the Perry Rhodan epic.

The German group The Psychedelic Avengers claim to be inspired by Perry Rhodan on their 2004 release And the Curse of the Universe. The group Sensus released a song "Perry Rhodan ... More Than A Million Lightyears From Home" in 1986 (and presented it at the Worldcon in Saarbrücken).

In science fiction fandom

Bubonicon, an annual science fiction convention in Albuquerque, New Mexico, US, adopted as its mascot Perry Rhodent, a rat wearing only one shoe (or boot). Perry's image is reinvented each year for the convention's program and T-shirts, often by the convention's Artist Guest of Honor.[citation needed]

George Lucas, the creator of the Star Wars franchise, mentioned that he read the American translation of Perry Rhodan in the late 1960s and early 1970s and considers the series to be an "inspiration, less strong than Flash Gordon, but it influenced the design of many starships of Star Wars".[25][26]

Selected writers

Past writers

Guest writers

See also

References

- ^ "Perry Rhodan 35th anniversary Press Release". Archived from the original on 30 April 2008.

- ^ "Teil 2 - Hintergründe" (in German). Archived from the original on 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Zyklen" (in German). Archived from the original on 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Kremlin Caper: Mathias Rust's Landing on Red Square". YouTube. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ ...4 ...3 ...2 ...1 ...morte (aka Mission Stardust) at IMDb

- ^ "Perry Rhodan: Mission Stardust". The Spinning Image. 30 May 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "Perry Rhodan – SOS from Space". BadMovies (in German). Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "FAQ Perry Rhodan: 11. Is there a Perry Rhodan movie?". Perry-Rhodan.us. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "Perry Rhodan about to reboot". The Trek BBS. 6 August 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "Unternehmen Stardust – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "Der Unsterbliche – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "Pangalaktische Statistiker – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "Hyperimpedanz – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Ackerman, Forrest J (1969). "Introducing Perry Rhodan and His Electric Personality". Perry Rhodan #1: Enterprise Stardust. Ace Publications. p. 6. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Mike Ashley; Michael Ashley (14 May 2007). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970-1980. Liverpool University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Deborah Painter (2010). Forry: The Life of Forrest J Ackerman. McFarland. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7864-5798-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ R. Reginald (1 November 1996). Xenograffiti: Essays on Fantastic Literature. Wildside Press LLC. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-8095-1900-2. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Neil Barron; Robert Reginald (November 2009). Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Review. Wildside Press LLC. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-89370-609-8. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ " O'Neill, John (1998). "The Return of Perry Rhodan". SF Site. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Forrest J Ackerman (1975). Editorial announcement in Perry Rhodan #69: The Bonds of Eternity. Ace Books, Inc.

- ^ Forrest J Ackerman (1977). Editorial announcement in Perry Rhodan #117/118: Savior of the Empire/The Shadows Attack. Ace Books, Inc. p. 7.

- ^ "Im Zentrum der Galaxis". Perrypedia.

- ^ "פרי רודאן -איש החלל הניצחי | המולטי יקום של אלי אשד". Notes.co.il. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "André Kuipers' diary – Part 2: Medical examination; six crowns / Delta Mission / Human Spaceflight / Our Activities / ESA". Esa.int. 16 February 2004. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Der deutsche Zukunftsroman 1918-1945: Gattungstypologie und ... - Dina Brandt - Google Books. Books.google.ch. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "Science-Fiction-Serie aus Rastatt soll verfilmt werden: Perry Rhodan fordert Darth Vader zum Duell - Seite 2 - Aus aller Welt - Panorama" (in German). Handelsblatt. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

External links

- Perry Rhodan Official Homepage (in German)

- Perry Rhodan Official Homepage (in English)

- Another Official Perry Rhodan Page (in English)

- Perry Rhodan Encyclopedia »Perrypedia« (in German)

- Perry Rhodan Encyclopedia »Perrypedia« (in English)

- Series summary

- Mission Stardust (aka …4…3…2…1…morte) at the Internet Movie Database

- Perry Rhodan series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Perry Rhodan - The Adventure, Computer Game site

- Technology of the Perry Rhodan Universe

- Cédric Beust's Issue Summaries

- Official French Homepage