Ba Maw

Ba Maw | |

|---|---|

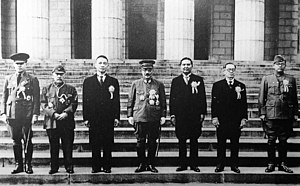

| File:Ba Maw, 1943.jpg Ba Maw having just been awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, March 1943 | |

| Head of State (Naingandaw Adipadi) | |

| In office 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| 1st Premier of British Crown Colony of Burma | |

| In office 1937–1939 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | U Pu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 February 1893 Maubin |

| Died | 29 May 1977 (aged 84) Rangoon |

| Spouse |

Khin Ma Ma Maw

(m. 1926; died 1967) |

| Relations | Ba Han (brother) |

| Children | 7 including: Banya Maw and Tinsa Maw |

| Parent(s) | Shwe Kye (father) Thein Tin (mother) |

| Alma mater | Rangoon College (B.A.) University of Calcutta (M.A.) University of Cambridge (LL.M.) University of Bordeaux (Ph.D.) |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

Ba Maw (Template:Lang-my, pronounced [ba̰ mɔ̀]; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese barrister and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. He was 1st Burma Premier (1937–1939) and head of State of Burma (Myanmar) from 1943 to 1945.[1]

Early life and education

Ba Maw was born in Maubin. Ba Maw came from a distinguished family of mixed Mon-Burman parentage.[2][3] His father, Shwe Kye was an ethnic Mon from Amherst (now Kyaikkhami) and well-versed in French and English languages. Thus Shwe Kye served as a royal diplomat who accompanied Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung in the Burmese diplomatic missions to Europe in the 1870s, and worked as an assistant tutor to Royal tutor Dr. Mark at the last royal palace of the last Burmese monarchy.[4] Ba Maw's elder brother, Professor Dr Ba Han (1890–1969), was a lawyer as well as a lexicographer and legal scholar, and served as Attorney General of Burma from 1957– 1958.

After an education at Rangoon College, Ba Maw obtained MA degree from the University of Calcutta in 1917. Then he was educated at Cambridge University in England and received a law degree from Gray's Inn where he was called to the bar in 1923.[5][6] He went on to obtain a doctoral degree from the University of Bordeaux, France. Ba Maw wrote his doctoral thesis in the French language on aspects of Buddhism in Burma.

Academic career

After graduating from Rangoon College in 1913, Ba Maw began working as a teacher at Rangoon Government High School and later at ABM school. In 1917, he got an MA from the University of Calcutta, and became the first English lecturer at Rangoon University where he worked for the next four years.[citation needed]

Lawyer career

From the 1920s onwards, Ba Maw practiced law and dabbled in colonial-era Burmese politics. He achieved prominence in 1931 when he defended the rebel leader, Saya San. San had started a tax revolt in Burma in December 1930 which quickly grew into a more widespread rebellion against British rule. San was captured, tried, convicted and hanged. Ba Maw was among the top lawyers who defended San. One of the presiding judges that tried San was another Burmese lawyer Ba U.[citation needed]

Politics

Starting from the early 1930s Ba Maw became an outspoken advocate for Burmese self-rule. He at first opposed Burma's colonial separation from British India but later supported it. After a period as education and public health minister, he served as the first Prime Minister or Premier of Burma (during the British colonial period) from 1937 to February 1939, after first being elected as a member of the Poor Man's Party to the Legislature. He opposed the participation of Great Britain, and by extension Burma, in World War II. He resigned from the Legislature and was arrested for sedition on 6 August 1940. Ba Maw spent over a year in jail as a political prisoner. He was incarcerated for most of the time in Mogok jail, situated in a hill station in eastern Burma.[citation needed]

During the early stages of World War II, from January to May 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army quickly overran Burma, and after the capture of Rangoon, freed Ba Maw from prison. During the Japanese occupation of Burma, Ba Maw was asked by the Japanese to head a provisional civilian administration to manage day-to-day administrative activities subordinate to the Japanese military administration. This Burmese Executive Administration was established on 1 August 1942.[citation needed]

As the war situation gradually turned against the Japanese, the Japanese government advanced its previously vague promise to grant Burma independence after the end of the war.[7] The Japanese felt that this would give the Burmese a real stake in an Axis victory in the Second World War, creating resistance against possible re-colonization by the western powers, and increased military and economic support from Burma for the Japanese war effort. A Burma Independence Preparatory Committee chaired by Ba Maw was formed 8 May 1943 and the nominally independent State of Burma was proclaimed on 1 August 1943 with Ba Maw as "Naingandaw Adipadi" (head of state) as well as prime minister. The new state quickly declared war on the United Kingdom and the United States, and concluded a Treaty of Alliance with the Empire of Japan. Ba Maw attended the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo in November 1943, where he made a speech speaking of how it was the call of Asiatic blood that drew them together into a new era of unity and peace.[8] However, the new state failed to secure popular support or diplomatic recognition due to the continued presence and activities of the Imperial Japanese Army, and after their collaborationist allies, the Burma National Army defected to the Allies side, the government collapsed.[citation needed]

Ba Maw fled just ahead of invading British troops via Thailand to Japan, where he was captured [9] later that year by the American occupation authorities and was held in Sugamo Prison until 1946. He then was allowed to return to Burma, after Burma became independent of Great Britain. He remained active in politics. He was jailed briefly during 1947, on suspicion of involvement in the assassination of Aung San, but was soon released.[citation needed]

After General Ne Win (1910–2002) took over power in 1963, Ba Maw was again imprisoned (like many prominent Burmese of the period who were detained during the time of Ne Win regime, from the 1960s to the 1980s, his imprisonment was without charge or trial) from about 1965 or 1966 to February 1968. During the period of his imprisonment Ba Maw managed to smuggle out a manuscript of his memoirs of the War years less than two of which (from 1 August 1943 to March 1945) he was Head of State (in Burmese naing-ngan-daw-adipadi, lit. 'paramount ruler of the State').[citation needed]

He never again held political office. His book Breakthrough in Burma: Memoirs of a Revolution, 1939–1946, an account of his role during the war years, was published by Yale University Press (New Haven) in 1968. In the post-war period he founded the Mahabama (Greater Burma) Party. He died in Rangoon on 28 May 1977.[citation needed]

Family

Ba Maw married Khin Ma Ma (13 December 1905 – 1967) on 5 April 1926.[10] The couple went on to have 7 children including Binnya Maw and Tinsa Maw.[10] His daughter Tinsa Maw married Bo Yan Naing of the Thirty Comrades in June 1944.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Riches, Christopher (2013). A Dictionary of Political Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ A History of Modern Burma (1958), p. 317

- ^ The Burma we love (1945), In a school catering especially for Anglo-Burman boys, St. Paul's English High School, it was considered superior not to be of full native blood. It was rumoured that he had some Armenian or European blood. This rumour was strengthened by the fact that one Thaddeus, an Armenian, occasionally visited the two boys in school on behalf of the mother who was living Maubin; colour was also lent to this rumour by the fair complexion of the two boys, a complexion much fairer than that of most of the Anglo-Burman boys in the school. It seems, however, that both their parents were of pure Mon blood.

- ^ Ferguson, John (1981). Essays on Burma. Brill Archive.

- ^ "Ba Maw - Oxford Reference". www.oxfordreference.com. doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095444112. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "Burma's First Prime Minister". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 456 Random House New York 1970

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 p 457 Random House New York 1970

- ^ He was captured on 18 January 1946

- ^ a b "Dr. Ba Maw's Biographic Timeline". Dr. Ba Maw Foundation. 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

Bibliography

- A History of Modern Burma, by John Frank Cady, Cornell University Press, 1958

- The Burma we love, by Kyaw Min, India Book House, 1945

- Allen, Louis (1986). Burma: the Longest War 1941-45. J.M. Dent and Sons. ISBN 0-460-02474-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - A Burmese heart, by Tinsa Maw-Naing, [Published by] Y.M.V. Han, 2015. [3],315 pages, with black and white illustrations. ISBN 9780996225403.

External links

- Speech of Ba Mow, Nippon News, No. 113. in the official website of NHK.

- Dr. Ba Maw Library, contains various pieces of documentary by and about Dr. Ba Maw. Run by the Dr. Ba Maw Foundation

- 1893 births

- 1977 deaths

- Asian fascists

- Administrators in British Burma

- Burmese collaborators with Imperial Japan

- Burmese nationalists

- Burmese Roman Catholics

- Burmese people of Mon descent

- University of Yangon alumni

- World War II political leaders

- Government ministers of Myanmar

- Heads of regimes who were later imprisoned

- Burmese prisoners and detainees

- Prisoners and detainees of Myanmar

- People from Ayeyarwady Region

- State of Burma

- University of Calcutta alumni

- Burmese revolutionaries

- Fascist rulers

- Burmese people of World War II

- Christian fascists