History of the Port of Southampton

| History of the Port of Southampton | |

|---|---|

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Location | Southampton, Hampshire, England |

| Coordinates | 50°53′47″N 1°23′48″W / 50.8965°N 1.3968°W |

| Details | |

| Operated by | Associated British Ports (ABP) |

| No. of berths | 45 (20–207) |

| Statistics | |

| Website ABP | |

The Port of Southampton is a major passenger and cargo port located in the central part of the south coast of England. It has been an important port since the Roman occupation of Britain nearly two thousand years ago, and has a multifaceted history. From the Middle Ages to the end of the 20th century, it was a centre for naval shipbuilding and a departure point for soldiers going to war. The port also played a role in the development of hovercraft, flying boat services, seaplanes and the Spitfire fighter plane. Before the advent of jet travel, Southampton was Britain's gateway to the world. The port also played a minor role in the history of Britain's canals.

History

There is evidence of settlement in the area now known as Southampton as far back as the Stone Age, but no evidence of boating or port activity. The Romans settled the site (known as Clausentum, now the Bitterne Manor area of Southampton) around 70 AD.[1] They operated a busy port, serving the large towns of Winchester and Salisbury. The settlement was abandoned when the Romans left Britain in 407 AD. The (Saxons ) founded a new town (known as Hamwick, later Hamtun) across the river Itchen from the Roman site around 700 AD. The population reached about 5,000, making it a large town.[1] The port traded with France, Greece and the Middle East, exporting wool and importing wines and fine pottery.

Legend has it that while in Southampton (although Bosham, West Sussex makes a similar claim),[2] Viking king Cnut the Great (also known as King Canute) sat on the shore on his throne and commanded the incoming tide to stop and not wet his robes. The tide ignored him. He was not trying to prove he was all-powerful, but was demonstrating to his courtiers that even he was not all-powerful; they should worship God instead. In 1016, Canute was crowned King of England in Southampton; although he had come as an invader, his twenty-year reign was peaceful and uneventful.[3] The port's 200-ton (tonne) floating crane, HLV Canute, was named after him.[4]

The Saxon town began to decline during the 10th century (due to Viking raids and the silting of the river Itchen), but a mediaeval town also known as Hamtun grew up nearby.[1] A large number of Norman immigrants arrived after the conquest, and English and French quarters developed in the town.[1] The most important import and export were still wine and wool, respectively.[1] The port was also an important departure point for English armies on their way to France.[1]

A shipbuilding industry began, constructing naval ships for the Hundred Years' War.[1] The most notable ship built during this era was HMS Grace Dieu,[5] the flagship of King Henry V. She was built in 1418 by William Soper, a burgess of Southampton and clerk of the king's ships, in a dock built for the purpose near Watergate Quay. This quay, dating from 1411 on the site now occupied by Town Quay, was the centre of the town's port activities. She was more than two hundred feet (61 m) long, with a displacement of around 2,750 tons (tonnes) (making her similar in size but different in appearance from HMS Victory). She was destroyed by fire on the river Hamble in 1439. Trade with Genoa and Venice began and flourished, traders bringing luxuries (such as perfumes, spices and silk) and cargoes of alum and woad (used to dye wool) and returning with English wool and cloth.[1]

Southampton became one of England's most important ports, after London and Bristol.[1] The name 'Southampton' came into use partly to eliminate confusion between this Hampton (in the kingdom of Wessex) and another Hamtun/Hampton (in the kingdom of Mercia); the latter became Northampton.[6]

In 1620, the Pilgrim Fathers (also known as Pilgrims or English Separatists) departed from Southampton for North America on the Mayflower and Speedwell.[7] The Speedwell had come from Holland to meet the Mayflower before crossing together. However, she was leaky and put into Dartmouth and Plymouth for repairs. There are reports that crew members who did not want to make the voyage sabotaged her.[8] She was deemed too unreliable to attempt the crossing; personnel and stores were transferred to the Mayflower, who completed the passage alone.

The 16th and 17th centuries were another period of decline for Southampton, as other ports (such as London) competed for business. The Italian trade dwindled, and the port was generally quiet until the second half of the 18th century.[1] There was a period during which Southampton was better known as a fashionable spa town and sea-bathing resort than as a port.[9]

Modern era

Trade gradually increased, and soon the port was handling wine and fruit from Spain and Portugal; grain from Ireland and eastern England; woollen stockings from the Channel Islands; slate and building stone from Scotland; coal from Newcastle and Scotland, and timber from the Baltics.[1] Paddle steamers began passenger service to the Channel Islands and Le Havre in 1823.[1] They berthed at Watergate Quay, but could only do so at high tide. The original wooden Royal Victoria Pier was opened in 1833, and provided berthing facilities at all tidal depths.[10]

The opening of the railway to London in 1840 gave a boost to the port. Ships began arriving in numbers that overwhelmed the town's quays and wharves, and the first dock was inaugurated in 1843. This became known as the "outer dock" when a second, "inner" dock began use in 1851. Berths along the Itchen Quays, South Quay and Test Quays became available for use between 1875 and 1902. In 1890 Queen Victoria opened the Empress Dock, larger and deeper than earlier ones. Four dry docks for ship maintenance were constructed, opening in 1846, 1847, 1854 and 1879.[11] The Southampton Harbour Board Police was founded in 1847, and policed the port and its environs.[12]

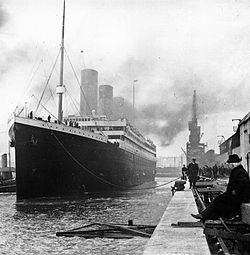

P&O was the first deep-sea shipping line to use the port, beginning service in 1840. Others moved in: the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company arrived in 1842, with service to South America; the Union Line began service to South Africa in 1857.[13] Of the trans-Atlantic companies, the American Line was first in 1893; White Star moved in from Liverpool in 1907, followed by Cunard in 1919. Another large dock was constructed, opening in 1911 and completing the 170-acre (69 ha) Eastern Docks system. First known as the White Star Dock, its name was changed[14] to Ocean Dock in 1922 when Cunard and Canadian Pacific also used it. In 1892 the Royal Pier reopened (now built of iron instead of wood). That year, the London and South Western Railway (which had greater financial resources than the Southampton Dock Company) became owner and operator of the docks.[15]

Many new ships were too big for the four dry docks, so a fifth (the largest in the world) was constructed in 1895. When ships outgrew that, a sixth (larger) dock was opened. The sixth dock was extended twice, and a notch was cut in the end (shaped like a ship's bow). When ships grew larger still, a floating dry dock was ordered from Armstrong Whitworth in Newcastle. Announced in 1922,[16] it arrived in 1924, and was based at Berth 50. It measured 960 by 134 ft (293 by 41 m) and was extendable, although it was the largest such structure in the world. To use the facility, seawater would be allowed into its internal tanks to partially submerge it; a ship sailed in and the water would be pumped out. This raised the dock, taking the ship out of the water for repairs and maintenance.[17] It could accommodate large ships such as the RMS Aquitania, but not very large ships such as the future RMS Queen Mary. The dock was moved to Portsmouth during the Second World War, and in 1959 it was sold to Rotterdam. In 1983 it was sold to Brazil, but it sank on the way there.[18]

The "New Docks" opened in 1934; this was actually a single quay 7,542 ft (2.299 km) along with 400 acres of associated reclaimed land. At the western end of this was the seventh dry dock, the King George V Graving Dock, which opened in July 1933.[19] The New Docks could accommodate the Queen Mary or the RMS Queen Elizabeth, the largest passenger ship to be built for 56 years. The New Docks are currently known as the Western Docks. West of the dry dock, a container port was developed from 1969–1997 in response to the increased use of containers.

At the Ocean Dock, the Art Deco Ocean Terminal opened in 1950 to provide shore facilities for the Queens and other Atlantic liners. These included an interior finished in blond burr woods, waiting rooms, baggage areas, spectator galleries, press rooms for journalists and three power-operated, telescoping gangways. Other amenities included buffets, a currency exchange, railway booking offices, telephone kiosks, newspaper stands and shops selling flowers, books and last-minute items. It was a luxurious facility by the standards of the day, and media interest in travelling celebrities added to its glamour. Downstairs were trains to London and facilities for luggage and ships' stores.[20][21] The Ocean Terminal was demolished in 1983. The Queen Elizabeth II passenger terminal was opened in 1966 to augment (and replace) it, which remains in regular use. That terminal in turn is augmented by the 2009 Ocean Terminal, across the dock from the old.

The inter-war period was a busy time for the port, which was called the "Gateway to the Empire". In 1936, the Southampton docks handled 46 percent of the UK's ocean-going passenger traffic.

The following facts and figures are from the 1938 Handbook to Southampton Docks:

- Passengers : 560,000

- Visitors: 500,000

- Cruise passengers: 70,000

- Passenger trains: 2,500

- Shipping: 18.5 million tons

- Shipping lines: 32

- World ports served: 160

Southampton also handled a large amount of cargo; nearly 90 percent of South Africa's fruit exports to the UK was handled at the port. Express freight trains enabled produce landing at Southampton in the morning to be on sale in London fruit markets in the afternoon:

- Fruit: over seven million packages (including 1.5 million bunches of bananas)

- Wagons: 160,000

- Freight trains handled: 4,200

Dock facilities:

- Total length of quays: 29,000 ft (8.8 km)

- Dry docks: 7

The King George (No. 7) dry dock was the largest in the world, and could accommodate liners of up to 100,000 tons:

- Cranes: 140

- Electric platform trucks (for moving cargo): 61

Museums

Southampton's maritime museum was originally housed in The Wool House on the edge of Town Quay which included a small exhibition about the Titanic. To mark the centenary of the Titanic's voyage a larger exhibition, "Southampton’s Titanic Story", has been developed for a new £15 million museum in the city centre. Opened in April 2012, SeaCity Museum also houses a permanent exhibition entitled "Gateway to the World".[22]

Southampton's archaeology museum was built into the city wall on the south shore in 1417 as a military fortification. The firing platform was on the roof, with guns and ammunition stored below. Later, it would be used as the town's gaol and was named God's House Tower after the neighbouring God's House hospital founded in 1196. The Roman, Saxon and mediaeval periods each have a gallery in the museum. Next to it is the Southampton Old Bowling Green (the world's oldest), dating from 1299.

To the west of the city wall (where the originals would have been moored), there is a replica of a wide-beamed cargo boat that was used for shipping wine and wool during the 14th century. It is set into the pavement (Southampton Docks is on reclaimed land), and may be viewed at any time.[23] There is also a replica of a similar boat in the early stages of construction, illustrating the construction techniques used.

The Mediaeval Merchant's House, in French Street, was built in 1290 as the home and business of wine merchant John Fortin. It contains period furnishings. Tudor House Museum and Garden, a large, striking 15th-century timber-framed house, is considered the city's most important historic building and re-opened after renovations in summer 2011.

Flying boats and seaplanes

Flying Boats operated passenger and mail service from Southampton between 1919 and 1958. At that time, runways suitable for large aircraft were scarce and aeroplane engines less reliable; in the event of engine trouble, passengers and crew were safer over water in a marine hull than a craft with wheels and a lightweight frame.

The first service in 1919 flew from the Royal Pier to Bournemouth and the Isle of Wight. During the 1920s, flights operated from Woolston to Northern France. Aircraft technology improved, and in 1937 Imperial Airways began service to East and South Africa and the United States. There was later additional service to destinations including Australia, Tokyo, Karachi, Singapore and Hong Kong.[24][25]

In 1937 aircraft were maintained at the Hythe flying-boat base; the terminal was at Berth 101, in the western docks. In 1938, passenger operations were conducted from Berth 108 in the new docks. In September 1939, aircraft and services were transferred to Poole Harbour under the direction of National Air Communications by BOAC (evolving from the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd). Post-war service operated from Berth 50 in the old docks. In 1950 BOAC ceased its flying-boat operations, but Aquila Airways continued service until 1958.[24][26] A Short Sandringham flying boat is on display at Solent Sky.[24]

The Supermarine works in Woolston was known for its success in the Schneider Trophy races, especially its three consecutive wins in 1927, 1929 and 1931. From his experiences with seaplanes Reginald J. Mitchell became chief designer of the Supermarine Spitfire fighter, which played a prominent role in World War II. A Spitfire and a Supermarine S.6A are also on exhibit at Solent Sky.

Military Southampton

Southampton has a history as a departure point for soldiers dating to Henry V's departure for Agincourt in 1415.[27] It has been heavily involved in most of the wars Britain has fought.

It was the point of departure for troops heading for the Crimea and the British Expeditionary Forces heading for France in both World Wars. It was also the major port of embarkation for troops and materiel involved in Operation Overlord in 1944.[28]

The Marchwood Military Port, built in 1943, is the base for the 17 Port and Maritime Regiment of the Royal Logistic Corps and home port for several Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships. It is the country's only facility equipped to accept all military vehicles from army bases (by rail or road) and load them on ships destined for war zones. The port played a major role despatching ships with vehicles and equipment in the 1982 Falklands conflict, receiving eighty war dead at its conclusion. RFA Sir Galahad, sunk at Fitzroy, and her sister ships were based here. In October 2010, it was announced that ownership would transfer from the Ministry of Defence to a private contractor as a cost-saving measure.[29]

Two of Southampton's best-known liners the Cunard Line RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 and the P&O liner SS Canberra played major roles in the Falklands war effort; the latter received an enthusiastic welcome upon her return.

The Watergate Quay area was a centre for the building of naval warships during the mediaeval period, while naval and merchant ships were built in the Redbridge area during the 18th century.[30] From 1904 to 2004 the John I. Thornycroft shipyard occupied a large site in Woolston, at the eastern mouth of the Itchen, building warships for the Royal Navy and others; the company was particularly busy before and during the two World Wars. It merged with Vosper & Company of Portsmouth in 1966, and the Woolston yard closed in 2003. Smaller shipyards, such as Husband and Day Summers & Co., also participated in the war effort.

Ship classes built in Woolston include:

- Coastal Motor Boat

- Thornycroft type destroyer leader

- Thornycroft M-class destroyer

- Type IV Hunt-class destroyer

- Landing Craft Assault

Cross-channel ferries

Cross-channel passenger steamers had moved from the Royal Pier to the Outer and Inner Docks when the latter opened. Their destinations included Le Havre, Cherbourg, St Malo and the Channel Islands. Most passengers arrived at the docks by train.

During the 1960s, the port operators and shipping lines realised that passengers wanted to take their cars on their travels. The passenger-only service ceased in 1964 with the arrival of the first roll-on/roll-off car ferry service. The vessels Viking I and Viking II of Thoresen Car Ferries ran to Le Havre and Cherbourg. and Viking III soon joined them along with a freight-only ferry Viking IV in 1967, during the summer peak a further vessel, Free Enterprise II, would relocate to the port to offer extra sailings to Cherbourg. By the early 1970s it was realised that the original Vikings had become too small so were therefore replaced by larger vessels the twin sisters MV Viking Venturer in 1974 and MV Viking Valiant in 1975. Townsend Thoresen ceased all remaining passenger operations from the port on 31 December 1983 transferring to nearby Portsmouth, the freight only service to Le Havre remained at the port until November 1984 when it too moved to Portsmouth thus ending the history of the company sailing from the port.

In the summer of 1966 a very short lived ferry service to Vigo, Lisbon and Gibraltar operated by the Norwegian company Klosters later to become NCL with their brand new cruiseferry MV Sunward operating from a new ferry terminal and linkspan at berth 49, it only lasted four months. A year later the major British shipping company P&O along with the French owned S.A.G.A. group formed Normandy Ferries both equal partners at the time and began service to Le Havre in 1967 with the British-flagged MV Dragon and followed by a sister a year later in 1968, the French-flagged MV Leopard. Other routes followed, including Swedish Lloyd's crossing to Bilbao with MS Patricia and some peak summers MS Hispania, the Bilbao route lasted for 10 years from 1967 to 1977. (P&O) Southern Ferries cruiseferry service on MV Eagle linking Southampton with Lisbon and Tangier later added to Algeciras and in 1973 commenced a service to Pasajes for San Sebastian in Spain with the smaller MV Panther which was the former German ferry MV Nils Holgerson built in 1965 for TT Line, both these routes closed in 1975. The Spanish shipping company Aznar Line commenced a service to Santander in May 1974 with the luxury cruise ferry MV Monte Toledo and a year later she was joined by a sister ship, MV Monte Granada, these two ships were sold to Libya and the service ceased in September 1977, there was also a short lived freight only roll-on/roll-off service to Le Havre, operated by Seagull Ferries, which ran from 1972 to 1974 with the sisters MV Saint Cristophe and MV Saint George using a linkspan at berth 49. During the peak years from 1973 to 1975 there was approximately 54 crossings a week to France, Morocco, Portugal and Spain from the Princess Alexandra Dock ferry terminals where there were four roll-on/roll-off berths three with a linkspan at berths 2, 3 and 7, berth 1 had a cut in the quay rather than a linkspan which is still visible today, with growth forecasted a further linkspan was added in 1977 at berth 30.[31]

Structural changes to the docks were made in preparation for the switch. In 1963, the entrance to the Outer Dock was widened; the Inner Dock and the oldest dry dock, by now too small for the latest ships, were filled in to provide car storage for the new service. Facilities for loading the cars onto the ferries were installed, and a timber-arched passenger-reception hall was built. The dock, named for Princess Alexandra, was opened by the Princess in July 1967.

However, by 1984 all ferry services had either closed or moved to Portsmouth. In 1991, Stena Sealink restarted service to Cherbourg. The vessel used was MV Stena Normandy (formerly MV St Nicholas). For six months during 1992, the smaller MV Stena Traveller provided additional freight capacity.[32] The service was under-utilised towards the end and with the recent opening of the Channel Tunnel plus the loss of duty-free sales and declining freight it was decided that after the lease of the vessel expired that the service would stop and it ceased on 27 October 1996.

A short-lived twice daily in each direction freight ferry service to the port of Radicatel on the River Seine near Rouen with CFL Channel Freight Ferrys Ltd ran from January 2004 but ceased operating just over a year later, this service operated from the former Stena Line terminal at berth 30 using the ro/ro freight ferrys MV CFF Seine and MV CFF Solent.

There are currently no cross-channel ferries operating from Southampton; most service in the region runs from Portsmouth, 20 miles (32 km) to the east, which has become the nation's second-most-important ferry port (after Dover). The operators' rationale for the move was based on cost-effectiveness. Poole, 30 miles (48 km) west, hosts the remaining service. The vacated dock became the Ocean Village development with a marina for 375 yachts, residential apartments with moorings and a home for the Royal Southampton Yacht Club. It has been a venue for major yacht races; the start of seven (and finish of four) Whitbread (now Volvo) round-the-world races took place at Southampton between 1977 and 2001, and the Global Challenge started from the port in 1992, 1996 and 2000. The area includes shops, homes, offices, bars, restaurants, a multiplex and an art house cinema designed to resemble an ocean liner.

The National Oceanography Centre opened south of the vacated area in 1996. The large facility is a hub of national marine-science activity and home to several departments of the University of Southampton. It houses the UK's collection of subsea sediment cores and is the base for oceanographic-research ships RRS Discovery and RRS James Cook.

Cross-Solent hovercraft

In July 1966, British Rail Hovercraft began its Seaspeed hovercraft service between Cowes and Southampton with two SR.N6 craft. The Cowes terminal was located on Medina Road, and the Southampton terminal on Crosshouse Road next to the Woolston Floating Bridge ramp; the site is currently under the western end of the Itchen Bridge. During the winter of 1971–72, both craft were lengthened by 10 ft (3.0 m) and named the Sea Hawk and Sea Eagle. Each craft's capacity was increased from 36 to 58 passengers. The service transferred to Hovertravel of Ryde in 1976, who operated it until the end of 1980.[33]

In 1981, Red Funnel acquired two Hovermarine HM2 Mk III SES craft from Hovertravel. They primarily worked as charters to Vosper Thornycroft, transporting workers from the Isle of Wight to the Woolston shipyard.[34] This service was not available to the public, but the craft occasionally appeared on the Fast Passenger Ferry Service (usually operated by Shearwater Hydrofoils). The hovercraft were gone by 1982, made redundant by the arrival of Shearwater 6.[35]

In May 1990 the Cowes Express company began operations from Southampton Town Quay to Cowes with its craft, the Sant' Agata. After several weeks, service ended following mechanical problems; a year later, the company returned with the renamed Sant' Agata (Wight King) and its running mate, Wight Queen. They were Cirrus 120P surface effect ships, built in Norway by Brødrene Aa Båtbyggeri, carrying up to 330 passengers at a speed of 50 knots. A smaller backup craft, the Wight Prince, was also leased: a Dutch-built Seaswift 23 with a capacity of 99 passengers at 36 knots. These machines (and the HM2s) were catamarans with twin rigid hulls and flexible skirts fore and aft. With the lift fans of a conventional hovercraft, they were propelled by waterscrews or waterjets instead of propellers. The vehicles were quieter than conventional hovercraft, and more resistant to being pushed sideways by wind or water. Their disadvantage was that they were not amphibious, and could not leave the water.

Service was reliable and popular; however, its Southampton terminal was leased from ABP (owner of rival Red Funnel). Competitive fares and service brought Cowes Express a larger share of the foot-passenger market than Red Funnel; the latter raised its rent, bankrupting the company in spring 1992.[36]

Canals

Andover Canal

A 22-mile (35 km)-long canal linked Redbridge (at the western end of the port area) with Romsey, Stockbridge and Andover from 1790 to 1859. It was then filled in, and a railway (which became known as the Sprat and Winkle Line) was built over it for much of its length; the line was used extensively during World War II and lasted until 1967. Remnants of the canal and railway survive.[37]

Salisbury and Southampton Canal

A second, less-successful canal was planned to link Southampton with Salisbury.[38] It used the Andover canal for nine miles (14 km) from Redbridge to a new junction between Kimbridge and Mottisfont. From there it went west towards Salisbury, and terminated at Alderbury Common. Here, a horse-drawn railway was constructed to bring goods to the existing road and the last few miles were completed by wagon.

The 4+1⁄2-mile (7.2 km) eastern section of the canal began in Redbridge, at a junction near the end of the Andover canal. It followed the shore of the River Test to the town, and went through a tunnel near the present railway tunnel (1 foot, 300 mm) below it, where the tunnels obliquely cross). It divided after emerging: one branch went south to the shore near the God's House Tower (a gaol at the time) and the other ran northeast to the coal depots of the Itchen near the Northam bridge, providing a link to Itchen navigation.

The paradox of constructing a canal so near a navigable waterway was lampooned in contemporary verse:

Southampton's wise sons found their river so large,

Tho' 'Twould carry a Ship, 'twould not carry a barge.

But soon this defect their sage noddles supply'd,

For they cut a snug ditch to run close by its side.

Like the man who, contriving a hole through his wall

To admit his two cats, the one great, t'other small,

Where a great hole was made for great puss to pass through,

Had a little hole cut for his little cat, too.

The contemporary rationale was:

- During the eighteenth century the Test estuary was shallow, marshy, silted and difficult to navigate, with mud flats near its shore. Only during the twentieth century, with the construction of the New Docks, it would be dredged and drained to become a deep harbour.

- Different types of craft (seaworthy sailing vessels and horse-drawn, flat-bottomed, shallow barges respectively) were needed for marshy estuaries and canals.

- There was only one landing point on the route, at Millbrook; boats on the canal could load and unload at any point, which was considered important in this urban area. The canal would also provide better protection than the estuary from poor weather and sea conditions.

- Its promoters envisioned the canal as the centre of a future network of canals; however, that never happened.[40]

The canal was unsuccessful, and there was never a time when all portions were open simultaneously. There were serious engineering and financial problems, including bankruptcies. After a few years it began to deteriorate, and between 1820 and 1851 it was filled in and grassed over.[41] Many Southampton residents are unaware of the city's canal history; only a few street names (such as Canal Walk) remain. In the rural section between Kimbridge and Alderbury there are a few structural remains, and in some locations the canal bed can be seen.

Itchen Navigation

From the tidal area of the Itchen at Woodmill Bridge the river route continues to Winchester, nine miles (14 km) upstream. Partly because of its link to the sea, Winchester was the nation's capital (or second city) for 500 years. The Itchen Navigation, a canal system that bypassed stretches of the river difficult to navigate, was open from 1710 to 1869 for transporting agricultural produce and coal. A conservation project for the canal has begun.

See also

- Port of Southampton (present port)

- Southampton (city)

- History of Southampton (history of the city)

- Category:Ships built in Southampton

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lambert, Tim. "A Brief History of Southampton". Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "King Canute of Bosham". Bosham Online Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Jones, Martin BA. "InfoBritain – King Canute". Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ "ABP Port of Southampton -Master Plan 2009 – 2030" (PDF). 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "National archives – Grace Dieu 1420". Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Lambert, Tim. "A brief history of Northampton". Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "Voyage of the Mayflower and the Speedwell". Archived from the original on 23 October 1999. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Usher R G 1984 The Pilgrims and their History Corner House Publishers ISBN 0-87928-082-4 p 67

- ^ Hembry, Phyllis May (1990). The English spa, 1560–1815: a social history. ISBN 9780838633915. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Boyle, Ian (1999–2007). "Hampshire Piers". Simplon – The Passenger Ship Website. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Port Cities – Southampton". Southampton City Council. 2002–2005. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Head, Viv (17 May 2011). "Southampton Harbour Board Police 1847 – 1980". Website of the British Transport Police History Group. British Transport Police History Group. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "History of Union-Castle Line and its Predecessors (1857–1977)". The AJN Transport Britain Collection. 2005. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Port Cities – Southampton". Southampton City Council. 2002–2005. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Whitbread, J.R. (1961). The Railway Policeman: The Story of the Constable on the Track. London: G.G. Harrap. p. 234.

- ^ "Floating dock to lift 60,000 tons". Dundee Courier. 27 September 1922 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Port Cities – Southampton – Berths 49 – 51". Southampton City Council. 2002–2005. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Dreadnought. "World Naval Ships". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Mammoth new dry dock: Opening ceremony bu the King: Southampton triumph". Gloucester Citizen. 19 July 1933 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Southampton Ocean Terminal". The AJN Transport Britain Collection. 2005. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Port Cities – Southampton – Ocean Dock". Southampton City Council. 2002–2005. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Southampton Sea City Museum Receives Grant". Museum Publicity. 2 August 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Catford, Nick. "Southampton Flying Boat Terminal". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ G, Dave. "Southampton Flying Boat Services 1919–1958". Archived from the original on 1 July 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Flying Boat Services from Southampton www.portsandships.com

- ^ http://www.portsandships.com/index.php?categoryid=14&p2_articleid=5

- ^ Kemp, Anthony (1984). Springboard for Overlord. Horndean: Milestone Publications. ISBN 0-903852-42-X.

- ^ Yandell, Chris (5 November 2010). "Marchwood Military Port to stay open but under private ownership". Southern Daily Echo. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Cox 1738 cited in Hampshire Gazeteer (2001). "Redbridge, Southampton". Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ferry Galleries". Simplon – The Passenger Ship Website. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Stena Challenger & Stena Traveller". Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "The Hovercraft History and Hovercraft Museum Website". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Classic Fast Ferries" (PDF). March 2001. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Red Funnel Vessel Archive 1981–2010". Retrieved 19 November 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Ships Nostalgia (registration required)". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Southampton Canal Society – Andover Canal". 2009 [2005]. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Southampton Canal Society – Local Waterways". 2003 [1999]. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Fisher, Stuart (2012). Rivers of Britain: Estuaries, tideways, havens, lochs, firths and kyles. London: A & C Black. p. 268. ISBN 9781408159316. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Southampton Canal Society – Southampton and Salisbury Canal – Which Route?". 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "Southampton Canal Society – S&S Canal – The Aftermath". 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2010.