Falastin

| |

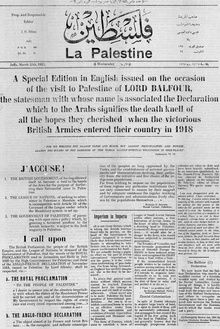

Cover of Falastin (9 May 1936), with the headline story reporting on the Arab revolt in Palestine | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Founder(s) | Issa El-Issa |

| President | Daoud El-Issa |

| Editor | Yousef El-Issa Raja El-Issa Yousef Hanna |

| Founded | January 15, 1911 |

| Political alignment | Anti-Zionism Palestinian nationalism |

| Language | Arabic English |

| Ceased publication | February 8, 1967 |

| City | Jaffa East Jerusalem |

| Country | Ottoman Empire Mandatory Palestine Jordanian West Bank |

| Circulation | 3,000 (1929)[1] |

Falastin, sometimes transliterated Filastin, (Arabic: فلسطين) was an Arabic-language Palestinian newspaper. Founded in 1911 from Jaffa, Falastin began as a weekly publication, evolving into one of the most influential dailies in Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine.

As Palestine's most prominent newspaper, its circulation was estimated to be 3,000 in 1929–the year it became a daily. Although a modest figure, it was almost double that of its nearest competitor. However, Falastin's standing was challenged in 1934 by the Jaffa-based Al-Difa' newspaper, which soon surpassed it in circulation. Both dailies witnessed steady improvements, and their competition marked Palestinian public life till 1948.

Falastin was founded by Issa El-Issa, who was joined by his paternal cousin Yousef El-Issa. Both El-Issas were Arab Christians, opponents of Zionism and British administration. The newspaper was initially focused on the Arab struggle against Greek clerical hegemony of the Jerusalem Orthodox Church. It was also the country's fiercest and most consistent critic of the Zionist movement, denouncing it as a threat to Palestine's Arab population. It helped shape Palestinian identity and was shut down several times by the Ottoman and British authorities, most of the time due to complaints made by Zionists.

Falastin, fleeing the fighting in Jaffa during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, relocated to East Jerusalem in the West Bank which then became under Jordanian control. The newspaper continued to be published until 1967 when it was merged with Al-Manar to produce Jordanian-based Ad-Dustuor newspaper in Amman that is still published to this day.[2]

History

Falastin was established on 14 January 1911 by Issa El-Issa and Yousef El-Issa, two Arab Christian cousins from the coastal city of Jaffa in Palestine. It was among a handful of newspapers to have emerged from the region following the 1908 Young Turk Revolution in the Ottoman Empire which lifted press censorship. The newspaper was initially focused on the Orthodox Renaissance, a movement that aimed to weaken the Greek clerical hegemony over the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, so that its vast financial resources could be utilized to improve education for the Arab Christians of Palestine. Other topics addressed in the newspaper included modernization, reforms and improving the welfare of the peasants. Its geographic scope of interest focused on the Mutassarifate of Jerusalem, primarily news from Jaffa and Jerusalem, but also less frequently Hebron, Jericho and Gaza. The scope of interest later expanded in 1913 to include all of Palestine.[3]

Issa El-Issa, a graduate of the American University of Beirut, worked in several places before establishing Falastin. He came from a Palestinian family known for its 'intellect, politics and literature'.[4] The family was financially independent from the Jerusalem Patriarch's charity as it had historically invested in olive oil and soap trading. Issa's cousin Hanna El-Issa, was editor of the short-lived Al-Asma'i magazine which was first published in Jerusalem on 1 September 1908. Much less is known about Hanna's brother Yousef, who was Falastin's editor-in-chief between 1911 and 1914. During World War I, both Issa and Yousef were exiled to Anatolia. Issa became head of King Faisal's Royal Court after the Arab Kingdom of Syria was established in 1920. After the Kingdom's defeat by French forces the same year, Issa returned to Jaffa where he was allowed to republish Falastin in 1921. Issa's son Raja El-Issa took over publishing the newspaper after 1938.[3]

Suspension

Working under the censorship of the Ottoman Empire and the British Mandate, Falastin was suspended from publication over 20 times.[6] In 1914, Falastin was suspended by Ottoman authorities, once for criticism of the Mutasarrif (November 1913) and once for what British authorities summarized as "a fulminating and vague threat that when the eyes of the nation were opened to the peril towards which it was drifting it would rise like a roaring flood and a consuming fire and there would be trouble in [store] for the Zionists."[7]

Following the first suspension in 1914, Falastin issued a circular responding to the government charges that they were "sowing discord between the elements of the [Ottoman] Empire," which stated that "Zionist" was not the same as "Jew" and described the former as "a political party whose aim is to restore Palestine to their nation and concentrate them in it, and to keep it exclusively for them."[7] The newspaper was supported by Muslim and Christian notables, and a judge annulled the suspension on grounds of freedom of the press.[7]

After the newspaper was allowed to be republished, Issa El-Issa wrote in an editorial that "the Zionists still look at this newspaper with suspicion and consider it the greatest stumbling block that hinders their goals and informs people of their aspirations and what is discussed at their Congresses and what their leaders declare and their newspapers and magazines publish." Defending himself in the Ottoman court, he recounted saying "when we said 'Zionists' we referred to the political organisation with its headquarters in Europe which aims for the colonisation of Palestine, the usurpation of its lands and its transformation into a Jewish homeland". He emphasized his positive attitude towards Jews who he had called "brothers". The court identified with Issa and Yousef's arguments, the latter having testified in favor of his cousin Issa. The Al-Karmil newspaper reported that the crowds waiting inside and outside the courtroom erupted in applause after the verdict was pronounced, "signs of anger appeared on the faces of the Zionists much as signs of joy were visible on the faces of the natives." The French Consulate reported that jubilant crowds had carried the editors on their shoulders after the trial finished.[3]

Coverage of sport news

The establishment of Falastin newspaper in 1911 is considered to be the cornerstone of sports journalism in Ottoman Palestine. It is no coincidence that the most active newspaper, also reported on sporting events. Falastin, covered sport news in Ottoman Palestine which helped in shaping the modern Palestinian citizen, bringing the villages and cities together, building Palestinian nationalism and deepening and maintaining Palestinian national identity.[8][9][10][11][12]

Nashashibi-Husseini rivalry

On the rivalry between the Nashashibi and the Husseini families in Mandatory Palestine, an editorial in Falastin in the 1920s commented:[13]

The spirit of factionalism has penetrated most levels of society; one can see it among journalists, trainees, and the rank and file. If you ask anyone: who does he support? He will reply with pride, Husseini or Nashasibi, or. . . he will start to pour out his wrath against the opposing camp in a most repulsive manner.

Influence

Yousef El-Issa, the newspaper's editor-in-chief during its infancy, was described by a researcher to be "a founder of modern journalism in Palestine".[14] Al-Muqattam, one of the most read dailies in Egypt, commented in an editorial when Yousef was editor-in-chief (1911-1914):

Heads of Arabs in all major cities bend to the editorials of Ustad Yousef El-Issa.[14]

Albert Einstein's letter

On January 28, 1930 Albert Einstein sent out a letter to Falastin's editor Issa El-Issa.

- One who, like myself, has cherished for many years the conviction that the humanity of the future must be built up on an intimate community of the nations, and that aggressive nationalism must be conquered, can see a future for Palestine only on the basis of peaceful cooperation between the two peoples who are at home in the country. For this reason I should have expected that the great Arab people will show a truer appreciation of the need which the Jews feel to rebuild their national home in the ancient seat of Judaism; I should have expected that by common effort ways and means would be found to render possible an extensive Jewish settlement in the country. I am convinced that the devotion of the Jewish people to Palestine will benefit all the inhabitants of the country, not only materially, but also culturally and nationally. I believe that the Arab renaissance in the vast expanse of territory now occupied by the Arabs stands only to gain from Jewish sympathy. I should welcome the creation of an opportunity for absolutely free and frank discussion of these possibilities, for I believe that the two great Semitic peoples, each of which has in its way contributed something of lasting value to the civilisation of the West, may have a great future in common, and that instead of facing each other with barren enmity and mutual distrust, they should support each other's national and cultural endeavours, and should seek the possibility of sympathetic co-operation. I think that those who are not actively engaged in politics should above all contribute to the creation of this atmosphere of confidence.

- I deplore the tragic events of last August not only because they revealed human nature in its lowest aspects, but also because they have estranged the two peoples and have made it temporarily more difficult for them to approach one another. But come together they must, in spite of all.[15][16]

Falastin's Centennial

"Falastin's Centennial" was a conference that took place in Amman, Jordan in 2011. Twenty-four local, regional and international researchers and academicians examined Falastin's contribution to the 20th-century Middle East at the two-day conference, which was organised by the Columbia University Middle East Research Centre. The conference highlighted the Jordanian cultural connection to Palestine through various articles that featured Jordanian cities and news. The newspaper's founder Issa El-Issa was a close friend of the Hashemite family, Falastin covered the news of the Hashemites from Sharif Hussein to his sons King Faisal I and King Abdullah I and his grandson King Talal. The paper captured the late King Abdullah's relations with the leaders and people of Palestine, documenting every trip he made to a Palestinian town and every stand he took in support of Palestine and against Zionism. Correspondents of the newspaper in Jordan even interviewed the King in Raghadan Palace.

A participant in the conference stated that

Many people tend to dismiss it as only a newspaper, but in fact, it is mine of information and documents pertaining to the history of the Arab world.[6]

Gallery

-

Falastin's headquarters in Ajami neighborhood, Jaffa, 1938

-

Falastin's headquarters in Jerusalem, 1950s

See also

References

- ^ "Introduction: History of the Arabic press in the land of Israel/Palestine". National Library of Israel. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "[The newspaper] Filastin (Originally: Falastin)". National Library of Israel.

- ^ a b c Emanuel Beška (2016). From Ambivalence to Hostility: The Arabic Newspaper Filastin and Zionism, 1911–1914. Slovak Academic Press. pp. 27–29. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- ^ "Raja El-Issa obituary". Gerasanews.com. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ^ "Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt: Images of the Body in Political Cartoons of Mandatory Palestine". 1 January 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- ^ a b [1][dead link]

- ^ a b c Mandel, 1976, pp. 179-181

- ^ "View on sports in historic Palestine". Issam Khalidi. Jerusalem Quarterly. 2010-01-01. Archived from the original on 2011-01-25.

- ^ "Notations on the Evolution of an Arab and Arab American Media, and Arab Literature". Ray Hanania. The Media Oasis. 1999-10-10. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ Rashid Khalidi (2006-01-09). The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- ^ Mandel, 1976, pp. 127-130: "the Christian editors of Falastin would call on all Palestinians, both Muslim and Christian, to unite against Zionism on grounds of local patriotism"

- ^ Rugh, 2004, p. 138

- ^ "Filastin". National Library of Israel. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ a b Beska, Emanuel (2018). "Yusuf al-'Isa: A Founder of Modern Journalism in Palestine". Jerusalem Quarterly. 74 (74): 7–13.

- ^ Einstein, 2013, pp. 181-2

- ^ Rosenkranz, 2002, p. 98

Further reading

- Beška, Emanuel (2016). From Ambivalence to Hostility: The Arabic Newspaper Filastin and Zionism, 1911–1914. Slovak Academic Press. ISBN 978-80-89607-49-5.

- Bracy, R. Michael (2010). Printing Class: 'Isa al-'Isa, Filastin, and the Textual Construction of National Identity, 1911-1931. University Press of America. ISBN 0761853774.

- Einstein, Albert (2013). Einstein on Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism, Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-400-84828-8.

- Mandel, Neville J. (1976). The Arabs and Zionism before World War I. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02466-3.

- Rosenkranz, Ze'ev, ed. (2002). The Einstein Scrapbook. TJHU Press. ISBN 0801872030.

- Rugh, William A. (2004). Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275982122.

External links

- Defunct newspapers

- Newspapers published in the Ottoman Empire

- Newspapers published in Mandatory Palestine

- Publications established in 1911

- Publications disestablished in 1967

- Anti-Zionism in Mandatory Palestine

- Arab nationalism in Mandatory Palestine

- Palestinian nationalism

- 1911 establishments in the Ottoman Empire