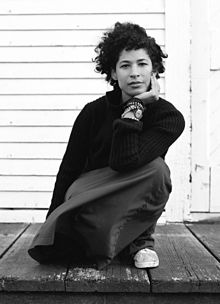

Rebecca Walker

Rebecca Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 17, 1969 Jackson, Mississippi, United States |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, feminist |

| Parent(s) | Alice Walker Melvyn Leventhal |

| Website | http://www.rebeccawalker.com/ |

Rebecca Walker (born November 17, 1969, as Rebecca Leventhal) is an American writer, feminist, and activist. Walker has been regarded as one of the prominent voices of Third Wave Feminism, and the coiner of the term "third wave", since publishing a 1992 article on feminism in Ms. magazine called "Becoming the Third Wave", in which she proclaimed: "I am the Third Wave."[1][2]

Walker's writing, teaching, and speeches focus on race, gender, politics, power, and culture.[3][4] In her activism work, she helped co-found the Third Wave Fund that morphed into the Third Wave Foundation, an organization that supports young women of color, queer, intersex, and trans individuals by providing tools and resources they need to be leaders in their communities through activism and philanthropy.[3]

Walker does extensive writing and speaking about gender, racial, economic, and social justice at universities around the United States and internationally.[5]

In 1994, Time named Walker as one of the 50 future leaders of America.[6] Her work has appeared in publications including The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, Salon, Glamour, and Essence and has been featured on CNN and MTV.[7]

Early life and education

Born Rebecca Leventhal in 1969 in Jackson, Mississippi, she is the daughter of Alice Walker, an African-American writer whose work includes The Color Purple, and Melvyn R. Leventhal, a Jewish American civil rights lawyer. Her parents married in New York before going to Mississippi to work in civil rights.[8] After her parents divorced in 1976, Walker spent her childhood alternating every two years between her father's home in the largely Jewish Riverdale section of the Bronx in New York City and her mother's largely African-American environment in San Francisco. Walker attended The Urban School of San Francisco.

When she was 15, she decided to change her surname from Leventhal to Walker, her mother's surname[9]. After high school, she studied at Yale University, where she graduated cum laude in 1992. Walker identifies as Jewish and Black; her 2000 memoir is titled Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self.[10]

Emergence as a leader in feminism

Walker first emerged as a prominent feminist at the age of 22 when she wrote an article for Ms. magazine titled "Becoming the Third Wave".[11][12][13] In her article, Walker criticizes the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas after he was accused of sexually harassing Anita Hill, an attorney whom he supervised during his time at the Department of Education and the EEOC. Using this example, Walker addresses the oppression of the female voice and introduces the concept of Third-wave feminism.[14] She defines "third-wave feminism" at the end of the article by saying "To be a feminist is to integrate an ideology of equality and female empowerment into the very fiber of life. It is to search for personal clarity in the midst of systemic destruction, to join in sisterhood with women when often we are divided, to understand power structures with the intention of challenging them."[15]

Activism

The Third Wave Fund

After graduating from Yale University, she and Shannon Liss (now Shannon Liss-Riordan) co-founded the Third Wave Fund, a non-profit organization aimed at encouraging young women to get involved in activism and leadership roles.[16] The organization's initial mission, based on Walker's article, was to "fill a void in young women's leadership and to mobilize young people to become more involved socially and politically in their communities."[17] In its first year, the organization initiated a campaign that registered more than 20,000 new voters across the United States. The organization now provides grants to individuals and projects that support young women. The fund was adapted as The Third Wave Foundation in 1997 and continues to support young activists. In the wake of the November 2016 presidential election in the United States, the organization received more than four times the normal number of requests for emergency grants.[18]

Teaching

Walker views teaching as a way to give people the strength to speak the truth, to change perspectives, and to empower people with the ability to change the world.[5] She lectures on writing memoirs, multi-generational feminism, diversity in the media, multi-racial identity, contemporary visual arts and emerging cultures.[5]

Speaking

Walker concentrates on speaking about multicultural identity (including her own), enlightened masculinity, and inter-generational and third-wave feminism at high schools, universities and conferences around the world. She has spoken at Harvard, Exeter, Head Royce, Oberlin, Smith, MIT, Xavier, Stanford,[7] and Louisiana State University.[19] She has also addressed organizations and corporations such as The National Council of Teachers of English, the Walker Art Center, the American Association of University Women, the National Women's Studies Association, Out and Equal, the National Organization for Women, and Hewitt Associates. In the United States, she has been featured on various popular media outlets such as Good Morning America, The Oprah Winfrey Show, and Charlie Rose.[7]

Books and writing

Major works

Walker's first major work was the book To be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (1996), which consisted of articles that she compiled and edited. The book reevaluated the feminist movement of the time. Reviewer Emilie Fale, an Assistant Professor of Communication at Ithaca College, described it: "The twenty-three contributors in To Be Real offer varied perspectives and experiences that challenge our stereotypes of feminist beliefs as they negotiate the troubled waters of gender roles, identity politics and "power feminism".[20] As a collection of "personal testimonies", this work shows how third-wave activists use personal narratives to describe their experiences with social and gender injustice.[21] Contributors include feminist writers such as bell hooks and Naomi Wolf. According to Walker's website, this book has been taught in Gender Studies programs around the world.[7]

In her memoir Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self (2000), Walker explores her early years in Mississippi as the child of parents who were active in the later years of the Civil Rights Movement. She also touches on living with two parents with very active careers, which she believes led to their separation. She discusses encountering racial prejudice and the difficulties of being mixed-race in a society with rigid cultural barriers. She also discusses developing her sexuality and identity as a bisexual woman.[22]

Her 2007 memoir Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After A Lifetime of Ambivalence explores her life with a stepson and biological son against a framework of feminism. She discusses traditional pregnancy topics, such as diet and preparing for labor. She encourages young women to understand that motherhood is possible even when they have a career or if they resist it because of having had a difficult childhood.[4] She says the book addresses the "work versus motherhood" trade-off that women of her generation and younger face after growing up in a social landscape that believes women must make a choice in order to have children.[4] She has said she was inspired to write the book by the birth of her son, Tenzin Walker. Her rearing of him has changed some of her views on motherhood and family bonds.[4] The book also revealed Walker's "tempestuous" relationship with her mother, Alice Walker; the two did not speak for a number of years as Rebecca was critical of how her mother viewed motherhood and treated her as a child.[23][24]

Walker was a contributing editor to Ms. magazine for many years. Her writing has been published in a range of magazines, such as Harper's, Essence, Glamour, Interview, Buddhadharma, Vibe, Child, and Mademoiselle magazines. She has appeared on CNN and MTV, and has been covered in The New York Times, Chicago Times, Esquire, Shambhala Sun, among other publications. Walker has taught workshops on writing at international conferences and MFA programs. She also works as a private publishing consultant.[7]

Her first novel, Adé: A Love Story, was published in 2013. It features a biracial college student, Farida, who falls in love with Adé, a black Kenyan man. The couple's plan to marry is interrupted when Farida gets malaria and the two must struggle through a civil war in Kenya. The novel was generally well received by critics and laypeople alike.[25]

Bibliography

- To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (1996) (editor)

- Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self (2000)

- What Makes A Man: 22 Writers Imagine The Future (2004) (editor)

- Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence (2007)

- One Big Happy Family: 18 Writers Talk About Polyamory, Open Adoption, Mixed Marriage, Househusbandry, Single Motherhood, and Other Realities of Truly Modern Love (2009) (editor)

- Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness (Soft Skull Press, February 2012) (editor)[26]

- Adé: A Love Story (2013), (novel)

Film

In the 1998 film Primary Colors, Walker played the character March. The movie is a roman à clef about Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign.

In March 2014, the film rights for her novel Adé: A Love Story (2013) were reported to have been optioned, with Madonna to serve as director.[27]

Awards

- Women of Distinction Award from the American Association of University Women,[28]

- "Feminist of the Year" award from the Fund for the Feminist Majority,

- "Paz y Justicia" award from the Vanguard Public Foundation,

- "Intrepid Award" from the National Organization for Women,[29]

- "Champion of Choice" award from the California Abortion Rights Action League,

- "Women Who Could Be President Award" from the League of Women Voters.

Walker has also received an honorary Doctorate from the North Carolina School of the Arts.[30]

Walker is featured in The Advocate′s "Forty Under 40" issue of June/July 2009 as one of the most influential "out" media professionals.[31]

In 2016, she was selected as one of BBC's 100 Women.[32]

Personal life

Walker identifies as bisexual. She had a relationship with neo-soul musician Meshell Ndegeocello, whose son she has helped raise even after the adults had separated.[33][9]

At the age of 37, she became pregnant during her relationship with her partner Glen, a Buddhist teacher. They had a son together named Tenzin Walker, born in 2004.[34]

Once estranged from her mother Alice Walker, she has reconciled with her, and the two have since appeared at literary events together.[24][35][36]

See also

References

- ^ HeathenGrrl's Blog: Becoming the Third Wave by Rebecca Walker

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (October 27, 2011). "Anita Hill Woke Us Up". HuffPost. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ a b "About". rebeccawalker.com. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Rosenbloom, Stephanie (March 18, 2007). "Alice Walker – Rebecca Walker – Feminist – Feminist Movement – Children". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Speaking". rebeccawalker.com. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Miller, Zeke J.; Lily Rothman (December 5, 2014). "What Happened to the 'Future Leaders' of the 1990s?". Time. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Full Biography". rebeccawalker.com. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- ^ Ross, Ross (April 8, 2007). "Rebecca Walker bringing message to Expo". Pensacola News Journal. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Rosenbloom, Stephanie (March 18, 2007). "Evolution of a Feminist Daughter". The New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (2000). Black, White, and Jewish: Autiobiography of a Shifting Self. Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573221696.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (1992). "Becoming the Third Wave". Ms. Magazine. 11 (2): 39–41.

- ^ Snyder, R. Claire (2008). "What Is Third‐Wave Feminism? A New Directions Essay". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 34 (1): 175–196. doi:10.1086/588436. ISSN 0097-9740.

- ^ The women's movement today : an encyclopedia of third-wave feminism. Heywood, Leslie. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. 2006. ISBN 0313331332. OCLC 60971806.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Walker, Rebecca (October 27, 2011). "Anita Hill Woke Us Up". HuffPost. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (February 28, 2007), "Becoming the Third Wave" by . HeathenGrrl's Blog. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Bazeley, Alex (April 21, 2016). "Third-Wave Feminism". Washington Square News. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ History Archived October 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Third Wave Foundation. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to Third Wave Fund!". Third Wave Fund. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ lsu.edu https://www.lsu.edu/hss/wgs/files/newsletterspr2005.pdf. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "To Be Real". rebeccawalker.com. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Fisher, J. A. (May 16, 2013). "Today's Feminism: A Brief Look at Third-Wave Feminism". Being Feminist. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (2000). "Nonfiction Book Review: Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self". Publishers Weekly. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-169-6. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Rebecca (March 4, 2008). Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence. Penguin. ISBN 9781440662836.

- ^ a b "Rebecca Walker Explains Rift With Mother, Alice". NPR. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Schultz, Laurie. "Review: Adé: A Love Story". nyjournalofbooks.com. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Staff (December 12, 2011). "Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness. Edited by Rebecca Walker", Publishers Weekly.

- ^ Kellogg, Carolyn (March 25, 2014). "Madonna to film Rebecca Walker's 'Ade: A Love Story'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Women of Distinction Program Archived June 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ NOW's First Annual Intrepid Awards Gala: Rebecca Walker Archived November 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Now.org. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Dorsky, Kait. "Guides: UNCSA History: Honorary Doctorates". library.uncsa.edu. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ "Forty Under 40". The Advocate. June–July 2009. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ "BBC 100 Women 2016: Who is on the list?", BBC News, November 21, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ Maran, Meredith (May 28, 2004), "What Little Boys are Made of", Salon, retrieved April 7, 2011

- ^ Krum, Sharon (May 26, 2007). "Can I survive having a baby? Will I lose myself ... ?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ PhD, Nsenga K. Burton (August 1, 2019). "Alice Walker: Hometown Celebrates Literary Legend's 75th Birthday". BlackPressUSA. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Sneed, Shannon (July 18, 2019). "Alice Walker comes home". Eatonton Messenger. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

External links

- "Becoming the Third Wave" by Rebecca Walker

- Curry, Ginette. "Toubab La!": Literary Representations of Mixed-race Characters in the African Diaspora, Newcastle, England: Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2007.

- Official site

- Official Myspace page

- Rebecca Walker at IMDb

- Third Wave Foundation

- Rebecca Walker, Excerpt: Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self, The Multiracial Activist, December 1, 2000

- Book Forum article

- Editorial Work, Greater Good Magazine, Summer 2008

- 1969 births

- Living people

- African-American feminists

- American feminists

- African-American women writers

- African-American Jews

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish women writers

- Bisexual feminists

- Bisexual women

- LGBT African Americans

- LGBT Jews

- African-American novelists

- American women novelists

- Bisexual writers

- LGBT people from Mississippi

- LGBT writers from the United States

- Jewish American novelists

- Jewish non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- American feminist writers

- Third-wave feminism

- Women memoirists

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- American memoirists

- People from the Bronx

- Writers from Jackson, Mississippi

- Writers from New York City

- Writers from the San Francisco Bay Area

- Yale University alumni

- Activists from New York (state)

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Novelists from Mississippi

- American women non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- BBC 100 Women