Ghana–Togo Mountain languages

| Ghana–Togo Mountain languages | |

|---|---|

| Togo Remnant, Central Togo | |

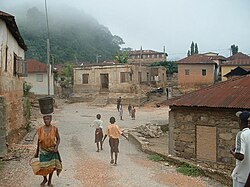

| Geographic distribution | Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Togo |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo?

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | kato1245 (Ka-Togo)nato1234 (Na-Togo) |

The Ghana–Togo Mountain languages, formerly called Togorestsprachen (Togo Remnant languages) and Central Togo languages, form a grouping of about fourteen languages spoken in the mountains of the Ghana–Togo borderland. They are part of the Kwa branch of the Niger–Congo family.

History of classification

Bernhard Struck, in 1912, was the first to group together these languages under the label Semibantu von Mitteltogo. Westermann, in his classification of the then Sudanic languages, adopted the grouping but called it Togorestsprachen.[1] This was mainly a loose geographical-typological grouping based on the elaborate noun class systems of the languages; lack of comparative data prevented a more definitive phylogenetic classification. Bernd Heine (1968) carried out comparative research among the group, establishing a basic division between Ka-Togo and Na-Togo based on the word for 'flesh' in the languages. Dakubu and Ford (1988) renamed this cluster the Central Togo languages, a term still used by some (e.g. Blench 2001); since the mid-90s, the term Ghana–Togo Mountain languages has become more common.

No comparative study of the languages has appeared in print since Heine (1968); Blench (unpublished) presented a tentative reclassification of the group in 2001, noting the internal diversity of the grouping. It is still unclear whether the grouping forms a branch on its own within Kwa.[2]

Features

A much noted characteristic of these languages is their typical Niger–Congo noun class system, since in many surrounding languages only remnants of such a system are found. All Ghana–Togo Mountain languages are tonal and most have a nine or ten vowel system employing ATR vowel harmony. Both Ewe and Twi, the dominant regional languages, have exerted considerable influence on many GTM languages.

Languages

| English names | Autonyms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| People | Language | ||

| Na | Adele | Bidire | Gidire |

| Anii, Basila | |||

| Giseme, Akpe | |||

| Logba | Akpanawò | Ikpana | |

| Lelemi, Buem | Lε-lεmi | ||

| Lefana, Buem | Lε-fana | ||

| Siwu-Lolobi, Akpafu | sg. Ɔwu, pl. Mawu |

Siwu | |

| Likpe | sg. Ɔkpεlá, pl. Bakpεlá |

Sεkpεlé | |

| Santrokofí | sg. Ɔlɛɛ, pl. Balɛɛ |

Sεlεε | |

| Ka | Avatime | Ke-dane-ma | Sì-yà |

| Nyangbo | Batrugbu | Tùtrùgbù | |

| Tafi | Bàgbɔ̀ | Tɛ̀gbɔ̀ | |

| Ikposo | Akpɔsɔ | Ikpɔsɔ | |

| Bowiri, Tora | Bawuli | Tuwuli | |

| Ahlon | Igo | ||

| Akebu | Ǝkpǝǝβǝ | Kɨkpǝǝkǝ | |

| Animere | Animere | ||

Classification of GTM languages

Heine (1968) placed the GTM languages into two branches of Kwa, Na-Togo and Ka-Togo:

- Na-Togo

- Ka-Togo

However, this classification was distorted by influence from Ewe on the one hand and Twi on the other. Blench (2006) makes the following tentative classification, which he expects to change as more data becomes available. One branch each of the Na and Ka languages are split off. As with Heine's classification, these may be independent branches of Kwa:

- Na-Togo (reduced)

- 1.

- Lelemi

- Siwu (Akpafu–Lolobi)

- Likpe

- Santrokofi

- 2. Logba

- 1.

- Anii–Adere

- Ka-Togo (reduced)

- 1.

- 2.

- Kebu–Animere

Ethnologue also lists Agotime, which they note is similar to Ahlo.

Westernmann (1922)[3] also includes Boro, but this is uncertain due to the little data that is available.

See also

- Boro language (Ghana), an extinct and scarcely attested language from the area that may be Na-Togo

- List of Proto-Central Togo reconstructions (Wiktionary)

Bibliography

- ^ E.g. Westermann 1935:146

- ^ Blench (2001) says that 'Although much of the literature and in particular Heine (1968) treats the Central Togo languages as a unit, since Stewart (1989) it has generally been accepted that these form distinct branches showing no particular relationship.'

- ^ Westermann, Diedrich Hermann (1922) 'Vier Sprachen aus Mitteltogo. Likpe, Bowili, Akpafu und Adele, nebst einigen Resten der Borosprache. Nach Aufnahmen von Emil Funke und Adam Mischlich bearbeitet'. Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen, 25, 1-59.

- Blench, Roger (2001). Comparative Central Togo: What have we learnt since Heine? (paper presented at the 32nd Annual Conference on African Linguistics and subsequently revised), 39p.

- Funke, E. (1920) ' Original-Texte aus den Klassensprachen in Mittel-Togo', Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, 10, 261-313.

- Heine, Bernd (1968) Die Verbreitung und Gliedering der Togorestsprachen (Kölner Beiträge zur Afrikanistik vol. 1). Köln: Druckerei Wienand.

- Kropp Dakubu, M.E. & K.C. Ford (1988) 'The Central Togo Languages'. In: The Languages of Ghana, M.E. Kropp-Dakubu (ed.), 119–153. London: Kegan Paul International.

- Plehn, Rudolf (1899) 'Beiträge zur Völkerkunde des Togo-Gebietes', in Mittheilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen, 2, part III, 87—124.

- Seidel, A., (1898) 'Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Sprachen in Togo. Aufgrund der von Dr. Rudolf Plehn und anderen gesammelten Materialien bearbeitet'. Zeitschrift für Afrikanische und Oceanische Sprachen, 4, 201-286

- Seidel treats Avatime (203-218), Logba (218-227), Nyangbo-Tafi (227-229), Nkunya (230-234), Bórada (235-238), Boviri (239-242), Akpafu (242-246), 'Santrokofi' (246-250), Likpe (250-254), Axolo (254-257), Akposo (257-264), Kebu (264-267), Atakpame (267-272), the Fetischsprachen Agu (273-274), Gbelle/Muatse (275-286), and the extinct Boro (286).

- Struck, Bernhard (1912) 'Einige Sudan-Wortstämme', Zeitschrift für Kolonialsprachen, 2/3, 2/4.

- Westermann, Diedrich Hermann (1935) 'Charakter und Einteilung der Sudansprachen', Africa, 8, 2, 129-148.