Naraka

Naraka (Sanskrit: नरक, literally of man) is the realm of hell in Indian religions. According to some schools of Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism, Naraka is a place of torment. The word Neraka (modification of Naraka) in Indonesian and Malaysian has also been used to describe the Islamic concept of Hell.[1]

Alternatively, the "hellish beings" that are said to reside in this underworld are often referred to as Narakas. These beings are also termed in Hindi as Narakis (Sanskrit: नारकीय, Nārakī), Narakarnavas (Sanskrit: नरकार्णव, Narakārṇava) and Narakavasis (Sanskrit: नरकवासी, Narakavāsī).

Hinduism

Naraka in Vedas, is a place where souls are sent for the expiation of their sins. It is mentioned especially in dharmaśāstras, itihāsas and Purāṇas but also in Vedic samhitas,[2][3] Aranyakas[4] and Upaniṣads.[5][6][7][8] Some Upanisads speak of 'darkness' instead of hell.[9] A summary of Upaniṣads, Bhagavad Gita, mentions hell several times.[10] Even Adi Sankara mentions it in his commentary on Vedanta sutra.[11] Except the views of Hindu philosopher Madhva, it is not seen as place of eternal damnation within Hinduism.[12] Still, some people like members of Arya Samaj don't accept the existence of Naraka or consider it metaphorical.[citation needed]

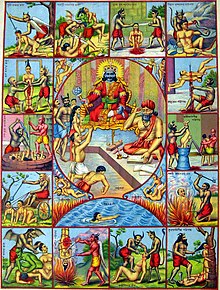

In Puranas like Bhagavata Purana, Garuda Purana and Vishnu Purana there are elaborate descriptions of many hells. They are situated above the Garbhodaka ocean.[13]

Yama, Lord of Justice, judges living beings after death and assigns appropriate punishments. Nitya-samsarins (forever transmigrating ones) can experience Naraka for expiation.[14] After the period of punishment is complete, they are reborn on earth[15] in human or bestial bodies.[16] Therefore, neither naraka nor svarga[17] are permanent abodes.

Yama Loka is the abode of Lord Yama. Yama is Dharmaraja or Dharma king; Yama Loka is a temporary purgatorium for sinners (papi). According to Hindu scriptures, Yama's divine assistant Lord Chitragupta maintains a record of the individual deeds of every living being in the world, and based on the complete audit of his deeds, dispatches the soul of the deceased either to Svarga (Heaven) or to the various Narakas according to the nature of their sins. The scriptures describe that even people who have done a majority of good deeds could come to Yama Loka for redemption from the small sins they have committed, and once the punishments have been served for those sins they could be sent for rebirth to earth or to heaven. In the epic of Mahabharata, even the Pandavas (who represent righteousness and virtuousness) spent a brief time in hell for their small sins.

At the time of death, sinful souls are vulnerable for capture by Yamadutas, servants of Yama (who comes personally only in special cases). Yama ordered his servants to leave Vaishnavas alone.[18][19] Sri Vaishnavas are taken by Vishnudutas to Vaikuntha and Gaudiya Vaishnavas to Goloka.[citation needed]

Buddhism

In Buddhism, Naraka refers to the worlds of greatest suffering. Buddhist texts describe a vast array of tortures and realms of torment in Naraka; an example is the Devadūta-sutta from the Pāli Canon. The descriptions vary from text to text and are not always consistent with each other. Though the term is often translated as "hell", unlike the Abrahamic hells, Naraka is not eternal, though when a timescale is given, it is suggested to be extraordinarily long. In this sense, it is similar to purgatory, but unlike both Abrahamic hell and purgatory, there is no divine force involved in determining a being's entry and exit to and from the realm and no soul is involved. Rather, the being is brought here—as is the case with all the other realms in the Buddhist cosmology—by natural law: the law of karma, and they remain until the negative karma that brought them there has been used up.

Jainism

In Jainism, Naraka is the name given to realm of existence in Jain cosmology having great suffering. The length of a being's stay in a Naraka is not eternal, though it is usually very long—measured in billions of years. A soul is born into a Naraka as a direct result of his or her previous karma (actions of body, speech and mind), and resides there for a finite length of time until his karma has achieved its full result. After his karma is used up, he may be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of an earlier karma that had not yet ripened. Jain texts mention that these hells are situated in the seven grounds at the lower part of the universe. The seven grounds are:

- Ratna prabha

- Sharkara prabha.

- Valuka prabha.

- Panka prabha.

- Dhuma prabha.

- Tamaha prabha.

- Mahatamaha prabha.

See also

- Shurangama Sutra - Volume 6, Chapter 5: The Twelve Categories of Living Beings

- List of numbers in Hindu scriptures

Notes

- ^ Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore: From Colonialism to Nationalism Palgrave Macmillan, 29 Nov 2012 ISBN 9781137012333 p. 195

- ^ Śukla Yajur Veda 30.5

- ^ Atharva Veda 12.4.36

- ^ Aitareya Āraṇyaka 2.3.2.4,5

- ^ Mahanārāyaṇa Upaniṣad 1.50

- ^ Praśna Upaniṣad 3

- ^ Nirālamba Upaniṣad 2, 17

- ^ Paramahaṃsa Upaniṣad 3

- ^ asuryā nāma te lokā andhena tamasāvṛtāḥ - Īśa Upaniṣad 3

- ^ 1.41, 1.43, 16.16, 16.21

- ^ Vedānta sūtra 4.3.14

- ^ Helmuth von Glasenapp: Der Hinduismus. Religion und Gesellschaft im heutigen Indien, Hildesheim 1978, p. 248.

- ^ Bhāgavata Purāṇa 5.26.5

- ^ Bhakti Schools of Vedanta, by Swami Tapasyananda

- ^ Bhāgavata Purāṇa 5.26.37

- ^ Garuḍa Purāṇa 2.10.88-89, 2.46.9-10,28

- ^ Bhagavad gītā 9.21

- ^ Bhāgavata Purāṇa 6.3

- ^ Nṛsiṃha Purāṇa 9.1-2

External links

- Definition at godrealized.com

- Wat Thawet Buddhist Learning Garden Feature Article