SMS König

SMS König at sea

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake | King William II of Württemberg |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | October 1911 |

| Launched | 1 March 1913 |

| Commissioned | 10 August 1914 |

| Fate | Scuttled 21 June 1919 in Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in) |

| Beam | 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS König[a] was the first of four Template:Sclass- dreadnought battleships of the Imperial German Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) during World War I. König (Template:Lang-en) was named in honor of King William II of Württemberg. Laid down in October 1911, the ship was launched on 1 March 1913. Final construction on König was completed shortly after the outbreak of World War I; she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 9 August 1914.

Along with her three sister ships, Grosser Kurfürst, Markgraf, and Kronprinz, König took part in most of the fleet actions during the war. As the leading ship in the German line on 31 May 1916 in the Battle of Jutland, König was heavily engaged by several British battleships and suffered ten large-caliber shell hits. In October 1917, she forced the Russian pre-dreadnought battleship Slava to scuttle herself in the Battle of Moon Sound, which followed Germany's successful Operation Albion.

König was interned, along with the majority of the High Seas Fleet, at Scapa Flow in November 1918 following the Armistice. On 21 June 1919, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter gave the order to scuttle the fleet, including König, while the British guard ships were out of the harbor on exercises. Unlike most of the scuttled ships, König was never raised for scrapping; the wreck is still on the bottom of the bay.

Design

The four Template:Sclass-s were ordered as part of the Anglo-German naval arms race; they were the fourth generation of German dreadnought battleships, and they were built in response to the British Template:Sclass- that had been ordered in 1909.[1] The Königs represented a development of the earlier Template:Sclass-, with the primary improvement being a more efficient arrangement of the main battery. The ships had also been intended to use a diesel engine on the center propeller shaft to increase their cruising range, but development of the diesels proved to be more complicated than expected, so an all-steam turbine powerplant was retained.[2]

König displaced 25,796 t (25,389 long tons) as built and 28,600 t (28,100 long tons) fully loaded, with a length of 175.4 m (575 ft 6 in), a beam of 29.5 m (96 ft 9 in) and a draft of 9.19 m (30 ft 2 in). She was powered by three Parsons steam turbines, with steam provided by three oil-fired and twelve coal-fired Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boilers, which developed a total of 42,708 shaft horsepower (31,847 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The ship had a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Her crew numbered 41 officers and 1,095 enlisted men.[3]

She was armed with ten 30.5 cm (12 in) SK L/50 guns arranged in five twin gun turrets:[b] two superfiring turrets each fore and aft and one turret amidships between the two funnels.[5] König was the first German battleship to mount all of her main battery artillery on the centerline. Like the earlier Kaiser-class battleships, König could bring all of her main guns to bear on either side, but the newer vessel enjoyed a wider arc of fire due to the all-centerline arrangement.[6] Her secondary armament consisted of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns and six 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 quick-firing guns, all mounted singly in casemates. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she was also armed with five 50 cm (20 in) underwater torpedo tubes, one in the bow and two on each beam.[5]

The ship's armored belt consisted of Krupp cemented steel that was 35 cm (13.8 in) thick in the central portion that protected the propulsion machinery spaces and the ammunition magazines, and was reduced to 18 cm (7.1 in) forward and 12 cm (4.7 in) aft. In the central portion of the ship, horizontal protection consisted of a 10 cm (3.9 in) deck, which was reduced to 4 cm (1.6 in) on the bow and stern. The main battery turrets had 30 cm (11.8 in) of armor plate on the sides and 11 cm (4.3 in) on the roofs, while the casemate guns had 15 cm (5.9 in) of armor protection. The sides of the forward conning tower were also 30 cm thick.[5]

Service

König was ordered under the provisional name "S" and built at the Kaiserliche Werft dockyards in Wilhelmshaven, under construction number 33.[3][c] Her keel was laid in October 1911 and she was launched on 1 March 1913 by the King's cousin, Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg.[7] Fitting-out work was completed by 9 August 1914, the day she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet.[5] Directly after commissioning, König conducted sea trials, which were completed by 23 November 1914.[8] Her crew consisted of 41 officers and 1,095 enlisted men.[5] Afterward, the ship was attached to V Division of III Battle Squadron of the German High Seas Fleet, where she would later be joined by her sister ships.[9] On 9 December, König ran aground in the Wilhelmshaven roadstead. Her sister ship Grosser Kurfürst, following right behind, rammed her stern and caused some minor damage. König was then freed from the bottom and taken back to Wilhelmshaven; repair work lasted until 2 January 1915.[8]

Operations in the North Sea

König took part in several fleet sorties in support of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers of I Scouting Group; however, due to her grounding outside Wilhelmshaven,[8] the ship missed the first operation of these battlecruisers on the night of 15/16 December 1914, when they were tasked with bombarding the English coast to lure out a portion of the British Grand Fleet to the waiting German fleet.[10] On 22 January 1915, König and the rest of III Squadron were detached from the fleet to conduct maneuver, gunnery, and torpedo training in the Baltic. They returned to the North Sea on 11 February, too late to assist I Scouting Group at the Battle of Dogger Bank.[8]

König then took part in several sorties into the North Sea. On 29 March, the ship led the fleet out to Terschelling. Three weeks later, on 17–18 April, she supported an operation in which the light cruisers of II Scouting Group laid mines off the Swarte Bank. Another fleet advance occurred on 22 April, again with König in the lead. On 23 April, III Squadron returned to the Baltic for another round of exercises lasting until 10 May. Another minelaying operation was conducted by II Scouting Group on 17 May, with the battleship again in support.[8]

König participated in a fleet advance into the North Sea which ended without combat from 29 until 31 May. She was then briefly assigned to picket duty in the German defensive belt. The ship again ran aground on 6 July, though damage was minimal. The ship supported a minelaying operation on 11–12 September off Texel. Another fleet advance followed on 23–24 October; after returning, König went into drydock for maintenance, rejoining the fleet by 4 November.[8] The ship was then sent back to the Baltic for more training on 5–20 December. On the return voyage, she was slightly damaged after grounding in the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal during a snow storm.[11] König was in the Baltic on 17 January 1916 for further training, then on 24 January returned to the North Sea. Two fleet advances followed on 5–6 March and 21–22 April.[12]

König was available on 24 April 1916 to support a raid on the English coast, again as support for the German battlecruiser force in I Scouting Group. The battlecruisers left the Jade Estuary at 10:55, and the rest of the High Seas Fleet followed at 13:40. The battlecruiser Seydlitz struck a mine while en route to the target, and had to withdraw.[13] The other battlecruisers bombarded the town of Lowestoft unopposed, but during the approach to Yarmouth, they encountered the British cruisers of the Harwich Force. A short artillery duel ensued before the Harwich Force withdrew. Reports of British submarines in the area prompted the retreat of I Scouting Group. At this point, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, who had been warned of the sortie of the Grand Fleet from its base at Scapa Flow, also withdrew to safer German waters.[14] König then went to the Baltic for another round of exercises, including torpedo drills off Mecklenburg.[12]

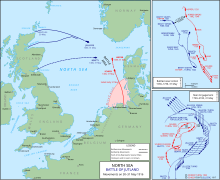

Battle of Jutland

König was present during the fleet operation that resulted in the battle of Jutland which took place on 31 May and 1 June 1916. The German fleet again sought to draw out and isolate a portion of the Grand Fleet and destroy it before the main British fleet could retaliate. König, followed by her sisters Grosser Kurfürst, Markgraf, and Kronprinz, made up V Division of III Battle Squadron, and they were the vanguard of the fleet. III Battle Squadron was the first of three battleship units; directly astern were the Kaiser-class battleships of VI Division, III Battle Squadron. Directly astern of the Kaiser-class ships were the Template:Sclass- and Template:Sclass-es of I Battle Squadron; in the rear guard were the obsolescent Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron.[9]

Shortly before 16:00 CET,[d] the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group encountered the British 1st Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of David Beatty. The opposing ships began an artillery duel that saw the destruction of Indefatigable, shortly after 17:00,[15] and Queen Mary, less than half an hour later.[16] By this time, the German battlecruisers were steaming south to draw the British ships toward the main body of the High Seas Fleet. At 17:30, König's crew spotted both I Scouting Group and the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron approaching. The German battlecruisers were steaming to starboard, while the British ships steamed to port. At 17:45, Scheer ordered a two-point turn to port to bring his ships closer to the British battlecruisers, and a minute later at 17:46, the order to open fire was given.[17][e]

König, Grosser Kurfürst, and Markgraf were the first to reach effective gunnery range; they engaged the battlecruisers Lion, Princess Royal, and Tiger, respectively, at a range of 21,000 yards.[18] König's first salvos fell short of her target, and so she shifted her fire to the nearer Tiger. Simultaneously, König and her sisters began firing on the destroyers Nestor and Nicator with their secondary battery.[19] The two destroyers closed in on the German line, and after having endured a hail of gunfire, maneuvered into a good firing position. Each ship launched two torpedoes apiece at König and Grosser Kurfürst, although all four weapons missed. In return, a secondary battery shell from one of the battleships hit Nestor and wrecked her engine room. The ship, along with the destroyer Nomad, was crippled and lying directly in the path of the advancing German line. Both of the destroyers were sunk, and German torpedo boats stopped to pick up survivors.[20] At around 18:00, König and her three sister ships shifted their fire to the approaching Template:Sclass-s of 5th Battle Squadron. König initially engaged Barham until that ship was out of range, then shifted to Valiant. However, the faster British battleships were able to move out of effective gunnery range quickly.[21]

Shortly after 19:00, the German cruiser Wiesbaden had become disabled by a shell from the British battlecruiser Invincible; Rear Admiral Paul Behncke in König attempted to maneuver his four ships to cover the stricken cruiser.[22] Simultaneously, the British III and IV Light Cruiser Squadrons began a torpedo attack on the German line; while advancing to torpedo range, they smothered Wiesbaden with fire from their main guns. König and her sisters fired heavily on the British cruisers, but even sustained fire from the battleships' main guns failed to drive off the British cruisers.[23] In the ensuing melee, the British armored cruiser Defence was struck by several heavy caliber shells from the German dreadnoughts. One salvo penetrated the ship's ammunition magazines and, in a massive explosion, destroyed the cruiser.[24]

Shortly after 19:20, König again entered gunnery range of the battleship Warspite and opened fire on her target. She was joined by the dreadnoughts Friedrich der Grosse, Ostfriesland, Helgoland, and Thüringen. However, König rapidly lost sight of Warspite, as she had been in the process of turning east-northeast.[25] Nearly simultaneously, British light cruisers and destroyers attempted to make a torpedo attack against the leading ships of the German line, including König. Shortly thereafter, the main British line came into range of the German fleet; at 19:30 the British battleships opened fire on both the German battlecruiser force and the König-class ships. König came under especially heavy fire during this period. In the span of 5 minutes, Iron Duke fired 9 salvos at König from a range of 12,000 yards; only one shell hit the ship. The 13.5-inch shell struck the forward conning tower but instead of penetrating, the shell ricocheted off and detonated some 50 yards past the ship. Rear Admiral Behncke was injured, though he remained in command of the ship. The ship was then obscured by smoke that granted a temporary reprieve.[26]

By 20:00, the German line was ordered to turn westward to disengage from the British fleet. König, at the head, completed her turn and then reduced speed to allow the vessels behind her to return to formation. Shortly thereafter, four British light cruisers resumed the attacks on the crippled Wiesbaden; the leading German battleships, including König, opened fire on the cruisers in an attempt to drive them off.[27] The pursuing British battleships had by this time turned further south and nearly managed to "cross the T" of the German line. To rectify this situation, Admiral Scheer ordered a 16-point turn south and sent Hipper's battlecruisers on a charge toward the British fleet.[28] During the turn, König was struck by a 13.5-inch shell from Iron Duke; the shell hit the ship just aft of the rearmost gun turret. König suffered significant structural damage, and several rooms were filled with smoke. During the turn to starboard, Vice Admiral Schmidt, the commander of I Battle Squadron, decided to turn his ships immediately, instead of following the leading ships in succession. This caused a great deal of confusion, and nearly resulted in several collisions. As a result, many of the German battleships were forced to drastically reduce speed, which put the entire fleet in great danger.[29] In an attempt to mitigate the predicament, König turned to port and laid a smokescreen between the German and British lines.[30]

During the battle, König suffered significant damage. A heavy shell penetrated the main armored deck toward the bow. Another shell hit the armored bulkhead at the corner and shoved it back five feet, breaking off a large piece from the armor plate in the process. Shell splinters from another hit penetrated several of the casemates that held the 15 cm secondary guns, two of which were disabled. The ammunition stores for these two guns were set on fire and the magazines had to be flooded to prevent an explosion. The ship nevertheless remained combat effective, as her primary battery remained in operation, as did most of her secondary guns; König could also steam at close to her maximum speed. Other areas of the ship had to be counter-flooded to maintain stability; 1,600 tons of water entered the ship, either as a result of battle damage or counter-flooding efforts.[31][32] The flooding rendered the battleship sufficiently low in the water to prevent the ship from being able to cross the Amrum Bank until 09:30 on 1 June.[33] König was taken to Kiel for initial repairs, as that was the only location that had a floating dry dock large enough to fit the ship. Repairs were conducted there from 4 to 18 June, at which point the ship was transferred to the Howaldtswerke shipyard. König was again ready to join the fleet by 21 July.[34] In the course of the battle, she suffered 45 men killed and 27 wounded, the highest tally for any surviving battleship in the German fleet.[35]

Subsequent operations

Following completion of repairs, König was again detached to the Baltic for training, from the end of July until early August. König was back in the North Sea on 5 August. A major fleet sortie occurred on 18–20 August, with König again in the lead.[12] I Scouting Group was to bombard the coastal town of Sunderland, in an attempt to draw out and destroy Beatty's battlecruisers. However, as Von der Tann and Moltke were the only battlecruisers in fighting condition, the new battleship Bayern and two of König's sisters, Markgraf and Grosser Kurfürst, were temporarily assigned to I Scouting Group. Admiral Scheer and the rest of the High Seas Fleet would trail behind providing cover.[36] The British were aware of the German plans and sortied the Grand Fleet to meet them, leading to the inconclusive action of 19 August 1916. By 14:35, Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and, unwilling to engage the whole of the Grand Fleet just 11 weeks after the decidedly close call at Jutland, turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[37]

König remained in port until 21 October, when the ship was again sent to the Baltic for training. The ship returned to the fleet on 3 November. König and the rest of III Squadron then steamed out to Horns Reef on 5–6 November. König was then assigned various tasks, including guard duty in the German Bight and convoy escort in the Baltic. 1917 saw several training missions in the Baltic during 22 February – 4 March; 14–22 March and 17 May – 9 June. König then went into Wilhelmshaven for maintenance on 16 June. The installation of a new heavy foremast and other work lasted until 21 July. On 10 September, König again went into the Baltic for training maneuvers.[12]

Operation Albion

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German navy decided to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga. The Admiralstab (the Navy High Command) planned an operation to seize the Baltic island of Ösel, and specifically the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula.[38] On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands; the primary naval component was to comprise the flagship, Moltke, along with III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet. V Division included the four König-class ships, and was by this time augmented with the new battleship Bayern. VI Division consisted of the five Kaiser-class battleships. Along with 9 light cruisers, 3 torpedo boat flotillas, and dozens of mine warfare ships, the entire force numbered some 300 ships, supported by over 100 aircraft and 6 zeppelins. The invasion force amounted to approximately 24,600 officers and enlisted men.[39] Opposing the Germans were the old Russian pre-dreadnoughts Slava and Tsesarevich, the armored cruisers Bayan, Admiral Makarov, and Diana, 26 destroyers, and several torpedo boats and gunboats. The garrison on Ösel numbered some 14,000 men.[40]

König departed Kiel on 23 September for Putziger Wiek, where the ship remained until 10 October.[12] The operation began on 12 October; at 03:00 König anchored off Ösel in Tagga Bay and disembarked soldiers. By 05:50, König opened fire on Russian coastal artillery emplacements,[41] joined by Moltke, Bayern, and the other three König-class ships. Simultaneously, the Kaiser-class ships engaged the batteries on the Sworbe peninsula; the objective was to secure the channel between Moon and Dagö islands, which would block the only escape route of the Russian ships in the Gulf. Both Grosser Kurfürst and Bayern struck mines while maneuvering into their bombardment positions, with minimal damage to the former. Bayern was severely wounded, and had to be withdrawn to Kiel for repairs.[40] At 17:30, König departed the area to refuel; she returned to the Irben Strait on 15 October.[41]

On 16 October, it was decided to detach a portion of the invasion flotilla to clear the Russian naval forces in Moon Sound; these included the two Russian pre-dreadnoughts. To this end, König and Kronprinz, along with the cruisers Strassburg and Kolberg and a number of smaller vessels, were sent to engage the Russian battleships, leading to the Battle of Moon Sound. They arrived by the morning of 17 October, but a deep Russian minefield thwarted their progress. The Germans were surprised to discover that the 30.5 cm guns of the Russian battleships out-ranged their own 30.5 cm guns.[f] The Russian ships managed to keep the distance wide enough to prevent the German battleships from being able to return fire, while still firing effectively on the German ships, and the Germans had to take several evasive maneuvers to avoid the Russian shells. However, by 10:00, the minesweepers had cleared a path through the minefield, and König and Kronprinz dashed into the bay. By 10:13, König was in range of Slava and quickly opened fire. Meanwhile, Kronprinz fired on both Slava and the cruiser Bayan. The Russian vessels were hit dozens of times, until at 10:30 the Russian naval commander, Admiral Bakhirev, ordered their withdrawal.[42] König had hit Slava seven times; the damage inflicted prevented her from escaping to the north.[41] Instead, she was scuttled and her crew was evacuated on a destroyer.[42] In the course of the engagement, König struck the cruiser Bayan once. Following the engagement, König fired on shore batteries on Woi and Werder.[41]

On 20 October, König was towed by mine sweepers into the Kuiwast roadstead.[43] König transferred soldiers to the island of Schildaum which was then occupied.[41] By that time, the fighting on the islands was winding down; Moon, Ösel, and Dagö were in German possession. The previous day, the Admiralstab had ordered the cessation of naval actions and the return of the dreadnoughts to the High Seas Fleet as soon as possible.[43] On the return voyage, König struck bottom in a heavy swell. The ship was repaired in Kiel; the work lasted until 17 November.[41]

Final operations

Following König's return from the Baltic, the ship was tasked with guard duties in the North Sea and with providing support for minesweepers. König returned to the Baltic on 22 December for further training, which lasted until 8 January 1918. Another round of exercises was conducted from 23 February to 11 March. On 20 April König steamed out to assist a German patrol that was engaged with British forces. The ship was part of the force that steamed to Norway to intercept a heavily escorted British convoy on 23–25 April, though the operation was canceled when the battlecruiser Moltke suffered mechanical damage. König was briefly grounded in the northern harbor of the island of Helgoland on 30 May. Two months later, on 31 July, König and the rest of III Squadron covered a minesweeping unit in the North Sea. The ship then went to the Baltic for training on 7–18 August, after which König returned to the North Sea. König conducted her last exercise in the Baltic starting on 28 September; the maneuvers lasted until 1 October.[41]

König was to have taken part in a final fleet action days before the Armistice, an operation which envisioned the bulk of the High Seas Fleet sortieing from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet. To retain a better bargaining position for Germany, Admirals Hipper and Scheer intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, whatever the cost to the fleet.[44] On 29 October 1918, the order was given to depart from Wilhelmshaven to consolidate the fleet in the Jade roadstead, with the intention of departing the following morning. However, starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen mutinied.[45] The unrest spread to other battleships, including König.[41] The operation was ultimately canceled; in an attempt to suppress the mutiny, Admiral Scheer ordered the fleet be dispersed.[46] König and the rest of III Squadron were sent to Kiel. During the subsequent mutiny, König's captain was wounded three times, and both her first officer and adjutant were killed.[41]

Fate

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base at Scapa Flow.[46] Prior to the departure of the German fleet, Admiral Adolf von Trotha made clear to von Reuter that he could not allow the Allies to seize the ships, under any conditions.[47] The fleet rendezvoused with the British light cruiser Cardiff, which led the ships to the Allied fleet that was to escort the Germans to Scapa Flow. The massive flotilla consisted of some 370 British, American, and French warships.[48] Once the ships were interned, their guns were disabled through the removal of their breech blocks.[49]

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Versailles Treaty. Von Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.[47] König sank at 14:00; the ship was never raised for scrapping, unlike most of the other capital ships that were scuttled. The rights to future salvage operations on the wreck were sold to Britain in 1962.[5]

The ship is now a popular dive site in Scapa Flow, lying at a depth of 40 m (130 ft) on a sandy floor to the east of Cava. She turned over as she sank and the hull faces upwards at about 20 m (66 ft) down. There are several dynamited holes in her superstructure where salvagers have gained access to obtain non-ferrous metals.[50] In 2017, marine archaeologists from the Orkney Research Center for Archaeology conducted extensive surveys of König and nine other wrecks in the area, including six other German and three British warships. The archaeologists mapped the wrecks with sonar and examined them with remotely operated underwater vehicles as part of an effort to determine how the wrecks are deteriorating.[51]

The wreck at some point came into the ownership of the firm Scapa Flow Salvage, which sold the rights to the vessel to Tommy Clark, a diving contractor, in 1981. Clark listed the wreck for sale on eBay with a "buy-it-now" price of £250,000, with the auction lasting until 28 June 2019. Three other wrecks—those of Kronprinz Wilhelm, Markgraf, and the light cruiser Karlsruhe—all also owned by Clark, were also placed for sale.[52] The wrecks of König and her two sisters ultimately sold for £25,500 apiece to a company from the Middle East, while Karlsruhe sold to a private buyer for £8,500.[53]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (Template:Lang-en).

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick loading, while the L/50 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/50 gun is 50 calibers, meaning that the gun is 45 times as long as it is in bore diameter.[4]

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)". See: Gröner, p. 27.

- ^ The times mentioned in this section are in CET, which is congruent with the German perspective. This is one hour ahead of UTC, the time zone commonly used in British works.

- ^ The compass can be divided into 32 points, each corresponding to 11.25 degrees. A two-point turn to port would alter the ships' course by 22.5 degrees.

- ^ The Russian ships had had their main battery turrets modified to allow elevation of the guns to 30°. This was much greater than the elevation of the German guns. See: Halpern, p. 218.

Citations

- ^ Herwig, p. 70.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 27.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f Gröner, p. 28.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 147.

- ^ Rüger, p. 147-148.

- ^ a b c d e f Staff, p. 29.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 286.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Staff, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e Staff, p. 30.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 53.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 54.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 110.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 111.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 114.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 116.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 137.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 138.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 140.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 145.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 169.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 173.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 175.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 177.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Campbell, p. 190.

- ^ Halpern, p. 327.

- ^ Campbell, p. 336.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 298.

- ^ Massie, p. 682.

- ^ Massie, p. 683.

- ^ Halpern, p. 213.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b Halpern, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Staff, p. 31.

- ^ a b Halpern, p. 218.

- ^ a b Halpern, p. 219.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- ^ a b Tarrant, p. 282.

- ^ a b Herwig, p. 256.

- ^ Herwig, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Herwig, p. 255.

- ^ MacDonald, pp. 73–75.

- ^ Gannon.

- ^ "Scapa Flow: Sunken WW1 battleships up for sale on eBay". BBC News. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Sunken WW1 Scapa Flow warships sold for £85,000 on eBay". BBC News. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Gannon, Megan (4 August 2017). "Archaeologists Map Famed Shipwrecks and War Graves in Scotland". Livescience.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- MacDonald, Rod (1998). Dive Scapa Flow. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 978-1-85158-983-8.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Rüger, Jan (2007). The Great Naval Game: Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521875769.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 2: Kaiser, König And Bayern Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-468-8.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

External links

![]() Media related to SMS König (ship, 1913) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to SMS König (ship, 1913) at Wikimedia Commons