Osteopenia

| Osteopenia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | low bone mass, low bone density |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, Endocrinology |

| Complications | development into osteoporosis |

Osteopenia, preferably known as "low bone mass" or "low bone density", is a condition in which bone mineral density is low. Because their bones are weaker, people with osteopenia may have a higher risk of fractures, and some people may go on to develop osteoporosis.[1] In 2010, 43 million older adults in the US had osteopenia.[2]

There is no single cause for osteopenia, although there are several risk factors, including modifiable (behavioral, including dietary and use of certain drugs) and non-modifiable (for instance, loss of bone mass with age). For people with risk factors, screening via a DXA scanner may help to detect the development and progression of low bone density. Prevention of low bone density may begin early in life and includes a healthy diet and weight-bearing exercise, as well as avoidance of tobacco and alcohol. The treatment of osteopenia is controversial: non-pharmaceutical treatment involves preserving existing bone mass via healthy behaviors (dietary modification, weight-bearing exercise, avoidance or cessation of smoking or heavy alcohol use). Pharmaceutical treatment for osteopenia, including bisphosphonates and other medications, may be considered in certain cases but is not without risks. Overall, treatment decisions should be guided by considering each patient's constellation of risk factors for fractures.

Risk factors

Many divide risk factors for osteopenia into fixed (non-changeable) and modifiable factors. Osteopenia can also be secondary to other diseases. An incomplete list of risk factors:[3][4][5]

Fixed

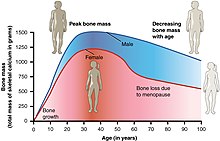

- Age: bone density peaks at age 35, and then decreases. Bone density loss occurs in both men and women[6]

- Race: Caucasian and Asian people have increased risk

- Sex: women are at higher risk, particularly those with early menopause

- Family history: low bone mass in the family increases risk

Modifiable / behavioral

- Tobacco use

- Alcohol use

- Inactivity – particularly lack of weight-bearing or resistance activities [7][8][9]

- Insufficient caloric intake - osteopenia can be connected to female athlete triad syndrome, which occurs in female athletes as a combination of energy deficiency, menstrual irregularities, and low bone mineral density.[10]

- Low nutrient diet (particularly calcium, Vitamin D)

Other diseases

- Celiac disease, via poor absorption of calcium and vitamin D[11][12]

- Hyperthyroidism

- Anorexia nervosa[13]

Medications

- Steroids

- Anticonvulsants

Screening and diagnosis

The ISCD (International Society for Clinical Densitometry) and the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommend that older adults (women over 65 and men over 70) and adults with risk factors for low bone mass, or previous fragility fractures, undergo DXA testing.[14] The DXA (dual X-ray absorptiometry) scan uses a form of X-ray technology, and offers accurate bone mineral density results with low radiation exposure.[15][16]

The United States Preventive Task Force recommends osteoporosis screening for women with increased risk over 65 and states there is insufficient evidence to support screening men.[17] The main purpose of screening is to prevent fractures. Of note, USPSTF screening guidelines are for osteoporosis, not specifically osteopenia.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends use of central (hip and spine) DXA testing for accurate measure of bone density, emphasizing that peripheral or "screening" scanners should not be used to make clinically meaningful diagnoses, and that peripheral and central DXA scans cannot be compared to each other.[18]

DXA scanners can be used to diagnose osteopenia or osteoporosis as well as to measure bone density over time as people age or undergo medical treatment or lifestyle changes.

Information from the DXA scanner creates a bone mineral density T-score by comparing a patient's density to the bone density of a healthy young person. Bone density between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations below the reference, or a T-score between −1.0 and −2.5, indicates osteopenia (a T-score greater than or equal to −2.5 indicates osteoporosis). Calculation of the T-score itself may not be standardized. The ISCD recommends using Caucasian women between 20 and 29 years old as the baseline for bone density for ALL patients, but not all facilities follow this recommendation.[19][20][21][14]

The ISCD recommends that Z-scores, not T-scores, be used to classify bone density in premenopausal women and men under 50.[22]

Prevention

Prevention of low bone density can start early in life by maximizing peak bone density. Once a person loses bone density, the loss is usually irreversible, so preventing (greater than normal) bone loss is important.[23]

Actions to maximize bone density and stabilize loss include:[24][25][26][27]

- Exercise, particularly weight-bearing exercise and resistance exercises

- Adequate caloric intake

- Sufficient calcium in diet: older adults may have increased calcium needs—of note, medical conditions such as Celiac and hyperthyroidism can affect absorption of calcium[25]

- Sufficient Vitamin D in diet

- Estrogen replacement

- Avoidance of steroid medications

- Limit alcohol use and smoking

Pharmaceutical treatment

The pharmaceutical treatment of osteopenia is controversial and more nuanced than well-supported recommendations for improved nutrition and weight-bearing exercise.[28][29][5] The diagnosis of osteopenia in and of itself does not always warrant pharmaceutical treatment.[30][31] Many people with osteopenia may be advised to follow risk prevention measures (as above).

Risk of fracture guides clinical treatment decisions: the World Health Organization (WHO) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) estimates the probability of hip fracture and the probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF), which could occur in a bone other than the hip.[32][33] In addition to bone density (T-score), calculation of the FRAX score involves age, body characteristics, health behaviors, and other medical history.[34]

As of 2014, The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends pharmaceutical treatment for osteopenic postmenopausal women and men over 50 with FRAX hip fracture probability of >3% or FRAX MOF probability >20%.[35] As of 2016, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology agree.[36] In 2017, the American College of Physicians recommended that clinicians use individual judgment and knowledge of patients' particular risk factors for fractures, as well as patient preferences, to decide whether to pursue pharmaceutical treatment for women with osteopenia over 65.[37]

Pharmaceutical treatment for low bone density includes a range of medications. Commonly used drugs include bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, and ibandronate) - some studies show that decreased fracture risk and increased bone density after bisphosphonate treatment for osteopenia.[38] Other medications include selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (raloxifene; estrogen; calcitonin; and teriparatide).[39]

These drugs are not without risks.[40][41] In this complex landscape, many argue that clinicians must consider a patient's individual risk of fracture, not simply treat those with osteopenia as equally at risk. A 2005 editorial in the Annals of Internal Medicine states "The objective of using osteoporosis drugs is to prevent fractures. This can be accomplished only by treating patients who are likely to have a fracture, not by simply treating T-scores."[42]

History

Osteopenia, from Greek ὀστέον (ostéon), "bone" and πενία (penía), "poverty", is a condition of sub-normally mineralized bone, usually the result of a rate of bone lysis that exceeds the rate of bone matrix synthesis. See also osteoporosis.

In June 1992, the World Health Organization defined osteopenia.[43][29] An osteoporosis epidemiologist at the Mayo Clinic who participated in setting the criterion in 1992 said "It was just meant to indicate the emergence of a problem", and noted that "It didn't have any particular diagnostic or therapeutic significance. It was just meant to show a huge group who looked like they might be at risk."[44]

See also

References

- ^ Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF, Josse RG, Leslie WD (September 2007). "Low bone mineral density and fracture burden in postmenopausal women". CMAJ. 177 (6): 575–80. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070234. PMC 1963365. PMID 17846439.

- ^ Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (November 2014). "The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 29 (11): 2520–6. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2269. PMC 4757905. PMID 24771492.

- ^ staff, familydoctor org editorial. "What Is Osteopenia? – Osteoporosis". familydoctor.org. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Who's at risk? | International Osteoporosis Foundation". www.iofbonehealth.org. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ a b Karaguzel, Gulay; Holick, Michael F. (December 2010). "Diagnosis and treatment of osteopenia". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 11 (4): 237–251. doi:10.1007/s11154-010-9154-0. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 21234807. S2CID 13519685.

- ^ Demontiero O, Vidal C, Duque G (April 2012). "Aging and bone loss: new insights for the clinician". Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 4 (2): 61–76. doi:10.1177/1759720X11430858. PMC 3383520. PMID 22870496.

- ^ Duncan CS, Blimkie CJ, Cowell CT, Burke ST, Briody JN, Howman-Giles R (February 2002). "Bone mineral density in adolescent female athletes: relationship to exercise type and muscle strength". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 34 (2): 286–94. doi:10.1097/00005768-200202000-00017. PMID 11828239.

- ^ Kohrt WM, Bloomfield SA, Little KD, Nelson ME, Yingling VR (November 2004). "American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: physical activity and bone health". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 36 (11): 1985–96. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000142662.21767.58. PMID 15514517.

- ^ Rector RS, Rogers R, Ruebel M, Hinton PS (February 2008). "Participation in road cycling vs running is associated with lower bone mineral density in men". Metabolism. 57 (2): 226–32. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2007.09.005. PMID 18191053.

- ^ Papanek PE (October 2003). "The female athlete triad: an emerging role for physical therapy". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 33 (10): 594–614. doi:10.2519/jospt.2003.33.10.594. PMID 14620789.

- ^ Mazure R, Vazquez H, Gonzalez D, Mautalen C, Pedreira S, Boerr L, Bai JC (December 1994). "Bone mineral affection in asymptomatic adult patients with celiac disease". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 89 (12): 2130–4. PMID 7977227.

- ^ Micic D, Rao VL, Semrad CE (July 2019). "Celiac Disease and Its Role in the Development of Metabolic Bone Disease". Journal of Clinical Densitometry. 23 (2): 190–199. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2019.06.005. PMID 31320223.

- ^ "Anorexia Nervosa and Its Impact on Bone Health". Eating Disorders Catalogue. 2018-02-28. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ a b "2019 ISCD Official Positions – Adult – International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD)". Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Mazess R, Chesnut CH, McClung M, Genant H (July 1992). "Enhanced precision with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry". Calcified Tissue International. 51 (1): 14–7. doi:10.1007/bf00296209. PMID 1393769.

- ^ Njeh CF, Fuerst T, Hans D, Blake GM, Genant HK (January 1999). "Radiation exposure in bone mineral density assessment". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 50 (1): 215–36. doi:10.1016/s0969-8043(98)00026-8. PMID 10028639.

- ^ "Final Update Summary: Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: Screening – US Preventive Services Task Force". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Bone Density Test, Osteoporosis Screening & T-score Interpretation". National Osteoporosis Foundation. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ WHO Scientific Group on the Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis (2000 : Geneva, Switzerland) (2003). "Prevention and management of osteoporosis" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fracture Risk Assessment Tool". World Health Organization.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "2019 ISCD Official Positions – Adult – International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD)". Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Menopause & Osteoporosis". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ a b "Osteoporosis Overview | NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center". www.bones.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Preventing Osteoporosis". International Osteoporosis Foundation. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ "Diseases and Conditions Osteoporosis". www.rheumatology.org. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ Murphy, Kate (2009-09-07). "New Osteoporosis Diagnostic Tool Draws Criticism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- ^ a b "How A Bone Disease Grew To Fit The Prescription". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "One Minute Consult | What is osteopenia, and what should be done about it?". www.clevelandclinicmeded.com. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "Osteopenia Warrants Treatment—Selectively—to Reduce Fracture Risk". EndocrineWeb. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "FRAX — WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Unnanuntana, Aasis; Gladnick, Brian P; Donnelly, Eve; Lane, Joseph M (March 2010). "The Assessment of Fracture Risk". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 92 (3): 743–753. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00919. ISSN 0021-9355. PMC 2827823. PMID 20194335.

- ^ "Fracture Risk Assessment Tool". www.sheffield.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Cosman, F.; de Beur, S. J.; LeBoff, M. S.; Lewiecki, E. M.; Tanner, B.; Randall, S.; Lindsay, R. (October 2014). "Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis". Osteoporosis International. 25 (10): 2359–2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. ISSN 0937-941X. PMC 4176573. PMID 25182228.

- ^ Camacho, Pauline M.; Petak, Steven M.; Binkley, Neil; Clarke, Bart L.; Harris, Steven T.; Hurley, Daniel L.; Kleerekoper, Michael; Lewiecki, E. Michael; Miller, Paul D.; Narula, Harmeet S.; Pessah-Pollack, Rachel (September 2016). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis — 2016--Executive Summary". Endocrine Practice. 22 (9): 1111–1118. doi:10.4158/EP161435.ESGL. ISSN 1530-891X. PMID 27643923.

- ^ Qaseem, Amir; Forciea, Mary Ann; McLean, Robert M.; Denberg, Thomas D.; for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians (2017-06-06). "Treatment of Low Bone Density or Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures in Men and Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (11): 818–839. doi:10.7326/M15-1361. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 28492856.

- ^ Iqbal, Shumaila M; Qamar, Iqra; Zhi, Cassandra; Nida, Anum; Aslam, Hafiz M (2019-02-27). "Role of Bisphosphonate Therapy in Patients with Osteopenia: A Systemic Review". Cureus. 11 (2): e4146. doi:10.7759/cureus.4146. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 6488345. PMID 31058029.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rosen CJ (August 2005). "Clinical practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (6): 595–603. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp043801. PMID 16093468.

- ^ Staff, Editorial (2018-01-30). "Rethinking Drug Treatment for Osteopenia". Health and Wellness Alerts. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Alonso-Coello P, García-Franco AL, Guyatt G, Moynihan R (January 2008). "Drugs for pre-osteoporosis: prevention or disease mongering?". BMJ. 336 (7636): 126–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39435.656250.AD. PMC 2206291. PMID 18202066.

- ^ McClung, Michael R. (2005-05-03). "Osteopenia: To Treat or Not To Treat?". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (9): 796–7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00018. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 15867413. S2CID 40992917.

- ^ says, Albino Llaza (2010-04-12). "What is Osteopenia?". News-Medical.net. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Kolata, Gina (September 28, 2003). "Bone Diagnosis Gives New Data But No Answers". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)