Yalo

Yalo

يالو Yalu | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Etymology: from personal name, or "Place of the fallow deer"[1] | |

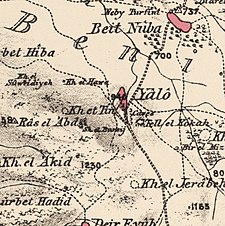

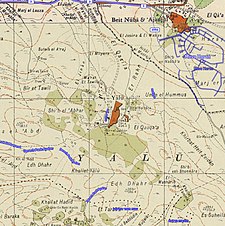

A series of historical maps of the area around Yalo (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°50′31″N 35°01′24″E / 31.84194°N 35.02333°E | |

| Palestine grid | 152/138 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Ramle |

| Date of depopulation | 7 June 1967 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14,992 dunams (14.992 km2 or 5.788 sq mi) |

| Population (1961) | |

| • Total | 1,644 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Expulsion by Israeli forces |

| Current Localities | Canada Park |

Yalo (Template:Lang-ar, also transliterated Yalu) was a Palestinian Arab village located 13 kilometres southeast of Ramla.[2] Identified by Edward Robinson as the ancient Canaanite and Israelite city of Aijalon,[2][3] in the Middle Ages it was the site of a Crusader castle, Castrum Arnaldi. After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Jordan formally annexed Yalo along with the rest of the West Bank.[4] Yalo's population increased dramatically owing to an influx of Palestinian refugees from neighbouring towns and villages depopulated during the 1948 war.

During the 1967 war, all the inhabitants of Yalo were expelled by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the village was destroyed, and Yalo and the entirety of Latrun were annexed from Jordan by Israel.[5][6] Subsequently, with donations from Canadian benefactors, the Jewish National Fund built a recreational space, Canada Park, which contains the former sites of Yalo and two other neighbouring villages, Dayr Ayyub,[7] and Imwas.[8]

History

Crusader period

The area was under contention in the Middle Ages by Christian and Muslim forces. In the Crusader period, there was a castle here called Castellum Arnaldi or Chastel Arnoul.[9] It was destroyed by Muslims in 1106, rebuilt in 1132–3, controlled by the Templars by 1179[10] and taken by Saladin in 1187.[9] Some of its ruins are still visible.[9]

Ottoman period

The village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, and in 1596 it appeared in the tax registers in the Nahiya of Ramlah of the Liwa of Gazza. It had a population of 38 households, all Muslim. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 33,3% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, summer crops, olive-trees, goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 4,500 Akçe.[11]

During his travels in Palestine in 1838, American Biblical scholar Edward Robinson studied Yalo, associating it with Aijalon, an ancient village mentioned in the Old Testament. Robinson relied upon the works of Jerome and Eusebius, who describe Aijalon as two Roman miles from Nicopolis; the descriptions of Aijalon in the Old Testament; and the philological similarities between the present-day Arabic name and its Canaanite root.[3]

In Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and Adjacent Regions (1856), Edward Robinson and Eli Smith situate Yalo between two ravines, overlooking "the beautiful meadow-like tract of Merj Ibn 'Omeir." They note that a fountain from the western ravine served as a water source for the village, that the place has "an old appearance", and that on the cliff beyond the eastern ravine lay a series of large caverns. In these first-hand descriptions garnered from their regional travels, they wrote,

"The village belongs to the family of the Sheikhs Abu Ghaush, who reside at Kuriet al-'Enab. One of the younger of them was now here, and paid us a visit in our tent. The people of Yâlo were well disposed, and treated us respectfully."[12]

Victor Guérin visited in 1863,[13] while an Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that Jalo had a population of 250, in 67 houses, though the population count included men, only.[14][15]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Yalo as "a small village on the slope of a low spur, with an open valley or small plain to the north. There is a spring to the east, where a branch valley runs down north, and on the east side of this valley are caves. The village stands 250 feet above the northern basin."[16]

British Mandate

According to the British Mandate's 1922 census of Palestine, Yalu had 811 inhabitants, all Muslims.[17] increasing in the 1931 census to 963, still all Muslims, living in a total of 245 houses.[18]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Yalo was 1,220 Muslims,[19] having a total of 14,992 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[20] Of this, 447 dunams of land was for plantations and irrigable land; 6,047 for cereals,[21] while 74 dunams were built-up land.[22]

1948 war

In the lead-up to the outbreak of 1948 Arab-Israeli war, on the night of 27 December 1947, the Etzioni Brigade of the Hagana blew up three houses in Yalo. This action formed part of a series what Israeli historian Benny Morris has described as "Haganah retaliatory strikes", the operational orders of which "almost invariably contained an order to blow up one or several houses (as well as to kill 'adult males' or 'armed irregulars')."[23]

-

Yalo 1943 1:20,000 (top left quadrant)

-

Yalo 1945 1:250,000

-

Yalo and the 1949 Armistice lines

Jordanian period

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Yalo was under Jordanian rule from 1948 until 1967.

On 2 November 1950 Palestinian children were targeted by the IDF when three of them children were shot, two fatally, by IDF troops near Dayr Ayyub in the Latrun salient. Ali Muhammad Ali Alyyan (12), his sister Fakhriyeh Muhammad Ali Alyyan (10), and their cousin Khadijeh Abd al Fattah Muhammad Ali (8) were all from Yalo village. Morris wrote, "The two children [Ali and Fakhriyeh] stood in a wadi bed and a soldier opened fire at them. According to both [adult] witnesses only one man fired at them with a sten-gun but none of the detachment attempted to interfere".[24]

In 1961, the population was 1,644 persons.[25]

1967 war

Israeli officials state that Yalo, Imwas and Beit Nuba were destroyed in the course of fighting that took place during the 1967 war. In June 1968, the Israeli embassy in Britain said that "these villages suffered heavy damage during the June war and its immediate aftermath, when our troops engaged two Egyptian Army commando units which had established themselves there and continued fighting after the war."[8]

Tom Segev and Jessica Cohen write that, in 1967, Yalo was one of three populated villages in the Latrun area where Israeli armed forces told residents to leave their homes and gather in an open area outside the villages, after which they were ordered over loudspeakers to march to Ramallah. Segev and Cohen estimate that about 8,000 people left as a result of that order. They also write that, "In the general order distributed to Central Command soldiers, Imwas and Yalu were associated with the failure to take the area in 1948 and were described as 'terms of disappointment, terms of a long and painful account, which has now been settled to the last cent.'"[26]

Amos Kenan, an Israeli soldier present during the operation, later gave a firsthand account of what happened to Yalo and its neighbouring villages. He said that, "The unit commander told us that it had been decided to blow up three villages in our sector; they were Beit Nuba, Imwas and Yalu ... In the houses we found one wounded Egyptian commando officer, and some very old people. At noon the first bulldozers arrived ..."[8] The IDF used bulldozers and explosives to destroy 539 houses in Yalo.[27] In The Case for Palestine, John B. Quigley writes that, "The IDF blew up entire villages of Emmaus, Yalu, and Beit Nuba—near Jerusalem—and drove the villagers toward Jordan."[28]

Meron Benvenisti explains that a week after their expulsion on June 7, 1967, thousands of refugees from the three villages tried to return home but "encountered army roadblocks that had been put up near the villages. From there they watched as bulldozers demolished their homes and the stones from the ruins were loaded on trucks belonging to Israeli contractors, who had bought them to use in building houses for Jews. The village sites, with their verdant orchards, were turned into a large picnic area and given the name Canada Park."[29]

On June 21, 1967, Knesset member Tawfik Toubi requested that Defense Minister Moshe Dayan allow Yalo inhabitants to return to their village, but his request was denied.[27] Michael Oren writes that the Arab villagers were offered compensation by Israel, but were not allowed to return.[30] Since then, the village's evicted residents have campaigned for their return to and reconstruction of Yalo.[27]

Post-2003 development

Since 2003, the Israeli NGO Zochrot ('Remember' in Hebrew) has lobbied the Jewish National Fund for permission to post signs designating the sites of the former Palestinian villages in Canada Park.[31] After petitioning the Israeli High Court,[32] permission was granted. However, subsequently the signs have been stolen or vandalized.[31]

Artistic representations

Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour made Yalo the subject of one of his paintings. The work, named for the village, was one of a series of four on destroyed Palestinian villages that he produced in 1988; the others being Bayt Dajan, Imwas and Yibna.[33]

Demographics

In 1922, at the beginning of British Mandate rule in Palestine, Yalo's population was 811.[17] In 1931 the village's population increased to 963 people, according to a census by British Mandatory authorities.[18] In Sami Hadawi's 1945 land and population survey, its population was 1,220 Arabs.[20]

See also

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 338

- ^ a b "Welcome to Yalu". Palestine Remembered. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ a b Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp. 80-81

- ^ BADIL Occasional Bulletin No. 18 (June 2004). "From the 1948 Nakba to the 1967 Naksa". Badil. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Keinon, H. "Palestinians campaign to regain 'occupied' Latrun". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "Palestinian Emigration and Israeli Land Expropriation in the Occupied Territories". Journal of Palestine Studies. 3 (1). University of California Press on behalf of the Institute for Palestine Studies: 106–118. Autumn 1973. doi:10.1525/jps.1973.3.1.00p0131i. JSTOR 2535530.

- ^ Palestine Remembered

- ^ a b c John Dirlik (October 1991). ""Canada Park" Built on Ruins of Palestinian Villages". Retrieved 2008-08-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Pringle, 1997, pp. 106-107

- ^ Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 152, No 572; cited in Pringle, 1997, p. 107

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 154.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1856, p. 144

- ^ Guérin, 1868, pp. 290-293

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 155

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 118, also noted 67 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 19

- ^ a b Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 15

- ^ a b Mills, 1932, p. 44

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 68

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 117

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 167

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 343

- ^ Morris, 1993, p. 181

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 24 It was further noted (note 2) that it was governed by a mukhtar.

- ^ Segev, 2007, p. 407

- ^ a b c Karmi, 1999, p. 87

- ^ Quigley, 2005, p. 168

- ^ Benvenisti, 2000, p. 327

- ^ Oren, 2002, p. 307

- ^ a b Out of sight maybe, but not out of mind, by Zafrir Rinat, 13 June 2007 Haaretz

- ^ High Court Petition on Canada Park, Zochrot

- ^ Ankori, 2006, p. 82

Bibliography

- Ankori, G. (2006). Palestinian Art. Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-259-4.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 91-93)

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmi, G. (1999). The Palestinian Exodus, 1948-1998. University of London, Centre of Islamic and Middle Eastern Law. Garnet & Ithaca Press. ISBN 0-86372-244-X.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1993). Israel's Border Wars, 1949 - 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827850-0.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Oren, M. (2002). Six Days of War. Oxford University Press. p. 307. ISBN 0-19-515174-7.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Quigley, J.B. (2005). The Case for Palestine: An International Law Perspective. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3539-5, ISBN 978-0-8223-3539-9.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Later Biblical Researches in Palestine and adjacent regions: A Journal of Travels in the year 1852. London: John Murray.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Segev, T.; Cohen, Jessica (2007). 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year that Transformed the Middle East. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7057-6.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To Yalu, Palestine Remembered

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons