Azide

Azide is the anion with the formula N−

3. It is the conjugate base of hydrazoic acid (HN3). N−

3 is a linear anion that is isoelectronic with CO2, NCO−, N2O, NO+

2 and NCF. Per valence bond theory, azide can be described by several resonance structures; an important one being . Azide is also a functional group in organic chemistry, RN3.[1]

The dominant application of azides is as a propellant in air bags.

Preparation

Inorganic azides

Sodium azide is made industrially by the reaction of nitrous oxide, N2O with sodium amide in liquid ammonia as solvent:[2]

- N2O + 2 NaNH2 → NaN3 + NaOH + NH3

Many inorganic azides can be prepared directly or indirectly from sodium azide. For example, lead azide, used in detonators, may be prepared from the metathesis reaction between lead nitrate and sodium azide. An alternative route is direct reaction of the metal with silver azide dissolved in liquid ammonia.[3] Some azides are produced by treating the carbonate salts with hydrazoic acid.

Organic azides

The principal source of the azide moiety is sodium azide. As a pseudohalogen compound, sodium azide generally displaces an appropriate leaving group (e.g., Br, I, OTs) to give the azido compound. Aryl azides may be prepared by displacement of the appropriate diazonium salt with sodium azide, or trimethylsilyl azide; nucleophilic aromatic substitution is also possible, even with chlorides. Anilines and aromatic hydrazines undergo diazotization, as do alkyl amines and hydrazines.[1]

Appropriately functionalized aliphatic compounds undergo nucleophilic substitution with sodium azide. Aliphatic alcohols give azides via a variant of the Mitsunobu reaction, with the use of hydrazoic acid.[1] Hydrazines may also form azides by reaction with sodium nitrite:[5]

- PhNHNH2 + NaNO2 → PhN3

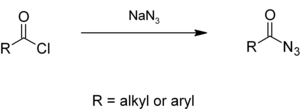

Alkyl or aryl acyl chlorides react with sodium azide in aqueous solution to give acyl azides,[6][7] which give isocyanates in the Curtius rearrangement.

The azo-transfer compounds, trifluoromethanesulfonyl azide and imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide, are prepared from sodium azide as well. They react with amines to give the corresponding azides:

- RNH2 → RN3

Dutt–Wormall reaction

A classic method for the synthesis of azides is the Dutt–Wormall reaction[8] in which a diazonium salt reacts with a sulfonamide first to a diazoaminosulfinate and then on hydrolysis the azide and a sulfinic acid.[9]

Reactions

Inorganic azides

Azide salts can decompose with release of nitrogen gas. The decomposition temperatures of the alkali metal azides are: NaN3 (275 °C), KN3 (355 °C), RbN3 (395 °C), and CsN3 (390 °C). This method is used to produce ultrapure alkali metals.[10]

Protonation of azide salts gives toxic hydrazoic acid in the presence of strong acids:

- H+ + N−

3 → HN3

Azide salts may react with heavy metals or heavy metal compounds to give the corresponding azides, which are more shock sensitive than sodium azide alone. They decompose with sodium nitrite when acidified. This is a method of destroying residual azides, prior to disposal.[11]

- 2 NaN3 + 2 HNO2 → 3 N2 + 2 NO + 2 NaOH

Many inorganic covalent azides (e.g., chlorine, bromine, and iodine azides) have been described.[12]

The azide anion behaves as a nucleophile; it undergoes nucleophilic substitution for both aliphatic and aromatic systems. It reacts with epoxides, causing a ring-opening; it undergoes Michael-like conjugate addition to 1,4-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.[1]

Azides can be used as precursors of the metal nitrido complexes by being induced to release N2, generating a metal complex in unusual oxidation states (see high-valent iron).

Organic azides

Organic azides engage in useful organic reactions. The terminal nitrogen is mildly nucleophilic. Azides easily extrude diatomic nitrogen, a tendency that is exploited in many reactions such as the Staudinger ligation or the Curtius rearrangement or for example in the synthesis of γ-imino-β-enamino esters.[13][14]

Azides may be reduced to amines by hydrogenolysis[15] or with a phosphine (e.g., triphenylphosphine) in the Staudinger reaction. This reaction allows azides to serve as protected -NH2 synthons, as illustrated by the synthesis of 1,1,1-tris(aminomethyl)ethane:

- 3 H2 + CH3C(CH2N3)3 → CH3C(CH2NH2)3 + 3 N2

In the azide alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition, organic azides react as 1,3-dipoles, reacting with alkynes to give substituted 1,2,3-triazoles.

Another azide regular is tosyl azide here in reaction with norbornadiene in a nitrogen insertion reaction:[16]

Applications

About 250 tons of azide-containing compounds are produced annually, the main product being sodium azide.[17]

Detonators and propellants

Sodium azide is the propellant in automobile airbags. It decomposes on heating to give nitrogen gas, which is used to quickly expand the air bag:[17]

- 2 NaN3 → 2 Na + 3 N2

Heavy metal salts, such as lead azide, Pb(N3)2, are shock-sensitive detonators which decompose to the corresponding metal and nitrogen, for example:[18]

- Pb(N3)2 → Pb + 3 N2

Silver and barium salts are used similarly. Some organic azides are potential rocket propellants, an example being 2-dimethylaminoethylazide (DMAZ).

Other

Because of the hazards associated with their use, few azides are used commercially although they exhibit interesting reactivity for researchers. Low molecular weight azides are considered especially hazardous and are avoided. In the research laboratory, azides are precursors to amines. They are also popular for their participation in the "click reaction" and in Staudinger ligation. These two reactions are generally quite reliable, lending themselves to combinatorial chemistry.

The antiviral drug zidovudine (AZT) contains an azido group. Some azides are valuable as bioorthogonal chemical reporters.

Safety

- Azides are explosophores and toxins.

- Sodium azide is toxic (LD50 oral (rat) = 27 mg/kg) and can be absorbed through the skin. It decomposes explosively upon heating to above 275 °C and reacts vigorously with CS2, bromine, nitric acid, dimethyl sulfate, and a series of heavy metals, including copper and lead. In reaction with water or Brønsted acids the highly toxic explosive hydrogen azide is released.

- Heavy metal azides, such as lead azide are primary high explosives detonable when heated or shaken. Heavy-metal azides are formed when solutions of sodium azide or HN3 vapors come into contact with heavy metals or their salts. Heavy-metal azides can accumulate under certain circumstances, for example, in metal pipelines and on the metal components of diverse equipment (rotary evaporators, freezedrying equipment, cooling traps, water baths, waste pipes), and thus lead to violent explosions.

- Some organic and other covalent azides are classified as highly explosive and toxic: inorganic azides as neurotoxins; azide ions as cytochrome c oxidase inhibitors.

- It has been reported that sodium azide and polymer-bound azide reagents react with dichloromethane and bromoform to form di- and triazidomethane resp., which are both unstable in high concentrations in solution. Various devastating explosions were reported while reaction mixtures were being concentrated on a rotary evaporator. The hazards of diazidomethane (and triazidomethane) have been well documented.[19][20]

- Solid iodoazide is explosive and should not be prepared in the absence of solvent.[21]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d S. Bräse; C. Gil; K. Knepper; V. Zimmermann (2005). "Organic Azides: An Exploding Diversity of a Unique Class of Compounds". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (33): 5188–5240. doi:10.1002/anie.200400657. PMID 16100733.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Müller, Thomas G.; Karau, Friedrich; Schnick, Wolfgang; Kraus, Florian (2014). "A New Route to Metal Azides". Angewandte Chemie. 53 (50): 13695–13697. doi:10.1002/anie.201404561.

- ^ "The phenomenon of conglomerate crystallization in coordination compounds. XXIII: The crystallization behavior of [cis-Co(en)2(N3)(SO3)]·2H2O (I) and of [cis-Co(en)2(NO2)(SO3)]·H2O (II)". Struct.Chem. 4: 235. 1993. doi:10.1007/BF00673698.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ R. O. Lindsay; C. F. H. Allen (1955). "Phenyl azide". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 710.

- ^ C. F. H. Allen; Alan Bell. "Undecyl isocyanate". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 846.

- ^ Jon Munch-Petersen (1963). "m-Nitrobenzazide". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 4, p. 715.

- ^ Pavitra Kumar Dutt; Hugh Robinson Whitehead; Arthur Wormall (1921). "CCXLI.—The action of diazo-salts on aromatic sulphonamides. Part I". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 119: 2088–2094. doi:10.1039/CT9211902088.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Reaction Mechanisms by Jie Jack Li Published 2003 Springer ISBN 3-540-40203-9

- ^ E. Dönges "Alkali Metals" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 475.

- ^ Committee on Prudent Practices for Handling, Storage, and Disposal of Chemicals in Laboratories, Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications, National Research Council (1995). Prudent practices in the laboratory: handling and disposal of chemicals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-05229-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ I. C. Tornieporth-Oetting; T. M. Klapötke (1995). "Covalent Inorganic Azides". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 34 (5): 511–520. doi:10.1002/anie.199505111.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Mangelinckx, S.; Van Vooren, P.; De Clerck, D.; Fülöp, F.; De Kimpea, N. (2006). "An efficient synthesis of γ-imino- and γ-amino-β-enamino esters". Arkivoc (iii): 202–209.

- ^ Reaction conditions: a) sodium azide 4 eq., acetone, 18 hours reflux 92% chemical yield b) isopropyl amine, titanium tetrachloride, diethyl ether 14 hr reflux 83% yield. Azide 2 is formed in a nucleophilic aliphatic substitution reaction displacing chlorine in 1 by the azide anion. The ketone reacts with the amine to an imine which tautomerizes to the enamine in 4. In the next rearrangement reaction nitrogen is expulsed and a proton transferred to 6. The last step is another tautomerization with the formation of the enamine 7 as a mixture of cis and trans isomers

- ^ https://www.organic-chemistry.org/synthesis/N1H/reductionsazides.shtm

- ^ Damon D. Reed; Stephen C. Bergmeier (2007). "A Facile Synthesis of a Polyhydroxylated 2-Azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane". J. Org. Chem. 72 (3): 1024–6. doi:10.1021/jo0619231. PMID 17253828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Horst H. Jobelius, Hans-Dieter Scharff "Hydrazoic Acid and Azides" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_193

- ^ Shriver and Atkins. Inorganic Chemistry (Fifth Edition). W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, pp 382.

- ^ M. S. Alfred Hassner (1986). "Synthesis of Alkyl Azides with a Polymeric Reagent". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 25 (5): 478–479. doi:10.1002/anie.198604781.

- ^ A. Hassner; M. Stern; H. E. Gottlieb; F. Frolow (1990). "Synthetic methods. 33. Utility of a polymeric azide reagent in the formation of di- and triazidomethane. Their NMR spectra and the x-ray structure of derived triazoles". J. Org. Chem. 55 (8): 2304–2306. doi:10.1021/jo00295a014.

- ^ L. Marinescu; J. Thinggaard; I. B. Thomsen; M. Bols (2003). "Radical Azidonation of Aldehydes". J. Org. Chem. 68 (24): 9453–9455. doi:10.1021/jo035163v. PMID 14629171.