Tulpa

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Tulpa is a concept in mysticism and the paranormal of a being or object which is created through spiritual or mental powers.[1] It was adapted by 20th-century theosophists from Tibetan sprul-pa (Tibetan: སྤྲུལ་པ་, Wylie: sprulpa) which means "emanation" or "manifestation".[2] Modern practitioners use the term to refer to a type of willed imaginary friend which practitioners consider to be sentient and relatively autonomous.[3]

Emanation body

Indian Buddhism

One early Buddhist text, the Pali Samaññaphala Sutta, lists the ability to create a “mind-made body” (manomāyakāya) as one of the "fruits of the contemplative life".[4]: 117 Commentarial texts such as the Patisambhidamagga and the Visuddhimagga state that this mind-made body is how Gautama Buddha and arhats are able to travel into heavenly realms using the continuum of the mindstream (cittasaṃtāna) and it is also used to explain the multiplication miracle of the Buddha as illustrated in the Divyavadana, in which the Buddha multiplied his nirmita or emanated human form into countless other bodies which filled the sky. A Buddha or other realized being is able to project many such nirmitas simultaneously in an infinite variety of forms in different realms simultaneously.[4]: 125–134

The Indian Buddhist philosopher Vasubandhu (fl. 4th to 5th century CE) defined nirmita as a siddhi or psychic power (Pali iddhi, Sankrit: ṛddhi) developed through Buddhist discipline, concentrated discipline (samadhi) and wisdom in his seminal work on Buddhist philosophy, the Abhidharmakośakārikā. Asanga's Bodhisattvabhūmi defines nirmāṇa as a magical illusion and "basically, something without a material basis".[4]: 130 The Madhyamaka school of philosophy sees all reality as empty of essence; all reality is seen as a form of nirmita or magical illusion.[4]: 158

Tibetan Buddhism

Emanation bodies—nirmanakaya, sprulsku, sprul-pa and so on—are connected to trikaya, the Buddhist doctrine of the three bodies of the Buddha. They are usually emanation bodies of celestial beings, though "unrealized beings" such as humans may have their own emanation bodies or even be emanation bodies.[3] For example, the 14th Dalai Lama is considered by some followers to be an emanation-reincarnation or tulku of Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.[5] The 14th Dalai Lama mentioned in a public statement that his successor might appear via emanation while the current Dalai Lama is still alive.[3]

Tulpa

20th century theosophists adapted the concepts of "emanation body"—nirmita, tulku, sprul-pa and others—into the concepts of "tulpa" and "thoughtform".[2] The term “thoughtform” is used as early as 1927 in Evans-Wentz' translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead.[6] John Myrdhin Reynolds, in a note to his English translation of the life story of Garab Dorje, defines a tulpa as “an emanation or a manifestation.”[7]

Alexandra David-Néel

Spiritualist Alexandra David-Néel claimed to have observed these mystical practices in 20th century Tibet.[1] She described tulpas as "magic formations generated by a powerful concentration of thought."[8]: 331 David-Néel believed that tulpas could develop a mind of its own: "Once the tulpa is endowed with enough vitality to be capable of playing the part of a real being, it tends to free itself from its maker's control. This, say Tibetan occultists, happens nearly mechanically, just as the child, when his body is completed and able to live apart, leaves its mother's womb."[8]: 283 She claimed to have created such a tulpa in the image of a jolly Friar Tuck-like monk, which later developed a life of its own and had to be destroyed.[9] David-Néel raised the possibility that her experience was illusory: "I may have created my own hallucination", though she said others could see the thoughtforms that she created.[8]: 176

Thoughtform

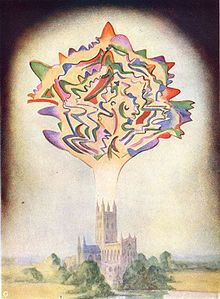

The Western occult understanding of the concept of "thoughtform" is believed by some to have originated as an interpretation of the Tibetan concept of "tulpa".[1] The concept is related to the Western philosophy and practice of magic.[10][page needed] Occultist William Walker Atkinson in his book The Human Aura described thought-forms as simple ethereal objects emanating from the auras surrounding people, generating from their thoughts and feelings.[11] He further elaborated in Clairvoyance and Occult Powers how experienced practitioners of the occult can produce thoughtforms from their auras that serve as astral projections which may or may not look like the person who is projecting them, or as illusions that can only be seen by those with "awakened astral senses".[12] The theosophist Annie Besant, in her book Thought-forms, divides them into three classes: forms in the shape of the person who creates them, forms that resemble objects or people and may become "ensouled" by "nature spirits" or by the dead, and forms that represent "inherent qualities" from the astral or mental planes, such as emotions.[13]

Tulpas in modern society

The concept of tulpa was popularized and secularized in the Western world through fiction, gaining popularity on television in the late 1990s and 2000s.[3] From 2009 onwards, online communities dedicated to tulpas spawned on the 4chan and Reddit websites. These communities collectively refer to themselves as tulpamancers and offer guides and support for other tulpamancers. The communities gained popularity when adult fans of My Little Pony created forums for tulpas of characters from the My Little Pony television series.[14] The fans attempted to use meditation and lucid dreaming techniques to create imaginary friends.[15][16] Surveys by Veissière explored this community's demographic, social, and psychological profiles. These individuals, calling themselves "tulpamancers", treat the tulpas as a "real or somewhat-real person". The number of active participants in these online communities is in the low hundreds, and few meetings in person have taken place. They belong to "primarily urban, middle class, Euro-American adolescent and young adult demographics" and they "cite loneliness and social anxiety as an incentive to pick up the practice." 93.7% of respondents expressed that their involvement with the creation of tulpas has "made their condition better", and led to new unusual sensory experiences. Some practitioners have sexual and romantic interactions with their tulpas, though the practice is controversial and trending towards taboo. One survey found that 8.5% support a metaphysical explanation of tulpas, 76.5% support a neurological or psychological explanation, and 14% "other" explanations.[15]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Campbell, Eileen; Brennan, J. H.; Holt-Underwood, Fran (1994). "Thoughtform". Body, Mind & Spirit: A Dictionary of New Age Ideas, People, Places, and Terms (Revised ed.). Boston: C. E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 080483010X.

- ^ a b Mikles, Natasha L.; Laycock, Joseph P. (6 August 2015). "Tracking the Tulpa: Exploring the "Tibetan" Origins of a Contemporary Paranormal Idea". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 19 (1): 87–97. doi:10.1525/nr.2015.19.1.87.

- ^ a b c d Joffe, Ben (13 February 2016). "Paranormalizing the Popular through the Tibetan Tulpa: Or what the next Dalai Lama, the X Files and Affect Theory (might) have in common". Savage Minds. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d Fiordallis, David (20 September 2008). "Miracles and Superhuman Powers in South Asian Buddhist Literature" (PDF). University of Michigan. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ "Birth to Exile", The Dalai Lama - Biography and Daily Life, The Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, archived from the original on October 19, 2017, retrieved October 10, 2017

- ^ Evans-Wentz, W. T. (2000). The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Or The After-Death Experiences on the Bardo Plane, according to Lāma Kazi Dawa-Samdup's English Rendering. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 29–32, 103, 123, 125. ISBN 0198030517.

- ^ Rinpoche, Dza Patrul (1996). The Golden Letters: The Three Statements of Garab Dorje, the First Teacher of Dzogchen (1st ed.). Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications. p. 350. ISBN 9781559390507.

- ^ a b c David-Neel, Alexandra; DʼArsonval, A. (2000) [Original French published 1929]. Magic and Mystery in Tibet. Escondido, California: Book Tree. ISBN 1585090972.

- ^ Marshall, Richard; Davis, Monte; Moolman, Valerie; Zappler, George (1982). Mysteries of the Unexplained (Reprint ed.). Pleasantville, NewYork: Reader's Digest Association. p. 176. ISBN 0895771462.

- ^ Cunningham, David Michael; Ellwood, Taylor; Wagener, Amanda R. (2003). Creating Magickal Entities: A Complete Guide to Entity Creation (1st ed.). Perrysburg, Ohio: Egregore Publishing. ISBN 9781932517446.

- ^ Panchadsi, Swami (1912). "Thought Form". The Human Aura: Astral Colors and Thought Forms. Yoga Publication Society. pp. 47–54. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Panchadsi, Swami (1916). "Strange astral phenomena". Clairvoyance and Occult Powers. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Besant, Annie; Leadbeater, C. W. (1901). "Three classes of thought-forms". Thought-Forms. The Theosophical Publishing House. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Nathan (2014-09-03). "The Internet's Newest Subculture Is All About Creating Imaginary Friends". Vice. Vice. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ a b Veissière, Samuel (2016), Amir Raz; Michael Lifshitz (eds.), "Varieties of Tulpa Experiences: The Hypnotic Nature of Human Sociality, Personhood, and Interphenomenality", Hypnosis and meditation: Towards an integrative science of conscious planes, Oxford University Press

- ^ T. M. Luhrmbann (2013-10-14). "Conjuring Up Our Own Gods". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-08-12. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- Abstraction

- Concepts in aesthetics

- Concepts in metaphysics

- Concepts in the philosophy of mind

- Buddhist philosophical concepts

- Forteana

- Hallucinations

- History of ideas

- History of philosophy

- History of religion

- Magic (supernatural)

- Metaphysical theories

- Metaphysics of mind

- Mind

- Mysticism

- New Age

- Occult

- Occult collective consciousness

- Paranormal terminology

- Philosophical concepts

- Philosophical theories

- Philosophy of mind

- Philosophy of religion

- Spirituality

- Theosophical philosophical concepts

- Theosophy

- Thought

- Tibetan Buddhist concepts

- Vajrayana