Max Yasgur

Max Yasgur | |

|---|---|

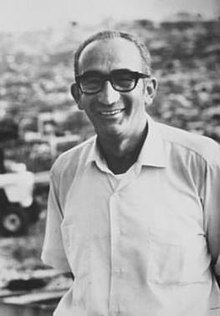

Max Yasgur at the Woodstock Festival in 1969 which was held on part of his dairy farm in Bethel, New York | |

| Born | Max B. Yasgur December 15, 1919 |

| Died | February 9, 1973 (aged 53) |

| Alma mater | New York University |

| Occupation | Farmer |

| Years active | 1949−1971 |

| Known for | Leasing a field of his farm for the purpose of holding the Woodstock Festival |

| Political party | Republican |

| Children | Sam, Lois |

Max B. Yasgur (December 15, 1919 – February 9, 1973) was an American farmer, best known as the owner of the 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, New York, at which the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was held between August 15 and August 18, 1969.

Personal life and dairy farming

Yasgur was born in New York City to Russian Jewish immigrants Samuel and Bella Yasgur.[1] He was raised with his brother Isidore (1926-2010) on the family's farm (where his parents also ran a small hotel)[2] and attended New York University, studying real estate law. By the late 1960s, he was the largest milk producer in Sullivan County, New York.[3] His farm had 650 cows, mostly Guernseys.[4]

At the time of the festival in 1969, Yasgur was married to Miriam (Mimi) Gertrude Miller Yasgur (1920–2014) and had a son, Sam (1942–2016) and daughter Lois (1944–1977). His son was an assistant district attorney in New York City at the time.[4]

In later years, it was revealed that Yasgur was in fact a conservative Republican who supported the Vietnam War.[5][6] Nevertheless, he felt that the Woodstock festival could help business at his farm and also tame the generation gap.[5][7] Despite claims that he showed disapproval towards the treatment of the counterculture movement,[5] this has not been confirmed.[6] Woodstock promoter Michael Lang, who considered Yasgur to be his "hero," stated that Yasgur was "the antithesis" of what the Woodstock festival stood for.[8] Yasgur's early death prevented him from answering questions about why the festival took place.[6]

Woodstock Festival

After area villages Saugerties (located about 40 miles (64 km) from Yasgur's farm) and Wallkill declined to provide a venue for the festival, Yasgur leased one of his farm's fields for a fee that festival sponsors said was $10,000.[4] Soon afterward he began to receive both threatening and supporting phone calls (which could not be placed without the assistance of an operator because the community of White Lake, New York, where the telephone exchange was located, still utilized manual switching).[9] Some of the calls threatened to burn him out. However, the helpful calls outnumbered the threatening ones.[4] Opposition to the festival began soon after the festival's relocation to Bethel was announced. Signs were erected around town, saying, "Local People Speak Out Stop Max's Hippie Music Festival. No 150,000 hippies here" and "Buy no milk"[10]

Yasgur was 49 at the time of the festival and had a heart condition. He said at the time that he never expected the festival to be so large, but that "if the generation gap is to be closed, we older people have to do more than we have done."[4]

Yasgur quickly established a rapport with the concert-goers, providing food at cost or for free. When he heard that some local residents were reportedly selling water to people coming to the concert, he put up a big sign at his barn on New York State Route 17B reading "Free Water." The New York Times reported that Yasgur "slammed a work-hardened fist on the table and demanded of some friends, 'How can anyone ask money for water?'"[4] His son Sam recalled his father telling his children to "take every empty milk bottle from the plant, fill them with water and give them to the kids, and give away all the milk and milk products we had at the dairy."[11]

At the time of the concert, friends described Yasgur as an individualist who was motivated as much by his principles as by the money.[4] According to Sam Yasgur, his father agreed to rent the field to the festival organizers because it was a very wet year, which curtailed hay production. The income from the rental would offset the cost of purchasing thousands of bales of hay.

Yasgur also believed strongly in freedom of expression, and was angered by the hostility of some townspeople toward "anti-war hippies". Hosting the festival became, for him, a "cause".[11]

On the second day of the festival, just before Joe Cocker's early afternoon set, Yasgur addressed the crowd.[12]

After Woodstock

Many of his neighbors turned against him after the festival, and he was no longer welcome at the town general store, but he never regretted his decision to allow the concert on his farm.[11] On January 7, 1970, he was sued by his neighbors for property damage caused by the concert attendees. However, the damage to his own property was far more extensive and, over a year later, he received a $50,000 settlement to pay for the near-destruction of his dairy farm.[13] He refused to rent out his farm for a 1970 revival of the festival, saying, "As far as I know, I'm going back to running a dairy farm".[9]

In 1971, Yasgur sold the 600-acre (2.4 km2) farm, and moved to Marathon, Florida, where, a year and a half later, he died of a heart attack at the age of 53.[9] He was given a full-page obituary in Rolling Stone magazine, one of the few non-musicians to have received such an honor.[14]

In 1997, the site of the concert and 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) surrounding it was purchased by Alan Gerry for the purpose of creating the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. In August 2007, the 103-acre (0.42 km2) parcel that contains Yasgur's former homestead, about three miles from the festival site, was placed on the market for $8 million by its owner, Roy Howard.[15]

In popular culture

Joni Mitchell's song "Woodstock", made famous by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (also covered by Matthews Southern Comfort, Richie Havens, James Taylor, Eva Cassidy, and Brooke Fraser), sings about "going down to Yasgur's Farm".[16]

In addition, Mountain (who were also at the festival) recorded a song shortly after the event entitled "For Yasgur's Farm".

The Beastie Boys 1989 album Paul's Boutique samples Yasgur's Woodstock speech on the track 'Car Thief'.

The progressive rock band Moon Safari has a song titled "Yasgur's Farm" on their album Blomljud.

Yasgur is portrayed by Eugene Levy in Ang Lee's film Taking Woodstock.

Sam Yasgur wrote a book about his father, Max B. Yasgur: The Woodstock Festival's Famous Farmer, in August 2009.[17]

Quotes

I hear you are considering changing the zoning law to prevent the festival. I hear you don't like the look of the kids who are working at the site. I hear you don't like their lifestyle. I hear you don't like they are against the war and that they say so very loudly. . . I don't particularly like the looks of some of those kids either. I don't particularly like their lifestyle, especially the drugs and free love. And I don't like what some of them are saying about our government. However, if I know my American history, tens of thousands of Americans in uniform gave their lives in war after war just so those kids would have the freedom to do exactly what they are doing. That's what this country is all about and I am not going to let you throw them out of our town just because you don't like their dress or their hair or the way they live or what they believe. This is America and they are going to have their festival.

I'm a farmer. I don't know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world--not only to the Town of Bethel, or Sullivan County, or New York State; you've proven something to the world. This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that, you've had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food, and so forth. Your producers have done a mammoth job to see that you're taken care of... they'd enjoy a vote of thanks. But above that, the important thing that you've proven to the world is that a half a million kids--and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you--a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I God bless you for it!

I made a deal with (Woodstock producer) Mike Lang before the festival started. If anything went wrong I was going to give him a crew cut. If everything was OK I was going to let my hair grow long. I guess he won the bet, but I'm so bald I'll never be able to pay it off.

— Life magazine, Special Edition, Woodstock 1969

See also

- Michael Eavis, the English farmer who has hosted the Glastonbury Festival from 1970.

References

- ^ U.S. Census, January 1, 1920, State of New York, County of New York, enumeration district 701, p. 8-A, family 200.

- ^ Green, David B. (9 February 2016). "This Day in Jewish History // 1973: The Farmer Who Defied His Neighbors and Hosted Woodstock Dies". Haaretz.

- ^ "Max Yasgur Tribute Page". woodstockpreservation.org. Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Farmer With Soul:Max Yasgur". The New York Times. 1969-08-17.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c http://www.nashuatelegraph.com/news/local-news/2011/02/09/daily-twip-max-yasgur-who-rented-out-his-farm-as-the-site-of-woodstock-dies-today-in-1973/

- ^ a b c https://canadafreepress.com/article/max-yasgur-the-conservative-republican-who-saved-woodstock

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/1973/02/10/archives/max-yasgur-dies-woodstock-festival-was-on-his-farm-undaunted-by.html

- ^ https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/woodstock-producer-roy-rogers-not-hendrix-could-have-closed

- ^ a b c "Max Yasgur Dies; Woodstock Festival Was on His Farm". The New York Times. 1973-02-09.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Shepard, Richard F. (1969-07-23). "Pop Rockl Festival Finds New Home". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Weaver, Friz (October 30 – November 5, 2008). "County attorney waxes historic". The River Reporter. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Yasgur on Woodstock". YouTube. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ McDougal, Dennis (22 June 1989). "Living Off Woodstock : WOODSTOCK 20 YEARS AFTER : The aging of Aquarius : Whether for Memories or Money, Some Strange Bedfellows Harken Back to That August Weekend". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Max Yasgur : The Real Woodstock Story". Woodstockstory.com. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Yasgur's farm for sale ... for $8 million". Associated Press. 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Joni Mitchell - Woodstock - lyrics". Jonimitchell.com. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Howard (2009-08-15). "Woodstock books bring readers back to Yasgur's farm". The Providence Journal.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Yasgur, Sam. "Book excerpt, Sam Yasgur website". Archived from the original on 2009-09-13. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

External links

- Sullivan County Democrat: Those Who Shaped History

- Sam Yasgur website at the Wayback Machine (archived September 13, 2009)