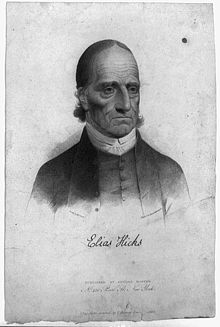

Elias Hicks

Elias Hicks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 19, 1748 |

| Died | February 27, 1830 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Carpenter, Farmer |

| Known for | Traveling Quaker minister |

| Spouse | Jemima Seaman (married January 2, 1771) |

| Children | 11 |

Elias Hicks (March 19, 1748 – February 27, 1830) was a traveling Quaker minister from Long Island, New York. In his ministry he promoted unorthodox doctrines that led to controversy, which caused the second major schism within the Religious Society of Friends. The first being the schism caused by George Keith in 1691. He broke with the Philadelphia Friends Yearly meeting and established a separate Christian Quaker meeting. His followers were called "Keithians" or "Christian Quakers."[1] Elias Hicks was the older cousin of the painter Edward Hicks.

Early life

Elias Hicks was born in Hempstead, New York, in 1748, the son of John Hicks (1711–1789) and Martha Hicks (née Smith; 1709–1759), who were farmers. He was a carpenter by trade and in his early twenties he became a Quaker like his father.[2]

On January 2, 1771, Hicks married a fellow Quaker, Jemima Seaman, at the Westbury Meeting House and they had eleven children, only five of whom reached adulthood. Hicks eventually became a farmer, settling on his wife's parents' farm in Jericho, New York, in what is now known as the Elias Hicks House.[3] There he and his wife provided, as did other Jericho Quakers, free board and lodging to any traveler on the Jericho Turnpike rather than have them seek accommodation in taverns for the night.[4]

In 1778, Hicks helped to build the Friends meeting house in Jericho, which remains a place of Quaker worship. Hicks preached actively in Quaker meeting, and by 1778 he was acknowledged as a recorded minister.[2] Hicks was regarded as a gifted speaker with a strong voice and dramatic flair. He drew large crowds when he was said to be attending meetings, sometimes in the thousands. In November 1829, the young Walt Whitman heard Hicks preach at Morrison's Hotel in Brooklyn, and later said, "Always Elias Hicks gives the service of pointing to the fountain of all naked theology, all religion, all worship, all the truth to which you are possibly eligible—namely in yourself and your inherent relations. Others talk of Bibles, saints, churches, exhortations, vicarious atonements—the canons outside of yourself and apart from man—Elias Hicks points to the religion inside of man's very own nature. This he incessantly labors to kindle, nourish, educate, bring forward and strengthen."[4]

Anti-slavery activism

Elias Hicks was one of the early Quaker abolitionists.

On Long Island in 1778, he joined with fellow Quakers who had begun manumitting their slaves as early as March 1776 (James Titus and Phebe Willets Mott Dodge[5]). The Quakers at Westbury Meeting were amongst the first in New York to do so[6] and, gradually following their example, all Westbury Quaker slaves were freed by 1799.

In 1794, Hicks was a founder of the Charity Society of Jerico and Westbury Meetings, established to give aid to local poor African Americans and provide their children with education.[7]

In 1811, Hicks wrote Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendents and in it he linked the moral issue of emancipation to the Quaker Peace Testimony, by stating that slavery was the product of war.

He identified the economic reason for the perpetuation of slavery:

Q. 10. By what class of the people is the slavery of the Africans and their descendants supported and encouraged? A. Principally by the purchasers and consumers of the produce of the slaves' labour; as the profits arising from the produce of their labour, is the only stimulus or inducement for making slaves.

and he advocated a consumer boycott of slave-produced goods to remove the economic reasons for its existence:

Q. 11. What effect would it have on the slave holders and their slaves, should the people of the United States of America and the inhabitants of Great Britain, refuse to purchase or make use of any goods that are the produce of Slavery? A. It would doubtless have a particular effect on the slave holders, by circumscribing their avarice, and preventing their heaping up riches, and living in a state of luxury and excess on the gain of oppression …[8]

Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendents gave the free produce movement its central argument. This movement promoted an embargo of all goods produced by slave labor, which were mainly cotton cloth and cane sugar, in favor of produce from the paid labor of free people. Though the free produce movement was not intended to be a religious response to slavery, most of the free produce stores were Quaker in origin, as with the first such store, that of Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore in 1826.[9]

Hicks supported Lundy's scheme to assist the emigration of freed slaves to Haiti and in 1824, he hosted a meeting on how to facilitate this at his home in Jericho.[10] In the late 1820s, he argued in favor of raising funds to buy slaves and settle them as free people in the American Southwest.[11]

Hicks influenced the abolition of slavery in his home state, from the partial abolition of the 1799 Gradual Abolition Act to the 1817 Gradual Manumission in New York State Act which led to the final emancipation of all remaining slaves within the state on July 4, 1827.

Doctrinal views

Hicks considered obedience to the Inner Light, to be the sole rule of faith and the foundational principle of Christianity.

Although many accused him of denying the divinity of Christ, the skepticism came because of the unorthodox views he held. He believed that Jesus fulfilled all the law under the Mosaic dispensation and after the last ritual (John's Baptism in water), He became clothed with power from on high to carry out his gospel ministry. He believed the outward manifestation of Jesus was unique to the Jews and that Jesus taught the imminent end of the age of Moses along with all physical outward ordinances, types and shadows. He believed Jesus to be the Christ or Son of God through perfect obedience to the Inner Light, and most commonly referred to him as our "great pattern", encouraging others that they needed to grow in love and righteousness as he did to experience the gospel state.

In the year 1829, "Six Queries" were proposed by Thomas Leggett, Jr., of New York, and answered by Elias Hicks. The last was as follows:

Sixth Query. What relation has the body of Jesus to the Saviour of man? Dost thou believe that the crucifixion of the outward body of Jesus Christ was an atonement for our sins?

Hicks Answered. "In reply to the first part of this query, I answer, I believe, in unison with our ancient Friends, that it was the garment in which he performed all his mighty works, or as Paul expressed it, 'Know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost, which is in you,' therefore he charged them not to defile those temples. What is attributed to that body, I acknowledge and give to that body, in its place, according as the Scripture attributeth it, which is through and because of that which dwelt and acted in it.

"But that which sanctified and kept the body pure (and made all acceptable in him) was the life, holiness, and righteousness of the Spirit. 'And the same thing that kept his vessel pure, it is the same thing that cleanseth us."

"In reply to the second part of this query, I would remark that I 'see no need of directing men to the type for the antitype, neither to the outward temple, nor yet to Jerusalem, neither to Jesus Christ or his blood [outwardly], knowing that neither the righteousness of faith, nor the word of it doth so direct."

"The new and second covenant is dedicated with the blood, the life of Christ Jesus, which is the alone atonement unto God, by which all his people are washed, sanctified, cleansed, and redeemed to God."

Hicks also implicitly refuted the concepts of penal substitution, original sin, the Trinity, predestination, the impossibility of falling from grace, and an external Devil. He never spoke of eternal Hell but he expressed the importance of the soul's union "now" in preparation for the "realms of eternity" and how the soul's condemnation is elected through our free agency, not by God's foreordination.

Hicks was concerned that the present state of the society of friends was settling down in tradition apart from "that ancient power", and that most other Christian professors, had "gone back into the law state and instituted mental shadows and forms", instead of worshiping in spirit and truth through stillness and obedience to the law in the heart. On ministers worshiping in their own will, preparing sermons, he boldly asserted that, "if you took away their notes they would be dumb." He was concerned that most religious profession wasn't founded in experience with the life but was mainly a submission to tradition, superstition, and the mere "letter that kills".[12]

Concerning the scriptures (which many accused him of denying) at the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1826, Hicks expressed a view of the harmful tendencies without a knowledge of the inner light:

Now this seems to be so explained in the writings called the Scriptures, that we might gain a great deal of profitable instruction, if we would read them under the regulating influence of the spirit of God. But they can afford no instruction to those who read them in their own ability; for, if they depend on their own interpretation, they are as a dead letter, in so much, that those who profess to consider them the proper rule of faith and practice, will kill one another for the Scriptures' sake.[13]

Another sentiment from his writings is as follows:

We find, that although these things are so plainly written in the book which we call the Bible, yet we feel and know certainly that there is no power in it to enable us to put in practice what is therein written. [One would suppose that, to a rational mind, the hearing and reading of the instructive parables of Jesus would have a tendency to reform, and turn men about to truth, and lead them on in it. But they have no such effect.]" In the following paragraph he says: "We may read of this; but has the letter ever turned any one to the right thing, unless the light opening it to the understanding has helped him to put in practice what the letter dictates? O that the spirit that dwelt in David might dwell in us; that, from a sense of our impotence and weakness, our prayers might ascend like his; 'Lord show me my secret faults.' And what are these faults that are so various and so many? Why, some are led sway to the worship of images by being deceived and turned aside by tradition and books; they worship other gods beside the true God. [They have been so bound up in the letter, that they think they must attend to it to the exclusion of everything else. Here is an abominable idol worship of a thing with out any life at all, – a dead monument!] Oh! that our minds might be enlightened, – that our hearts might be opened, – that we might know the difference between thing and thing. Most of the worship in Christendom is idolatry, dark and blind idolatry; for all outward worship is so, – it is a mere worship of images. For if we make an image merely in imagination, it is an idol.

Hicks rejected of the notion of an outward Devil as the source of evil, but rather emphasized that it was the human 'passions' or 'propensities'. Hicks stressed that basic urges, including all sexual passions, were neither implanted by an external evil, but all were aspects of human nature as created by God. Hicks claimed, in his sermon Let Brotherly Love Continue at the Byberry Friends Meeting in 1824 that:

He gave us passions—if we may call them passions—in order that we might seek after those things which we need, and which we had a right to experience and know.[14]

Hicks taught that all wrongdoing and suffering occurred in the world as the consequence of "an excess in the indulgence of propensities. Independent of the regulating influence of God's light."[15]

One of the most intriguing ministers the society of friends has ever encountered, he labored earnestly to lead them in what he considered the true new covenant dispensation, an invisible inward covenant and union with God, and saw the tendency that tradition, books, rituals and even the Bible itself had to hinder that light within. Even at 81 years of age, facing heavy opposition from orthodox friends, bodily afflictions, and material in circulation to damage his reputation as a minister, he never wavered in his convictions on placing the sure rule of faith, the law written on the heart, the only thing sufficient to bring each of the children of men to the true peace and love of God. Although liberal friends today claim that he is their founder, many would be uncomfortable with his definition of Christianity: "Nothing more than a complete mortification of our own will, and a full and final annihilation of all self exaltation." On the other hand, conservative friends, would be surprised to find in his own journals and letters, his deep knowledge of scripture and challenging call to true Christianity and self-denial, as, in his words, "It is only in the valley of humiliation that one can have fellowship with the oppressed seed."

Hicksite–Orthodox split

This first split in Quakerism was not entirely due to Hicks' ministry and internal divisions. It was, in part, also a response within Quakerism to the influences of the Second Great Awakening, the revival of Protestant evangelism that began in the 1790s as a reaction to religious skepticism, deism, and the liberal theology of Rational Christianity.

However, doctrinal tensions among Friends due to Hicks' teachings had emerged as early as 1808 and as Hicks' influence grew, prominent visiting English evangelical public Friends, including William Forster and Anna Braithwaite, were prompted to travel to New York State in the period from 1821 to 1827 to denounce his views.[6][16]

Their presence severely exacerbated the differences among American Quakers, differences that had been underscored by the 1819 split between the American Unitarians and Congregationalists.[17] The influence of Anna Braithwaite was especially strong. She visited the United States between 1823 and 1827[18] and published her Letters and observations relating to the controversy respecting the doctrines of Elias Hicks in 1824[19] in which she depicted Hicks as a radical eccentric.[6] Hicks felt obliged to respond and in the same year published a letter to his ally in Philadelphia Meeting, Dr. Edwin Atlee, in The Misrepresentations of Anna Braithwaite.[20] This in turn was replied to by Braithwaite in A Letter from Anna Braithwaite to Elias Hicks, On the Nature of his Doctrines in 1825.[21] Neither party was persuaded by this exchange.

In 1819, Hicks had devoted much energy into influencing the meeting houses in Philadelphia and this was followed by years of intense organizational turmoil.[16] Eventually, due to both external influences and constant internal strife, matters came to a head there in 1826.

After the 1826 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, at which Hicks' sermon had stressed the importance of the Inner Light before Scripture, Quaker elders decided to visit each meeting house in the city to examine the doctrinal soundness of all ministers and elders. This caused great resentment that culminated at the following Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1827. Hicks was not present[22] when the differences between the meeting houses ended in acrimony and division, precipitated by the inability of the Meeting to reach consensus on the appointment of a new clerk[16] required to record its discernment.

Though the initial separation was intended to be temporary, by 1828 there were two independent Quaker groupings in the city, both claiming to be the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Other yearly meetings split along similar lines during subsequent years, including those in New York, Baltimore, Ohio, and Indiana.[23] Those who followed Hicks became termed Hicksites and his critics termed Orthodox Friends, each faction considering itself to be the rightful expression of the legacy of the founder of the Friends, George Fox.

The split was also based on marked socioeconomic factors with Hicksite Friends being mostly poor and rural and with Orthodox Friends being mostly urban and middle-class. Many of the rural country Friends kept to Quaker traditions of "plain speech" and "plain dress", both long-abandoned by Quakers in the towns and cities.

Both the Orthodox and Hicksite Friends experienced further schisms. The main following of the Orthodox Friends followed the practices of the English Quaker Joseph John Gurney who possessed an evangelical position. As time went on, a majority of the meetings endorsed forms of worship much like those of a traditional Protestant church. Those Orthodox Friends who did not agree with the practices of the Gurneyites branched off to form the Wilburite, Conservative, Primitive and Independent yearly meetings. Those Hicksite Friends who did not agree with the lessened discipline within the Hicksite yearly meetings founded Congregational, or Progressive groups.[24]

In 1828, the split in American Quakerism also spread to the Quaker community in Canada that had immigrated there from New York, the New England states and Pennsylvania in the 1790s. This resulted in a parallel system of Yearly Meetings in Upper Canada, as in the United States.

The eventual division between Hicksites and the evangelical Orthodox Friends in the US was both deep and long-lasting. Full reconciliation between them took decades to achieve, from the first reunified Monthly Meetings in the 1920s until finally resolved with the reunification of Baltimore Yearly Meeting in 1968.[25][26]

Later life

On June 24, 1829, at the age of 81, Elias Hicks went on his final traveling ministry to western and central New York State, arriving home in Jericho on November 11, 1829. There, in January 1830, he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and on February 14, 1830, he suffered an incapacitating secondary stroke.[27] He died some two weeks later on February 27, 1830, his dying concern being that no cotton blanket, a product of slavery, should cover him on his deathbed.[28] Elias Hicks was interred in the Jericho Friends' Burial Ground as was earlier his wife, Jemima, who predeceased him on March 17, 1829.[29]

References

- ^ Landsman, Ned C. (1985). Scotland and Its First American Colony, 1683-1765 (first ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 163-176. ISBN 0-691-04724-3.

- ^ a b Timothy L. Hall (2003). American Religious Leaders. Infobase Publishing. p. 169. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ "About the Historic Elias Hicks House" (PDF). Women's Fund of Long Island. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Elias Hicks, Quaker preacher". Long Island Community Foundation. Archived from the original on 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- ^ Swarthmore Friends Historical Library, Westbury Manumissions RecGrp RG2/NY/W453 3.0 1775–1798

- ^ a b c Carol Faulkner (2011). Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 35. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Richard Panchyk (2007). A History of Westbury, Long Island. The History Press. pp. 23, 24. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Elias Hicks (1834). Letters of Elias Hicks, Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendents, (1811). Isaac T. Hopper. pp. 11, 12. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Louis L. D'Antuono (1971). The Role of Elias Hicks in the Free-produce Movement Among the Society of Friends in the United States. Hunter College, Department of History. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Sara Connors Fanning (2008). Haiti and the U.S.: African American Emigration and the Recognition Debate. ProQuest. p. 90. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner; Margaret Hope Bacon, eds. (2010). Back to Africa: Benjamin Coates and the Colonization Movement in America. Penn State Press. p. 6. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ Thomas D. Hamm (1988). The Transformation of American Quakerism: Orthodox Friends, 1800–1907. Indiana University Press. p. 16. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

dvinity hicks.

- ^ "The Blood of Jesus A Sermon and Prayer Delivered by ELIAS HICKS, at Darby Meeting, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, November 15, 1826". Retrieved 2013-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ LET BROTHERLY LOVE CONTINUE/STRENGTHENING THE HAND OF THE OPPRESSOR/FALLEN ANGELS A Sermon Delivered by ELIAS HICKS, at Byberry Friends Meeting, 8th day 12th month, 1824. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ^ Elias Hicks (1825). A series of extemporaneous discourses: delivered in the several meetings of the Society of Friends in Philadelphia, Germantown, Abington, Byberry, Newtown, Falls, and Trenton. Joseph & Edward Parker. p. 166. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ^ a b c Hugh Barbour (1995). Quaker Crosscurrents:Three Hundred Years of Friends in the New York Yearly Meetings. Syracuse University Press. pp. 123, 124, 125. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Thomas C. Kennedy (2001). British Quakerism, 1860–1920: The Transformation of a Religious Community. Oxford University Press. p. 23. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ William Lloyd Garrison (1971). A House Dividing Against Itself, 1836–1840. Harvard University Press. p. 658. ISBN 9780674526617. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ Anna Braithwaite (1824), Letters and observations relating to the controversy respecting the doctrines of Elias Hicks, Printed for the Purchaser, p. 26, retrieved 2013-04-16

- ^ Elias Hicks (1824). The Misrepresentations of Anna Braithwaite. Philadelphia. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ Anna Braithwaite (1825). A Letter from Anna Braithwaite to Elias Hicks, On the Nature of his Doctrines. Philadelphia. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ Elias Hicks (1832). Journal of the life and religious labours of Elias Hicks. I.T. Hopper. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ Margery Post Abbott (2011). Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). Scarecrow Press. p. 167. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Branches of Friends | Quaker Information Center". www.quakerinfo.org. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Thomas D. Hamm (2003). The Quakers in America. Columbia University Press. p. 61. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

1955.

- ^ "Historical Sketch", 4. Quietism, Division and Reunion, Baltimore Yearly Meeting, 2014, retrieved 2014-12-10

- ^ Henry W Wilbur (1910). THE LIFE AND LABORS OF ELIAS HICKS. Philadelphia, Friends' General Conference Advancement Committee. pp. 220, 221. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- ^ Tom Calarco; Cynthia Vogel; Melissa Waddy-Thibodeaux (2010). Places of the Underground Railroad: A Geographical Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 153. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- ^ "Elias Hicks". Find a Grave. February 27, 1830. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- Gross, David M. American Quaker War Tax Resistance (2008) pp. 208–210 ISBN 1-4382-6015-6

External links

- Abbott, The Life and Religious Experience of T. Townsend, Indiana University–Purdue University Fort Wayne (IPFW)

- Anecdotes about Elias Hicks (1888) by Walt Whitman

- Elias Hicks, A Doctrinal Epistle, 1824

- Elias Hicks, "Let Love Be Without Dissimulation", a sermon

- Elias Hicks, "Observations on Slavery"

- Elias Hicks, "Peace, Be Still", a sermon, QH Press

- History of Jericho, NY, Best Schools website

- Larry Kuenning, "Quaker Theologies in the 19th Century Separations", 1 December 1989, submitted at Westminster Theological Seminary

- Observations on the Slavery of Africans and Their Descendants and on the Use of the Produce of Their Labor, by Elias Hicks – from the Antislavery Literature Project

- Pacific Yearly Meeting 2001 Faith and Practice

- "Elias Hicks Manuscript Collection, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College". Swarthmore College. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- Works by Elias Hicks at Project Gutenberg

- Quaker ministers

- American abolitionists

- American Christian universalists

- American Quakers

- American tax resisters

- Christian abolitionists

- Christian universalist clergy

- Christian universalist theologians

- Converts to Quakerism

- People from Hempstead (town), New York

- People from Jericho, New York

- Quaker theologians

- Quaker writers

- Quaker universalists

- 1748 births

- 1830 deaths

- 18th-century Christian universalists

- 19th-century Christian universalists

- 18th-century Quakers

- 19th-century Quakers