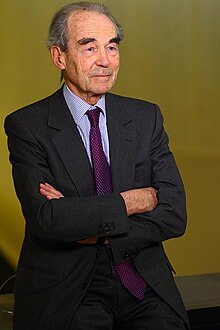

Robert Badinter

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Robert Badinter | |

|---|---|

| |

| French Senator | |

| In office 24 September 1995 – 25 September 2011 | |

| Constituency | Hauts-de-Seine |

| President of the Constitutional Council | |

| In office 19 February 1986 – 4 March 1995 | |

| Appointed by | François Mitterrand |

| Preceded by | Daniel Mayer |

| Succeeded by | Roland Dumas |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 23 June 1981 – 19 February 1986 | |

| President | François Mitterrand |

| Prime Minister | Pierre Mauroy |

| Preceded by | Maurice Faure |

| Succeeded by | Michel Crépeau |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 March 1928 Paris, France |

| Political party | French Socialist Party |

| Spouse | Élisabeth Badinter |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | University of Paris Columbia University |

| Occupation | Lawyer, professor, politician, activist |

Robert Badinter (French: [badɛ̃tɛʁ]; born 30 March 1928) is a French lawyer, politician, and author who enacted the abolition of the death penalty in France in 1981, while serving as Minister of Justice under François Mitterrand. He has also served in high-level appointed positions with national and international bodies working for justice and the rule of law.

Education

Robert Badinter's father Simon was deported and killed in Sobibor, as he was one of the victims of the Rue Sainte-Catherine Roundup in 1943.

Badinter graduated in law from Paris Law Faculty of University of Paris. He then went to United States to continue his studies at Columbia University in New York where he got his MA . He continued his studies again at Sorbonne until 1954.[1]

In 1965, Badinter was appointed as a professor at University of Sorbonne. He has continued as an Emeritus professor until 1996.[2]

Political career

Death penalty

Badinter started his career in Paris in 1951, as a lawyer in a join work with Henry Torres.[3] In 1965, along with Jean-Denis Bredin, Badinter founded the law firm Badinter, Bredin et partenaires, (now Bredin Prat)[4][5] where he practiced law until 1981. Badinter's struggle against the death penalty began after Roger Bontems's execution, on 28 November 1972. Along with Claude Buffet, Bontems had taken a prison guard and a nurse hostage during the 1971 revolt in Clairvaux Prison. While the police were storming the building, Buffet slit the hostages' throats. Badinter served as defense counsel for Bontems. Although it was established during the trial that Buffet alone was the murderer, the jury sentenced both men to death. Applying the death penalty to a person who had not committed the killing outraged Badinter, and he dedicated himself to the abolition of the death penalty.

In this context, he agreed to defend Patrick Henry. In January 1976, 8-year-old Philipe Bertrand was kidnapped. Henry was soon picked up as a suspect, but released because of a lack of proof. He gave interviews on television, saying that those who kidnapped and killed children deserved death. A few days later, he was again arrested, and shown Bertrand's corpse hidden in a blanket under his bed. Badinter and Robert Bocquillon defended Henry, making the case not about Henry's guilt, but against applying the death penalty. Henry was sentenced to life imprisonment and paroled in 2001.

The death penalty was still applied in France on a number of occasions (three people were executed between 1976 and 1981), but its use was increasingly controversial as opinions rose against it.

Ministerial mandate (1981–1986)

In 1981, François Mitterrand was elected president, and Badinter was appointed as the Minister of Justice. Among his first actions was a bill to the French Parliament that abolished the death penalty for all crimes, which the Parliament passed after heated debate on 30 September 1981.

During his mandate, he also gained passage of other laws related to judicial reform, such as:

- Abolition of the "juridictions d'exception" ("special courts"), such as the Cour de Sûreté de l'État ("State Security Court") and the military courts, in time of peace.

- Consolidation of private freedoms (such as the lowering of the age of consent for homosexual sex to make it the same as for heterosexual sex)

- Improvements to the Rights of Victims (any convicted person can make an appeal before the European Commission for Human Rights and the European Court for Human Rights)

- Development of non-custodial sentences (such as community service for minor offences). He remained a minister until 18 February 1986.[citation needed]

1986–1992

From March 1986 to March 1995 he was president of the French Constitutional Council. Since 24 September 1995 he has served as an elected senator in the Parliament, representing the Hauts-de-Seine département.

In 1991, Badinter was appointed by the Council of Ministers of the European Community as a member of the Arbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on Yugoslavia. He was elected as President of the commission by the four other members, all presidents of constitutional courts in the European Community. The Arbitration Commission has rendered eleven advices on "major legal questions" arisen by the split of the SFRY.[6]

Recent times

Badinter continues his struggle against continued use of the death penalty in China and the United States, petitioning officials and working in the World Congress against it.[citation needed]

In 1989, he participated in the French television program Apostrophes, devoted to human rights, together with the 14th Dalaï Lama. Discussing the disappearance of Tibetan culture from Tibet, Badinter used the term "cultural genocide."[7] He praised the example of Tibetan nonviolent resistance.[8] Badinter met with the Dalai Lama many times, in particular in 1998 when he greeted him as the "Champion of Human Rights,"[9] and again in 2008.[10]

Badinter recently opposed the accession of Turkey to the European Union, on the grounds that Turkey might not be able to follow the rules of the Union. He also was concerned about the nation's location, saying: "Why should Europe be neighbour with Georgia, Armenia, Syria, Iran, Iraq, the former Caucasus, that is, the most dangerous region of these times? Nothing in the project of the founding fathers foresaw such an extension, not to say expansion."

As a head of the Arbitration Commission, he gained high respect among Macedonians and other ethnic groups in the Republic of Macedonia because he recommended "that the use of the name 'Macedonia' cannot therefore imply any territorial claim against another State." He supported full recognition of the republic in 1992.[11] Because of that, he was involved in drafting the so-called Ohrid Agreement in the Republic of Macedonia. This agreement was based on the principle that ethnic-related proposals passed by the national assembly (and later to be applied to actions of city councils and other local government bodies) should be supported by a majority of both Macedonians and Albanian ethnic groups. The latter minority comprises about 25% of the population. This is often called the "Badinter principle".

In 2009, Badinter expressed dismay at the Pope's lifting of the excommunication of controversial English Catholic bishop Richard Williamson, who was illegally made a bishop and has denied the Holocaust.[12] The Pope reactivated the excommunication later.

World Justice Project

Badinter serves as an Honorary Co-Chair for the World Justice Project. It works to lead a global, multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the Rule of Law for the development of communities of opportunity and equity.[13]

Personal life

Badinter was born 30 March 1928 in Paris to Simon Badinter and Charlotte Rosenberg.[14] His Bessarabian Jewish family had immigrated to France in 1921 to escape pogroms. During World War II after the Nazi occupation of Paris, his family sought refuge in Lyon. His father was captured and deported with other Jews to the east.[15] He died at Sobibor extermination camp.[citation needed]

Badinter married Élisabeth Bleustein-Blanchet. She is a philosopher, feminist writer, and the daughter of Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet, who is the founder of Publicis.

Summary of political career

- President of the Constitutional Council of France: 1986–1995.

- Political appointee:

- Minister of Justice : 1981–1986 (Resigned when named as President of the Constitutional Council of France).

- Electoral office:

- Senator of Hauts-de-Seine : 1995–2011. Elected in 1995, reelected in 2004.[citation needed]

Bibliography

- L'exécution (1973), about the trial of Claude Buffet and Roger Bontems

- Condorcet, 1743–1794 (1988), co-authored with Élisabeth Badinter.

- Une autre justice (1989)

- Libres et égaux : L'émancipation des Juifs (1789–1791) (1989)

- La prison républicaine, 1871–1914 (1992)

- C.3.3 – Oscar Wilde ou l'injustice (1995)

- Un antisémitisme ordinaire (1997)

- L'abolition (2000), recounting his fight for the abolition of the death penalty in France

- Une constitution européenne (2002)

- Le rôle du juge dans la société moderne (2003)

- Contre la peine de mort (2006)

- Abolition: One Man's Battle Against the Death Penalty, English version of L'abolition (2000), translated by Jeremy Mercer, (Northeastern University Press, 2008)

- Les épines et les roses (2011), on his failures and successes as Minister of Justice

References

- ^ Robert Badinter

- ^ Biographie de Robert Badinter

- ^ Robert Badinter

- ^ Robert Badinter: "The right to life is the most fundamental human right

- ^ "Best Friends", bredinprat

- ^ Curriculum vitae of Robert Badinter, un.org; accessed 12 March 2017.

- ^ Les droits de l'homme Apostrophes, A2 – 21 April 1989 – 01h25m56s, Web site of the INA

- ^ Badinter: "La non- violence tibétaine est exemplaire", lexpress.fr; accessed 12 March 2017.

- ^ Greeting of Mr Robert Badinter and Statement of His Holiness at a public conference

- ^ "Badinter and Dalai Lama", Nouvel Observateur; accessed 12 March 2017.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Evêque négationniste : Robert Badinter s'indigne

- ^ "About". Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ "20ème anniversaire de l'abolition de la peine de mort en France: Robert Badinter, repères biographiques" [20th anniversary of the abolition of the death penalty in France: biography of Robert Badinter]. www.senat.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ Ivry, Benjamin (1 July 2010). "Robert Badinter, Defender of Life and Liberty". Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

External links

- Official page of Robert Badinter in the French Senate

- (in French) La page de Robert Badinter sur le site du Sénat

- (in French) Vidéo: Robert Badinter en 1976, il motive son engagement contre la peine de mort, une archive de la Télévision suisse romande

- (in French) UHB Rennes II : Autour de l'oeuvre de Robert Badinter: Éthique et justice. Synergie des savoirs et des compétences et perspectives d'application en psychocriminologie. "journées d'étude les 22 et 23 mai 2008 à l'université Rennes 2, sur le thème 'Autour de l'œuvre de Robert Badinter: Éthique et justice'"], uhb.fr; accessed 12 March 2017.(in French)

- 1928 births

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- French anti–death penalty activists

- French Jews

- French Ministers of Justice

- French people of Moldovan-Jewish descent

- French Senators of the Fifth Republic

- Human Rights League (France) members

- LGBT rights activists from France

- Living people

- Politicians from Paris

- Recipients of the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

- Socialist Party (France) politicians

- Tibet freedom activists

- Senators of Hauts-de-Seine

- University of Paris alumni

- Columbia University alumni