Burmese Way to Socialism

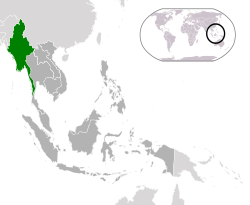

Union of Burma (1962–74) ပြည်ထောင်စု မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော် Pyidaunzu Myăma Nainngandaw Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma (1974–88) ပြည်ထောင်စု ဆိုရှယ်လစ်သမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော် Pyihtaunghcu Soshallaitsammat Myanmar Ninengantaw | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962–1988 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Kaba Ma Kyei Till the End of the World | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Rangoon | ||||||||

| Common languages | Burmese | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | One-party state under a totalitarian military dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1962–1981 (first) | Ne Win[a] | ||||||||

• 1988 (last) | Maung Maung | ||||||||

| Prime minister | |||||||||

• 1962–1974 (first) | Ne Win | ||||||||

• 1988 (last) | Tun Tin | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 2 March 1962 | |||||||||

| 18 September 1988 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1974 | 676,578 km2 (261,228 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Kyat | ||||||||

| Calling code | 95 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Myanmar | ||||||||

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Template:Burmese script The Burmese Way to Socialism (Burmese: မြန်မာ့နည်းမြန်မာ့ဟန် ဆိုရှယ်လစ်စနစ်; also known as the Burmese Road to Socialism) refers to the ideology of the military dictatorship in Burma from 1962 to 1988, which was formed after the 1962 coup d'état led by Ne Win and the military in order to remove Prime Minister U Nu from power. More specifically, the Burmese Way to Socialism is an economic treatise written in April 1962 by the Revolutionary Council, shortly after the coup, as a blueprint for economic development, reducing foreign influence in Burma and increasing the role of the military.[1] The military coup led by Ne Win and the Revolutionary Council in 1962 was done under the pretext of economic, religious and political crises in the country, particularly the issue of federalism and the right of Burmese states to secede from the Union.[2]

The "Burmese Way to Socialism" has largely been described by scholars as being xenophobic, superstitious and an "abject failure", and as turning one of the most prosperous countries in Asia into one of the world's poorest.[3] However, real per capita GDP (constant 2000 US$) in Burma increased from $159.18 in 1962 to $219.20 in 1987, or about 1.3% per year - one of the weakest growth rates in East Asia over this period, but still positive.[4] The program also may have served to increase domestic stability and keep Burma from being as entangled in the Cold War struggles that affected other Southeast Asian nations.[1]

The Burmese Way to Socialism greatly increased poverty, inequality, corruption and international isolation,[5][6] and has been described as "disastrous".[7] Ne Win's later attempt to make the Kyat based in denominations divisible by 9, a number he considered auspicious, wiped out the savings of millions of Burmese. This resulted in the pro-democratic 8888 Uprising, which was violently suppressed by the military, which later established the State Law and Order Restoration Council in 1988.[8]

Background

Under U Nu and the AFPFL-led coalition government, Burma had implemented left-wing economic and welfare policies, although economic growth remained slow throughout the 1950s.[2] On 28 October 1958, Ne Win had staged a coup, under the auspices of U Nu, who asked Ne Win to serve as interim prime minister, to restore order in the country, after the AFPFL split into two factions and U Nu barely survived a motion of no-confidence against his government in parliament. Ne Win restored order during the period known as the Ne Win caretaker government.[9] Elections were held in February 1960 and Ne Win handed back power to the victorious U Nu on 4 April 1960.

By 1958, Burma was largely beginning to recover economically, but was beginning to fall apart politically due to a split in the AFPFL into two factions, one led by Thakins Nu and Tin, the other by Ba Swe and Kyaw Nyein.[10] And this situation persisted despite the unexpected success of U Nu's 'Arms for Democracy' offer taken up by U Seinda in the Arakan, the Pa-O, some Mon and Shan groups, but more significantly by the PVO surrendering their arms.[10] The situation became very unstable in the Union Parliament, with U Nu surviving a no-confidence vote only with the support of the opposition National United Front (NUF), believed to have 'crypto-communists' amongst them.[10]

Army hardliners now saw the 'threat' of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) coming to an agreement with U Nu through the NUF, and in the end U Nu 'invited' Army Chief of Staff General Ne Win to take over the country.[10] Over 400 'communist sympathizers' were arrested, of which 153 were deported to the Coco Island in the Andaman Sea. Among them was the NUF leader Aung Than, older brother of Aung San. Newspapers like Botahtaung, Kyemon and Rangoon Daily were also closed down.[10]

Ne Win's caretaker government successfully established the situation and paved the way for new general elections in 1960 that returned U Nu's Union Party with a large majority.[10] The situation did not remain stable for long, however, as the Shan Federal Movement, started by Nyaung Shwe Saopha Sao Shwe Thaik (the first President of independent Burma from 1948 to 1952) and aspiring to create a 'loose' federation, was seen as a separatist movement insisting on the government honouring the right to secession in 10 years provided for by the 1947 Constitution. Ne Win had already succeeded in stripping the Shan Saophas of their feudal powers in exchange for comfortable pensions for life in 1959.

Ideological features

The "Burmese Way to Socialism" has been described by some commentators as anti-Western, isolationist and socialist in nature,[11] characterised also by an extensive dependence on the military, emphasis on the rural populace, and Burmese (or more specifically, Burman) nationalism.[11] In January 1963, the "Burmese Way to Socialism" was further elaborated in a political public policy called the System of Correlation of Man and His Environment (လူနှင့် ပတ်ဝန်းကျင်တို့၏ အညမည သဘောတရား), was published, as the philosophical and political basis for the Burmese approach to society and what Ne Win deemed as socialism, influenced by Buddhist, humanist and Marxist views.[12][13]

The fundamentals of the "Burmese Way to Socialism", as outlined in 1963, were as follows:

- In setting forth their programmes as well as in their execution the Revolutionary Council will study and appraise the concrete realities and also the natural conditions peculiar to Burma objectively. On the basis of the actual findings derived from such study and appraisal it will develop its own ways and means to progress.

- In its activities the Revolutionary Council will strive for self-improvement by way of self-criticism. Having learnt from contemporary history the evils of deviation towards right or left the Council will with vigilance avoid any such deviation.

- In whatever situations and difficulties the Revolutionary Council may find itself it will strive for advancement in accordance with the times, conditions, environment and the ever-changing circumstances, keeping at heart the basic interests of the nation.

- The Revolutionary Council will diligently seek all ways and means whereby it can formulate and carry out such programmes as are of real and practical value for the well-being of the nation. In doing so it will critically observe, study and avail itself of the opportunities provided by progressive ideas, theories and experiences at home, or abroad without discrimination between one country of origin and another.

The policy sought to reorganize the Burmese economy to a socialist economy, to develop the Burmese military, and to construct a national identity among many disparate ethnic minorities and the majority Burmans.

Impact

The effects of the "Burmese Way to Socialism" were multi-fold, affecting the economy, educational standards, and living standards of the Burmese people. Foreign aid organisations, like the American-based Ford Foundation and Asia Foundation, as well as the World Bank, were no longer allowed to operate in the country.[1] Only permitted was aid from a government-to-government basis. In addition, the teaching of the English language was reformed and moved to secondary schools, whereas previously it had started as early as kindergarten. The government also implemented extensive visa restrictions for Burmese citizens, especially when their destinations were Western countries. Instead, the government sponsored the travel of students, scientists and technicians to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, in order to receive training and to "counter years of Western influence" in the country.[1] Similarly, visas for foreigners were limited to just 24 hours.[14]

Furthermore, freedom of expression and the freedom of the press was extensively restricted. Foreign language publications were prohibited, as were newspapers that printed "false propagandist news."[1] The Press Scrutiny Board (now the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division), which censors all publications to this day, including newspapers, journals, advertisements and cartoons, was established by the RC through the Printers' and Publishers' Registration Act in August 1962.[15] The RC set up the News Agency of Burma (BNA) to serve as a news distribution service in the country, thus effectively replacing the work of foreign news agencies. In September 1963, The Vanguard and The Guardian, two Burmese newspapers, were nationalized. In December 1965, publication of privately owned newspapers was banned by the government.[1]

The impact on the Burmese economy was extensive. The Enterprise Nationalization Law, passed by the Revolutionary Council in 1963, nationalized all major industries, including import-export trade, rice, banking, mining, teak and rubber on 1 June 1963.[1] In total, around 15,000 private firms were nationalized.[2] Furthermore, industrialists were prohibited from establishing new factories with private capital. This was particularly detrimental to the Anglo-Burmese, Burmese Indians and the British, who were disproportionately represented in these industries.

The oil industry, which was previously controlled by American and British companies, such as the General Exploration Company and East Asiatic Burma Oil, were forced to end operations. In its place was the government-owned Burma Oil Company, which monopolized oil extraction and production. In August 1963, the nationalization of basic industries, including department stores, warehouses and wholesale shops, followed.[1] Price control boards were also introduced.

The Enterprise Nationalization Law directly affected foreigners in Burma, particularly Burmese Indians and the Burmese Chinese, both of whom had been influential in the economic sector as entrepreneurs and industrialists. By mid-1963, 2,500 foreigners a week were leaving Burma.[1] By September 1964, approximately 100,000 Indian nationals had left the country.[1]

The black market became a major feature in the economy, representing about 80% of national economy during the Burmese Way period.[2] Moreover, income disparity became a major socioeconomic issue.[2] Throughout the 1960s, Burma's foreign exchange reserves declined from $214 million in 1964 to $50 million in 1971, while inflation skyrocketed.[16] Rice exports also declined, from 1,840,000 tons in 1961-62 to 350,000 tons in 1967-68, the result of the inability of rice production to satisfy demand caused by high population growth rates.

In the First Burmese Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) Congress in 1971, several minor economic reforms were made, in light of the failures of the economic policy pursued throughout the 1960s. The Burmese government asked to rejoin the World Bank, joined the Asian Development Bank, and sought more foreign aid and assistance.[14] The Twenty-Year Plan, an economic plan divided into five increments of implementation, was introduced, in order to develop the country's natural resources, including agriculture, forestry, oil and natural gas, through state development.[14] These reforms brought living standards back to pre-World War II levels and stimulated economic growth.[14] However, by 1988, foreign debt had ballooned to $4.9 billion, about three-fourths of the national GDP, and Ne Win's later attempt to make the Kyat based in denominations divisible by 9, a number he considered to be auspicious, led to the wiping of millions of savings of the Burmese people, resulting in the 8888 Uprising.[14][8]

See also

References

- ^ Titled "Chairman of the Union Revolutionary Council" until 1974

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Holmes, Robert A. (1967). "Burmese Domestic Policy: The Politics of Burmanization". Asian Survey. 7 (3). University of California Press: 188–197. doi:10.1525/as.1967.7.3.01p0257y. JSTOR 2642237.

- ^ a b c d e Aung-Thwin, Maureen; Thant, Myint-U (1992). "The Burmese Ways to Socialism". Third World Quarterly: Rethinking Socialism. 13 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 67–75. JSTOR 3992410.

- ^ McGowan, William (1993). "Burmese Hell". World Policy Journal. 10 (2). The MIT Press and the World Policy Institute: 47–56. JSTOR 40209305.

- ^ "World Development Indicators, GDP per capita (constant 2000 US$) for Myanmar, East Asia & Pacific region". World Bank. Retrieved 23 February 2019 – via Google.

- ^ Thein, Myat (16 January 2018). "Economic Development of Myanmar". Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Retrieved 16 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 13 August 2011. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ (U.), Khan Mon Krann; Development, University of Singapore Center for Business Research & (16 January 2018). "Economic Development of Burma: A Vision and a Strategy". NUS Press. Retrieved 16 January 2018 – via Google Books.

{{cite web}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "Obituary: Ne Win". BBC. 5 December 2002. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Nicholas Tarling, ed. (1993). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. ISBN 0-521-35505-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Smith, Martin (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 49, 91, 50, 53, 54, 56, 57, 58–9, 60, 61, 60, 66, 65, 68, 69, 77, 78, 64, 70, 103, 92, 120, 176, 168–9, 177, 178, 180, 186, 195–7, 193, 202, 204, 199, 200, 270, 269, 275–276, 292–3, 318–320, 25, 24, 1, 4–16, 365, 375–377, 414.

- ^ a b Badgley, John H. (1963). "Burma: The Nexus of Socialism and Two Political Traditions". A Survey of Asia in 1962: Part II. 3 (2). University of California Press: 89–95. doi:10.1525/as.1963.3.2.01p16086. JSTOR 3023680.

- ^ "THE SYSTEM OF CORRELATION OF MAN AND HIS ENVIRONMENT". Burmalibrary.org. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Houtman, Gustaaf (1999). Mental culture in Burmese crisis politics: Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy. ILCAA. ISBN 978-4-87297-748-6.

- ^ a b c d e Steinberg, David I. (1997). "Myanmar: The Anomalies of Politics and Economics" (PDF). The Asia Foundation Working Paper Series (5). Asia Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Butwell, Richard (1972). "Ne Win's Burma: At the End of the First Decade". Asian Survey. 12 (10). University of California Press: 901–912. doi:10.1525/as.1972.12.10.01p02694. JSTOR 2643067.

Other sources

- Revolutionary Council (28 April 1962). "THE BURMESE WAY TO SOCIALISM". Information Department for the Revolutionary Council. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Burma---Growing Ever Darker Foreign Policy in Focus, 11 September 2007.