Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape

Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) is a training program best known by its military acronym that prepares U.S. military personnel, U.S. Department of Defense civilians, and private military contractors to survive and "return with honor" in varied survival scenarios. The curriculum includes survival skills, evading capture, application of the military code of conduct, and methods and techniques for escape from captivity. Formally established by the U.S. Air Force at the end of World War II and the start of the "Cold War", it was extended to the Navy and United States Marine Corps and consolidated within the Air Force during the Korean War with greater focus on "resistance training". During the Vietnam War (1959–1975) there was clear need for "Jungle" survival training and greater public focus on American POWs Prisoner of war. As a result, the U.S. military expanded SERE programs and training sites. In the late 1980s the U.S. Army became more involved with SERE as Special Forces and "Spec Ops" grew. Today, SERE is taught to a wide variety of personnel in three categories based upon risk of capture and exploitation value with high emphasis on aircrew, special operations, and foreign diplomatic and intelligence personnel.

History

“Survival training” for soldiers has ancient origins as survival is an obvious goal of combat [1]. Survival training wasn’t really distinct from “combat training” until navies realized the need to teach sailors to swim. Such training was not related to combat and was intended solely to help sailors survive. Similarly, fire-fighting training has long been a navy focus and remains so today (although survival of the ship may be the primary goal). Water survival training has been a distinct and formal part of Navy basic training since World War II although its importance was greatly increased with the advent and expansion of naval aviation.[2]

The origins of what we now call SERE are rooted in the leadership of Britain's MI-9 Evasion and Escape ("E&E") organization, formed at the onset of World War II (1939-1945). Led by World War I veteran Colonel (later Brigadier) Norman Crockatt[3], MI-9 were formed to train air crew and Special Forces in evading enemy troops following bail out, forced landings, or becoming cut off behind enemy lines. A training school was established in London, and officers and instructors from MI-9 also began visiting operational air bases, providing local training to air crews unable to be detached from their duties to attend formal courses. MI-9 went on to devise a multitude of evasion and escape tools: overt items to aid immediate evasion after bailing out and covert items for use to aid escape following capture that were hidden within uniforms and personal items (concealed compasses, silk and tissue maps, etc.).

Once the United States entered the war in 1941, MI-9 staff travelled to Washington D.C. to discuss their now mature E&E training, devices, and proven results with the United States Army Air Forces ("USAAF"). As a result, the United States initiated their own Evasion and Escape organisation, known as MIS-X, based at Fort Hunt, Virginia[4].

There were also several unofficial private "clubs" created during World War II by British and American pilots who had managed to escape from and evade the Germans during the war and return to friendly lines. One such club was the "Late Arrivals' Club". This strictly non-military club had a "Flying Boot" as its identifying symbol which was worn under the left collar of their uniform.

USAAF General Curtis LeMay realized that it was much cheaper and more effective to train aircrews in Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape techniques than to have them lost in the arctic (or ocean) or languishing (or lost) in enemy hands. Thus, he supported the establishment of formal SERE training at several bases/locations (from July 1942 to May 1944) hosting the 336th Bombardment Group (now the 336th Training Group), including a small program for Cold Weather Survival at RCAF Station Namao in Edmonton, Alberta where American, British, and Canadian B29 aircrews received basic survival training. In 1945, a consolidated survival training center was initiated at Fort Carson, Colorado under the 3904th Training Squadron, and, in 1947 the Arctic Indoctrination Survival School (colloquially known as "the Cool School") opened at Marks Air Force Base in Nome, Alaska.

During WWII, the US Navy discovered that 75 % of its pilots who had been shot or forced down came down alive, yet barely 5 % of them survived because they could not swim or find sustenance in the water or on remote islands. Since the ability to swim was an essential survival skill for navy pilots, training programs were developed to ensure pilot trainees could swim (requiring cadets to swim one mile and dive 50 feet underwater to escape bullets and suction from sinking aircraft). Soon, the training was expanded to include submerged aircraft escape. [5]

During the Korean War (1950-1953) the Air Force moved their survival school to Stead AFB, Reno Stead Airport as the 3635th Combat Crew Training Wing. In 1952, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) designated the United States Air Force (USAF) as executive agent (EA)[6] for escape and evasion activities.

The Korean War showed that traditional notions about captives during wartime were no longer valid – the Koreans (with Chinese backing) simply ignored the Geneva Conventions regarding treatment of POWs and showed that captured American soldiers were not prepared for what they faced. This was especially true of American airmen who took the brunt of mistreatment because of their hated bombardments and their “prestige” among soldiers. The Koreans were very interested in the propaganda value of their American captives and their new methods (with those of the Chinese) for gaining compliance, extracting confessions, and gathering information proved unnervingly successful against American soldiers [7].

Thus, soon after the war ended (without victory) DoD initiated the Defense Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War to study and report on the problems, issues and possible solutions regarding the Korean War POW fiasco. The charter of the committee was to find a suitable approach for preparing our armed forces to deal with the combat and captivity environment.[8]

The committee’s key recommendation was the implementation of a military “Code of Conduct” that embodied traditional American values as moral obligations of soldiers during combat and captivity. Underlying this code was belief that captivity was to be thought of as an extension of the battlefield – a place where soldiers were expected to accept death as a possible duty.[9] President Eisenhower then issued Executive Order 10631 that stated: "Every member of the Armed Forces of the United States are expected to measure up to the standards embodied in the Code of Conduct while in combat or in captivity." The US military then began the process for training and implementing this directive.

While it was accepted that the Code of Conduct would be taught to all US soldiers at the earliest point of their military training, the Air Force knew much more would be needed. At the USAF “Survival School” (Stead AFB), the concepts of evasion, resistance, and escape were expanded and new curricula were developed as “Code of Conduct Training”. That curricula have remained the foundation of modern SERE training throughout the U.S. military.

The Navy also recognized the need for new and different training and by the late 1950s, formal SERE training was initiated at “Detachment SERE” Naval Air Station Brunswick in Maine with a 12-day Code of Conduct course designed to give Navy pilots and aircrew the skills necessary to survive and evade capture, and if captured, resist interrogation and escape. Later, the course was expanded so that other Navy and Marine Corp troops, such as SEALs, SWCC, EOD, RECON / MarSOCC, and Navy Combat Medics would attend. Subsequently, a second school was opened at Naval Air Station North Island.[10]. The Marine Corps opened their Pickel Meadow camp (initially established by Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton) in 1951 where Marines would be trained in outdoor survival and, later, as the Mountain Warfare Training Center (MCMWTC) Bridgeport, California, in Level A SERE.

In 1953 the Army established the “Jungle Operations Training Center” at [[Fort Sherman] in Panama (known as "Green Hell"). Operations there were ramped up during the 1960s to meet the demand for jungle-trained soldiers in Vietnam[11]. In 1958, the Marine Corps opened Camp Gonsalves in northern Okinawa, Japan where jungle warfare and survival training was offered to soldiers headed for Vietnam. As the Vietnam War progressed, the Air Force also opened a "Jungle Survival School" at Clark Air Base in the Phillipines.

When Stead AFB closed in 1966, the USAF "survival school" was moved to Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington State (where it is centered today). The Air Force also had other survival schools including the "Tropical Survival School" at Howard Air Force Base in the Panama Canal Zone, the "Arctic Survival School" at Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska and the "Water Survival School" at Homestead Air Force Base, Florida which operated under separate commands. In April 1971, these schools were brought under the same Group and squadrons were organized to conduct training at Clark, Fairchild and Homestead, while detachments were used for other localized survival training (the acronym “SERE” was not used extensively in the Air Force until later in the 70s).

In 1976, following accusations and reports of abuses during Navy SERE training, DoD established a committee (i.e., “Defense Review Committee”) to examine the need for changes in Code of Conduct training and after hearing from experts and former POWs, they recommended the standardization of SERE training among all branches of the military and the expansion of SERE to include "lessons learned from previous US Prisoner of War experiences" (intending to make the training more "realistic and useful").

In late 1984, the Pentagon issued DoD Directive 1300.7 which established three levels of SERE training with the “resistance portion” incorporated at “Level C”. That level of training was specified for soldiers whose “assignment has a high risk of capture and whose position, rank, or seniority make them vulnerable to greater than average exploitation efforts by a captor”.[12]

While initially only four military bases (Fairchild AFB, SERE), Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Naval Air Station North Island, and Camp Mackall (at Fort Bragg) were officially authorized to conduct C-level training, other bases have been added (such as Fort Rucker). Individual bases may conduct SERE courses which include C-level elements (see "Schools" below). The required (every 3 years) C-level refresher course is commonly taught by USAF “detachments” (often just one SERE specialist/instructor) stationed at a base or a travelling specialist who travels where requested.

The USAF’s 336th Training Group and its 22nd and 66th Training Squadrons are the principle providers of SERE specialists and trainers for the US military (per their designation as SERE EA, as above and modified, as below). This includes the school that trains the only US military career SERE specialists and instructors (the Army and Navy SERE instructors are often graduates of the basic 19-day SERE course (SV-80-A) taught by the 22nd TS, but they have no career option for SERE within their branches. See USAF "Survival Instructors", below). With the largest and best trained SERE staff, the 336th TG assumed diverse roles DoD wide through the 80s, such as furnishing SERE training for Red Flag exercises. In the mid-80s, the USAF Combat "Desert" Survival Course was established by the 3636th Combat Crew Training Wing and USAF Survival Training Schools began emphasizing "Combat SERE Training" (CST) instead of "Global SERE Training".[13]

With the growing importance of personnel recovery (PR), the United States Department of Defense ("DoD") established the Joint Services Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Agency (JSSA) in 1991 and designated it the DoD EA for DoD Prisoner of War / Missing in Action (POW / MIA) matters. In 1994 the JSSA was designated as the central organizer and implementer for PR and the USAF as the EA for Joint Combat Search and Rescue (JCSAR) Combat search and rescue. In 1999, JPRA Joint Personnel Recovery Agency was created as an agency under the Commander in Chief, US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) and was named the Office of Primary Responsibility (OPR) for DoD-wide PR matters. JPRA has been designated a Chairman’s Controlled Activity since 2011.[14]

JPRA has its headquarters at Fort Belvoir and as organizing agency for all DoD "resistance" training, it has close ties with the 336th Training Group (which was given the role of organizing and operating the Personnel Recovery Academy or PRA)[15]. JPRA and the PRA now coordinate PR activities and train PR/SERE globally with American allies making extensive use of USAF SERE experts.

USAF "Survival Instructors"

The first USAF "survival instructors" were experienced civilian wilderness volunteers and USAF personnel with prior instructor experience (and they included a small cadre of "USAF Rescuemen" United States Air Force Pararescue). When the Army Air Force formed the Air Rescue Service (ARS) in 1946, the 5th Rescue Squadron conducted the first Pararescue and Survival School at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida MacDill Air Force Base. With the move to Stead AFB and the opening of a full-time survival school, the USAF initiated the military's only full-time, career survival instructor program (with the Air Force Specialty Code "921"). By the time the Air Force opened the survival school at Fairchild AFB (1966), it also opened a separate "Instructor Training Branch' ("ITB") under the 3636th Combat Crew Training Squadron where all Air Force Survival Instructors received their specialist training (six months of classroom and field training) and initial qualification rating ("Global Survival Instructor"). They then had to complete six months of on-the-job ("OTJ") training before they were qualified to teach SERE (aka "Combat Survival Training" or "CST"). Years of additional training for added specialties (such as artic, jungle, tropics, and water survival, "resistance training", and "academic instruction") to yield some of the best trained soldiers in the U.S. military[16].

Currently, USAF SERE specialist/instructor training is conducted under the 66th Training Squadron at Fairchild AFB. After selection and qualification conducted at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas (SERE specialist orientation course), potential future SERE instructors are assigned to the 66th Training Squadron to learn how to instruct SERE in any environment: the "field" survival course at Fairchild[17], the non-ejection water survival course at Fairchild AFB (which trains aircrew members of non-parachute-equipped aircraft), and the resistance training orientation course (which covers the theories and principles needed to conduct Level C Code of Conduct resistance training laboratory instruction). At some point in their training, USAF SERE specialists also earn their jump wings at the United States Army Airborne School[18]. SERE Specialists who work in the "dunker" portion of the water survival course at Fairchild are are certified through the Navy Salvage Dive Course[19]. The SERE training instructor "7-level" upgrade course is a 19-day course that provides SERE instructors with advanced training in barren Arctic, barren desert, jungle, and open-ocean environments. Today, Air Force SERE specialists are part of Air Force Special Warfare Operations and are utilized in varied roles throughout the Air Force and DoD[20][21][22].

With the US military's only career SERE specialty/specialists, the Air Force's SERE instructors play key roles in DoD-wide training and in implementing other branch SERE training programs (both the Navy and Army send their SERE instructors to take the basic Air Force SERE course).

Levels

Under current DoD public policy, SERE training has three levels[23]:

- Level A: Entry level training. These are the Code of Conduct classes (now commonly taken on-line) required for all military personnel - normally at recruit training ("basic")[24] and "OCS" Officer Candidate School[25].

- Level B: For those operating or expected to operate forward of the division rear boundary and up to the forward line of own troops (FLOT). Normally limited to aircrew of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force. Level B focuses on survival and evasion, with resistance in terms of initial capture.

- Level C: For troops at a high risk of capture and whose position, rank, or seniority make them vulnerable to greater than average exploitation efforts by any captor. Level C training focuses on resistance to exploitation and interrogation, survival during isolation and captivity, and escape from hostiles (e.g., "prison camps")[26].

Curriculum

SERE curriculum has evolved from being primarily focused on "outdoor survival training" to increasingly add focus upon "evasion, resistance, and escape". Military survival training differs from typical civilian programs in several key areas:

- The anticipated military survival situation almost always begins with exiting a vehicle - an aircraft or ship. Thus, the scenario begins with exit strategies, practices, and means (ejecting, parachuting, underwater escape, etc.).

- Military survival training has greater focus on specialized military survival equipment, survival kits, signaling, rescue techniques, and recovery methods.

- Military personnel are almost always better prepared for survival situations because of obvious inherent risk in their activities (and their training and equipment). Conversely, military personnel are subject to a much wider variety of likely scenarios as any given mission may expose them to a wide variety of risks, environments, and injuries.

- In almost all military survival situations someone knows you're missing and will be looking for you with advanced equipment and pre-established protocols.

- Military survival often involves exposure to an enemy.

The basic survival skills taught in SERE programs include common outdoor/wilderness survival skills such as firecraft, sheltercraft, first aid, water procurement and treatment, food procurement (traps, snares, and wild edibles), improvised equipment, self-defense (natural hazards), and navigation (map and compass, et al). More advanced survival training adds focus on mental elements such as will to survive, attitude, and "survival thinking" (situational awareness, assessment, prioritization). Military survival schools also teach unique skills such as parachute landings, basic and specialized signaling, vectoring a helicopter, use of rescue devices (forest-tree penetrators, harnesses, etc.), rough terrain travel, and interaction with indigenous peoples. And then, of course, there are hostile situations...

Combat Survival

The military "has an obligation to the American people to ensure its soldiers go into battle with the assurance of success and survival. This is an obligation that only rigorous and realistic training, conducted to standard, can fulfill"[27]. The U.S. Army has long taken survival training as an integral part of combat readiness (per FM 7-21.13 “The Soldier’s Guide” and FM 5-103 “Survivability”) and combat training is largely about an individual soldier's survival as opposed to the enemy’s non-survival. “Survival”, as a distinct part of modern military training, largely emerges in special environment operations (as shown in “Mountain Operations”, FM 3-97.6, "Jungle School"[28][29], the Marine Corps' mountain warfare training center[30], the Air Force's Desert and Arctic Survival Schools (as above), and the Navy's Naval Special Warfare Cold Weather Detachment Kodiak.

Certain skills have been identified that enhance every soldier's chance for survival (whether they are on the battlefield or not):

- Use weapons properly and effectively

- Move safely and efficiently through various terrains

- Navigate from one point to another given point on the ground

- Communicate as needed

- Perform first aid (evaluate, stabilize, and transport)

- Identify and react properly to hazards

- Select and utilize offensive and defensive positions

- Maintain personal health and readiness

- Evade, resist, and escape (aka "kidnapping and hostage survival")

- Know and utilize emergency procedures, survival equipment, and recovery systems

General Survival

All U.S. military branches recognize the enhanced risks for "special forces" and aircrew personnel. Thus, beyond basic combat skills and their specialty skills, these soldiers should have practical knowledge of survival skills to remain alive and facilitate rescue. Generally, they must have training in:

- Special equipment and procedures intended to enhance their survivability (ejection seats, parachutes, commnication and navigation devices, resuce devices and procedures, etc.)

- Preparing for survival (knowing what to know, what to have, and what to do before you need it)

- Situational awareness and assessment

- Understanding the environment: hazards and opportunities

- Prioritizing needs and planning actions for personal protection, survival, and recovery (survivial decisions)

- If an enemy is involved - evasion (camouflage, travel techniques, et al).

- Shelter (improvised)

- Fire (with and without "starters")

- Water (finding and treaing)

- Signaling (radios, mirrors, fire/smoke, flares, markers)

- Rescue contact and recovery procedures.

- Navigation (generally not advised for military "survival" because rescue is likely)

- Improvisation - an essential survival skill[31]

- Food procurement and preparation (nice to know, but a low priority)

Evasion, Resistance, and Escape

Evading an enemy has certain well-known basic skills, but the military doesn't want to openly discuss its practices since this may assist an enemy. Suffice it to say that major militaries spend considerable time and energy preparing for evasion with extensive planning (routes, practices, pick-up points, methods, "friendlies", "chits", weapons, etc.). Some elements of hostile survival preparedness and teaching are classified. This is especially true for "resistance" training where one hopes to prepare those who might be captured for hardship, stress, abuse, torture, interrogation, indoctrination, and exploitation. The foundation for capture preparedness lies in knowing one's duty and rights if taken prisoner.[32] For American soldiers, this begins with the Code of the United States Fighting Force. It is:

- I am an American, fighting in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.

- I will never surrender of my own free will. If in command, I will never surrender the members of my command while they still have the means to resist.

- If I am captured, I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and to aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.

- If I become a prisoner of war, I will keep faith with my fellow prisoners. I will give no information nor take part in any action which might be harmful to my comrades. If I am senior I will take command. If not, I will obey the lawful orders of those appointed over me and will back them up in every way.

- When questioned, should I become a prisoner of war, I am required to give name, rank, service number, and date of birth. I will evade answering further questions to the utmost of my ability, I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country and its allies or harmful to their cause.

- I will never forget that I am an American, fighting for freedom, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free. I will trust in my God and in the United States of America.[33][34]

Training on how to survive and resist an enemy in the event of capture is generally based on past experiences of captives and prisoners of war. Thus, it is important to know who one's captors are likely to be and what to expect from them. Intelligence regarding such things is sensitive, but in the modern era, captives are less likely to enjoy the status of "prisoner of war" so as to gain protections under the Geneva Conventions relating to such. American soldiers are still taught the standards of international law for humanitarian treatment in war, but they are far less likely to receive them than offer them. Because details cannot be offered, a few examples of well-known resistance methods provide clues as to the nature of resistance techniques:

1. Use of a tap code to secretly communicate between captives.

2. When U.S. Navy Commander Jeremiah Denton was forced to appear at a televised press conference, he repeatedly blinked the word "T-O-R-T-U-R-E" with Morse code.

3. The "code" of prisoners at the "Hanoi Hilton" Hỏa Lò Prison: "Take physical torture until you are right at the edge of losing your ability to be rational. At that point, lie, do, or say whatever you must do to survive. But you first must take physical torture."[35][36]

4. A pilot POW who gave the name of comic book heroes when his captors demanded the name of his fellow pilots.

5. Much from The Great Escape (book).

The teaching of "resistance" is typically done in a "simulation laboratory" setting where "resistance training" instructors act as hostile captors and soldier-students are treated as realistically as possible as captives/POWs with isolation, harsh conditions, close confinement, stress, mock interrogation, and "torture simulations". While it is impossible to simulate the reality of hostile captivity, such training has proven very effective in helping those who have endured captivity know what to expect of their captivity and themselves under such conditions.[37][38]

"Escape Training" has elements similar to evasion and resistance training - if details are revealed, we potentially help adversaries and harm our soldiers. Much of this training has to do with observation, planning, preparation, and contingencies. And much of this comes from historical experience so public sources are revealing (such as the movies The Great Escape (film) and Rescue Dawn).

Special Survival Situations

1. Water (ocean, river, swamp) Survival: Military personnel are much more likly to find themselves in a water survival situation than others. How to survive in water is taught at Navy Recruit Training, Navy SUBSCOL Submarine Escape Training, the Air Force Water Survival Course and at a separate Sof Special ForcesProfessional Military Education (PME) courses. Featured in such courses are topics and exercises such as[39]:

- Underwater escape from vessel/vehicle (from submarines to aircraft)

- Water parachute landing (being dragged through the water by your parachute harness)

- Swimming out from under a parachute (easier said than done)

- Dealing with "rough" water"

- Boarding and getting out of a life raft (the later being easier)

- Life in a raft (care of raft, shade/shelter, use of "sea anchor)

- Use of aquatic survival gear (flotation devices, water desalination, flares, markers...)

- Aquatic environment hazards (from critters to sunburn to dehydration - yes, people die of dehydration in the ocean)

- Aquatic environment first aid (seasickness, immersion injuries, animal injuries)

- Food and water procurement and prepartion (the open ocean "desert"; you can't drink sea water) Digestion requires water.

- Drown-proofing, swimming, floatation

- Special Psychological Concerns (

- Ocean ecology[40]

2. Arctic (sea ice, tundra) Survival: Air Force aircrews spend considerable time flying over arctic regions Polar Routes and while modern arctic survival situations are rare, the training remains useful and worthwhile because its content obviously relates to winter survival anywhere. All U.S. military branches have some type of cold/winter/mountain survival training originating from hard-learned lessons during the Korean War (see above and below). Dealing with cold conditions presents several unique content areas:

- Cold injuries:[41] frostbite, hypothermia, chilblains, immersion foot...

- Snow/Ice/Cold Issues: snowblindness, avalanches/ice fall, icebergs, wind chill

- Staying Warm: Shelter, shelter, shelter. Proper care and use of clothing. Body mechanisms in cold conditions (why a hat is crucial)

- Why an igloo or snow cave is far better than a tent...

- Firecraft: what can you burn when all you see is ice and snow?

- Saving calories, burning calories, and finding calories.

- Arctic/Snow Travel: Where are you going to go? Risk v. Reward. Improvising snowshoes.

- Water (everywhere, but not liquid): Methods for melting.

- Hazards of moisture/Keeping dry

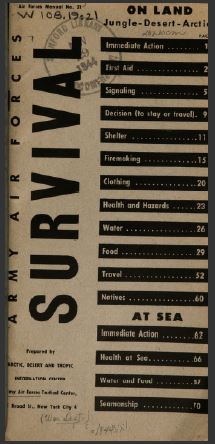

3. Desert Survival: While desert survival training was part of U.S. military survival courses since their inception (see Air Forces Manual No. 21)[42] the focus of survival training went that direction in 1990 with Operation Desert Shield Gulf War (1990-1991). Desert survival training is likely to remain a major focus in the forseeable future. While there is a common mistake to think of deserts as hot, much of the Arctic (and Antarctic) is also desert polar desert. And under the definition of desert climate (a climate in which there is an excess of evaporation over precipitation), some deserts are deemd "cold weather deserts" (such as the Gobi Desert[43]. Because the unifying feature of all deserts is a lack of water, that is the focus for desert survival:

- Conserve water (but don't over-do it): If it's hot, avoid perspiration; if it's cold, avoid dehydrating respiration[44]

- Understanding dehydration (and why`it's a killer)

- Water sources in arid regions

- Hot desert - shelter by day, move/act by night

- Cold desert - trap breath moisture

- Desert shelters (above or below surface)

- Desert garb (the Arab way)

- Desert hazards and treatments

- Desert signalling (smoke and mirrors)

- Desert travel (is that a real mirage or a mirage mirage?)

4. Jungle/Tropics Survival: Staying alive in the jungle is relatively easy, but doing so comfortably can be very difficult. There are good reasons why soldiers deemed JWS (Jungle Warfare School) in Panama "Green Hell"[45]: Constant heat and humidity with frequent rain makes it almost impossible to stay dry. The long list of dangerous plants and animals doesn't usually include the worst - mosquitos. And even if they don't share some dreadul disease with you, mosquitos may annoy you to distraction and bite you into submission. Yes, staying alive in the jungle isn't so much the problem as wanting to.

- It's a Jungle out there: jungle or tropical "rainforest" (Does it matter?)

- The jungle environment: conditions (wet, wetter, wettest)[46], heat index

- Jungle hazards (it's a long list)

- Jungle ailments: trench foot, insect bites, bad food, bad water, parasites, snake bite...

- Food everywhere - if you can stomach it.

- Where's all the water? Water preparartion/treatment

- Jungle shelter(s): "Shingles" and bug barriers, Off the ground?

- Firecraft: getting a "good start" on survival

- Jungle improvisation- so much to work with...

- Jungle signalling and rescue

5. Isolation Survival: Isolation is not just "being alone", it's being away from the familiar and comforting. Isolation survival has long been part of SERE in the "resistance" portion of training, but has more recently been recognized as worthy of broader attention. The psychological impact of suddenly finding yourself alone, lost, or outside your "comfort zone" can be debilitating, seriously depressing, and even fatal (via panic)[47]. Isolation survival also focuses upon the broader view of captivity to include kidnapping and non-combatant captivity. Isolation survival training has more focus on psychological preparedness and less upon "skills"...

- Understanding and avoiding panic

- The importance of "keeping your wits about you"

- Focus, Observe, Plan, and Envision ("FOPE")

- Stress can kill[48]... “fight or flight” coping response, the "stress cycle"[49], and things to help you stay calm[50].

- The psychology of captivity[51]

Service schools

Army

The US Army operates two SERE Level-C courses, one for Army aviators and one for Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF). SERE training for Army aviators is included in the Army Aviation School curriculum at Fort Rucker totaling 21 days of instruction encompassing full-spectrum training including academics and resistance labs.[52] For ARSOF personnel, there's a 19-day SERE course, conducted by the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS), at Camp Mackall. The SWCS's SERE course focuses its training on:[53]

- Code of conduct applications in wartime, peacetime, governmental and/or hostage detention environments

- General survival skills

- Evasion planning

- Resistance to exploitation & political indoctrination

- Escape planning

Level A is taught to recruits and candidates in Officer Candidate School and the Recruit Depots, or under professional military education.

Level B at the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, Bridgeport, California, and at the North Training Area, Camp Gonsalves, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan.

Level C is held at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine at the Navy Remote Training Site, Rangeley, and at Naval Air Station North Island, California at the Navy Remote Training Site, Warner Springs. This installation provides "Code of Conduct" that is necessary for Recon Marines, Marine Corps Scout Snipers, MARSOC Marines, Navy SEALs, enlisted Navy and Marine aircrewmen, Naval Aviators, Naval Flight Officers, Naval Flight Surgeons, Navy EOD, and Navy SWCC. As the "eyes" and "ears" of the commander, they carry knowledge of sensitive battlefield information.

The training encompasses those basic skills necessary for worldwide survival, facilitating search and rescue efforts, evading capture by hostile forces. It is based on and reinforces the values expressed in the Code of Conduct while maintaining an appropriate balance of sound educational methodology and realistic/stressful training scenarios.

Additional survival training in Level C Code of Conduct may include the five-day Peacetime Detention and Hostage Survival (PDAHS) course. This training provides the skills to survive captivity by a hostile government or terrorist cell during peacetime.

Air Force

The largest SERE Course is located at US Air Force Survival School at Fairchild Air Force Base, Washington. The US Air Force Survival School is also home to the USAF SERE Specialist program, the only career-long SERE instructor career field. Each USAF SERE Specialist goes through a grueling selection process and if successful, attends the USAF SERE Specialist Training Course. Those that graduate (less than 10%) are awarded the Sage Beret, SERE Arch and SERE Flash. Following training, the Specialists are tasked with 45 weeks of intensive on-the-job training. Each graduate must attend Airborne School at the US Army Training Center located at Ft. Benning, GA. After completion of four years as an Instructor (Field Training) the Specialist may be tasked to train students worldwide. USAF SERE Specialists are required to complete an associate degree in Survival and Rescue Sciences through the USAF Community College in order to continue to advance in their career field.

SERE Specialists complete additional qualification training at specialized schools as required. Examples are Scuba Courses, Military Freefall Parachuting, Altitude chamber, etc. Assignment to each of the outlying schools requires additional training by the SERE Specialist. Upon reporting to the new assignment, each SERE Specialist must first complete that school's course (the same as an Aircrew member), and then be trained by the school's cadre in the specialized subject matter (and carry crews under supervision) before the newly assigned Specialist is "qualified" to teach without supervision. At Edwards AFB, USAF SERE Specialists are tasked as "Test Parachutists" and required to perform multiple jumps on newly introduced / modified rescue systems, aircraft, and parachuting and / or ejection systems. This includes test parachuting newly designed canopies, harnesses, etc. Currently, they are the only Test Parachutists in the Department of Defense. USAF SERE Specialists are considered DOD-wide subject matter experts in their field and are assigned to base level and command staff as advisers.

Level B SERE training in the Air Force is conducted at Lackland Air Force Base under the name Evasion and Conduct After Capture (ECAC).[54] Student training for Level B medical aircrew was conducted at Brooks City-Base, Texas until the planned course closure on 30 September 2009. The Air Force conducts Arctic Survival Training – Cool School at Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska, and Parachuting and Non-Parachuting Water Survival Training at Fairchild AFB, Washington. The parachute water survival training—which was once located in Florida—ceased operations there in August 2015.

SERE training was also conducted at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs from the late 1960s until 1995, enabling those USAF officers commissioned through USAFA to exempt from USAF SERE training at Fairchild AFB following undergraduate pilot or navigator training. In contrast, those USAF officers commissioned through AFROTC or OTS still had to complete SERE at Fairchild following flight training. In 1995, the resistance/escape element of the course at USAFA was abolished (see Controversies below), leaving the survival and evasion classes in a program called Combat Survival Training (CST) until 2005. In the summer 2008 some portions of the program, including resistance training, were reinstated. Following the summer of 2011, the scope of the CST program was reduced drastically and incorporated into the mandatory expeditionary skills training for budgetary reasons.[55] Now, all USAFA graduates selected for pilot, air battle manager, or navigator training must complete SERE training at Fairchild after receiving their wings, along with their AFROTC and OTS graduate counterparts.

Origin of SERE techniques

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2020) |

The SERE techniques are commonly,[56] but erroneously,[citation needed] believed to be modeled on abusive Chinese "brainwashing" practiced on U.S. POWs during the Korean War, to extract false confessions.[57][58][59] Instead, most SERE techniques were modeled after 1950s and early 1960s CIA interrogation and psychological warfare practices.[60] The CIA physical and psychological methods were originally codified in the Kubark Counterintelligence Interrogation Manual published in 1963, and in CIA torture training handbooks for Latin American regimes published in the 1970s and 1980s, and were employed during the Cold War, the CIA's Phoenix Program in Vietnam, and the Chilean intelligence organization DINA's Operation Condor in South America.[61] The other primary source for SERE techniques was 1960s CIA "mind control experiments", using sleep deprivation, drugs, electric shock, and isolation and extended sensory deprivation.[62] Certain of the less physically damaging CIA methods, derived from what was at the time called "defensive behavioral research", were reduced and refined as training techniques for the SERE program.[63]

Controversies

In 1976, Lieutenant Wendell Richard Young, a former student, filed a $15 million suit against the Warner Spring school, after breaking his back during training. Investigating his claims, Newsweek found instances of waterboarding. A committee was also formed to interview ex-POWs and find out about torture methods used by the US military.[64]

1995 U.S. Air Force Academy scandal

One of the U.S. Air Force's SERE training programs was conducted at the United States Air Force Academy from the late 1960s until 1995. Because a large number of pilots and other aircrew members graduated from the academy, it was more efficient for the Air Force to send all cadets through SERE training while they were still at the academy. Cadets would normally complete the training during the summer between their fourth-class (freshman) and third-class (sophomore) years. A number of selected second-class (junior) and first-class (senior) cadets would serve each year as SERE training cadre under the supervision of enlisted Air Force SERE instructors.

As a result of POWs' experiences during Operation Desert Storm (1990–1991), sexual assault resistance was added to the SERE curriculum. However, some of the training scenarios allegedly were taken too far by SERE cadet members at the academy during practical portions of the program. In 1995, the ABC television news program 20/20 reported that as many as 24 male and female cadets in 1993 had allegedly been sexually assaulted at the Academy during SERE training. One of the cadets sued the U.S. federal government, which eventually settled for a reported US$3 million in damages.[65]

As a result of the scandal, the SERE program at the Academy was reduced to the survival and evasion portions only, and the curriculum was revamped to be in line with the main course at Fairchild AFB titled: "Combat Survival Training (CST)". All graduates going on to aircrew positions were then required to attend the resistance portion of the training at Fairchild Air Force Base before reporting to an operational flying unit. The CST program was discontinued entirely in 2004. The Air Force Academy SERE program is running as of summer of 2008[update]. The curriculum of the revived program will contain some resistance elements, but will not contain sexual assault resistance.[55]

Use of techniques in interrogation

In July 2005, an article[66] in The New Yorker magazine alleged that psychologists who help direct the SERE curriculum have been advising the military at Guantanamo Bay detainment camp and other sites on interrogation techniques.

The SERE program's chief psychologist, Colonel Morgan Banks, issued guidance in early 2003 for the "behavioral science consultants" who helped to devise Guantánamo's interrogation strategy although he has emphatically denied that he had advocated the use of counter-resistance techniques used by SERE instructors to break down detainees. The New Yorker notes that in November 2001, Banks was detailed to Afghanistan, where he spent four months at Bagram Air Base, "supporting combat operations against Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters".

In June 2006, an article on Salon, an online magazine, confirmed finding a document obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union through the Freedom of Information Act. A March 22, 2005, sworn statement by the former chief of the Interrogation Control Element at Guantánamo said SERE instructors taught their methods to interrogators of the prisoners in Cuba.[67] The article also claims that physical and mental techniques used against some detainees at Abu Ghraib are similar to the ones SERE students are taught to resist.

According to Human Rights First, the interrogation that led to the death of Iraqi Major General Abed Hamed Mowhoush involved the use of techniques used in SERE training. According to the organization "Internal FBI memos and press reports have pointed to SERE training as the basis for some of the harshest techniques authorized for use on detainees by the Pentagon in 2002 and 2003."[68]

On June 17, 2008, Mark Mazzetti of The New York Times reported that the senior Pentagon lawyer Mark Schiffrin requested information in 2002 from the leaders of the Air Force's captivity-resistance program, referring to one based in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The information was later used on prisoners in military custody.[69] In written testimony to the Senate Armed Forces Committee hearing, Col. Steven Kleinman of the Joint Personnel Recovery Agency said a team of trainers whom he was leading in Iraq were asked to demonstrate SERE techniques on uncooperative prisoners. He refused, but his decision was overruled. He was quoted as saying "When presented with the choice of getting smarter or getting tougher, we chose the latter."[70] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has acknowledged that the use of the SERE program techniques to conduct interrogations in Iraq was discussed by senior White House officials in 2002 and 2003.[71]

Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture

On December 9, 2014, the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released a report further confirming the use of SERE tactics in interrogations.[72] The contractors who developed the "enhanced interrogation techniques" received US$81 million for their services, out of an original contract worth more than US$180 million. NBC News identified the contractors, who were referred to in the report via pseudonyms, as Mitchell, Jessen & Associates from Spokane, Washington, which was run by two psychologists, John "Bruce" Jessen and James Mitchell. Jessen was a senior psychologist at the Defense Department who taught special forces on how to resist and endure torture. The report states that the contractor "developed the list of enhanced interrogation techniques and personally conducted interrogations of some of the CIA's most significant detainees using those techniques. The contractors also evaluated whether the detainees' psychological state allowed for continued use of the techniques, even for some detainees they themselves were interrogating or had interrogated." Mitchell, Jessen & Associates developed a "menu" of 20 enhanced techniques including waterboarding, sleep deprivation and stress positions. The CIA acting general counsel, described in his book Company Man, that the enhanced techniques were "sadistic and terrifying."[73]

See also

- Enhanced interrogation techniques

- Resistance to interrogation

- Special Activities Division

- Survive, Evade, Resist, Extract—an analogous training program used by the armed forces of the United Kingdom

References

- ^ “Every soldier, regardless of rank, position, and MOS must be able to shoot, move, communicate, and survive in order to contribute to the team and survive in combat.” Army FM 7-21.13 (“The Soldier’s Guide”), p. A-1

- ^ https://bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com/military-training/armed-forces-of-the-united-states-of-america/us-navy-phase-1-basic-military-training-aka-us-navy-boot-camp/

- ^ https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/escape-master-wwii-norman-crockatt.html

- ^ http://www.fortwiki.com/Fort_Hunt

- ^ https://swimswam.com/teaching-americas-wwii-navy-fighter-pilots-to-swim/

- ^ The DoD defines Executive Agency or “EA” as “the Head of a DOD Component to whom the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) or the Deputy Secretary of Defense (DEPSECDEF) has assigned specific responsibilities, functions, and authorities to provide defined levels of support for operational missions, or administrative or other designated activities that involve two or more of the DOD Components.” See https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN3387_AR10-90_Web_FINAL.pdf

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130316204551/http://www.kunsan.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123241828

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130316204551/http://www.kunsan.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123241828

- ^ It wasn’t until 1977 that the code was modified with the intent to make it more practical by removing or changing wording that implied death was often the most suitable course of action.

- ^ https://www.netc.navy.mil/ https://www.mnp.navy.mil/group/security-forces

- ^ https://www.wearethemighty.com/military-life/why-jungle-warfare-school-was-called-a-green-hell#:~:text=Training%20began%20in%20earnest%20in,the%20tactics%20of%20jungle%20warfare.&text=Operations%20ramped%20up%20once%20again,soldiers%20to%20fight%20in%20Vietnam.

- ^ https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blaw/dodd/corres/pdf2/d13007p.pdf

- ^ https://www.baseops.net/militarybooks/usafsurvival.html

- ^ https://www.jpra.mil/

- ^ https://www.jpra.mil/links/Training/PRA.html

- ^ https://bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com/elite-special-forces/us-elite-special-forces/afsoc-us-air-force-special-operations-command/us-air-force-sere-specialist-selection-training/

- ^ “Inside America’s Toughest Survival School”, by Clint Carter at https://www.mensjournal.com/adventure/inside-air-force-survival-training/

- ^ https://www.thebalancecareers.com/usaf-sere-career-profile-2356491

- ^ https://www.fairchild.af.mil/News/Features/Display/Article/763075/sere-water-survival-preparing-airmen-for-the-sea/

- ^ [https://www.airforcemag.com/sere-specialists-working-to-expand-their-ranks-improve-recruitment/

- ^ [https://www.mensjournal.com/adventure/inside-air-force-survival-training/

- ^ [http://www.richwritings.com/article%20a18.htm

- ^ See Army Regulation 350–30: “Training Code of Conduct, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE)” at https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/ar350-30.pdf

- ^ https://www.todaysmilitary.com/joining-eligibility/boot-camp

- ^ https://jkosupport.jten.mil/Atlas2/page/coi/externalCourseAccess.jsf?v=1592353083012&course_prefix=J3T&course_number=A-US1329

- ^ https://www.army.mil/article/138765/sere_training_develops_leaders_for_complex_environment

- ^ FM 7-21.13 (“The Soldier’s Guide”), p. 5-2

- ^ https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2017/03/16/soldiers-train-for-jungle-warfare-at-hawaii-rainforest/

- ^ https://www.thebalancecareers.com/marine-corps-sere-training-3332803

- ^ https://www.29palms.marines.mil/mcmwtc/About/History/

- ^ For example: https://survivalschool.us/9-improvised-survival-items-that-could-save-your-life/ or https://mypatriotsupply.com/blogs/scout/the-one-survival-skill-you-might-be-missing

- ^ [https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2015/11/13/navy-legend-vice-adm-stockdale-led-pow-resistance/

- ^ Code of Conduct, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Training, U.S. Army Regulation 350-30, December 10, 1985

- ^ USAFA 2010–2011 Contrails

- ^ [https://web.archive.org/web/20090630160225/http://www.philly.com/inquirer/currents/20090607_SURVIVING_TORTURE.html

- ^ [https://historycollection.co/this-medal-of-honor-recipient-was-executed-for-singing-god-bless-america/2/

- ^ [http://wsm.wsu.edu/s/index.php?id=682

- ^ [https://www.businessinsider.com/heres-what-its-like-at-sere-training-2014-12

- ^ AFM 64-3 "Survival Training Edition"(1977); NAVAER 00-80T-56, "SURVIVALTRAINING GUIDE" (1955)

- ^ https://enlistspecialforces.wordpress.com/sf-training-pipeline/sf-sere-school/

- ^ Nagpal, BM; Sharma, R (2004). "Cold Injuries : The Chill Within". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 60 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80111-4. PMC 4923033.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=ILDe_J2czBMC&pg=PP1&dq=Air+Forces+Manual+survival+1944&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiE4fCd_J3qAhXB7Z4KHRZVAk0Q6AEwAXoECAIQAg#v=onepage&q=Air%20Forces%20Manual%20survival%201944&f=false

- ^ https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/deserts/types/

- ^ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22714078/

- ^ https://www.wearethemighty.com/military-life/why-jungle-warfare-school-was-called-a-green-hell

- ^ "The dry season in a jungle means it rains once a day." https://adventure.howstuffworks.com/survival/wilderness/jungle-survival.htm

- ^ For a broad view of this, see https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/nation/what-isolation-does-to-your-brain

- ^ https://www.stress.org/can-stress-kill-you

- ^ https://psychcentral.com/blog/the-stress-reaction-cycle/

- ^ https://www.psychologicalhealthcare.com.au/blog/keep-calm-pressure/

- ^ https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-01725-005; "Seasons of Captivity: The Inner World of POWs" by Amia Lieblich, NYU Press (1994) ("The Psychology of Captivity" available in preview at https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=A433Oo6Kk9EC&oi=fnd&pg=PP3&dq=psychology+of+captivity&ots=YMwbxfP_Sv&sig=iH9w7_nPmMJ1HszwRYpNIjXWKWA#v=onepage&q=psychology%20of%20captivity&f=false

- ^ SERE training develops leaders for complex environment, Army.mil, by CPT Erik Olsen, dated 21 November 2014, last accessed 22 April 2017

- ^ Survival, Evasion Resistance and Escape (SERE) Course (PHASE II SFQC), U.S. Army Special Operations Center of Excellence, last accessed 22 April 2017

- ^ http://www.jbsa.mil/News/News/Article/1877894/sere-specialists-showcase-training-for-recruiters, SERE Specialists showcase training for recruits, AF.mil, by 1st Lt Kayshel Trudell, dated 14 June 2019, last accessed 8 September 2019,

- ^ a b Swanson, Perry (12 January 2008). "Hostage Training to Resume for Cadets". The Gazette. Colorado Springs. Retrieved 2008-01-14.[permanent dead link]

- ^ For example, the Senate Armed Services Committee Report on abuse of detainees at Guantanamo, Abu Ghraib, and CIA black site prisons reiterates the popular misconception that SERE techniques originated in Chinese Communist methods in the Korean War employed to extract false confessions from US POWs. Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in U.S. Custody, Report of the Committee on Armed Services of the U.S. Senate, November 20, 2008, 110th Cong. 2nd Sess. (U.S. Gov't Printing Office).

- ^ Shane, Scott (July 2, 2008). "China Inspired Interrogations at Guantánamo". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Biderman, Albert D. (September 1957). "Communist Attempts to Elicit False Confessions from Air Force Prisoners of War". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 33 (9): 616–625. PMC 1806204. PMID 13460564.

- ^ A 1956 U.S. Department of the Army report called physical and psychological abuse resulting in brainwashing a "popular misconception"; there was not a single reliable report of brainwashing.U.S. Department of the Army (15 May 1956). Communist Interrogation, Indoctrination, and Exploitation of Prisoners of War. U.S. Gov't Printing Office. pp. 17 & 51. Pamphlet No. 30-101.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred (2007). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Henry Holt & Co. pp. 10, 50–51, 71. ISBN 978-0-8050-8248-7.

- ^ McCoy, A Question of Torture, 2007, pp. 63–67, 89, 91–93

- ^ McCoy, A Question of Torture, 2007, p. 250

- ^ McCoy, A Question of Torture, 2007, p. 26

- ^ Otterman, Michael. American Torture: From the Cold War to Abu Ghraib and Beyond, Melbourne University Press, 2007.

- ^ Charles, Roger (2004-03-04). "AFA Scandals Confirm Senate Oversight Failure". DefenseWatch. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (2005-07-11). "THE EXPERIMENT: The military trains people to withstand interrogation. Are those methods being misused at Guantánamo?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- ^ Benjamin, Mark (2006-06-29). "Torture teachers". Salon. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- ^ Hina Shamsi; Deborah Pearlstein, ed. "Command's Responsibility: Detainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and Afghanistan: Abed Hamed Mowhoush" Archived 2006-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights First, February 2006. Accessed 4 August 2008.

- ^ Mark Mazzetti. "Ex-Pentagon Lawyers Face Inquiry on Interrogation Role". The New York Times, June 17, 2008.

- ^ Kleinman, Steven. "Officer: Military Demanded Torture Lessons". CBS News, July 25, 2008.

- ^ Rice, Condoleezza (September 26, 2008). "Rice admits Bush officials held White House talks on CIA interrogations". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. "The Senate Committee's Report on the C.I.A.'s Use of Torture". December 9, 2014.

- ^ Windrem, Robert. "CIA Paid Torture Teachers More than $80 Million". NBC News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

Further reading

- Christopher Hitchens, "Believe Me, It's Torture", Vanity Fair, August 2008

- David J. Morris (January 29, 2009). "Cancel Water-Boarding 101; The military should close its torture school. I know because I graduated from it". Slate.

External links

- USAF SERE Community Site

- US Navy SERE training (Brunswick)

- Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA)

- New Yorker magazine article about SERE

- Army Regulation for Code of Conduct/ SERE Training

- DOD directive on SERE training (DODI 1300.21) l

- DOD directive regarding isolated personnel training (DODI 1300.23)

- A narrative of SERE Instructor School

- Video to promote SERE recruitment