An Wasserflüssen Babylon

It has been suggested that details regarding Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon be split out into another article titled An Wasserflüssen Babylon (Reincken). (Discuss) (March 2018) |

| "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" | |

|---|---|

| Lutheran hymn | |

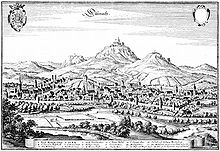

Super Flumina Babylonis, "An Wasserflüssen Babylon," from the 1541 Straßburger Gesangbuch | |

| Text | Wolfgang Dachstein |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Psalm 137 |

| Published | 1525 |

"An Wasserflüssen Babylon" (By the rivers of Babylon) is a Lutheran hymn by Wolfgang Dachstein, which was first published in Strasbourg in 1525. The text of the hymn is a paraphrase of Psalm 137. Its singing tune, which is the best known part of the hymn and Dachstein's best known melody, was popularised as chorale tune of Paul Gerhardt's 17th-century Passion hymn "Ein Lämmlein geht und trägt die Schuld". With this hymn text, Dachstein's tune is included in the Protestant hymnal Evangelisches Gesangbuch.

Several vocal and organ settings of the hymn "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" have been composed in the 17th and 18th century, including 4-part harmonisations by Johann Schein, Heinrich Schütz and Johann Sebastian Bach. In the second half of the 17th century, Johann Pachelbel, Johann Adam Reincken and Bach's cousin, Johann Christoph, arranged settings for chorale preludes.

The arrangements of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" by Reincken and Pachelbel form the earliest extant transcriptions of Bach, copied on a 1700 organ tablature in Lüneburg when he was still a youth; remarkably, they were only unearthed in Weimar in 2005.

In 1720, in a celebrated organ concert at Hamburg, Bach extemporised a chorale setting of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" in the presence of Reincken, two years before his death. Bach also composed three versions of the chorale prelude "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" as part of the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes, the last dating from 1740–1750 in Leipzig, possibly as a tribute to Reincken's well-known chorale fantasia.

History and context

"An Wasserflüssen Babylon" is a Lutheran hymn written in 1525 and attributed to Wolfgang Dachstein, organist at St Thomas' Church, Strasbourg.[1][2][3] The hymn is a closely paraphrased versification of Psalm 137, "By the rivers of Babylon", a lamentation for Jerusalem, exiled in Babylon.[1][4] Its text and melody, Zahn number 7663, first appeared in Strasbourg in 1525 in Wolf Köpphel's Das dritt theil Straßburger kirchenampt.[1][5] This Strasbourg tract, which comprised the third part of the Lutheran service, is now lost.[5] Despite the lost tract from 1525, the Strasbourg hymn appeared in print in 1526 in Psalmen, Gebett und Kirchenordnung wie sie zu Straßburg gehalten werden and later.[5][6][7]

Wolfgang Egeloph Dachstein was born in 1487 in Offenburg in the Black Forest. In 1503 he became a fellow student with Martin Luther at the University of Erfurt. He entered the Dominican monastic order in around 1520 in Strasbourg, where he started a collaboration with Matthias Greiter, a friend and contemporary. Greiter was born in 1495 in Aichach, near Augsburg in Bavaria, where he attended a Latin school, before enrolling in theology at the University of Freiburg in 1510 and becoming a monk in Strasbourg in 1520.[8][9][10][11][12]

During the Reformation, Protestantism was adopted in Strasbourg in 1524. The reforms involved the introduction of the German vernacular, the use of Lutheran liturgy ("Gottesdienstordnung") and congregational singing. Both Greiter and Dachstein renounced their monastic vows and married in Alsace. Their association continued, with Greiter becoming a cantor in the Cathedral and Dachstein an organist at St Thomas. Both played an important role in the musical life of Strasbourg, with many contributions to Lutheran hymns and psalms. Daniel Specklin, a 16th-century architect from Alsace, where the region Dachstein takes its name, described in detail how the pair engaged in "das evangelium" and "vil gute psalmen". A costly edition of the Straßburger Gesangbuch was published by Köpphel in 1541, with a preface by the Lutheran reformer Martin Bucer: the title, text and psalm were printed in characteristic red and black with woodcuts by Hans Baldung. During the Counter-Reformation, however, the Augsburg Interim resulted in Strasbourg reinstating Catholicism in October 1549: both Dachstein and Greiter renounced Protestantism and Bucer was sent into exile in England, where under Edward VI he became Regius Professor of Divinity.[13][14][15]

Dachstein's hymn "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" was rapidly distributed—it was printed in Luther's 1545 Babstsches Gesangbuch[16]—and spread to most Lutheran hymnbooks by central Germany.[1] After the Sack of Magdeburg in 1631, during the Thirty Years' War, it was decreed that Dachstein's 137th Psalm would be sung every year as part of the ceremonies to commemorate the destruction of Magdeburg.[17]

The melody of the hymn became better known than its text, through the association of that melody with Paul Gerhardt's 17th-century Passion hymn "Ein Lämmlein geht und trägt die Schuld".[5][17] With that hymn text, the hymn tune of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" is adopted as EG 83 in the Protestant hymnal Evangelisches Gesangbuch.[18][19] The hymn tune is Dachstein's best known composition.[3]

Miles Coverdale provided an early English translation in the Tudor Protestant Hymnal "Ghostly Psalms and Spiritual Songs," 1539. These Lutheran versifications were written in continental Europe while Coverdale was in exile from England.[20][21][22]

Text

The Lutheran text of Dachstein first appeared in 1525.[1] The English translation by Miles Coverdale dates from 1539.[21][23]

|

German text |

English translation |

|

1. An Wasserflüssen Babylon, |

At the ryvers of Babilon, |

|

2. Die uns gefangen hielten lang |

They that toke us so cruelly, |

|

3. Wie sollen wir in solchem Zwang |

To whome we answered soberly: |

|

4. Ja, wenn ich nicht mit ganzem Fleiss, |

Yee, above all myrth and pastaunce, |

|

5. Die schnöde Tochter Babylon, |

O thou cite of Babilon, |

Hymn tune

Below is the 1525 hymn tune by Wolfgang Dachstein.

Musical settings

Vocal settings

There are several vocal works based on the hymn "An Wasserflüssen Babylon". In 1544 Georg Rhau composed two settings for several parts for his collection Neue Deutsche Geistliche Gesänge für die gemeinen Schulen.[25] Lupus Hellinck also set a 4-part setting in 1544, as part of his Newe deudsche geistliche Gesenge.[26] Benedictus Ducis wrote several settings in 3 and 4 parts of the hymn between 1541–1544.[27] Sigmund Hemmel used the text in the 1550s in his four-part setting, with the cantus firmus in the tenor: Der gantz Psalter Davids, wie derselbig in teutsche Gesang verfasse was printed in 1569.[28]

A native of Nuremberg, Hans Leo Hassler was taught by Andrea Gabrieli in Venice, where he excelled as a keyboard player and consorted with his younger uncle, Giovanni Gabrieli. Hassler's 4-part setting of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" was composed in 1608.[29]

Johann Hermann Schein composed a setting of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" for two sopranos and instrumental accompaniment, which he published in 1617.[30] His 1627 Cantional contained a four-part setting of the hymn, a setting which was republished by Vopelius's Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch (1682).[30][31][32][33] In 1628 Heinrich Schütz published a four-part harmonisation of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon", SWV 242, in the Psalmen Davids, hiebevorn in teutzsche Reimen gebracht, durch D. Cornelium Beckern, und an jetzo mit ein hundert und drey eigenen Melodeyen … gestellet, the Becker Psalter, Op. 5.[34][35] Samuel Scheidt, composed two settings of the hymn, SSWV 505 and 570, for soprano and organ in the Tabulatur-Buch hundert geistlicher Lieder und Psalmen of 1650.[36]

Franz Tunder composed a setting of the hymn for soprano, strings and continuo. Organist at the Marienkirche in Lübeck from 1646–1668, Tunder initiated his Abendmusik there. Buxtehude later married Tunder's daughter and succeeded him as organist at Lübeck.[37]

Bach also composed a number of four-part chorale harmonisations around 1735, including one setting of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon", BWV 276. The main copyist was Johann Ludwig Dietel, one of Bach's pupils from the Thomasschule zu Leipzig. Although considered to have been lost by Philipp Spitta, Dietel's manuscript (R.18)—containing one hundred and fifty chorales—was discovered recently in the Musikbibliothek der Stadt, Leipzig.[38][39][40]

Robin Leaver, the musicologist and theologian, has explained how to determine the key of a hymn tune from the text of an incipit: these apply to Bach's period and region. An example of Leaver's method is given from the 1736 Schemelli "Gesangbuch," taking "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" as the incipit: the key of G occurs 7 times and D once.[41][42]

The German composer of opera— Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor—and lieder, Otto Nicolai composed a 4-part setting of "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" in around 1832 as one of four songs in his op.17.[43]

Organ settings

The hymn also inspired seventeenth and early eighteenth century organ compositions in Northern Germany. Organ chorale preludes and free works by Johann Christoph Bach[44] (Johann Sebastian's first cousin once removed), Johann Adam Reincken[45], Johann Pachelbel[46] and Johann Sebastian Bach[47] have been based on "An Wasserflüssen Babylon".

The 17th-century musical style of the stylus phantasticus covers the freely composed organ and harpsichord/clavichord works, including dance suites. They lie within two traditions: those from northern Germany, primarily for organ using the whole range of manual and pedal techniques, with passages of virtuoso exuberance; and those from central Germany, primarily for string keyboards, which have a more subdued style. Buxtehude and Reincken are important exponents of the northern school and Pachelbel those from the centre.[48][49][50][51]

Johann Christoph Bach was born in Arnstadt in 1642 and was appointed organist at St George's, the principal church of Eisenach, from 1665. The 4-part chorale prelude "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" has the same kind of expressive dissonances, with suspensions, as his Lamento "Ach, daß ich Wassers gnug hätte" for voice and strings.[52]

Born probably in 1643, Reincken was the natural successor to Scheidemann as organist at the St. Catherine's Church, Hamburg, with his musical interests extending beyond the church to the Hamburg Opera and the collegium musicum: as remarked by the 18th-century musician Johann Gottfried Walther, his famous, dazzling and audacious chorale fantasia "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" probably marked that succession; its vast dimension of 327 bars and 10 chorale lines, some broken into two, encompass a wide range of techniques, such as its "motet-like development, figuration of the chorale in the soprano, fore-imitation in diminished note values, introduction of counter-motifs, virtuoso passage work, double pedals, fragmentation, and echo effects."[53][50][54][55]

Pachelbel was born in Nuremberg in Bavaria and spent some of his early years as a musician in Vienna before being appointed as organist in the Predigerkirche, Erfurt in 1679–1690: part of his duties involved an annual concert in June lasting half an hour. Pachelbel's repertoire contained eight different types of chorale preludes, the last of which formed a "hybrid combination-form", one which he particularly favoured. The chorales on "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" were all of that type: a concise four-part fugue followed by a 3-part setting accompanying a slow cantus firmus in the soprano or bass; or a 4-part setting with the soprano in the cantus firmus.[56]

Johann Sebastian Bach set the chorale prelude "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" as the third chorale of the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes, with two early settings from his period in Weimar (BWV 653a and BWV 653b) and a third reworking in Leipzig from 1740–1750, taken from the autograph manuscript of BWV 653.[57] The same melancholic sarabande-like music in the chorale prelude can be heard in Bach's closing movements of the monumental Passions: the increasing chromaticism and passing dissonances create a mood of pathos.[58] Bach's project for the Orgelbüchlein, dating from his period in Weimar, includes two blank manuscript pages for "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" (pages 116–117, Christian Life and Conduct) that were never set.[59]

-

BWV 653b, with a double pedal part (not necessarily by Bach)

-

Autograph manuscript of Bach's BWV 653

Bach and Reincken

Stinson's describes a concert in 1720, when Bach extemporised for "almost half an hour" on An Wasserflüssen Babylon at the organ loft of St. Catherine's Church, Hamburg, with a well-known comment of Reincken, written 2 years before his death: "I thought that this art was dead, but I see that in you it still lives."[60][61]

Bach wrote three versions of the third chorale of the "Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes". The coda of the last version, dating from his last decade in Leipzig, shares some compositional features of Reincken's chorale prelude: the ornamental descending flourish at the end of Reincken's coda

can be compared with Bach's closing coda of BWV 653 with scales in contrary motion in the lower manual and pedal.

As Stinson writes, "It is hard not to believe that this correspondence represents an act of homage." [62] Despite being composed in Leipzig within the traditions of Thuringia, however, Bach's contemplative "mesmerising" mood is far removed from his earlier improvisatory compositions in Hamburg and Reincken's chorale fantasia: the later chorale prelude is understated, with its cantus firmus subtly embellished.[63][64]

Reincken's extended chorale fantasia elaborates the hymn tune with a broad variety of techniques.[65] The young Johann Sebastian Bach owned a copy of this work when he studied with Georg Böhm in 1700. Bach's copy, in organ tablature, was rediscovered in 2005 at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar by Michael Maul and Peter Wollny. These scholars believe the tablature to be in Bach's hand, which is however doubted by Kirsten Beißwenger. If it is, it would be one of Bach's oldest extant manuscripts.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72]

Further reading

- Eduard Emil Koch: Geschichte des Kirchenlieds und Kirchengesangs der christlichen, insbesondere der deutschen evangelischen Kirche. Vol. 8: Zweiter Haupttheil: Die Lieder und Weisen. Stuttgart: Belser, 1876 (3rd edition), pp. 526–528. Template:Lang icon

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Leahy 2011, pp. 37–38, 53

- ^ Terry 1921, pp. 101–103

- ^ a b Julian 1907

- ^ Stinson 2001, p. 78

- ^ a b c d Zahn 1891

- ^ Zahn 1893, p. 7

- ^ Trocmé-Latter 2015, pp. 255–265

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 70–71

- ^ Brusniak 2001, pp. 121–122

- ^ Fornaçon, Siegfried 1957, p. 465

- ^ Müller, Hans-Christian 1966, pp. 41–42

- ^ Trocmé-Latter 2015, pp. 28–32, 90–96, 201

- ^ See:

- Weber 2001, pp. 70–71

- Brusniak 2001, pp. 121–122

- Fornaçon, Siegfried 1957, p. 465

- Müller, Hans-Christian 1966, pp. 41–42

- Trocmé-Latter 2015, pp. 28–32, 90–96, 201

- ^ Trocmé-Latter 2015, pp. 233–234

- ^ Hopf 1946, pp. 1–16

- ^ Krummacher 2001, pp. 194–195

- ^ a b Werner 2016, p. 205

- ^ Axmacher & Fischer 2002

- ^ "Ein Lämmlein geht und trägt die Schuld" (in German). Württembergische Landeskirche. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Coverdale 1846, pp. 571–572

- ^ a b Terry, Charles Sanford. "Bach's Chorals. Part III: The Hymns and Hymn Melodies of the Organ Works". oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Trocmé-Latter 2015, pp. 237–239

- ^ Coverdale 1846, pp. 571–572

- ^ Modernised orthography, while the original wording is found in Philipp Wackernagel: Das deutsche Kirchenlied von der ältesten Zeit bis zu Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts. Vol. III. Teubner, 1870, No. 135 (p. 98)

- ^ Mattfield, Victor H. (2001). "Rhau, Georg". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Blackburn, Bonnie J.. (2001). "Hellinck, Lupus". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Thomayer, Klaus (2001). "Ducis, Benedictus". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Brennecke, Wilfried (2001). "Hemmel, Sigmund". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Blankenberg, Walter; Panetta, Vincent J. (2001). "Hassler, Hans Leos". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ a b Snyder, Kerala J.; Johnston, Gregory J. (2001). "Schein, Johann Hermann". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Young, Percy M. (2001). "Vopelius, Gottfried". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Johann Hermann Schein (1627). Cantional, Oder Gesangbuch Augspurgischer Confession. Leipzig: Schein, pp. 325–327

- ^ Gottfried Vopelius (1682). Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch. Leipzig: Christoph Klinger, pp.706–709

- ^ Rifkin, Joshua; Linfield, Eva; McCulloch, Derek; Baron, Stephen (2001). "Schütz, Heinrich". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Schütz 2013

- ^ Snyder, Kerala J.; Bush, Douglas (2001). "Ducis, Benedictus". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Snyder, Kerala J. (2001). "Tunder, Franz". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^

See:

- Bach 1972, pp. 318–320

- Schulze 1983, pp. 81–84, 94–100

- Bach 1991

- Bach 1996

- Bach 1998, pp. 363–364

- Schulze 1996

- Dirst 2012, pp. 1–54

- Jerold 2014

- Leaver 2017, pp. 358–376

- ^ See:

- Melamed & Marissen 2006, pp. 124–126

- Tomita 2017, pp. 75

- Dirst 2017, pp. 469

- Leaver 2017, pp. 359

- ^ For the chronology of Bach's vocal works, see also:

- ^ Leaver 2014, pp. 15–33

- ^ Leaver 2017, p. 371

- ^ Konrad, Ulrich (2001). "Nicolai, Otto". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Rose 2017, pp. 228–229

- ^ Beißwenger 2017, pp. 243–244

- ^ Beißwenger 2017, p. 242

- ^ Williams 2003, pp. 347–351

- ^ Schulenberg 2003, p. 2003

- ^ Schulenberg 2006, pp. 34–36

- ^ a b Collins 2005, p. 119

- ^ Krummacher 1986, pp. 157–171

- ^ Rose 2017, pp. 203, 224–226

- ^ Apel 1972, pp. 605–606

- ^ *Grapenthin, Ulf (2001). "Reincken, Johann Adam". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ See also:

- ^ Butt 2004, pp. 199–200

- ^ Williams 2003, pp. 347–351

- ^ Stinson 2001, pp. 78–80

- ^ Stinson 1999, pp. 2–9

- ^ Bach 1998, p. 302

- ^ Stinson 2001, pp. 78–80

- ^ Stinson 2001, pp. 78–80

- ^ Geck 2006, pp. 507–509

- ^ Williams 2003, pp. 348–349

- ^ Shannon 2012, p. 207.

- ^ Adler, Margit (31 August 2006). "Earliest Music Manuscripts by Johann Sebastian Bach Discovered". www.klassik-stiftung.de. Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

- ^ Bach 2006

- ^ Stinson 2012

- ^ Williams 2016

- ^ Yearsley 2009

- ^ Beißwenger 2017

- ^ Rose 2017, pp. 226–227

References

- Apel, Willi (1972), The History of Keyboard Music to 1700, translated by Hans Tischler, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253211417

- Axmacher, Elke; Fischer, Michael (2002), "83 – Ein Lämmlein geht und trägt die Schuld", in Hahn, Gerhard; Henkys, Jürgen (eds.), Liederkunde zum Evangelischen Gesangbuch (in German), vol. 5, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 60–70, ISBN 978-3-52-550326-3

- Bach, J.S. (1972), "824. Breifen Kirnbergers an Breitkopf: Verhandlungen wegen der Neuausgabe von Bachs Chorälen, Berlin, 1.7.1777 bis 17.3.1779", in Schulze, Hans-Joachim (ed.), Dokumente zum Nachwirken Johann Sebastian Bachs 1750–1800, Johann Sebastian Bach. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke (NBA) (in German), vol. III [supplement], Bärenreiter, p. 318–320

- Bach, J.S. (1986), Bighley, Mark S. (ed.), The Lutheran Chorales in the Organ Works of J.S. Bach, Concordia Publishing House, ISBN 0570013356

- Bach, J.S. (1991), Rempp, Frieder (ed.), Choräle und geistliche Lieder. Teil 1, Repertoires der Zeit vor 1750 (score), Johann Sebastian Bach. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke (NBA) (in German), vol. III/2/1, Bärenreiter, p. 98

- Bach, J.S. (1996), Rempp, Frieder (ed.), Choräle und geistliche Lieder. Teil 2, Choräle der Sammlung C.P.E. Bach nach dem Druck von 1784-1787. 370 Choräle (critical commentary), Johann Sebastian Bach. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke (NBA) (in German), vol. III/2/2, Bärenreiter, pp. 124–125

- Bach, C.P.E. (1997), "236. To Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf, Hamburg, 27 December 1783", in Clark, Stephen L. (ed.), The Letters of C.P.E. Bach, translated by Stephen L. Clark, Oxford University Press, pp. 199–200, ISBN 9780198162384

- Bach, J.S. (1998), David, Hans T.; Mendel, Arthur; Wolff, Christoph (eds.), The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents, W.W. Norton, ISBN 0393319563

- Bach, J.S. (2006), Maul, Michael; Wollny, Peter (eds.), Weimarer Orgeltabulatur. Die frühesten Notenhandschriften Johann Sebastian Bachs sowie Abschriften seines Schülers Johann Martin Schubart. Mit Werken von Dietrich Buxtehude, Johann Adam Reinken und Johann Pachelbel, Documenta musicologica, Bärenreiter Facsimile, vol. II/39, translated by J. Bradford Robinson on pp. XXI-XXXIII, Bärenreiter, ISBN 9783761819579

- Beißwenger, Kirsten (2017), "Other Composers", in Leaver, Robin A. (ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, translated by Emerson Morgan, Taylor & Francis, p. 237–264, ISBN 9781409417903

- Brusniak, Friedhelm (2001), "Matthias Greiter", in Herbst, Wolfgang (ed.), Wer ist wer im Gesangbuch?, Handbuch Zum Evangelischen Gesangbuch (in German), vol. 2, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 121–122, ISBN 3525503237

- Butt, John (2004), "Germany and the Netherlands", in Silbiger, Alexander (ed.), Keyboard Music Before 1700 (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 140–221, ISBN 0415968917

- Collins, Paul (2005), The Stylus Phantasticus and Free Keyboard Music of the North German Baroque, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 9780754634164

- Coverdale, Miles (1846), "Ghostly Psalms and Spiritual Songs", in Pearson, George (ed.), Remains of Myles Coverdale, Parker Society, vol. 14, Cambridge University Press, pp. 571–572

- Dirst, Matthew (2012), "Inventing the Bach chorale", Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn, Musical Performance and Reception, Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–54, ISBN 0521651603

- Dirst, Matthew (2017), "Early Posthumous Published Editions", in Leaver, Robin A. (ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, Taylor & Francis, pp. 464–474, ISBN 9781409417903

- Dürr, Alfred (1957), "Zur Chronologie der Leipziger Vokalwerke J. S. Bachs", Bach-Jahrbuch (in German), 44: 5–162

- Dürr, Alfred (1976), Zur Chronologie der Leipziger Vokalwerke J. S. Bachs. Zweite Auflage: Mit Anmerkungen und Nachträgen versehener Nachdruck aus Bach-Jahrbuch (in German), Bärenreiter

- Fornaçon, Siegfried (1957), "Dachstein, Wolfgang", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 3, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 465–466; (full text online)

- Geck, Martin (2006), Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work, translated by John Hargraves, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0151006482

- Greschat, Martin (2004), "A Preacher in Strasbourg", Martin Bucer: A Reformer and His Times, translated by Stephen E. Buckwalter, Westminster John Knox Press, pp. 47–86, ISBN 0-664-22690-6

- Herl, Joseph (2008), "Strasbourg", Worship Wars in Early Lutheranism: Choir, Congregation and Three Centuries of Conflict, Oxford University Press, pp. 96–100, ISBN 0195365844

- Honders, Casper (1985), Over Bachs schouder... (in Dutch), Niemeijer, ISBN 9060623002

- Hopf, Constantin (1946), Martin Bucer and the English Reformation, Blackwells

- Jerold, Beverly (2012), "Johann Philipp Kirnberger versus Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg: A Reappraisal" (PDF), Dutch Journal of Music Theory: 91–108

- Jerold, Beverly (2013), "Johann Philipp Kirnberger and Authorship", Notes, 69, Music Library Association: 688–705

- Jerold, Beverly (2014), "Johann Philipp Kirnberger and the Bach Chorale Settings", Bach, 45, Riemenschneider Bach Institute: 34–43, JSTOR 43489889

- Julian, John (1907), A Dictionary of Hymnology, Dover Publications, pp. 277–278

- Krummacher, Friedhelm (1986), "Bach's Free Organ Works and the Stylus Phantasticus", in George Stauffer; Ernest May (eds.), J.S. Bach as Organist, Indiana University Press, pp. 157–171, ISBN 0713452625

- Krummacher, Christoph (2001), "Leipziger Gesangbuch 1545", in Herbst, Wolfgang (ed.), Wer ist wer im Gesangbuch?, Handbuch Zum Evangelischen Gesangbuch (in German), vol. 2, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 194–195, ISBN 3525503237

- Küster, Konrad (1996), "Musik an der Schwelle des Dreißigjährigen Krieges: Perspektiven der Psalmen Davids von Heinrich Schütz", Schütz-Jb, 18: 39–51

- Leahy, Anne (2011), "An Wasserflüssen Babylon", J. S. Bach's "Leipzig" Chorale Preludes: Music, Text, Theology, Contextual Bach Studies, vol. 3, Scarecrow Press, pp. 37–58, ISBN 0810881810

- Leaver, Robin A. (2014), "Letter Codes Relating to Pitch and Key for Chorale Melodies and Bach's Contributions to the Schemelli "Gesangbuch"", Bach, 45: 15–33, JSTOR 43489888

- Leaver, Robin A. (2017), "Chorales", in Leaver, Robin A. (ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, Taylor & Francis, pp. 358–376, ISBN 9781409417903

- Mattfield, Victor H. (2001). "Rhau, Georg". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Melamed, Daniel R.; Marissen, Michael (2006), "Four-part chorales", An Introduction to Bach Studies, Oxford University Press, pp. 124–126, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304923.001.0001/acprof-9780195304923-chapter-7 (inactive 2018-05-05), ISBN 9780195304923

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2018 (link) - Müller, Hans-Christian (1966), "Greiter, Matthäus", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 7, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 41–42; (full text online)

- Müller, Hans-Christian; Migliorini, Angela (2001). "Dachstein, Wolfgang". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Müller, Hans-Christian; Davies, Sarah (2001). "Greiter, Matthias". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Nolte, Ewald V.; Butt, John (2001). "Pachelbel, Johann". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Paisey, David; Bartrum, Giulia (2009), "Hans Holbein and Miles Coverdale: A New Woodcut", Print Quarterly, 26: 227–253, JSTOR 43826083

- Reincken, J.A. (2005), "Preface", in Dirksen, Pieter (ed.), Complete Organ Works, Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 7–10, 83, ISBN 9790004182291

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid group id (help) - Reincken, J.A. (2008), "Preface, Critical commentary, Facsimiles", in Beckmann, Klaus (ed.), Complete Organ Works (2nd ed.), Schott Music, pp. 9–12, 58–61, 61–64, ISMN 9790001137416

- Rifkin, Joshua; Linfield, Eva; McCulloch, Derek; Baron, Stephen (2001). "Schütz, Heinrich". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Rose, Steven (2017), "The Alt-Bachisches Archiv", in Leaver, Robin A. (ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, Taylor & Francis, p. 213–236, ISBN 9781409417903

- Schering, Arnold (1918), "Johann Philipp Kirnberger als Herausgeber Bachscher Choräle", Bach-Jahrbuch, 15: 141–149

- Schulenberg, David (2003), "Stylus Phantasticus", in Malcolm Boyd; John Butt (eds.), J.S. Bach, Oxford composer companions (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 471, ISBN 0198606206

- Schulenberg, David (2006), The keyboard music of J.S. Bach (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0415974003

- Schulze, Hans-Joachim (1983), "150 Stück von den Bachischen Erben", Bach-Jahrbuch (in German), 69: 81–100

- Schulze, Hans-Joachim (1996), "J.S. Bach's Vocal Works in the Breitkopf Nonthematic Catalogs of 1761 to 1836", in George B. Stauffer (ed.), J.S. Bach, the Breitkopfs, and Eighteenth-century Music Trade, Bach Perspectives, vol. 2, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 35–52, ISBN 0803210442

- Schütz, Heinrich (1628), "Der CXXXVII. Psalm", Psalmen Davids: Hiebevorn in Teutzsche Reimen gebracht durch D. Cornelium Beckern (in German), Freiberg: Georg Hoffman, pp. 560–564. RISM 00000990058712

{{citation}}: External link in|postscript=|postscript=at position 3 (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Schütz, Heinrich (2013), A Heinrich Schütz Reader: Letters and Documents in Translation, translated by Johnston, Gregory S., United States: Oxford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 0199812209

- Shannon, John R. (2012). The Evolution of Organ Music in the 17th Century: A Study of European Styles. McFarland. ISBN 9780786488667.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Snyder, Kerala Y.; Johnson, Gregory S. (2001). "Schein, Johann Hermann". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Spagnoli, Gina (1993), "Dresden at the Time of Heinrich Schütz", in Price, Curtis (ed.), The Early Baroque Era: From the late 16th century to the 1660s, Macmillan, pp. 164–184

- Stinson, Russell (1999), Bach: The Orgelbüchlein, Oxford University Press, pp. 2–9, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780193862142.001.0001/acprof-9780193862142-chapter-1 (inactive 2018-05-05), ISBN 9780193862142

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2018 (link) - Stinson, Russell (2001), J.S. Bach's Great Eighteen Organ Chorales, Oxford University Press, pp. 78–80, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195116663.001.0001/acprof-9780195116663-chapter-4 (inactive 2018-05-05), ISBN 0-19-516556-X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2018 (link) - Stinson, Russel (2012), J. S. Bach at His Royal Instrument: Essays on His Organ Works, Oxford University Press, p. 16, ISBN 019991723X

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1921), Bach's Chorals, vol. III, pp. 101–104

- Tomita, Yo (2017), "Manuscripts", in Leaver, Robin A. (ed.), The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach, Taylor & Francis, pp. 47–88, ISBN 9781409417903

- Trocmé-Latter, Daniel (2015), The Singing of the Strasbourg Protestants, 1523-1541, St Andrews Studies in Reformation History, Ashgate, ISBN 9781472432063

- Varwig, Bettina (2011), Histories of Heinrich Schütz, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1139502018

- Wachowski, Gerd (1983), "Die vierstimmungen Choräle Johann Sebastian Bachs. Untersuchungen zu den Druckausgaben von 1765 bis 1932 und zur Frage der Authenrizität", Bach-Jahrbuch (in German), 69: 51–80

- Weber, Édith (2001), "Wolfgang Dachstein", in Herbst, Wolfgang (ed.), Wer ist wer im Gesangbuch?, Handbuch Zum Evangelischen Gesangbuch (in German), vol. 2, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 70–71, ISBN 3525503237

- Werner, Wilfried (2016), "'Nicht mitzuhassen, mitzulieben bin ich da!' Exegese und Predigt zu Psalm 137", in Hartlapp, Johannes; Cramer, Andrea (eds.), "Und was ich noch sagen wollte ...": Festschrift für Wolfgang Kabus zum 80. Geburtstag (in German), Frank & Timme, pp. 193–216, ISBN 3732903133

- Williams, Peter (1980), The Organ Music of J.S. Bach, Volume II: BWV 599–771, etc., Cambridge Studies in Music, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31700-2

- Williams, Peter (2003), The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-89115-9

- Williams, Peter (2016), Bach: A Musical Biography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1107139252

- Wolff, Christoph (1986), "Johann Adam Reinken and Johann Sebastian Bach: On the Context of Bach's Early Works", in George Stauffer; Ernest May (eds.), J.S. Bach as Organist, Indiana University Press, pp. 57–80, ISBN 0713452625

- Yearsley, David (2009), "Bach Discoveries", Early Music, 37 (3): 489–492, doi:10.1093/em/cap055

- Yearsley, David (2012), Bach's Feet: The Organ Pedals in European Culture, Cambridge University Press, pp. 94–97, ISBN 1139500112

- Zahn, Johannes (1891), "7663", Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder (in German), vol. IV, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann, pp. 508–509

{{citation}}: External link in|volume= - Zahn, Johannes (1893), Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder (in German), vol. VI, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann

{{citation}}: External link in|volume=

External links

- An Wasserflüssen Babylon, Opella nova (Geistliche Konzerte, Leipzig, 1618) by Johann Hermann Schein: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- An Wasserflüssen Babylon, Becker Psalter, Op.5 (Psalmen Davids, Freiberg, 1628) by Heinrich Schütz: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- An Wasserflüssen Babylon, P.17, An Wasserflüssen Babylon, P.18, An Wasserflüssen Babylon, P.20 by Johann Pachelbel: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- An Wasserflüssen Babylon (Complete Organ Works, ed. Klaus Beckmann, Breitkopf & Härtel, 1974) by Johann Adam Reincken: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- An Wasserflüssen Babylon, BWV 267, BWV 653, by Johann Sebastian Bach: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Zu Fassungen der Melodie in Elsässischen Gesangbüchern colmarisches.free.fr

- Glebe, Karl ; Heinermann, Otto: / Vorspiele zum deutsch-evangelischen Gesangbuch für Orgel dzb.de

- G. W. Fink: No. 24 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, Volume 38, 1836

- "An Wasserflüssen Babylons". The Scroll Ensemble. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Dahn, Luke. "The Four-Part Chorales of J.S. Bach". Retrieved 9 April 2018.