Anomalocaris

| Anomalocaris Temporal range: Early to mid Cambrian:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Image of the first complete Anomalocaris fossil found, residing in the Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Dinocaridida |

| Order: | †Radiodonta |

| Family: | †Anomalocarididae |

| Genus: | †Anomalocaris Whiteaves 1892 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

(Defunct species:)[1]

| |

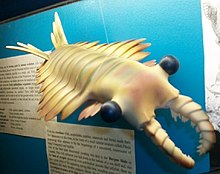

Anomalocaris ("abnormal shrimp") is an extinct genus of anomalocaridid, which are, in turn, thought to be closely related to the arthropods. The first fossils of Anomalocaris were discovered in the Ogygopsis Shale by Joseph Frederick Whiteaves, with more examples found by Charles Doolittle Walcott in the famed Burgess Shale.[2] Originally several fossilized parts discovered separately (the mouth, feeding appendages and tail) were thought to be three separate creatures, a misapprehension corrected by Harry B. Whittington and Derek Briggs in a 1985 journal article.[2][3]

Anatomy

Anomalocaris is thought to have been a predator. It propelled itself through the water by undulating the flexible lobes on the sides of its body.[4] Each lobe sloped below the one more posterior to it,[5] and this overlapping allowed the lobes on each side of the body to act as a single "fin", maximizing the swimming efficiency.[4] The construction of a remote-controlled model showed this mode of swimming to be intrinsically stable,[6] meaning that Anomalocaris need not have had a complex brain to cope with balancing while swimming. The widest part of the body was on the third to fifth lobe; it narrowed towards its tail, and had at least 11 lobes in total.[5] The more posterior lobes are difficult to discriminate, making an accurate count difficult.[5] Anomalocaris had a large head, a single pair of large, compound eyes on stalks comprising approximately 16,000 individual lenses,[7][8] and an unusual, disk-like mouth. The mouth was composed of 32 overlapping plates, four large and 28 small, resembling a pineapple ring with the center replaced by a series of serrated prongs.[2] The mouth could constrict to crush prey, but never completely close, and the tooth-like prongs continued down the walls of the gullet.[9] Two large 'arms' (up to seven inches in length when extended[9]) with barb-like spikes were positioned in front of the mouth.[3] The tail was large and fan-shaped, and along with undulations of the lobes, was probably used to propel the creature through Cambrian waters.[2][10][4] Stacked lamella of what were probably gills attached to the top of each lobe.

For the time in which it lived Anomalocaris was a truly gigantic creature, reaching lengths of up to two meters.[2]

Discovery

Anomalocaris has been misidentified several times, in part due to its makeup of a mixture of mineralized and unmineralized body parts; the mouth and feeding appendage was considerably harder and more easily fossilized than the delicate body.[9] Its name originates from a description of a detached 'arm', described by Joseph Frederick Whiteaves in 1892 as a separate crustacean-like creature due to its resemblance to the tail of a lobster or shrimp.[9] The first fossilized mouth was discovered by Charles Doolittle Walcott, who mistook it for a jellyfish and placed it in the genus Peytoia. Walcott also discovered a second feeding appendage but failed to realize the similarities to Whiteaves' discovery and instead identified it as feeding appendage or tail of the extinct Sidneyia.[9] The body was discovered separately and classified as a sponge in the genus Laggania; the mouth was found with the body, but was interpreted by its discoverer Simon Conway Morris as an unrelated Peytoia that had through happenstance settled and been preserved with Laggania. Later, while clearing what he thought was an unrelated specimen, Harry B. Whittington removed a layer of covering stone to discover the unequivocally connected arm thought to be a shrimp tail and mouth thought to be a jellyfish.[2][9] Whittington linked the two species, but it took several more years for researchers to realize that the continuously juxtaposed Peytoia, Laggania and feeding appendage actually represented a single, enormous creature.[9] According to International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature rules, the oldest name takes priority, which in this case would be Anomalocaris. The name Laggania was later used for another genus of anomalocarid. "Peytoia" has been modified into Parapeytoia, a genus of Chinese anomalocarid. Anomalocaris is placed in the extinct family Anomalocaridae, and is now considered to be related to modern arthropods.[citation needed]

Stephen Jay Gould cites Anomalocaris as one of the fossilized extinct species he believed to be evidence of a much more diverse set of phyla that existed in the Cambrian era[9] (discussed in his book Wonderful Life), a conclusion disputed by other paleontologists.[2]

Ecology

Anomalocaris had a cosmopolitan distribution in Cambrian seas, and has been found from early to mid Cambrian deposits from Canada, China, Utah and Australia, to name but a few.[6][11][12][13]

A long-standing view holds that Anomalocaris fed on hard-bodied animals, including trilobites. While its mid-gut glands strongly suggest a predatory lifestyle, its ability to penetrate mineralised shells has come under fire in recent years.[14] Some Cambrian trilobites have been found with round or W-shaped "bite" marks, which were identified in shape with the mouthparts of Anomalocaris.[12]

Stronger evidence that Anomalocaris ate trilobites comes from fossilised faecal pellets, which contain trilobite parts and are so large that the anomalocarids are the only organisms large enough to have produced them.[12] However, since Anomalocaris lacks any mineralised tissue, it seemed unlikely that it would be able to penetrate the hard, calcified shell of trilobites.[12] One possibility is that anomalocarids fed by grabbing one end of their prey in their jaws while using their appendages to quickly rock the other end of the animal back and forth. This produced stresses that exploited the weaknesses of arthropod cuticle, causing the prey's exoskeleton to rupture and allowing the predator to access its innards.[12] This behaviour is thought to have provided an evolutionary pressure for trilobites to roll up, to avoid being flexed until they snapped.[12] However, the lack of wear on anomalocarid mouthparts suggests they did not come into regular contact with mineralised trilobite shells. Computer modeling of the Anomalocaris mouthparts suggests they were in fact better suited to sucking on smaller, soft-bodied organisms (and could not have been responsible for many trilobite deformations).[14][15]

See also

- Anomalocarididae, the classification group of anomalocaris

- Cambrian explosion

- Opabinia

- Wiwaxia

Footnotes

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1666/09-136R1.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1666/09-136R1.1instead. - ^ a b c d e f g Conway Morris, S. (1998). The crucible of creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–9. ISBN 0-19-850256-7.

- ^ a b Whittington, H.B. (1985). "The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 309 (1141): 569–609. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.309..569W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Usami, Yoshiyuki (2006). "Theoretical study on the body form and swimming pattern of Anomalocaris based on hydrodynamic simulation". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 238 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.008. PMID 16002096.

- ^ a b c Whittington, H.B.; Briggs, D.E.G. (1985). "The Largest Cambrian Animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 309 (1141): 569–609. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.309..569W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0096.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Briggs, Derek E. G. (1994). "Giant Predators from the Cambrian of China". Science. 264 (5163): 1283–4. doi:10.1126/science.264.5163.1283. PMID 17780843. Cite error: The named reference "Briggs1994" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ John R. Paterson, Diego C. García-Bellido, Michael S. Y. Lee, Glenn A. Brock, James B. Jago & Gregory D. Edgecombe (2011). "Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes". Nature. 480 (7376): 237–240. doi:10.1038/nature10689.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ancient super-predator eyes found in Australia". Seven News. December 8, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gould, Stephen Jay (1989). Wonderful life: the Burgess Shale and the nature of history. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 194–206. ISBN 0-393-02705-8.

- ^ "The Anomalocaris homepage". Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Mount, J. D. (1982). "The Occurrence of the Giant Arthropod Anomalocaris in the Lower Cambrian of Southern California, and the Overall Distribution of the Genus". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (5): 1112–8. JSTOR 1304568.

- ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1130.2F0091-7613.281999.29027.3C0987:APONAM.3E2.3.CO.3B2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1130.2F0091-7613.281999.29027.3C0987:APONAM.3E2.3.CO.3B2instead. - ^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Robison, R. A. (1984). "Exceptionally preserved nontrilobite arthropods and Anomalocaris from the Middle Cambrian of Utah". University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions (111). ISSN 0075-5052.

- ^ a b Hagadorn, James W. (August 2009). "Taking a Bite out of Anomalocaris" (PDF). In Smith, Martin R.; O'Brien, Lorna J.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (eds.). Abstract Volume. International Conference on the Cambrian Explosion (Walcott 2009). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: The Burgess Shale Consortium (published 31 July 2009). ISBN 978-0-9812885-1-2.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra, "Fossil fangs not so fierce", Science News, Vol.178 #11 (p. 13). Online edition retrieved 2010.11.11

References

- Paul Chambers; Haines, Tim (2005). The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Buffalo, N.Y: Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55407-181-X. OCLC 85767395.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)