Arakan

Arakan (/ˈærəkæn/ ARR-ə-kan or /ˈɑːrəkɑːn/ AR-ə-kahn[1]) is a historic coastal country in Southeast Asia. Arakan was an independent kingdom for most of its history. It was also ruled by Indian kingdoms and Burmese Empires. Today, the territory forms the Rakhine State in Myanmar. The region is bordered by the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north and Burma proper to its east. The Arakan Mountains isolated the region from rest of Burma and once made Arakan accessible only by sea. Arakan has been the homeland of a multiethnic religiously diverse population, including Tibeto-Burman Arakanese Buddhists and Indo-Aryan Arakanese Indian Muslims and Hindus.

The Arabs traded with Arakan for two millennia. During the Age of Discovery, Arakan caught the interest of the Dutch East India Company and the Portuguese Empire. Arakan became a center of piracy and other areas of commerce. Arakan became one of the divisions of British India and later British Burma. Arakan Division was once a leading rice exporter. During the Second World War, the region was occupied by Imperial Japan. After Burmese independence, the renamed territory has seen ethnic conflict.

Etymology

Claudius Ptolemy identified Arakan as Argyré.[2] Portuguese records spelled the name as Arracao.[3] The name was spelled as Araccan in many old European maps and publications.[4] The region was named as Arakan Division during British rule in Burma.[5]

Other names

Early Arab traders were familiar with the Indian name of Rohang as the name of Arakan.[6] Burmese tradition holds the name of the region to be Rakhaing.[7]

History

Early inhabitants

It is unclear who the earliest inhabitants were; some historians believe the earliest settlers included the Burmese Mro tribe but there is a lack of evidence and no clear tradition of their origin or written records of their history.[8] Burmese traditional history holds that Arakan was inhabited by the Rakhine since 3000 BCE. But there is no archaeological evidence to support the claim.[9]: 17 According to British historian Daniel George Edward Hall, who wrote extensively on the history of Burma, "The Burmese do not seem to have settled in Arakan until possibly as late as the tenth century AD. Hence earlier dynasties are thought to have been Indian, ruling over a population similar to that of Bengal. All the capitals known to history have been in the north near modern Akyab".[10]

Indianization

Arakan became one of the earliest Indianized kingdoms in Southeast Asia. Arakan faced India across the sea. Arakan was the stepping stone for missionaries from the Mauryan Empire who traveled to Southeast Asia.[11][12]

First states

Due to the evidence of Sanskrit inscriptions found in the region, historians believe the founders of the first Arakanese state were Indian.[9]: 17 The first Arakanese state flourished in Dhanyawadi between the 4th and 6th centuries. The city was the center of a large trade network linked to India, China and Persia.[9]: 18 Power then shifted to the city of Waithali, where the Chandra dynasty ruled. Waithali became a wealthy trading port.[9]: 18 The Chandra-ruled Harikela state was known as the Kingdom of Ruhmi to the Arabs.[13]

Arrival of Islam

Since in the 8th century, Arab merchants began conducting missionary activities, and many locals converted to Islam.[14] Some researchers have speculated that Muslims used trade routes in the region to travel to India and China.[15] A southern branch of the Silk Road connected India, Burma and China since the neolithic period.[16][17] Many Arab merchants married local women and settled in Arakan. As a result of intermarriage and conversion, the Muslim population in Arakan grew.[18]

Rakhine migration

The Rakhine people were one of the tribes of the Burmese Pyu city-states. They began migrating to Arakan through the Arakan Mountains in the 9th century. The Rakhines settled in the valley of the Lemro River. Their cities included Sambawak I, Pyinsa, Parein, Hkrit, Sambawak II, Myohaung, Toungoo and Launggret. The cities flourished between the 11th and 15th centuries. The Burmese invaded Arakan in 1406.[9]: 18–20

Protectorate of Bengal

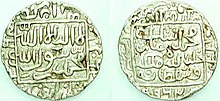

After the Burmese invasion, Min Saw Mon fled to Gaurh in the Bengal Sultanate, where he stayed in exile for 24 years after being granted asylum by Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah. In 1430, Min Saw Mon regained control of Arakan with help from the Bengal Sultanate. He established his new capital in the city of Mrauk U. Arakan became a vassal state of the Bengal Sultanate and recognized Bengali sovereignty over some territory of northern Arakan. Arakanese kings adopted Islamic titles and struck the Bengali taka. Min Saw Mon was styled as Suleiman Shah. Bengalis settled in Arakan and formed their settlements.[9]: 20 [19][20] The Santikan Mosque built in the 1430s.[19][21]

Kingdom of Mrauk U

Min Saw Mon's successors in the Kingdom of Mrauk U sought to end the Bengal Sultanate's hegemony. Min Khayi (Ali Khan) was the first to challenge Bengali hegemony. Ba Saw Phyu (Kalima Shah) defeated Bengal Sultan Rukunuddin Barbak Shah in 1459. Min Bin (Zabuk Shah) conquered Chittagong. Taking advantage of the Mughal Empire's invasion campaign of Bengal, the Arakan navy and pirates dominated a coastline of 1000 miles, spanning from the Sundarbans to Moulmein. The kingdom's coastline was frequented by Arab, Dutch, Danish and Portuguese traders. Control of the Kaladan River and Lemro River valleys led to increased international trade, making Mrauk U prosperous. The reigns of Min Phalaung (Sikender Shah), Min Rajagiri (Salim Shah I) and grandson Min Khamaung (Hussein Shah) strengthened the wealth and power of Mrauk U.[9]: 20–21 Arakan colluded in the slave trade with the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong. After conquering the port city of Syriam in the early 1600s, Arakan appointed the Portuguese mercenary Philip De Brito e Nicota as the governor of Syriam. But Nicota later transferred Syriam to the authority of Portuguese India.[9]: 21

Even after independence from the Sultans of Bengal, the Arakanese kings continued the custom of maintaining Muslim titles.[22] They compared themselves to Sultans and fashioned themselves after Mughal rulers. They also continued to employ Indians and Muslims in prestigious positions within the royal administration.[23] The court adopted Indian and Islamic fashions from neighbouring Bengal.[23][19] Mrauk U hosted mosques, temples, shrines, seminaries and libraries.[9]: 22 Syed Alaol was a renowned poet of Arakan.[24] Indian and Muslim influence continued on Arakanese affairs for 350 years.

In 1660, Shah Shuja, the brother of Emperor Aurangzeb and a claimant of the Peacock Throne, received asylum in Mrauk U. Members of Shuja's entourage were recruited in the Arakanese army and court. They were kingmakers in Arakan until the Burmese conquest.[25] Arakan suffered a major defeat to the forces of Mughal Bengal during the Battle of Chittagong in 1666, when Mrauk U lost control of southeast Bengal. The Mrauk U dynasty's reign continued until the 18th century.

Burmese conquest

The Konbaung Dynasty conquered Arakan in 1784. Mrauk U was devastated during the invasion.[9]: 22 The Burmese Empire executed thousands of men and deported a considerable portion of people from the Arakanese population to central Burma.[26]

British Empire

The Burmese Empire ceded Arakan to the British East India Company in the 1826 Treaty of Yandabo. Arakan became one of the divisions of British India. Initially governed as part of the Bengal Presidency, it became part of Burma Province, which was separated from India into a distinct crown colony in 1937. During World War II, Arakan endured the Japanese occupation of Burma. The Burma National Army and the pro-British V Force were active in the region. Sectarian tensions flared during the Arakan massacres in 1942. Japanese rule ended with the successful Burma Campaign by Allied forces.

During British rule, Arakan Division was one of the largest rice exporters in the world.[27] The division's seaport and capital Akyab were dominated by Arakanese Indians, which caused tension with Arakanese Burmese.[28] Both groups were represented as natives in the Legislative Council of Burma and the Legislature of Burma. In the 1940s, Arakanese Muslims appealed to Muhammad Ali Jinnah to incorporate the townships of the Mayu River valley into the Dominion of Pakistan.[29]

Burmese independence

Arakan became one of the Union of Burma's divisions after independence from British rule. Burma was a parliamentary democracy until the 1962 Burmese coup d'état. Arakan Division was eventually renamed as the Rakhine State. In 1982, the Burmese junta enacted the Burmese nationality law which did not recognize Arakanese Indians as one of Burma's ethnic groups, thereby stripping them of their citizenship.

Rakhine-led groups like the Arakan Liberation Army have sought independence for the region. Other groups, including the Arakan Rohingya National Organization, have demanded autonomy. The region witnessed military crackdowns during Operation King Dragon in 1978; in 1991 and 1992 after the 8888 uprising and Burmese general election, 1990; the 2012 Rakhine State riots, the 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis and Rohingya persecution in Myanmar (2016-present).

Geography

Arakan is a coastal geographic region in Lower Burma. It comprises a long narrow strip of land along the eastern seaboard of the Bay of Bengal and stretches from the Naf River estuary on the border of the Chittagong Hills area (in Bangladesh) in the north to the Gwa River in the south. The Arakan region is about 400 miles (640 km) long from north to south and is about 90 miles (145 km) wide at its broadest. The Arakan Mountains (also called Arakan Yoma), a range that forms the eastern boundary of the region, isolates Arakan from the rest of Burma. The coast has several sizable offshore islands, including Cheduba and Ramree. The region’s principal rivers are the Nāf estuary and the Mayu, Kaladan, and Lemro rivers. One-tenth of Arakan’s generally hilly land is cultivated. Rice is the dominant crop in the delta areas, where most of the population is concentrated. Other crops include fruits, chilies, dha and tobacco.[30]

The main towns are coastal and include Sittwe (Akyab), Sandoway, Kyaukpyu and Taungup.[30]

Demographics

The people of Arakan have historically been called the Arakanese. The population consists of Tibeto-Burmans and Indo-Aryans. Tibeto-Burman Arakanese speak an unusual variety of the Burmese language that includes significant differences from Burmese pronunciation and vocabulary. Indo-Aryan Arakanese speak the Rohingya language, an eastern Indo-Aryan language. The government of Myanmar recognizes Tibeto-Burman Arakanese as the Rakhine people. It is also recognizes sections of the Muslim community, including the Kamein. But Myanmar does not recognize Arakanese Indians who have campaigned under the term Rohingya.

Arakan Division had the largest percentage of Indians in British Burma.[31]

See also

References

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia, s.v. "Rakhine State".

- ^ Arthur Purves Phayre (1883). History of Burma. Рипол Классик. p. 42. ISBN 978-5-87742-763-1.

- ^ Frederick Charles Danvers (1988). The Portuguese in India: Being a History of the Rise and Decline of Their Eastern Empire. Asian Educational Services. p. 528. ISBN 978-81-206-0391-2.

- ^ Thomas Bankes; Edward Warren Blake; Alexander Cook; Thomas Lloyd (1800). A New, Royal, and Authentic System of Universal Geography, Antient and Modern: Including All the Late Important Discoveries ... and a Genuine History and Description of the Whole World ... Together with a Complete History of Every Empire, Kingdom, and State ... to which is Added a Complete Guide to Geography, Astronomy, the Use of the Globes, Maps ... p. 247.

- ^ Cheng Siok-Hwa (2012). The Rice Industry of Burma, 1852-1940: (First Reprint 2012). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 86. ISBN 978-981-230-439-1.

- ^ Abū al-Faz̤l ʻIzzatī; A. Ezzati (2002). The Spread of Islam: The Contributing Factors. ICAS Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-904063-01-8.

- ^ Arthur P. Phayre (17 June 2013). History of Burma: From the Earliest Time to the End of the First War with British India. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-136-39848-3.

- ^ Beniison, J.J (1933). Census of India, 1931: Burma Part I – Report. Rangoon: Office of Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Burma. p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j William J. Topich; Keith A. Leitich (9 January 2013). The History of Myanmar. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35725-1.

- ^ D. G. E Hall, A History of South East Asia, New York, 1968, P. 389.

- ^ British Academy (4 December 2003). Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 121, 2002 Lectures. OUP/British Academy. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-726303-7.

- ^ "Vaishali and the Indianization of Arakan - Noel F. Singer - Google Books". Books.google.com.bd. 1980-11-24. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ^ "Harikela - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ^ Sunil S. Amrith (7 October 2013). Crossing the Bay of Bengal. Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-674-72846-2.

- ^ "The thoroughfare of Islam - Dhaka Tribune". www.dhakatribune.com.

- ^ Foster Stockwell (30 December 2002). Westerners in China: A History of Exploration and Trade, Ancient Times through the Present. McFarland. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7864-8189-7.

- ^ Fuxi Gan (2009). Ancient Glass Research Along the Silk Road. World Scientific. p. 70. ISBN 978-981-283-357-0.

- ^ Andrew T. H. Tan (2009). A Handbook of Terrorism and Insurgency in Southeast Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 327.

- ^ a b c Aye Chan 2005, p. 398.

- ^ Yegar 2002, p. 23.

- ^ "Lost Myanmar Empire Is Stage for Modern Violence". National Geographic. June 26, 2015.

- ^ Yegar 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Yegar 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Francesca Orsini; Katherine Butler Schofield (5 October 2015). Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Open Book Publishers. p. 424. ISBN 978-1-78374-102-1.

- ^ Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman (19 June 2017). Islam and Peacebuilding in the Asia-Pacific. World Scientific. p. 24. ISBN 978-981-4749-83-1.

- ^ Aye Chan 2005, p. 399.

- ^ Georg Hartwig (1863). The Tropical World: a Popular Scientific Account of the Natural History of the Animal and Vegetable Kingdoms in the Equatorial Regions. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green. p. 159.

- ^ Christopher Alan Bayly; Timothy Norman Harper (2005). Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945. Harvard University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-674-01748-1.

- ^ Yegar 1972, p. 10.

- ^ a b Editors, The (1959-08-21). "Arakan | state, Myanmar". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Robert H. Taylor (1987). The State in Burma. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1-85065-028-7.

External links

Media related to Arakan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arakan at Wikimedia Commons