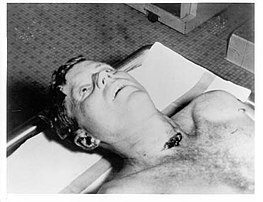

Autopsy of John F. Kennedy

The autopsy of John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was performed at the Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland. The autopsy began at about 8 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST) on November 22, 1963—the day of Kennedy's assassination—and ended in the early morning of November 23, 1963. The choice of autopsy hospital in the Washington, D.C. area was made by his widow, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who chose the Bethesda as President Kennedy had been a naval officer during World War II.[citation needed][1]

The autopsy was conducted by two physicians, Commander James Humes and Commander J. Thornton Boswell. They were assisted by ballistics wound expert Pierre Finck of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Although Kennedy's personal physician, Rear Admiral George Burkley pushed for an expedited autopsy simply to find the bullet, the commanding officer of the medical center—Admiral Calvin Galloway—intervened to order a complete autopsy.

The autopsy found that Kennedy was hit by two bullets. One entered his upper back and exited below his neck, albeit obscured by a tracheotomy. The other bullet struck Kennedy in the back of his head and exited the front of his skull in a large exit wound. The trajectory of the latter bullet was marked by bullet fragments throughout his brain. The former bullet was not found during the autopsy, but was discovered at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. It later became the subject of the Warren Commission's single-bullet theory, often derided as the "magic-bullet theory" by conspiracy theorists.

In 1968, U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark organized a medical panel to examine the autopsy's photographs and X-rays. The panel concurred with the Warren Commission's conclusion that Kennedy was killed by two shots from behind. The House Select Committee on Assassinations—which concluded that there likely was a conspiracy and that there had been an assassin in front of the president on the grassy knoll—also agreed with the Warren Commission. Nevertheless, due to procedural errors, discrepancies, and the 1966 disappearance of Kennedy's brain, the autopsy has become the subject of many conspiracy theories.

Background

[edit]

The 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, was assassinated on November 22, 1963, while driving in a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas.[2] Following the shooting, Kennedy's limousine brought him to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where he was pronounced dead.[3] The Secret Service was concerned about the possibility of a larger plot and urged the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, to leave Dallas and return to the White House. Johnson refused to do so without any proof of Kennedy's death.[4]

Johnson returned to Air Force One around 1:30 p.m., and shortly thereafter, he received telephone calls from advisors McGeorge Bundy and Walter Jenkins advising him to return to Washington, D.C. immediately.[5] He replied that he would not leave Dallas without the president's wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, and that she would not leave without Kennedy's body.[4][5] According to Esquire, Johnson did "not want to be remembered as an abandoner of beautiful widows".[5]

Dallas County medical examiner Earl Rose was at Parkland when he learned that President Kennedy had been pronounced dead.[6] Rose entered the trauma room where Kennedy's body lay and was confronted by Secret Service agent Roy Kellerman and Kennedy's personal physician George Burkley, who said that there was no time to perform an autopsy because Jacqueline Kennedy would not leave Dallas without her husband's body which was to be delivered promptly to the airport.[6]

At the time of President Kennedy's assassination, the murder of a president was not under the jurisdiction of any federal organization.[7] Accordingly, Rose insisted that Texas law required him to perform a post-mortem examination.[6][7] A heated exchange ensued as he argued with Kennedy's aides.[6][7] Kennedy's body was placed in a coffin and, accompanied by Jacqueline, rolled down the corridor on a gurney.[6] Rose was reported to have stood in a hospital doorway, backed by a Dallas policeman, in an attempt to prevent anybody from removing the coffin.[6][7] The presidential aides engaged in an explicit argument with Dallas officials until,[8][note 1] according to Robert Caro's The Years of Lyndon Johnson, they "literally shoved [Rose] and the policeman aside to get out of the building".[6] Rose later stated that he had not fought back as he felt it unwise to escalate tensions further.[6]

Autopsy

[edit]Site selection

[edit]

Kennedy's aides disagreed as to where the autopsy should be conducted. Kennedy's personal physician, Rear Admiral George Burkley pushed for Bethesda Naval Hospital.[9] However, Major General Ted Clifton instructed Surgeon General Leonard D. Heaton that it would be conducted at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.[9][10] General Godfrey McHugh ordered an ambulance to transport Kennedy's body to Walter Reed. When informed that it was illegal to do so in D.C. without a coroner's permission, McHugh offered to pay the fine.[11]

Burkley then consulted with Jacqueline, who was initially reluctant to have an autopsy.[11] She selected Bethesda Naval Hospital as President Kennedy had been a naval officer during World War II.[11][12] She chose Secret Service Agent William Greer—who she felt sorry for as he faulted himself for not saving the president—to drive Kennedy's casket to Bethesda.[11] As the body was transported from Andrews Air Force Base to Bethesda, crowds of mourners lined the roads.[13]

Navy Surgeon General Edward C. Kenney ordered two naval medical doctors, Commander James Humes and Commander J. Thornton Boswell, to conduct the autopsy.[14] Humes was selected as lead surgeon. Boswell called the decision to conduct the autopsy at Bethesda "stupid" and argued that it should instead be held at the specialized Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) just five miles away. Although both had conducted autopsies, neither were trained or certified in forensic pathology.[15][note 2]

Post-mortem at Bethesda

[edit]At 7:35 pm EST on November 22, Humes and Boswell removed Kennedy's body from his bronze casket and began the autopsy.[17] Around two dozen people, including military officers, were in attendance.[18][note 3] Admiral Burkley urged the doctors to expedite the autopsy: "all we need is the bullet". Drs. Humes and Boswell, however, argued for a thorough and complete autopsy but temporarily submitted.[24] Medical personnel took photographs—both black and white and color—and X-rays of his head.[24]

The X-rays revealed around 40 small bullet fragments along the bullet's trajectory through Kennedy's head, with two large enough to be of interest to investigators. Drs. Humes and Boswell then contacted wound ballistics expert Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Finck of AFIP for assistance.[25] However, they grew tired of waiting and removed the two fragments.[26] They also extracted Kennedy's entire brain and placed it into formaldehyde for later study. Finck arrived soon thereafter and examined the head wound with Boswell and Humes.[27]

Kennedy's body was then turned onto its side to examine the other wound. The three identified an entry point in Kennedy's back but were unable to find the corresponding exit wound or the bullet upon initial probing. Finck argued for a complete radiological survey of the body, and Humes suggested they conduct a complete autopsy. This angered Burkley, who argued that Jacqueline only wanted a limited autopsy. Admiral Calvin Galloway—the commanding officer of the US Naval Medical Center—overruled Burkley and ordered the doctors to carry out an entire autopsy.[28][note 4] After further examination and the full-body X-rays, no bullet or major fragment was recovered from Kennedy's body.[30] The physicians were puzzled, and observers suggested various hypotheses—the projectile was a soft-point bullet, made of plastic or ice—until an FBI agent informed the physicians that a bullet had just been found at Parkland.[31]

After midnight, three skull fragments discovered by the Secret Service were brought to the pathologists.[32] They noted the largest fragment had what appeared to be an exit wound, confirmed when X-rays found metal fragments.[33] After completing the autopsy after midnight, Humes informed the waiting FBI agents that Kennedy had been hit by two bullets from behind, to the back and to the head. He concluded that the latter bullet had been fatal, and that the former had "worked its way out of the body during cardiac massage at Parkland".[34]

Death certificates

[edit]Burkley signed a death certificate on November 23 and noted that the cause of death was a gunshot wound to the skull.[35][36] He described the fatal head wound as something "shattering in type causing a fragmentation of the skull and evulsion of three particles of the skull at time of the impact, with resulting maceration of the right hemisphere of the brain."[36] He also noted "a second wound occurred in the posterior back at about the level of the third thoracic vertebra".[36] [citation needed][37] A second certificate of death, signed on December 6 by Theron Ward, a Justice of the Peace in Dallas County, stated that Kennedy died "as a result of two gunshot wounds (1) near the center of the body and just above the right shoulder, and (2) 1 inch to the right center of the back of the head."[38]

Official findings

[edit]The gunshot wound in the back

[edit]- The Bethesda autopsy physicians attempted to probe the bullet hole in the base of Kennedy's neck above the scapula, but failed as it had passed through neck strap muscle. They did not perform a full dissection or persist in tracking, as throughout the autopsy they were unaware of the exit wound at the front of the throat. Emergency room physicians had obscured it while performing the tracheotomy.

- At Bethesda, the autopsy report of the president, Warren Exhibit CE 387,[39] described the back wound as being oval-shaped, 6 by 4 millimeters (0.24 in × 0.16 in), and located "above the upper border of the scapula" (shoulder blade) at a location 14 centimeters (5.5 in) from the tip of the right acromion process, and 14 centimeters (5.5 in) below the right mastoid process (the bony prominence behind the ear).

- The concluding page of the Bethesda autopsy report[39] states that "[t]he other missile [the bullet to the back] entered the right superior posterior thorax above the scapula, and traversed the soft tissues of the supra-scapular and the supra-clavicular portions of the base of the right side of the neck."

- The report also said that there was contusion (i.e., a bruise) of the apex (top tip) of the right lung in the region where it rises above the clavicle, and noted that although the apex of the right lung and the parietal pleural membrane over it had been bruised, they were not penetrated. This indicated passage of a missile close to them, but above them. The report pointed out that the thoracic cavity was not penetrated.

- This bullet produced contusions both of the right apical parietal pleura and of the apical portion of the right upper lobe of the lung. The bullet contused the strap muscles of the right side of the neck, damaged the trachea, and exited through the anterior surface of the neck.

- The single bullet theory of the Warren Commission Report places a bullet wound at the sixth cervical vertebra (C6) of the vertebral column, which is consistent with 5.5 inches (14 cm) below the ear. The Warren Report itself does not conclude bullet entry at the sixth cervical vertebra, but this conclusion was made in a 1979 report on the assassination by the HSCA, which noted a defect in the C6 vertebra in the Bethesda X-rays, which the Bethesda autopsy physicians had missed and did not note. The X-rays were taken by US Navy Medical Corps Commander John H. Ebersole.

Even without any of this information, the original Bethesda autopsy report, included in the Warren Commission report, concluded that this bullet had passed entirely through the President's neck, from a level over the top of the scapula and lung (and the parietal pleura over the top of the lung) and through the lower throat.

The gunshot wound to the head

[edit]- The gunshot wound to the back of the president's head was described by the Bethesda autopsy as a laceration measuring 15 by 6 millimetres (0.59 in × 0.24 in), situated to the right and slightly above the external occipital protuberance. In the underlying bone is a corresponding wound through the skull showing beveling (a cone-shaped widening) of the margins of the bone as viewed from the inside of the skull.[40]

- The large and irregularly-shaped wound in the right side of the head (chiefly to the parietal bone, but also involving the temporal and occipital bone) is described as being about 13 centimetres (5.1 in) wide at the largest diameter.[40]

- Three skull bone fragments were received as separate specimens, roughly corresponding to the dimensions of the large defect. In the largest of the fragments is a portion of the perimeter of a roughly circular wound presumably of exit, exhibiting beveling of the exterior of the bone, and measuring about 2.5 to 3.0 centimetres (0.98 to 1.18 in). X-rays revealed minute particles of metal in the bone at this margin.[40]

- Minute fragments of the projectile were found by X-ray along a path from the rear wound to the parietal area defect.[41]

Later government investigations

[edit]Ramsey Clark Panel

[edit]

In 1968, U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark appointed a panel of four medical experts to examine photographs and X-rays from the autopsy.[42] The panel confirmed findings that the Warren Commission had published: the President was shot from behind and was hit by only two bullets. The summary by the panel stated: "Examination of the clothing and of the photographs and X-rays taken at [the] autopsy reveal that President Kennedy was struck by two bullets fired from above and behind him, one of which traversed the base of the neck on the right side without striking bone and the other of which entered the skull from behind and exploded its right side."[43]

Rockefeller Commission (1975)

[edit]The five-member Rockefeller Commission, which included three pathologists, a radiologist, and a wound ballistics expert, did not address the back and throat wounds, writing in its report that "[t]he investigation was limited to determining whether there was any credible evidence pointing to CIA involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy," and that "the witnesses who had presented evidence believed sufficient to implicate the CIA in the assassination of President Kennedy placed too much stress upon the movements of the President's body associated with the head wound that killed the President."

The Commission examined the Zapruder, Muchmore, and Nix films; the 1963 autopsy report, the autopsy photographs and X-rays, President Kennedy's clothing and back brace, the bullet and bullet fragments recovered, the 1968 Clark Panel report, and other materials. The five panel members came to the unanimous conclusion that: President Kennedy had been hit by only two bullets, both of which were fired from the rear, including one that hit the back of the head. Three of the physicians reported that the backward and leftward motion of the President's upper body following the head shot was caused by a "violent straightening and stiffening of the entire body as a result of a seizure-like neuromuscular reaction to major damage inflicted to nerve centers in the brain."

The report added that there was “NO evidence to support the claim that President Kennedy was struck by a bullet fired from either the grassy knoll or any other position to his front, right front, or right side … No witness who urged the view [before the Rockefeller Commission] that the Zapruder film and other motion picture films proved that President Kennedy was struck by a bullet fired from his right front was shown to possess any professional or other special qualifications on the subject” ."[44]

HSCA (1979)

[edit]Where bungled autopsies are concerned, President Kennedy's is the exemplar.

The United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) contained a forensic pathology panel—often simply described as the medical panel—that undertook the unique task of reviewing original autopsy photographs and X-rays and interviewed autopsy personnel, as to their authenticity.[46][citation needed][47] The Panel and HSCA then went on to make some medical conclusions based on this evidence. The committee's forensic pathology panel included nine members, eight of whom were chief medical examiners in major local jurisdictions in the United States. As a group, they were responsible for over 100,000 autopsies, an accumulation of experience that the committee deemed invaluable in the medical evidence evaluation — including the autopsy X-rays and photographs — to determine the cause of the President's death as well as the nature and locations of his wounds.[citation needed]

The HSCA forensic pathology panel concluded that the autopsy had "extensive failings" and that the pathologists made multiple procedural errors, as following:[48]

- Failing to confer with the Parkland doctors prior to the autopsy

- Failing to examine clothing, which could have indicated trajectories

- Failing to determine the exact exit point of the head bullet

- Failing to dissect the back and neck

- Failing to determine the angles of gunshot injuries relative to body axis

- Failing to take proper and sufficient photographs

- Failing to properly examine the brain

The forensic panel concluded that the three pathologists were not qualified to conduct a forensic autopsy. Panel member Milton Helpern, Chief Medical Examiner for New York City, went so far as to say that selecting Humes (who had only taken a single course on forensic pathology) to lead the autopsy was "like sending a seven-year-old boy who has taken three lessons on the violin over to the New York Philharmonic and expecting him to perform a Tchaikovsky symphony".[49]

The committee also employed experts to authenticate the autopsy materials. Neither the Clark Panel nor the Rockefeller Commission undertook to determine if the X-rays and photographs were, in fact, authentic. Considering the numerous issues that had arisen over the years with respect to autopsy X-rays and photographs, the committee believed that authentication was a crucial step in the investigation. The authentication of the autopsy X-rays and photographs was accomplished by the committee assisting its photographic evidence panel as well as forensic dentists, forensic anthropologists, and radiologists working for the committee. Two questions were put to these experts:

- Could the photographs and X-rays stored in the National Archives be positively identified as being of President Kennedy?

- Was there any evidence that any of these photographs or X-rays had been altered in any manner?

To determine if the photographs of the autopsy subject were actually of the President, forensic anthropologists compared the autopsy photographs with ante-mortem pictures of him. This comparison was done based on both metric and morphological features. The metric analysis relied on various facial measurements taken from the photographs. The morphological analysis dealt with the consistency of physical features, particularly those that could be considered distinctive, such as the shape of the nose and patterns of facial lines (i.e. once unique characteristics were identified, posterior and anterior autopsy photographs were compared to verify that they depicted the same person).

The anthropologists studied the autopsy X-rays together with premortem X-rays of the President. A sufficient number of unique anatomic characteristics were present in X-rays taken before and after the President's death to conclude that the autopsy X-rays were of President Kennedy. This conclusion was consistent with the findings of a forensic dentist employed by the committee. Since many of the X-rays taken during the course of the autopsy included Kennedy's teeth, it was possible to determine, using his dental records, that the X-rays were of the President.

As soon as the forensic dentist and anthropologists had determined that the autopsy photographs and X-rays were of the President, photographic scientists and radiologists examined the original autopsy photographs, negatives, transparencies, and X-rays for signs of alteration. They concluded that there was no evidence of the photographic or radiographic materials having been altered, so the committee determined that the autopsy X-rays and photographs were a valid basis for the conclusions of the committee's forensic pathology panel.

While the examination of the autopsy X-rays and photographs was mainly based on its analysis, the forensic pathology panel also had access to all relevant witness testimony. Furthermore, all tests and evidence analyses requested by the panel were performed. It was only after considering all of this evidence that the panel reached its conclusions.

The pathology panel concluded that President Kennedy was struck by only two bullets, each of which had been shot from behind. The panel also concluded that the President was struck by "one bullet that entered in the upper right of the back and exited from the front of [his] throat, and one bullet that entered in the right rear of [his] head near the cowlick area and exited from the right side of the head, toward the front" saying that "this second bullet caused a massive wound to the President's head upon exit." The panel concluded that there was no medical evidence that the President was struck by a bullet entering the front of the head; and the possibility of such a bullet having struck him and yet left no physical evidence was extremely remote.

Because this conclusion appeared to be inconsistent with the backward motion of the President's head in the Zapruder film, the committee consulted a wound ballistics expert to determine what relationship, if any, exists between the direction from which a bullet strikes the head and the subsequent head movement. The expert concluded that nerve damage caused by a bullet entering the President's head could have caused his back muscles to tighten, which could have forced his head to move toward the rear. He demonstrated the phenomenon in a filmed experiment involving the shootings of goats. Therefore, the committee determined that the rearward movement of the President's head would not have been fundamentally inconsistent with a bullet striking from the rear.[50]

The HSCA also voiced certain criticisms of the original Bethesda autopsy and handling of evidence from it. These included:

- the "entrance head wound location was incorrectly described."

- The autopsy report was "incomplete", prepared without reference to the photographs, and was "inaccurate" in a number of areas, including the entry in Kennedy's back.

- The "entrance and exit wounds on the back and front neck were not localized with reference to fixed body landmarks and to each other".

The HSCA's major medical-forensic conclusion was that "President Kennedy was struck by two rifle shots fired from behind him."[51] The committee found acoustic evidence of a second shooter, but concluded that this shooter did not contribute to the president's wounds, and therefore was irrelevant to the autopsy results.[citation needed] Cyril Wecht—described by Bugliosi as the most "prominent medical critic of the Warren Commission"—was a frequent dissenter on the nine-member of the HSCA's medical panel and rejected the Warren Commission's single-bullet theory. He concurred with the other pathologists that Kennedy was hit in the head and upper back and that both shots came from behind.[52]

Wecht has argued that Kennedy may have been hit by two other shots. He has argued that the throat wound is more indicative of an entry wound than an exit wound. Wecht has suggested that Kennedy's head may have been hit by two nearly simultaneous shots, one from the rear and one from the front.[53]

Document inventory analysis: Assassination Records Review Board (1992–98)

[edit]The Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) was created by the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, which mandated the gathering and opening of all US government records related to the assassination.[54] The ARRB began work in 1994 and produced a final report in 1998.[55] The Board partially credited public concern about conclusions in the 1991 Oliver Stone movie JFK for passage of the legislation that developed the ARRB. The Board noted that the movie had "popularized a version of President Kennedy's assassination that featured U.S. government agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the military as conspirators."[56]

According to Douglas P. Horne, the ARRB's chief analyst for military records,

The Review Board's charter was simply to locate and declassify assassination records, and to ensure they were placed in the new "JFK Records Collection" in the National Archives, where they would be freely available to the public. Although Congress did not want the ARRB to reinvestigate the assassination of President Kennedy, or to draw conclusions about the assassination, the staff did hope to make a contribution to future 'clarification' of the medical evidence in the assassination by conducting these neutral, non-adversarial, fact-finding depositions. All of our deposition transcripts, as well as our written reports of numerous interviews we conducted with medical witnesses, are now a part of that same collection of records open to the public. Because of the Review Board's strictly neutral role in this process, all of these materials were placed in the JFK Collection without comment.[57]

The ARRB sought additional witnesses in an attempt to compile a more complete record of Kennedy's autopsy.[58] In July 1998, a staff report released by the ARRB emphasized shortcomings in the original autopsy.[58] The ARRB wrote, "One of the many tragedies of the assassination of President Kennedy has been the incompleteness of the autopsy record and the suspicion caused by the shroud of secrecy that has surrounded the records that do exist."[58]

A staff report for the Assassinations Records Review Board contended that brain photographs in the Kennedy records are not of Kennedy's brain and show much less damage than Kennedy sustained. Boswell refuted these allegations.[59] The Board also found that, conflicting with the photographic images showing no such defect, a number of witnesses, including at both the Autopsy and Parkland hospital, saw a large wound in the back of the president's head.[60] The Board and board member, Jeremy Gunn, have also stressed the problems with witness testimony, asking people to weigh all of the evidence, with due concern for human error, rather than take single statements as "proof" for one theory or another.[61][62]

Speculation and conspiracy theories

[edit]

Most historians regard the autopsy as the "most botched" segment of the government's investigation.[45]

In 1966, Kennedy's brain was found to be missing from the National Archives. Conspiracy theorists often claim that the brain may have shown a bullet from the front. It has also been suggested that Robert Kennedy destroyed the brain. Historian James Swanson theorized that he may have done so to "conceal evidence of the true extent of President Kennedy's illnesses, or perhaps to conceal evidence of the number of medications that President Kennedy was taking".[63]

Conspiracy theorists often allege that the autopsy was controlled by the military. During the 1969 trial of Clay Shaw for conspiring to assassinate Kennedy, pathologist Finck testified that when Humes asked "Who is in charge here?" an unknown army general stepped forward and said he was. However, Bugliosi notes that Finck was only referring to the "over-all" operations of the autopsy.[64]

According to Humes, he "destroyed by burning certain preliminary draft notes" about the autopsy. Mark Lane claimed that this was destruction of evidence.[65] In a 1992 interview with JAMA, Humes explained that he had already transcribed them and, as they were splattered with Kennedy's blood, did not wish for them to become a collector's item.[16]

In 1980, David Lifton's Best Evidence was published by Macmillan. It was met with critical praise, made The New York Times Best Seller list, and was selected for the Book of the Month Club.[66] In it, Lifton argues that Kennedy's body was tampered and altered to support the appearance of a single shooter before it arrived at Bethesda.[67] Vincent Bugliosi noted that it may be the most "preposterous" conspiracy theory relating to the assassination.[67]

Lifton's strongest piece of evidence, according to Bugliosi, is a November 26, 1963 FBI memo that describes Kennedy's body as having had "surgery of the head area, namely in the top of the skull" before the autopsy.[68] Former FBI agent James W. Sibbert stated in 1999 that this claim originated from Humes, who said it upon first seeing Kennedy's body.[69]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The newly-arrived justice of the peace for the 3rd Precinct of Dallas, Theron Ward, explained to the presidential aides that it was his duty to order an autopsy in Dallas. When Kennedy's aides argued that he deserved a federal autopsy, Ward answered, "It's just another homicide case as far as I'm concerned." Presidential aide Kenneth O'Donnell yelled in response, "Go fuck yourself!"[8]

- ^ In a 1992 interview with JAMA, Drs. Humes and Boswell stated they had conducted "several" autopsies on soldiers killed by gunfire.[16]

- ^ Following is a list of personnel present at various times during the autopsy, with official function, taken from the Sibert-O'Neill report list, the HSCA list[19] and attorney Vincent Bugliosi, author of Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The following were official autopsy signatories[20] Commander J. Thornton Boswell, M.D., MC, USN (Chief of pathology at Naval Medical Center, Bethesda), Commander James J. Humes, M.D., MC, USN (Director of laboratories of the National Medical School, Naval Medical Center, Bethesda. Chief autopsy pathologist for the JFK autopsy. Officially conducted autopsy.), Lieutenant Colonel Pierre A. Finck, M.D. MC, USA (Chief of the military environmental pathology division and chief of the wound ballistics pathology branch at Walter Reed Medical Center). Other medical personnel present included: John Thomas Stringer, Jr (medical photographer), Floyd Albert Riebe (medical photographer), PO Raymond Oswald, USN (medical photographer on call), Paul Kelly O'Connor (laboratory technologist), James Curtis Jenkins (laboratory technologist), Edward F. Reed (X-ray technician), Jerrol F. Custer (X-ray technician), Jan Gail Rudnicki (Boswell's lab tech assistant on the night of the autopsy), PO James E. Metzler, USN (Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class), John H. Ebersole (Assistant Chief of Radiology), Lieutenant Commander Gregory H. Cross, M.D., MC, USN (resident in surgery), Lieutenant Commander Donald L. Kelley, M.D., MC, USN (resident in surgery), CPO Chester H. Boyers, USN (Chief petty officer in charge of the pathology division, visited the autopsy room during the final stages to type receipts given by FBI and Secret Service for items obtained), Vice Admiral Edward C. Kenney, M.D.,MC, (USN: Surgeon general of the U.S. Navy), George Bakeman, USN, Rear Admiral George Burkley, M.D., MC, USN: (the president's personal physician), Captain James M. Young, M.D., MC, USN (the attending physician to the White House), Robert Frederick Karnei, M.D. (Bethesda pathologist), Captain David P. Osborne, M.D., MC, USN (chief of surgery at Bethesda), and Captain Robert O. Canada, M.D., USN (Commanding officer of Bethesda Naval Hospital). Non-medical personnel from law-enforcement and security included John J. O'Leary (Secret Service), William Greer (Secret Service), Roy Kellerman (Secret Service), Francis X. O'Neill (FBI special agent), and James "Jim" Sibert (FBI special agent, assisting Francis O'Neill).[21] The two FBI agents were to take custody of any bullets removed from Kennedy's body and bring them to the FBI laboratory.[22] Additional military personnel included Brigadier General Godfrey McHugh, USAF (US military aide to the President on the Dallas trip), Rear Admiral Calvin B. Galloway, USN (Commanding officer of the U.S. Naval Medical Center, Bethesda), Captain John H. Stover, Jr., USN (Commanding officer of the U.S. Naval Medical School, Bethesda), Major General Philip C. Wehle, USA (Commanding officer of the U.S. Military District of Washington, D.C., entered to make arrangements for the funeral and lying in state), 2nd Lieutenant Richard A. Lipsey, USA: Jr. (aide to General Wehle),[23] 1st Lieutenant Samuel A. Bird, USA: Head of the Old Guard, and SCPO, Alexander Wadas (Chief on duty). After the conclusion of the autopsy, the following personnel from Gawler's Funeral Home in Washington, D.C. entered the autopsy room to prepare the President's body for viewing and burial, which required 3 to 4 hours: John Van Hoesen, Edwin Stroble, Thomas E. Robinson, and Joe Hagen.[23]

- ^ During the autopsy, the pathologists could not identify any adrenal tissue, confirming the then-rumor that the president suffered from Addison's disease.[29]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Trek London (23 January 2023). "Why J.F.K's Widow Chose Bethesda as his Autopsy Hospital". TrekLondon UK. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. xi, xxii, xlii.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. xi.

- ^ a b Boyd (2015), pp. 59, 62.

- ^ a b c Jones, Chris (September 16, 2013). "The Flight from Dallas". Esquire. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stafford, Ned (July 13, 2012). "Earl Rose: Pathologist prevented from performing autopsy on US President John F Kennedy" (PDF). BMJ. 345. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4768. S2CID 220100505. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Munson, Kyle (April 28, 2012). "Munson: Iowan more than a footnote in JFK lore". The Des Moines Register. Indianapolis. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), pp. 110.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), pp. 137-138.

- ^ Howe, Marvine (December 28, 1991). "Gen. Chester Clifton Jr., 78, Dies; Was Military Aide to 2 Presidents". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Bugliosi (2007), p. 138.

- ^ Warren Report (2004) [1964] , p. 18.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 145-146.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 139-140.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 140.

- ^ a b Altman, Lawrence K. (May 24, 1992). "May 17–23: J. F. K. Autopsy; After 29 Years of Silence, The Pathologists Speak Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 149.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 149-150.

- ^ "Section II - Performance of Autopsy". Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ^ Warren Commission Report, Appendix 9. "Autopsy Report and Supplemental Report" (PDF). The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Miller, Glenn (November 22, 2009). "Ex-FBI agent who watched JFK autopsy reflects on death". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 146.

- ^ a b "HSCA INTERVIEW WITH RICHARD LIPSEY, 1-18-78". History-matters.com. 1939-10-07. Archived from the original on 2013-11-25. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 150.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 152.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 156-157.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 157.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 162.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 388.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 157, 170.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 171.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 180.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 180-181.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 181.

- ^ WGBH Educational Foundation. "Oswald's Ghost". American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Burkley, George Gregory (November 23, 1963). Certificate of Death. National Archives and Records Administration. front side, back side. NAVMED Form N – via The President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection.

- ^ Trek London (15 May 2023). "JF Kennedy's Death Certificate". TrekLondon UK. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Part IV". Appendix to Hearings before the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives. Vol. VII. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. March 1979. p. 190. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ a b "Commission Exhibit 387" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-06-25. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ^ a b c Appendix IX: Autopsy Report and Supplemental Report Archived 2007-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, Warren Commission Report, p. 541.

- ^ Appendix IX: Autopsy Report and Supplemental Report Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Warren Commission Report, p. 543.

- ^ Wagner, Robert A. (2016). The Assassination of JFK: Perspectives Half A Century Later. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 9781457543968. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Clark Panel On the Medical Evidence". Jfklancer.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ Allegations That President Kennedy Was Struck in the Head by a Bullet Fired From His Right Front Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 19: Allegations Concerning the Assassination of President Kennedy, Rockfeller Commission Report.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 382.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 383.

- ^ Trek London (12 February 2022). "JF Kennedy's Forensic Pathology Panel Reviews Autopsy Evidence". TrekLondon UK. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), pp. 382-383.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 384.

- ^ "Findings". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ "Findings". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 859.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 860.

- ^ Assassination Records Review Board (September 30, 1998). Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board, Chapter 1, p=7

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board, Chapter 1, p=1

- ^ Prepared Remarks by Douglas P. Horne, Former Chief Analyst for Military Records, Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB), Press Conference at the Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C., May 15, 2006.

- ^ a b c Lardner Jr., George (August 2, 1998). "Gaps in Kennedy Autopsy Files Detailed". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "Washingtonpost.com: JFK Assassination Report". www.washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ "Oliver Stone: JFK conspiracy deniers are in denial". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2013-11-22. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ "JFK Assassination: Kennedy's Head Wound". mcadams.posc.mu.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ "Clarifying the Federal Record on the Zapruder Film and the Medical and Ballistics Evidence". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ Saner, Emine. "The president's brain is missing and other mysteriously mislaid body parts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 385.

- ^ Lane (1966), p. 62.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1057.

- ^ a b Bugliosi (2007), p. 1058.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1059.

- ^ Bugliosi (2007), p. 1060.

Works cited

[edit]- Boyd, John W. (2015). Parkland. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467134002.

- Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 9780393045253.

- Lane, Mark (1966). Rush to Judgement. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 9781940522005.

- Lifton, David (1982). Best evidence: Disguise and Deception in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. Dell Publishing. ISBN 9780025718708.

- President John F Kennedy Assassination Report of the Warren Commission (Report). 2004. ISBN 0974776912.

- Sibert/O'Neill FBI autopsy report original.

- A second cached version at archive.today (archived 2012-12-15). This primary document preserves the notes of two FBI agents (Special Agents James W. Sibert and Francis X. O'Neill) who were present at the autopsy and took notes. It is helpful on times and personnel, but the agents were non-medically trained people who did not completely understand what they were seeing in the actual autopsy wounds. Moreover, the early report preserves genuine medical doctor confusion present actually during the autopsy, caused by apparent lack of an exit wound, which was cleared up later in the official report after new and more complete information became available. However, as a primary piece of observation by medical laymen, the report is useful.

- Official autopsy written report, taken from the Warren Commission report, CE (Commission Exhibit) 387.

- Joe Backes, The State of the Medical Evidence in the JFK Assassination; Doug Horne's presentation at JFK Lancer 1998 Conference.

- JFK Assassination Medical Evidence.

- Compilation of JFK Autopsy Photos (2010) Archived 2017-10-31 at the Wayback Machine