Barabási–Albert model

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

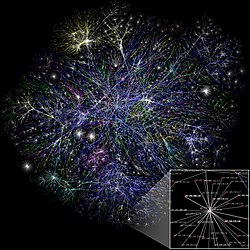

The Barabási–Albert (BA) model is an algorithm for generating random scale-free networks using a preferential attachment mechanism. Several natural and human-made systems, including the Internet, the world wide web, citation networks, and some social networks are thought to be approximately scale-free and certainly contain few nodes (called hubs) with unusually high degree as compared to the other nodes of the network. The BA model tries to explain the existence of such nodes in real networks. The algorithm is named for its inventors Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert and is a special case of a more general model called Price's model[1]

Concepts

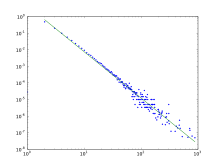

Many observed networks (at least approximately) fall into the class of scale-free networks, meaning that they have power-law (or scale-free) degree distributions, while random graph models such as the Erdős–Rényi (ER) model and the Watts–Strogatz (WS) model do not exhibit power laws. The Barabási–Albert model is one of several proposed models that generate scale-free networks. It incorporates two important general concepts: growth and preferential attachment. Both growth and preferential attachment exist widely in real networks.

Growth means that the number of nodes in the network increases over time.

Preferential attachment means that the more connected a node is, the more likely it is to receive new links. Nodes with higher degree have stronger ability to grab links added to the network. Intuitively, the preferential attachment can be understood if we think in terms of social networks connecting people. Here a link from A to B means that person A "knows" or "is acquainted with" person B. Heavily linked nodes represent well-known people with lots of relations. When a newcomer enters the community, s/he is more likely to become acquainted with one of those more visible people rather than with a relative unknown. The BA model was proposed by assuming that in the World Wide Web, new pages link preferentially to hubs, i.e. very well known sites such as Google, rather than to pages that hardly anyone knows. If someone selects a new page to link to by randomly choosing an existing link, the probability of selecting a particular page would be proportional to its degree. The BA model claims that this explains the preferential attachment probability rule. However, in spite of being quite a useful model, empirical evidence suggests that the mechanism in its simplest form does not apply to the World Wide Web as shown in "Technical Comment to 'Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks'". However, later Bianconi–Barabási model addresses this issue by introducing a fitness parameter. Preferential attachment is an example of a positive feedback cycle where initially random variations (one node initially having more links or having started accumulating links earlier than another) are automatically reinforced, thus greatly magnifying differences. This is also sometimes called the Matthew effect, "the rich get richer", and in chemistry autocatalysis.

Algorithm

The network begins with an initial connected network of nodes.

New nodes are added to the network one at a time. Each new node is connected to existing nodes with a probability that is proportional to the number of links that the existing nodes already have. Formally, the probability that the new node is connected to node is[2]

where is the degree of node and the sum is made over all pre-existing nodes (i.e. the denominator results in twice the current number of edges in the network). Heavily linked nodes ("hubs") tend to quickly accumulate even more links, while nodes with only a few links are unlikely to be chosen as the destination for a new link. The new nodes have a "preference" to attach themselves to the already heavily linked nodes.

Properties

The degree distribution resulting from the BA model is scale free, in particular, it is a power law of the form

Hirsch index distribution

The h-index or Hirsch index distribution was shown to also be scale free and was proposed as the lobby index, to be used as a centrality measure[4]

Furthermore, an analytic result for the density of nodes with h-index 1 can be obtained in the case where

Average path length

The average path length of the BA model increases approximately logarithmically with the size of the network. The actual form has a double logarithmic correction and goes as[5]

The BA model has a systematically shorter average path length than a random graph.

Node degree correlations

Correlations between the degrees of connected nodes develop spontaneously in the BA model because of the way the network evolves. The probability, , of finding a link that connects a node of degree to an ancestor node of degree in the BA model for the special case of is given by

This is certainly not the result expected if the distributions were uncorrelated, .[2]

For general , the fraction of links who connect a node of degree to a node of degree is[6]

Also, the nearest-neighbor degree distribution , that is, the degree distribution of the neighbors of a node with degree , is given by[6]

In other words, if we select a node with degree , and then select one of its neighbors randomly, the probability that this randomly selected neighbor will have degree is given by the expression above.

Clustering coefficient

While there is no analytical result for the clustering coefficient of the BA model, the empirically determined clustering coefficients are generally significantly higher for the BA model than for random networks. The clustering coefficient also scales with network size following approximately a power law

Edit: Analytical result for the clustering coefficient of the BA model was obtained by Klemm and Eguíluz[7] and proven by Bollobás.[8] A mean-field approach to study the clustering coefficient was applied by Fronczak, Fronczak and Holyst.[9]

This behavior is still distinct from the behavior of small-world networks where clustering is independent of system size. In the case of hierarchical networks, clustering as a function of node degree also follows a power-law,

This result was obtained analytically by Dorogovtsev, Goltsev and Mendes.[10]

The spectral density of BA model has a different shape from the semicircular spectral density of random graph. It has a triangle-like shape with the top lying well above the semicircle and edges decaying as a power law. [11]

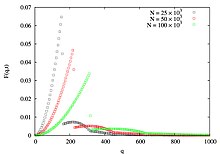

By definition, the BA model describes a time developing phenomenon and hence, besides its scale-free property, one could also look for its dynamic scaling property. In the BA network nodes can also be characterized by generalized degree , the product of the square root of the birth time of each node and their corresponding degree , instead of the degree alone since the time of birth matters in the BA network. We find that the generalized degree distribution has some non-trivial features and exhibits dynamic scaling

It implies that the distinct plots of vs would collapse into a universal curve if we plots vs .[12]

Limiting cases

Model A

Model A retains growth but does not include preferential attachment. The probability of a new node connecting to any pre-existing node is equal. The resulting degree distribution in this limit is geometric,[13] indicating that growth alone is not sufficient to produce a scale-free structure.

Model B

Model B retains preferential attachment but eliminates growth. The model begins with a fixed number of disconnected nodes and adds links, preferentially choosing high degree nodes as link destinations. Though the degree distribution early in the simulation looks scale-free, the distribution is not stable, and it eventually becomes nearly Gaussian as the network nears saturation. So preferential attachment alone is not sufficient to produce a scale-free structure.

The failure of models A and B to lead to a scale-free distribution indicates that growth and preferential attachment are needed simultaneously to reproduce the stationary power-law distribution observed in real networks.[2]

History

The first use of a preferential attachment mechanism to explain power-law distributions appears to have been by Yule in 1925.[14] The modern master equation method, which yields a more transparent derivation, was applied to the problem by Herbert A. Simon in 1955[15] in the course of studies of the sizes of cities and other phenomena. It was first applied to the growth of networks by Derek de Solla Price in 1976[16] who was interested in the networks of citation between scientific papers. The name "preferential attachment" and the present popularity of scale-free network models is due to the work of Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert, who rediscovered the process independently in 1999 and applied it to degree distributions on the web.[3]

See also

- Bianconi–Barabási model

- Chinese restaurant process

- Complex networks

- Erdős–Rényi (ER) model

- Price's model

- Scale-free network

- Small-world network

- Watts and Strogatz model

References

- ^ Albert, Réka; Barabási, Albert-László (2002). "Statistical mechanics of complex networks". Reviews of Modern Physics. 74 (1): 47–97. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47. ISSN 0034-6861.

- ^ a b c Albert, Réka; Barabási, Albert-László (2002). "Statistical mechanics of complex networks" (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 74: 47–97. arXiv:cond-mat/0106096. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47.

- ^ a b Barabási, Albert-László; Albert, Réka (October 1999). "Emergence of scaling in random networks" (PDF). Science. 286 (5439): 509–512. arXiv:cond-mat/9910332. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. PMID 10521342.

- ^ Korn, A.; Schubert, A.; Telcs, A. (2009). "Lobby index in networks". PhysicsA. 388: 2221–2226. arXiv:0809.0514. Bibcode:2009PhyA..388.2221K. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2009.02.013.

- ^ Cohen, Reuven; Havlin, Shlomo (2003). "Scale-Free Networks Are Ultrasmall". Physical Review Letters. 90 (5): 058701. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 12633404.

- ^ a b Fotouhi, Babak; Rabbat, Michael (2013). "Degree correlation in scale-free graphs". The European Physical Journal B. 86 (12): 510. arXiv:1308.5169. Bibcode:2013EPJB...86..510F. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2013-40920-6.

- ^ Klemm, K.; Eguíluz, V. C. (2002). "Growing scale-free networks with small-world behavior". Physical Review E. 65 (5). arXiv:cond-mat/0107607. Bibcode:2002PhRvE..65e7102K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.057102.

- ^ http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.176.6988

- ^ http://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0306255

- ^ Dorogovtsev, S.N.; Goltsev, A.V.; Mendes, J.F.F. (25 June 2002) [8 Dec 2001 (v1)]. "Pseudofractal scale-free web". Physical Review E. 65: 066122. arXiv:cond-mat/0112143. Bibcode:2002PhRvE..65f6122D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.066122.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Farkas, I.J.; Derényi, I.; Barabási, A.-L.; Vicsek, T. (20 July 2001) [19 February 2001]. "Spectra of "real-world" graphs: Beyond the semicircle law". Physical Review E. 64: 026704. arXiv:cond-mat/0102335. Bibcode:2001PhRvE..64b6704F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.64.026704.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ M. K. Hassan, M. Z. Hassan and N. I. Pavel, “Dynamic scaling, data-collapseand Self-similarity in Barabasi-Albert networks” J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 44 175101 (2011) http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/44/17/175101

- ^ Pekoz, Erol; Rollin, A.; Ross, N. (2012). "Total variation and local limit error bounds for geometric approximation". Bernoulli.

- ^ Yule, G. Udny; Yule, G. Udny (1925). "A Mathematical Theory of Evolution Based on the Conclusions of Dr. J. C. Willis, F.R.S". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 88 (3): 433–436. doi:10.2307/2341419. JSTOR 2341419.

- ^ Simon, Herbert A. (December 1955). "On a Class of Skew Distribution Functions". Biometrika. 42 (3–4): 425–440. doi:10.1093/biomet/42.3-4.425.

- ^ Price, D.J. de Solla (September 1976). "A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes". Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 27 (5): 292–306. doi:10.1002/asi.4630270505.

![{\displaystyle p(k,\ell )={\frac {m(m+1)}{k(k+1)\ell (\ell +1)}}\left[1-{\frac {{\binom {2m+2}{m+1}}{\binom {k+\ell -2m}{\ell -m}}}{\binom {k+\ell +2}{\ell +1}}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/61edb7b1e331bf03242025f61b5c09d41ad88089)

![{\displaystyle p(\ell \mid k)={\frac {m(k+2)}{k\ell (\ell +1)}}\left[1-{\frac {{\binom {2m+2}{m+1}}{\binom {k+\ell -2m}{\ell -m}}}{\binom {k+\ell +2}{\ell +1}}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8961572b65d51cf1ffcda98b749c93271a894aad)