Bariloche

San Carlos de Bariloche

Bariloche | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Coat of arms of San Carlos de Bariloche Coat of arms | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Department | Bariloche |

| Established | 1902 |

| Government | |

| • Intendant | María Eugenia Martini |

| Area | |

• City | 220.27 km2 (85.05 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 893 m (2,930 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

• City | 113,450 |

| • Density | 520/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 113,450 |

| • Metro | 130,000 |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| Climate | Csb |

| Website | Official website |

San Carlos de Bariloche, usually known as Bariloche, is a city in the province of Río Negro, Argentina, situated in the foothills of the Andes on the southern shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake. It is located within the Nahuel Huapi National Park. After development of extensive public works and Alpine-styled architecture, the city emerged in the 1930s and 1940s as a major tourism centre with ski, trekking and mountaineering facilities. In addition, it has numerous restaurants, cafés, and chocolate shops. The city has a permanent population of 108,205 according to the 2010 census.

History

The name Bariloche comes from the Mapudungun word Vuriloche meaning "people from behind the mountain" (vuri = behind, che = people). The Poya people used the Vuriloche pass to cross the Andes, keeping it secret from the Spanish priests for a long time.

Spanish discovery and missions

Nahuel Huapi lake was known to Spaniards since the times of the Conquest of Chile. In the summer of 1552–1553, the Governor of Chile Pedro de Valdivia sent Francisco de Villagra to explore the area east of the Andes at the latitudes of the city of Valdivia. Francisco de Villagra crossed the Andes trough Mamuil Malal Pass and headed south until reaching Limay River in the vicinity of Nahuel Huapi Lake.[1]

Another early Spaniard to visit the zone of Nahuel Huapi Lake was the Jesuit priest Diego de Rosales. He had been ordered to the area by the Governor of Chile Francisco Antonio de Acuña Cabrera y Bayona, who was concerned about the unrest of the native Puelche and Poya after the slave-hunting expeditions carried out by Luis Ponce de León in 1649, who captured Indians and sold them into slavery. Diego de Rosales started his journey at the ruins of Villarica in Chile, crossed the Andes through Mamuil Malal Pass, and traveled further south along the eastern Andean valleys, reaching Nahuel Huapi Lake in 1650.[2]

In 1670 Jesuit father Nicolás Mascardi, based in Chiloé Archipelago, entered the area through the Reloncaví Estuary and Todos los Santos Lake to found a mission at the Nahuel Huapi Lake, which lasted until 1673.[1] A new mission at the shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake was established in 1703, backed financially from Potosí, thanks to orders from the viceroy of Peru.[1] Historians disagree if the mission belonged to the jurisdiction of Valdivia or Chiloé.[1] According to historic documents, the Poya of Nahuelhuapi requested the mission to be reestablished, apparently to forge an alliance with the Spaniards against the Puelche.[1]

The mission was destroyed in 1717 by the Poya following their disagreement with the superior of the mission. He had refused to give them a cow.[1] Soon thereafter authorities learned that four or five people travelling to Concepción had been killed by the Poya. The colonists assembled a punitive expedition in Calbuco and Chiloé.[1] Composed of both Spaniards and indios reyunos, the expedition did not find any Poya.[1]

In 1766 the head of the Mission of Ralún tried to reestablish the mission at Nahuel Huapi, but the following year, the Crown suppressed the Society of Jesus, ordering them out of the colonies in the Americas.[1]

Modern settlement

The area had stronger connections to Chile than the distant city of Buenos Aires during most of the 19th century, but the explorations of Francisco Moreno and the Argentine campaigns of the Conquest of the Desert established the claims of the Argentine government. It thought the area was a natural expansion of the Viedma colony, and the Andes were the natural frontier to Chile. In the 1881 border treaty between Chile and Argentina, the Nahuel Huapi area was recognised as Argentine.

The modern settlement of Bariloche developed from a shop established by Carlos Wiederhold. The German immigrant had first settled in the area of Lake Llanquihue in Chile. Wiederhold crossed the Andes and established a little shop called La Alemana (The German). A small settlement developed around the shop, and its former site is the city center. By 1895 the settlement was primarily made up of German-speaking immigrants: Austrians, Germans, and Slovenians, as well as Italians from the city of Belluno, and Chileans. A local legend says that the name came from a letter erroneously addressed to Wiederhold as San Carlos instead of Don Carlos. Most of the commerce in Bariloche related to goods imported and exported at the seaport of Puerto Montt in Chile. In 1896 Perito Moreno wrote that it took three days to reach Puerto Montt from Bariloche, but traveling to Viedma on the Atlantic coast of Argentina took "one month or more".[citation needed]

In the 1930s the centre of the city was redesigned to have the appearance of a traditional European central alpine town (it was called "Little Switzerland.") Many buildings were made of wood and stone. In 1909 there were 1,250 inhabitants; a telegraph, post office, and a road connected the city with Neuquén. Commerce continued to depend on Chile until the arrival of the railroad in 1934, which connected the city with Argentine markets.

Architectural development and tourism

Between 1935 and 1940, the Argentine Directorate of National Parks carried out a number of urban public works, giving the city a distinctive architectural style. Among them, perhaps the best-known is the Civic Centre.

Bariloche grew from being a centre of cattle trade that relied on commerce with Chile, to becoming a tourism centre for the Argentine elite. It took on a cosmopolitan architectural and urban profile. Growth in the city's tourist trade began in the 1930s, when local hotel occupancy grew from 1550 tourists in 1934 to 4000 in 1940.[3] In 1934 Ezequiel Bustillo, then director of the National Parks Direction, contracted his brother Alejandro Bustillo to build several buildings in Iguazú and Nahuel Huapi National Park (Bariloche was the main settlement inside the park). In contrast to subtropical Iguazú National Park, planners and developers thought that Nahuel Huapi National Park, because of its temperate climate, could compete with the tourism of Europe. Together with Bariloche, it was established for priority projects by national tourism development planners.[3]

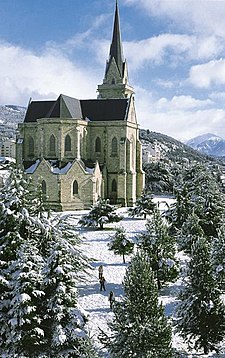

Alejandro Bustillo designed the Edificio Movilidad, Plaza Perito Moreno, the Neo-Gothic San Carlos de Bariloche Cathedral, and the Llao Llao Hotel. Architect Ernesto de Estrada designed the Civic Centre of Barloche, which opened in 1940. The Civic Centre's tuff stone, slate and fitzroya structures include the Domingo Sarmiento Library, the Francisco Moreno Museum of Patagonia, City Hall, the Post Office, the Police Station, and the Customs.

U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower visited Bariloche as a guest of President Arturo Frondizi in 1960. Classical violinist Alberto Lysy established the string quartet, Camerata Bariloche, here in 1967.

Huemul Project

| Patagonia |

|---|

|

| Regions |

|

Eastern Patagonia Western Patagonia Tierra del Fuego |

| Ecoregions |

|

Valdivian forests Magellanic forests Magellanic moorland Patagonian steppe |

| National parks |

|

Laguna San Rafael, Los Glaciares Nahuel Huapi, Torres del Paine Alberto de Agostini, Tierra del Fuego |

| Administrative division |

|

Chile Palena Province Aysén Region Magallanes Region Argentina Neuquén Province, Río Negro Province Chubut Province, Santa Cruz Province Tierra del Fuego Province |

During the 1950s, on the small island of Huemul, not far into lake Nahuel Huapi, former president Juan Domingo Perón tried to have the world's first fusion reactor built secretly. The project cost the equivalent of about $300 million modern US dollars, and it was never finished, due to the lack of the highly advanced technology that was needed. The Austrian Ronald Richter was in charge of the project. The facilities can still be visited, and are visible from certain locations on the coast.

Nazis in Bariloche

In 1995, Bariloche made headlines in the international press when it became known as a haven for Nazi war criminals, such as the former SS Hauptsturmführer Erich Priebke. Priebke had been the director of the German School of Bariloche for many years.

In his 2004 book Bariloche nazi-guía turística, Argentine author Abel Basti claims that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun lived in the surroundings of Bariloche for many years after World War II.[4] Basti said that the Argentine Nazis chose the estate of Inalco as Hitler's refuge.[4]

Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler, published by British authors Simon Dunstan and Gerrard Williams, proposed that Hitler and Eva Braun hid at Hacienda San Ramon, six miles east of Bariloche, until the early 1960s. Both these accounts are disputed by historians, who generally believe that Hitler and Braun died in the last days of World War II even though their bodies were never found.[5]

Tourism

Tourism, both domestic and international, is the main economic activity of Bariloche, all year around. While popular among Europeans, the city is also very popular among Brazilians. One of the most popular activities is skiing. Most tourists visit Bariloche in its winter (summer for North Americans and Europeans). Regular flights from Buenos Aires with LAN airlines and Aerolíneas Argentinas serve the city.

The main ski station is the one at Cerro Catedral. During the summer, beautiful beaches such as Playa Bonita and Villa Tacul welcome sun-bathers; brave lake swimmers venture into its cold waters (chilled by melting snow.) Lake Nahuel Huapi averages 14 °C in the summertime).

The fishing season is another great attraction. Bariloche is the biggest city of a huge Lakes District, and serves as a base for many excursions in the region. Trekking in the mountains, almost completely wild and uninhabited with the exception of a few high-mountain huts operated by Club Andino Bariloche, is also a popular activity. The city is noted for its chocolates and Swiss-style architecture.

Science

Besides tourism and related services, Bariloche is home of advanced scientific and technological activities. The Centro Atómico Bariloche is a research center of the National Atomic Energy Commission, where basic and applied research in many areas of the physical sciences is carried out. Inside it, the Instituto Balseiro, a higher education institution of the Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, with a small and carefully selected number of students, awards degrees in Physics, and in Nuclear and Mechanical Engineering, and Masters and Doctorate degrees in Physics and in Engineering. The city also hosts INVAP, a high-technology company that designs and builds nuclear reactors, state-of-the-art radars and space satellites, among other projects.

The private non-profit organization Bariloche Foundation continues the tradition of scientific research in the city. Started in 1963, it promotes postgraduate teaching and research. There are also several departments and laboratories at the National University of Comahue.

Climate and geography

Bariloche has a cool Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb) with dry, windy summers and rainy winters, which grades to an alpine subpolar oceanic climate at higher altitudes. Generally speaking, the summer season (mid-December to early March) is characterized by long stretches of windy, sunny weather, with pleasant afternoons of 18 to 26 °C (64 to 79 °F) and cold nights of 2 to 9 °C (36 to 48 °F). Autumn brings colder temperatures in March, then stormier weather in April and May. By mid-May the first snows fall, and winter lasts until early September, bringing stormy weather with mixed precipitation (snow, rain, sleet), occasional snowstorms and highs between 0 and 12 °C (32 and 54 °F), lows between −12 and 4 °C (10 and 39 °F). Spring is very windy and variable; temperatures may reach 25 °C (77 °F) in October and then plummet to −6 °C (21 °F) following a late-season snowfall. On average, there are a handful of snowy days between 5 and 15 centimetres (2 and 6 in) every year, and many more days with mixed precipitation. However, there have been extreme snow events in the past that have brought well over a foot of snow (30 cm) to the entire city, and well over a meter in some higher areas.

Within the city limits, several geographic features have an impact on the weather, creating several micro-climates. Generally, the city follows, for over 15 km from east to west, the shores of Nahuel Huapi lake, which is over 10 km wide in front of the city centre and extends over more than 70 km to the northwest, toward Villa La Angostura. West of the city, the fjord known as Brazo Blest extends for another 50 km, and these two features allow strong westerly and northwesterly winds to reach the city. Most central areas and almost all tourist areas are located along the shoreline; they are thus "sandwiched" between higher elevations on the south and the extensive lake at 765 meters above sea level on the north. This position, on a north-facing slope next to open water, creates a moderate micro-climate: during the summer, daytime temperatures very rarely reach over 30 °C, staying most often in the 18 °C to 25 °C range, with nights usually between 2 and 9 °C (36 and 48 °F). During the winter, most days reach between 3 and 9 °C (37 and 48 °F), whilst nights are often between −5 and 4 °C (23 and 39 °F), depending mostly on cloud cover. Snowfall is usually light, and although snow depth can often reach 0.1 metres (4 in) after a snowstorm, it will usually not last more than two or three days. Extreme low temperatures rarely fall below −10 °C (14 °F), although −15 °C (5 °F) may be reached on occasion. The main feature of this area is the strong, westerly winds that sometimes reach over 100 km/h, especially between September and December. Precipitation ranges from over 1,800 millimetres (70 in) at the western end of the city (Llao Llao) to only 600 millimetres (24 in) at the eastern end (Airport).

Right behind the city centre, the area known as "El Alto" forms a plateau at about 900 m of altitude. Being far away from the lake and at a higher altitude, the weather tends to be more extreme, especially in the winter: it is not uncommon to see sleet storms hit the downtown area while El Alto is covered in snow. It is also not unusual to have more extended periods of snow cover (up to one or two weeks at a time), with depths sometimes exceeding 0.2 metres (8 in), and temperatures of −10 °C (14 °F) are frequent. On occasion, temperatures below −18 °C (0 °F) will also be recorded.

The slopes of Cerro Otto (1405 meters above sea level), right west of the city centre, often have deep snow cover: cross-country skiing and dog sledding can be practiced for a few months every year. The neighbourhood of Villa Catedral, at about 990 meters above sea level, sees colder temperatures and increased snowfall: on the coldest winters, this hub, which serves as the base of a ski resort, can be snow-covered through the winter, sometimes with over 50 cm snow (in 2007, accumulations reached 100 cm). However, on most winters, this condition is only met above 1200 meters, where most of the slopes of the resort are located.

Higher elevations see much colder conditions; the top of Cerro Catedral, 30 km from the city centre, sees snow cover from late April to at least December, with a maximum in early September that usually reaches well over 150 cm (in 2007, over 400 cm were recorded). The tree line is located between 1,600 m (southerly slope) and 1,800 m (northerly slope). Snowstorms occur in the summer as well.

Water temperatures at the Nahuel Huapi lake vary from a high of 14 °C in late summer and a low of 7 °C in early spring. Alpine streams and ponds often have much lower temperatures, and can be frozen for months.

| Climate data for San Carlos de Bariloche (downtown) 1901–1950[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.3 (95.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.5 (92.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.2 (1.23) |

29.3 (1.15) |

61.7 (2.43) |

82.2 (3.24) |

173.4 (6.83) |

200.8 (7.91) |

167.8 (6.61) |

129.0 (5.08) |

83.1 (3.27) |

43.0 (1.69) |

51.9 (2.04) |

43.1 (1.70) |

1,096.5 (43.17) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62 | 64 | 67 | 73 | 80 | 82 | 81 | 78 | 72 | 68 | 67 | 65 | 72 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Secretaria de Mineria (extremes 1901–1950)[7] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Carlos de Bariloche Airport (1951–1990, extremes 1951–present)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.4 (93.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.7 (36.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.7 (21.7) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24.3 (0.96) |

19.7 (0.78) |

28.6 (1.13) |

52.8 (2.08) |

130.5 (5.14) |

126.9 (5.00) |

140.2 (5.52) |

115.3 (4.54) |

56.1 (2.21) |

34.7 (1.37) |

23.1 (0.91) |

30.4 (1.20) |

782.6 (30.81) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 24.3 (0.96) |

19.2 (0.76) |

28.6 (1.13) |

49.4 (1.94) |

123.5 (4.86) |

94.5 (3.72) |

98.5 (3.88) |

92.4 (3.64) |

49.9 (1.96) |

28.9 (1.14) |

22.9 (0.90) |

30.4 (1.20) |

662.5 (26.08) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.4 (1.3) |

7.0 (2.8) |

32.4 (12.8) |

41.7 (16.4) |

22.9 (9.0) |

6.2 (2.4) |

5.8 (2.3) |

0.2 (0.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

120.1 (47.3) |

| Average rainy days | 5.0 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 107.0 |

| Average snowy days | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 21.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 62 | 67 | 74 | 81 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 75 | 68 | 63 | 61 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 347.2 | 277.2 | 251.1 | 186.0 | 136.4 | 111.0 | 117.8 | 155.0 | 192.0 | 251.1 | 309.0 | 334.8 | 2,668.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 75 | 72 | 65 | 56 | 45 | 39 | 40 | 47 | 54 | 61 | 71 | 72 | 58 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (normals and extremes 1951–1990)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun and relative humidity 1961–1990),[8] Oficina de Riesgo Agropecuario (extremes 1991–present)[9] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

The city is served by San Carlos de Bariloche International Airport (IATA BRC/ICAO SAZS) equipped to receive any kind of aircraft. Several of Argentina's most important airlines maintain regular flights to Bariloche, as well as some international lines from neighbouring countries, especially during the ski season. The city is linked by train with the city of Viedma through the Tren Patagonico that crosses Argentina from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean.

San Carlos de Bariloche lies close to the Chilean border and is connected to Chile by the Cardenal Antonio Samoré Pass crossing the Andes Mountains.

The city has a terminal railway station that links it to Viedma.

Military

Bariloche is home of the army's "12° Regimiento de Infantería de Montaña" (12th Mountain Infantry Regiment), where military personnel are instructed in mountainous conditions, including combat, survival or even skiing. It is usual for the Regiment to receive infantry personnel from other parts of the country and train them. Furthermore, the Escuela Militar de Montaña, the mountain warfare school of the Argentine Army is located in Bariloche.[10]

Neighborhoods

The most important neighborhoods are Belgrano, Belgrano Sudeste, Jardín Botánico, Melipal, Centro and Playa Bonita. These are the most popular parts of the city.

Sports

The Andean Club Bariloche (Template:Lang-es) was co-organiser of the 1st and the 3rd South American Ski Mountaineering Championships.

Gallery

-

A typical log cabin in the outskirts of Bariloche.

-

Club Andino Bariloche

-

Cerro Catedral ski resort in July

-

Catedral Village

-

Puerto Pañuelo, at the nearby town of Llao Llao functions as Bariloche's port for boat tours.

-

Civic Centre and port on Lake Nahuel Huapi

-

View of the lake from Llao Llao Hotel

-

City view

-

On paso Int. Cardenal Samore

-

View of the Cathedral in San Carlos de Bariloche

Sister cities

| Country | City |

|---|---|

| Aspen | |

| La Massana | |

| Puerto Varas | |

| St. Moritz | |

| Sestriere | |

| Osorno | |

| Puerto Montt | |

| Zakopane |

See also

- Club Andino Bariloche

- Ferrocarril General Roca

- Huemul Project

- Nahuel Huapi National Park

- Servicios Ferroviarios Patagónico

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Urbina, Ximena (2008). "The frustrated strategic mission of Nahuelhuapi, a point in Patagonia's inmensity". Magallania. 36 (1): 5–30.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hanisch, Walter. 1974. Historia de la Compañía de Jesús en Chile, p. 33

- ^ a b Tourism Policy in 20th-century Argentina

- ^ a b http://www.absurddiari.com/s/llegir.php?llegir=llegir&ref=3656

- ^ Dewsbury, Rick; Hall, Allan; Harding, Eleanor (18 October 2011). "New book claims Hitler and Eva Braun fled Berlin and died (divorced) of old age in Argentina". London: The Daily Mail (UK). Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ a b Bustos, José; Rocchi, Victor. "Caracterizacíon Termopluviométrica de Algunas Estaciones Meteorológicas de Rio Negro Y Neuquén" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Provincia de Rio Negro − Clima Y Meteorologia: Datos Meteorologicos Y Pluviometicos" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ "Bariloche Aero Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Bariloche, Rio Negro". Estadísticas meteorológicas decadiales (in Spanish). Oficina de Riesgo Agropecuario. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ http://www.ejercito.mil.ar/sitio/_noticias/noticia_full.asp?Id=814 Template:Es icon, Argentine Army.

Notes

- ^ In the Secretaria de Mineria and INTA link, the data from 1901-1950 corresponds to the data recorded in the downtown station (Bariloche Ciudad) while the data from 1951-1990 corresponds to the data recorded from the airport

- ^ The record highs and lows are based on the INTA link for the period 1951–1990 while records beyond 1990 come from the Oficina de Riesgo Agropecuario link since it only covers from 1970–present. As a result, the most extreme values from either source are used.