Battle of Slim Buttes

| Battle of Slim Buttes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Sioux War of 1876 | |||||||

General Crook's field headquarters during the “Horsemeat March”, 1876 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Lakota |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

American Horse † Crazy Horse |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~600–800 | ~1200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10 killed unknown wounded 23 captured |

3 killed 27 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Slim Buttes was fought on September 9 and 10, 1876, in the Great Sioux Reservation in the Dakota Territory, between the United States Army and the Sioux.

The Battle of Slim Buttes was the first U.S. Army victory of the Great Sioux War of 1876 after General George Custer’s defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn on June 25 and 26, 1876. Brigadier General George Crook, one of the U.S. Army’s ablest Indian fighters, led the “Horsemeat March”, one of the most grueling military expeditions in American history, destroying Oglala Chief American Horse’s village at Slim Buttes and repelling a counter-attack by Crazy Horse. The American public was fixed on news of the defeat of Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn and war correspondents with national newspapers fought alongside General Crook and reported the events. The Battle of Slim Buttes signaled a series of punitive blows that ultimately broke Sioux armed resistance to reservation captivity and forced their loss of the Black Hills “Paha Sapa“.[1]

Prelude to war

Black Hills Gold Rush

In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a military expedition of one thousand men from Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck, to investigate reports of gold and to determine a suitable location for a military fort in the Black Hills of the Great Sioux Reservation. Before Custer's column had returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln, news of the discovery of gold in the Black Hills was telegraphed as an international news event.[2] War correspondent John A. Finerty reported: “A wall of fire, not to mention a wall of Indians, could not stop the encroachment of that terrible white race before which all other races of white kind have gone down. At the news of gold the grizzled 49‘ers shook the dust of California from their feet and started for the far distant ‘Hills.’ The Australian miner left his pack and started by saddle and ship for the same goal; the diamond hunter of the Cape, the veteran prospector of Colorado an Montana, the reduced gentleman of Europe, the worried and worn clerks of London, Liverpool, New York, or Chicago, the study Scotchman and the light-hearted Irishman, who drinks the spirit of adventure with his mother’s milk, the miners of Wales and Cornwall and the gamblers of Monte Carlo came trooping in masses to the new Eldorado.”[3]

Safety of the settlers

Custer's announcement of gold in the Black Hills triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush. With an influx of thousands of immigrants, mining towns and settlements began to spring-up throughout the Black Hills and tensions increased between the Sioux and whites. The U.S. government was alarmed at reports of frequent Sioux attacks against miners and settlers.[4] In 1876, Custer City miners organized a 125-man militia known as the Black Hills Rangers to protect miners and settlements, and escort immigrants through dangerous canyons where angry Sioux often waited in ambush. Captain Jack Crawford was appointed as chief of scouts of a special unit of about twelve experienced fighting men to look for Indian signs.[5] War correspondent Robert Strahorn reported the deteriorating situation between settlers and Indians: “Not one of the thousands restless spirits who had gathered in the Black Hills but had tasted or severely felt the fiendish hand of the red man bound for revenge for the occupancy of their country. Not less than 400 whites had been murdered since the previous spring, and no man was safe in venturing beyond the confines of the towns, which had been kept in a state of terror for many months of fear of a wholesale descent of such a force of Indians as we had just defeated, which would wipe out every soul and every vestige of their handiwork. When, as rarely happened, an Indian was killed, the settlement went wild with delight and his skull and scalp were paraded and sold to the highest bidder in the streets of Deadwood.”[6]

Manifest Destiny

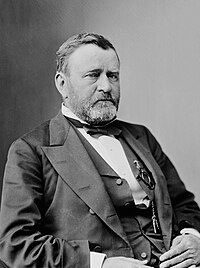

Initially, the U.S. Army made bona fide efforts to enforce The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 and evicted encroaching miners. “General Crook was using such of his forces as was possible to hold back the tide of gold seekers persisting in invading the Black Hills and Big Horn regions from the south, while General Terry at Fort Lincoln near Bismarck, was ineffectively endeavoring to restrain a like lawless flood from that direction.”[7] But after the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, U.S. Government policy and the role of the Army changed. “The presence of gold in the Black Hills left the government powerless, and soon unwilling, to turn aside a waive of prospectors that quickly followed.”[8] Immigration was skillfully promoted by the Northern Pacific Railroad in the U.S. and Europe to increase passenger revenues, and almost overnight, the Black Hills of the Great Sioux Reservation became a bee-hive of immigrants, mines and settlements. In May 1875, Lakota delegations headed by Red Cloud and Spotted Tail traveled to Washington, D.C. in an attempt to persuade President Ulysses S. Grant to halt the flow of miners into the Great Sioux Reservation. “Grant told the Sioux bluntly that they were being unreasonable in preventing white men from digging for gold. The government could not keep the gold hunters out. But if the Indians persisted in trying to stop them, there was certain to be bloodshed, and once blood was spilled, the government would be forced by the anger of the white people across the nation to remove the Sioux from the Black Hills. The Sioux were still not persuaded.”[9] Despite U.S. government pressure, Lakota leaders refused agree to amend the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 or discuss selling the Black Hills.[10] At this time, Americans in the 19th century believed in the “Manifest Destiny” of the United States to expand across the continent to the Pacific, and there was increasing political pressure on President Grant to annex the Black Hills from the Sioux.[11]

Grant's ultimatum

In 1875, Sitting Bull created the Sun Dance alliance between the Lakota and the Cheyenne. On November 9, 1875, Indian Inspector E.C. Watkins complained of the attitude of certain wild and hostile Indians, “composed of a small band of 30 or 40 lodges under Sitting Bull, who has been an out-and-out anti-agency Indian, and the bands of other chiefs and headmen under Crazy Horse, an Ogallalla Sioux, belonging formerly to the Red Cloud agency, numbering about one hundred and twenty lodges.”[12] Many "Agency Indians" joined Sitting Bull’s camp for a seasonal hunt and a stand against reservation life.[13] Chief Sitting Bull took an active role in encouraging the "unity camp" and sent scouts to reservations to recruit warriors. In November 3, 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant met with Secretary of the Interior Zachariah Chandler, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Edward P. Smith, Secretary of War William W. Belnap, General Philip Sheridan and General George Crook on the issue of the Black Hills. President Grant ordered the U.S. Army to maintain but not enforce the prohibition on miners entering the Black Hills, and ordered the “hunting bands” to yield the unceded lands and accept reservation life by January 31, 1876, or face military action.[14] Concerned about launching a war against the Lakota without provocation, the government instructed Indian agents in the region to notify the various non-treaty bands to return to the reservation by January 31, 1876, or face potential military action. The US agent at Standing Rock Agency expressed concern that this was insufficient time for the Lakota to respond, as deep winter restricted travel. His request to extend the deadline was denied. General Sheridan considered the notification exercise a waste of time. "The matter of notifying the Indians to come in is perhaps well to put on paper," he commented, "but it will in all probability be regarded as a good joke by the Indians." Sheridan endorsement, February 4, 1876, National Archives. On his recommendation, approved by the Indian Commissioner and the Secretary of the Interior, it was ordered ‘that these Indians be informed that they must remove to a reservation before January 31, 1876, and that in event of their refusal to come in by the time specified, they would be turned over to the War Department for punishment.[15] The U.S. government knew the Indians could not or would not comply.[16] “By the time this order got out to the Indian country it seemed to mean something else, for many other bands of Sioux were off reservations. It was not practical for them to pick up and move in midwinter. But apparently they though the order applied to them, whereupon their trend was toward Sitting Bull, not toward the reservations.[17] “The deadline was completely unrealistic even if the bands had wanted to acquiesce. It barely allowed enough time to notify the widely scattered groups, let alone permit them to travel through the difficult winter weather to the reservations.”[18] On February 8, 1876, after the expiration of the January 31, 1876, ultimatum the U.S. government declared war on the Sioux. Secretary of the Interior Department turned the matter of the Black Hills over to the War Department to commence punitive warfare, force the submission of hostile Lakota and Cheyenne, pacify the Northern Plains and take control of the Black Hills in the Great Sioux Reservation.[19]

The Great Sioux War

Great Sioux War begins

On February 8, 1876, The Great Sioux War began when President Ulysses S. Grant ordered the U.S. Army to secure the Black Hills and force the submission of “hostile” Lakota.[20] Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, commanding the Department of Missouri, thereupon ordered Generals Alfred Terry and George Crook to commence punitive warfare, force the submission of “hostile” Lakota and Cheyenne and take control of the Back Hills in the Great Sioux Reservation.[21] The Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition was the largest field command to face Indian warriors in combat during the late nineteenth century.[22]

Battle plan

General Sheridan, assuming non-compliance with the ultimatum, planned his military action carefully. A multi-pronged approach was envisioned. General Crook would move north from Fort Fetterman in Wyoming. General Alfred Terry would split his forces with Colonel John Gibbon moving east from Fort Ellis in Montana, and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer descending from Fort Abraham Lincoln and turning westward. The three prongs would encircle the Lakotas and their Cheyenne allies and destroy them, eliminating the primary opposition on the Plains, including the two men considered the greatest threats to U.S. expansion: Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. In reality, the harsh weather that would have prevented the Indian band from complying with the ultimatum also prevented Sheridan from implementing his plans during the heart of winter, when he hoped to find the bands in their winter camps and more vulnerable to attack. Crook was concerned that as spring progressed and the weather improved, hundreds more Indians might leave the reservations to join the war bands, and he wanted to locate and destroy the camps and villages as soon as possible. The camps of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were thought to be located in the region of the headwaters of the Powder, Tongue, and Rosebud rivers.[23] Strahorn described the rigors of the Great Sioux War: “In a dozen engagements in which I participated there were only a couple of weeks of real fighting, while the pursuit of the Indians to gain that result involved over a year of continuous and most arduous hunting for them, the various marches totaling about 4000 miles. Much of this was accomplished in blizzards, in far below-zero temperatures, without tents or adequate bedding, alternating with blistering and famishing lack of water. Most of it was fatiguing and monotonous in the extreme, and a lot of it on half and quarter rations, some of it only horse meat, supplied by our worn-out and dying horses.”[24]

Ft. Laramie 1876

Strahorn’s first introduction to military life was Ft. Laramie at the onset of the Great Sioux War in early 1876. “Fort Laramie’s officers were a jolly crew and its family and community life most appealing. On our first night there the small garrison of two hundred souls trotted out a theatrical entertainment, purely military, that would have done credit to any city. The leading man and lady gave an especially fine performance, and the support was excellent. Entertainment by the officer’s families to whom we were always apportioned at the pots, was so charming, that being my first experience of the kind, I was at a loss to respond adequately.“[25] “The night before our departure I had begged to be allowed to do my writing, at which I continued until an early morning hour. While still deeply absorbed in this work, a file of hilarious officers celebrating the morrow’s parting entered singing, and proceeded to march around my table with jolly antics and interference with my work, such as scattering my manuscript to the four corners of the room. This march continued until, to satisfy them, I joined the procession and they wound up their marching with “He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Then something awful occurred! During the very cordial “good night” exchange I was introduced to an officer I had not previously met. I had never been among army men and was unaccustomed to the use of their likes. I committed the very grave offense of addressing him as “Mr.” He fairly shrieked at me. “Major Johnson, sir! Major Johnson, G-d d__m you!” I replied, “You may have somehow become a major, but you still have some marching to do to become a gentleman!” He jumped for the assault, but was pinioned by the other officers, who finally cooled him down, and all left as gracefully as possible under the strained conditions, but not without freely criticizing him and assuring me that I was entirely justified in my rejoinder. Right here I want to say that I never, except in this case and one other when it was necessary for me to appear at a court-martial against an officer whom I had truthfully accused of cowardice, have I had any other than the most cordial, and often affectionate, treatment by rank and file of the military.”[26]

Captain Jack joins General Crook

Captain Jack’s daring ride of 350 miles in six days to carry dispatches to Fort Laramie for the New York Herald to tell the news of the great victory at the Battle of Slim Buttes made him a national celebrity. Captain Jack Crawford traveled for over two weeks, trying to catch up with General Crook’s command. On July 24, 1876, Jack boarded a train for Cheyenne en route to Ft. Laramie. When Crawford reached Cheyenne, he discovered that the Fifth Cavalry had already left for Fort Laramie and was en route north to Fort Fetterman. On July 29, Jack arrived at Fort Fetterman and credited with carrying dispatches on a highly perilous route of four hundred miles. On August 2, Jack left Fort Fetterman and finally reached Crook’s command camped on Rosebud Creek in Montana on August 8, 1876.[27] “After a brief nap, Crawford located his friend Buffalo Bill, handed him some letters, and distributed other communications to officers and newspaper correspondents accompanying the expedition. He then turned over to Cody a present from a Mr. Jones, proprietor of the Jones House in Cheyenne. The gift was a bottle of sour-mash whiskey, which Jack had carried unharmed on his perilous journey to the Rosebud. In wiring of this incident in his autobiography, published in 1879, Cody whimsically remarked: “Jack Crawford is the only man I have ever known that could have brought that bottle of whiskey through without “accident befalling it, for he is one of the very few teetotal scouts I ever met. Indeed, Crawford made a good impression upon both officers and enlisted men, who considered his ride from Fetterman a “plucky undertaking.”[28] “Our campfires were lively after Captain Jack joined us,” recalled an officer. “He sang his songs, told his stories, recited his poems and kept his tireless jaw constantly wagging for our edification.”[29]

Powder River fight

On March 16, 1876, Grouard reported that he had discovered a small band of Indians who had come from the main Crazy Horse camp. “A council of war was held and it was concluded our force should be divided into two squads, General Crook to follow the easterly fresh trail, and Colonel Reynolds to lead the other, consisting of about three hundred men, for the attack upon the camp.”[30] On March 17, 1876, the first major battle began when Colonel Reynolds discovered a Cheyenne village on the Powder River in southeast Montana Territory and attacked village by surprise. Strahorn took part in Colonel Joseph J. Reynolds' charge on the Powder River village in March 17, 1876, screaming so loudly and so long in the wintery air that he damaged his vocal chords permanently.[31] Reynolds scattered the Indians, burned tipis, destroyed food supplies and captured a large pony herd. However, after a five-hour battle, Reynolds lost the initiative when Indians regrouped and retrieved their ponies.[32] The Powder River fight was a reversal for Crook and he was furious. Reynolds had struck a peaceful camp of Northern Cheyenne who thereafter became belligerents in the Sioux War. Reynolds also burned valuable provisions which Crook had intended to use and left several troopers behind in a retreat. As a result, Crook was forced the withdraw his command from the region until late spring, and Reynolds was court martialed.[33]

Battle of the Rosebud

In late spring, after the Powder River Fight, Crook again proceeded north along Montana’s Rosebud trying to locate and engage the Indians. On June 17, 1876, General Crook’s column was attacked by Crazy Horse and about 750 Lakota and Cheyenne warriors in a six-hour battle on Rosebud Creek. The Lakota and Cheyenne forces withdrew, and Crook claimed victory as possessor of the battlefield. However, the battle halted Crook’s northward advance in the three-pronged attack and he was unable to join with Gen. Terry and Custer’s 7th Cavalry.[34] In need of supplies and reinforcements, Crook withdrew from the Rosebud to his camp on Goose Creek and regrouped until August 1, 1876. “Crook struck the fringes of the gathering concentration one week before Custer did.”[17] “His battle of the Rosebud on June 17, 1876, beat off the Indian attack, driving the Sioux northward as contemplated in Sheridan’s plan. From that point of view it was regarded as a victory. Crook had seriously wounded men to care for, His supplies of food and ammunition were used up. Therefore, he fell back to Goose Creek to reorganize.”[17]

The Little Big Horn

Custer’s 7th Cavalry regiment was a major component of General Terry’s column. Custer ascended the Little Big Horn in search of an Indian village and attacked on June 26, 1876.[35] “No one had any idea that all of the Indians would be found in one spot on the Little Big Horn.”[17] “By June 23, 1876, Sitting Bull’s Camp, following the Rosebud Battle, more than doubled in size to over 1000 lodges and 7000 inhabitants. There were an estimated 1500 to 2000 warriors from Northern Cheyenne and five major Sioux tribes. The Indians had no intention of fleeing. They were determined to stand and fight.”[36] On June 25 and 26, 1876, George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry (with 468 fatalities and 55 wounded) were defeated at the Battle of the Little Big Horn by Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. News of the defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25 and 26, 1876, arrived in the East as the U.S. was observing its centennial.[37] The public and the government were in dismay. Western news editors called for a speedy “prosecution of the war in a manner so vigorous that the fiends of the plains will be glad to surrender their arms.” The hostiles should be “exterminated root and branch, old and young, male and female.” Eastern editors also expressed alarm but mirrored geographical detachment and humanitarian tendencies in their more subdued urgency. We must beat the Sioux,” printed a New York Times editorial, “but we need not exterminate them.”[38]

The Battle of Slim Buttes

Prelude to the Battle of Slim Buttes

After defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Gen. Sheridan took immediate action and placed the Sioux agencies under military law and made the civil administrators subordinate, guns and horses of Indians at the agencies were seized, Indian Scouts were temporarily disbanded and additional troops were called to replace Custer’s dead. In early August, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to add an additional 2500 men to the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition to meet the emergency.[39] Beginning in July, the 7th Cavalry was reinforced and reorganized.[40] On August 1, 1876, Crook moved his command back into the field having received reinforcements during July.[41] On August 8, 1876, Captain Jack Crawford arrived to join Crook, and Terry’s command was further reinforced with the 5th Infantry, and moved up Rosebud Creek in pursuit of the Lakota. Terry met with Crook's command, similarly reinforced, and the combined force, almost 4000 strong, followed the Lakota trail northeast toward the Little Missouri River. Persistent rain and lack of supplies forced the column to dissolve and return to its varying starting points, and the 7th Cavalry returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln to reconstitute. However, the combined force of 4000 men was too big and unwieldy to take an offensive and the wagon train of supplies was left behind to unencumber the pursuit. On August 10, Crook and Terry’s columns met.[42] Crook and Terry’s combined force then moved east toward the Black Hills. On August 20, 1876, the Shoshone, Ute and Crow allies left the command, voting the campaign a failure.[43] On August 26, Crook and Terry split. The bad weather, extreme muddy conditions on the trail overtaxed men and animals, and Terry returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota, to disarm Indians at the Sioux agencies.

Crook’s Horsemeat March

Crook’s "Horsemeat March” marked the beginning of one of the most grueling marches in American military history. Crook’s command consisted of about 2200 men: 1500 cavalry, 450 infantry, 240 Indian scouts, and a contingent of civilian employees, including 44 white scouts and packers. Crook’s civilian scouts included Frank Grouard, Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier, Baptiste “Little Bat” Garnier, Captain Jack Crawford and Charles “Buffalo Chips” White.[44] “Although Captain Jack’s “yarns and rhymes” would help to relieve the monotony of camp life, Buffalo Bill grew bored by the inactivity and left the expedition to continue his theatrical career in the East. According to one newspaper account, it was on Cody’s recommendation that Col. Wesley Merritt subsequently appointed Crawford to succeed Cody as chief of scouts of the 5th Cavalry Regiment.”[45] News of the defeat of General Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25 and 26, 1876, arrived in the East as the U.S. was observing its centennial.[46] The American public was in dismay, called to punish the Sioux, and awaited the government’s response. War correspondents with national newspapers fought alongside General Crook and reported the campaign by telegraph. Correspondents embedded with Crook were Robert E. Strahorn for the New York Times, Chicago Tribune and the Rocky Mountain News; John F. Finerty for the Chicago Times; Reuben Briggs Davenport for New York Herald and Joe Wasson for the New York Tribune and Alta California (San Francisco).[47] On August 26, 1876, with his men rationed for fifteen days, General Crook departed from the Powder River and headed east toward the Little Missouri, pursuing the Indians. Crook feared that the Indians would scatter to seek game rather than meet the soldiers in combat after the fight with Custer. All other commanders had withdrawn from pursuit, but Crook resolved to teach the Indians a lesson. He meant to show that neither distance, bad weather, the loss of horses, nor the absence of rations could deter the U.S. Army from following up its enemies to the bitter end.[48] Strahorn reported that “all the infantrymen who could ride and who so wished were mounted on mules from the pack train. No circus ever furnished a better show in its mule-riding department than we enjoyed when those two hundred infantrymen essayed their first mount. Many of them had never been astride a horse and many of the mules had never been ridden. Tom Moore, Chief of Pack Trains, and his battalion of assistance, had the time of their lives trying to mount and hold the men in their saddles for the first hours of the performance. Not a few of the soldiers, after being pitched into the sagebrush and cactus a few times, contended they would sooner walk. However, galled but gallant, nearly two hundred stuck to the mules.”[49]

An accident befell Strahorn during the advance. During a rainstorm, he became entangled in his gear and his horse bucked dragging him face first through prickly pear and cactus. With the help of surgeons, it took weeks to painfully extract the barbs. He remarked, “I was in good mood for an Indian fight or any other distracting adventure.”[50]

“The days soon arrived when, on forced marches after the enemy, all discharges of firearms except at the enemy were strictly prohibited under severe penalty. Being out on the right flank one day, just out of sight of the troops, I came upon a beautiful covey of grouse. They were so tame I could almost knock them over with rocks, but while the contact thus established made me increasingly anxious for grouse for dinner that night, I could not hit them. So finally, in spite of those orders and with growing appetite, I shot two of them and quickly secreted the evidence of my disobedience by rolling them up in the rain coat I carried on my saddle. The right wing of the command was wildly excited by the shots. The skirmishers thrown out on that side soon discovered my lonely presence and hustled me to Colonel Chambers with the news that no Indians were visible. He very sternly asked. ‘Mr. Strahorn, did you do that firing?” Upon my answering, “Yes sir,” he still more gruffly asked, “At Indians, or what?” “Not at Indians, Colonel, but at grouse,” I answered. “I was so hungry for grouse that I just couldn’t help it, so I’m ready to pay the penalty. What is it?’ Be it remembered that I was in the Colonel’s mess, and he replied quietly on the side, ‘Well, it will make a damn sight of difference whether you got a grouse.’”[51]

Crook soon began running short of food and supplies and ordered his men to go on half rations. Many of the men were forced to subsist on horsemeat and the expedition was thereafter known as “General Crook’s Horsemeat March.”[52] Without grain and adequate forage, horses and mules had weakened and many collapsed in the steady rain and mud. Crook had already given orders to shoot abandoned animals for food, and for several days his saddened, ragtag army would exist on a diet of mule and horsemeat. “The horses commenced to play out. As fast as the poor brutes fell the quartermaster had them killed and issued as rations, so the soldiers had nothing but played-out horses to eat from there on into the Hills. It looked funny to see a soldier ride his horse until it dropped exhausted, and then get off and shoot it and cut up its carcass up and issue meat to the soldiers of different companies. Gen. Crook would not take any advantage of his command. If they starved, he starved with them.”[53] But the soldiers were nearing total exhaustion; wet, hungry, disheartened by constant hardships. One officer wrote that he saw: ”men who were very plucky sit down and cry like children because they could not hold out.” Years later, Colonel Andrew S. Burt would reminisce with Crawford about the hardships they had shared on this grueling march: hunger, marching in the rain, sleeping on wet, muddy ground, eating horse meat. He vividly recalled Jack squatting on the ground before a campfire, “gnawing at a horse’s rib flesh from the coals and glad to get the rib.” [54]

Frank Grouard, chief of scouts

Grouard’s early days

Frank Grouard was General Crook’s chief scout and interpreter during the Great Sioux War. Strahorn became friends with Grouard and journaled his story. Grouard was born in the Society Islands in the south Pacific Ocean, the second of three sons born to Benjamin Franklin Grouard, an American Mormon missionary of French Huguenot heritage, and a Polynesian woman. Grouard moved to Utah with his parents and two brothers in 1852, later moving to San Bernardino, California. After a year in California, Grouard’s mother returned to the South Pacific with two of the children, leaving Frank with his father. In 1855, Frank was adopted into the family of Addison and Louisa Pratt, fellow Mormon missionaries of his father. Grouard moved with the Pratt family to Beaver, Utah, from where he ran away at age 15, moving to Helena, Montana, and becoming an express rider and stage driver between frontier posts. In about 1869, while working as a mail carrier, Grouard was captured in a Crazy Horse foray, and taken to a distant camp in northern Wyoming, where he was closely guarded for several years to prevent escape. On account of his dark skin and black hair he was believed by his captors to be an Indian. Meanwhile, being fond of adventure, he gradually fell into their ways. He was not only adopted into their tribe, but was for years a member of the household of Chief Crazy Horse. He was also well acquainted with Sitting Bull and most other noted Indians of the north. Moreover, his many hunting forays with them gave him a familiarity with the whole Sioux country that fitted him perfectly for the demands of the military, if he could be wholeheartedly enlisted.[55]

Recruitment by General Crook

One day, Strahorn was in the private office of the post trader at Camp Robinson in the Red Cloud Agency, and a clerk suddenly thrust open the door and excitedly exclaimed: “A strange thing just happened. A man dressed and looking like an Indian was just outside the counter with a band of Indians who are in from Powder River. He was looking at a newspaper lying on the counter. Thinking it strange for an Indian to be reading, I started joshing him in Sioux. “Why are you looking at the paper, you can’t read, especially when it’s upside down?” He answered in good English, “It isn’t upside down, and I can read just as well as you!” “With that he dropped the paper, and acting as though he had not meant to give himself away, quickly rushed out.” Strahorn questioned some of the other Indians, and they said that was Frank Grouard, who had just sneaked in from the Crazy Horse camp for ammunition and supplies”[56] General Crook took a lively interest in the matter, and said: “By all means have the man followed quickly and if found brought in." It was no easy job to locate Frank Grouard among 5000 Indians as we found out later, if he didn’t want to be discovered. But it was done. He was brought in and proved to be the hero in the opening chapter of a real war romance. He was about twenty-five year old, six foot tall, finely built, with black hair, keen black eyes, and complexion much like an Indian. In fact, when he appeared in a blanket and other ordinary Indian trappings he readily passed for one. He was at first much averse to talking, and when General Crook had to some extent put him at his ease, he was still more averse to deserting his companions to join us. “You know what would happen if I turned against the Indians and Crazy Horse ever got sight of me.” “Well,” asked General Crook, “with the army behind you, don’t you think you would be safer than fighting us under Crazy Horse, who will be subdued and brought in, whatever the costs?” “Maybe, if the army would stay put, but what about it after the fight is over? That is my country. I know nothing else to do but live with the Indians. Crazy Horse would never forget.” “You have my word that we will find someway to take care of you if you give us the service you seem able to give.” After much parleying, Grouard said: “I’ll think it over and let you know.” “You promise not to leave the agency meanwhile?” asked the General. “Yes sir, I will see you first.”[57]

Grouard’s love interest

Strahorn learned of Grouard’s love for a white girl who had been taken to his camp and adopted. Long previous to the capture of Grouard, Indians had waylaid a wagon train bound from Cheyenne to Montana over the old Bozeman Road, killing all but one little white girl, who was taken to their camp and adopted. She had been taken so young and had been with them so long that by the time of Grouard’s capture she knew little of any other life. She and Grouard ultimately fell in love and they were due to be wed upon his present return from the agency where, in addition to ammunition, he was to gather up some simple articles desired for their settling down in a tepee their own. Here was a real dilemma, the most appealing solution was immediately return to the bride, which, however, meant war with Uncle Sam. On the other hand, engagement with General Crook meant war with his friend in the wilds and certain burning at the stake if ever captured by Crazy Horse. Grouard had much to “think over” beside the deadly enmity of Crazy Horse. He finally determined to cast his lot with Crook on the condition that the military would support him to the limit in capturing the girl. Then, if his services were found satisfactory, they were to provide some employment for a reasonable period after the war, pending his search for other means of obtaining a livelihood.[58]

Grouard's qualities

Strahorn admired Grouard. The acquisition of Grouard as scout and guide proved even more fortunate than it promised. Besides knowing the vast rough and generally traceless country so well that was to be the scene of a most difficult two years’ war that he could unfailingly find an objective even at night, he had every other desired quality. Brave as a lion, but never rash, with a physique so powerful as to endure almost unheard-of strain and hardship; a dead shot with rifle or revolver, and so loyal and unerring in his advice that General Crook learned to trust him utterly. Knowing every trait of the Indian as well as he knew himself, he proved invaluable. We later on had many scouts such as Buffalo Bill and others of newspaper notoriety, but never another like Frank Grouard. With it all, he was modest and reserved almost to a fault. We all learned to like and admire him, and at the close of the war, General Crook’s promise was made good. He was employed by the government in various capacities on the frontier in connection with Indian supervision, until his death many years later.”[59] Captain Bourke said: “Grouard was one of the most remarkable woodsmen I ever met. No Indian could surpass him in his acquaintance with all that pertain to the topography and animal life. No question could be asked him that he could not answer at once and correctly. His bravery and fidelity were never questioned; he never flinched under fire, and never growled at privation.”[60]

Captain Mills’s assault at Slim Buttes

Chief American Horse’s village

On September 7, 1876, General Crook ordered Captain Anson Mills to take 150 troopers, riding upon the command’s best horses, to the northernmost mining camps in the Black Hills to obtain food and supplies for his starving troops and hurry back. Accompanying Mills’s command were civilian scouts Grouard and Crawford, and newspaper correspondents Strahorn and Davenport.[61] Lieutenant John W. Bubb, the expedition commissary, had charge of sixteen packers and sixty-one pack mules.[62] Mills’s command left camp that same evening in “a thick mist,” guided by Grouard, Crook’s chief scout. About 1:00 a.m. the command stopped to rest, then moved on at daylight. On the afternoon of September 8, 1876, Grouard and Crawford and were ranging a mile or more in advance of Mills, and Grouard spied Indian hunters and ponies piled high with game.[63] Further investigation revealed the presence Oglala Lakota Chief American Horse’s village of Oglalas, Minneconjous, Brules and Cheyennes, numbering thirty-seven lodges and about 260 people, of whom 30 to 40 were warriors.[64] The village lay compactly in a broad depression of ravines encircled by the spires of Slim Buttes, limestone and clay summits capped with pine trees near present day Reva, South Dakota. Grouard and Crawford also found about 400 ponies grazing near the village. Tipis were clustered about the various ravines and streams that crisscrossed the natural amphitheater and smoke from the tipi fires hanging low beneath the misty clouds obscured the lodges. The village slept soundly in the cold rain.[65]

Battle plan

After learning of the village, Captain Mills sent Grouard on reconnaissance mission. Disguised as an Indian, Grouard, went through the village looking for the best point to attack.[66] After consulting his officers and scouts, Mills decided to conduct an assault. Captain Mill’s battle plan was the classic “dawn attack” in U.S. Army and Indian warfare. The goal was to surround the enemy, stampede and capture their stock, and kill as many of the warriors as possible.[67] On the evening of September 8, 1876, Captain Mills split his men into four groups to attack the village. Twenty-five were to remain hidden in a ravine a mile or so back, holding the horses and pack train.[68] Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka would lead twenty-five mounted soldiers in a cavalry charge through the clustered lodges and stampede the Indians and their pony herd, all hands yelling and firing with revolvers to add to the confusion. One hundred dismounted cavalrymen split in two groups would surround the village as nearly as possible, shoot the stampeded warriors as they emerged from their tipis and capture the ponies.[69] Lieutenant Emmet Crawford was ordered to post his fifty-seven troopers in skirmish order north and east of the camp, and Lieutenant Adolphus Von Luettwitz moved his fifty-three troopers east and south of the village.[70] Both groups would open fire on the lodges and close in on foot once Schwatka’s cavalry had routed the ponies and cleared the village area.

“On the night before the assault, Strahorn did not even attempt to sleep. Thorough the night he and others alternatively sat and stood, holding their horses in the cold rain and mist. “Never before or since,” he wrote in later years, “were hours so laggard or anxiety so great for the coming of dawn when we could do something that would heat the blood and cheer the soul to the forgetfulness of that everlasting, soaking, patter patter of freezing rain.”[71] However, before the full plan could be carried out, troopers startled the Indian pony herd and they stampeded through the village neighing the alarm to Indians, who cut their way out of tipis for an escape to the hills.[72] Since all chance for a total surprise was lost, Mills ordered the immediate charge with Schwatka and his twenty-five men.[73] Schwatka, joined by Grouard, Captain Jack and Strahorn thereupon charged and followed the ponies into the village firing pistols into the lodges.[74] “Immediately, the dismounted detachments closed on the south side and commenced firing on the Indians.”[75] “The fleeing warriors managed to unleash one or two volleys at the soldiers, and Lieutenant Van Luettwitz’s fell almost immediately, a bullet shattering his right kneecap as he stood on the knoll next to Mills. Instantly Captain Jack rushed over, tearing off the neckerchief he wore and fashioning a tourniquet about Van Luettwitz’s wounded leg to check the flow of blood.”[76] Taken by surprise the Indians fled. Strahorn recalled, “As usual, I could not be denied the thrill of the charge by the gallant twenty-five, and I’m sure that everything worked out as planned, except that many of the Indians escaped into a thicket in the bottom of a narrow gulch running along within a few yards of the nearest tepee, while a few others got away into the hills.[69] The Indians, finding themselves laced in their lodges, the leather drawn tight as a drum in the heavy rain, quickly cut themselves out with their knives and returned fire.[77] Many were seen to fall, and even in the approaching daylight it was often hard to tell whether the burdens carried were children or the slain and wounded.[78] The squaws carried the dead, wounded, and children up the opposite bluffs, leaving everything but their limited nightclothes in our possession.[79] Most of the Indians fled splashing through the swollen creek and scrabbling into the heavy underbrush south of the stream bed and up the adjacent bluffs, taking advantage of Mill’s failure to secure an effective cordon southwest of the tipis.

Entering the village

After the Indians withdrew, Strahorn, Captain Jack and about fourteen volunteers, mostly packers, entered the deserted village to survey its contents. A mule pack was taken along to secure dried meat found hanging from poles. Immediately, the mule was killed by a shot and the men fired upon from Indians concealed in the bluffs. Drawing cross fire, the men quickly jumped into the bed of a dry ravine.[80] Meanwhile, Captain Mills waited for a time, slowly entered the camp, and troopers were sent in groups through the village to check tipis and collect stores.[81] “The picture we quickly presented in our movements around the battle field with the skirmishing still in progress, rifles in one hand and ravenously chewing at a great hunk of dried meat in the other, provoked much fun, and, with blessed momentary sunshine, a general forgetfulness of past troubles.” Chief American Horse’s camp was a rich prize. “The lodges were full of furs and meat, and it seemed to be a very rich village. Crook seized and destroyed food, seized three or four hundred ponies, arms and ammunition, furs and blankets."[82] In a dispatch written for the Omaha Daily Bee, Crawford described the cornucopia he encountered: “Tepees full of dried meats, skins, bead work, and all that an Indian’s head could wish for.”[83] The troopers also captured about 300 fine ponies to partly replace their dead horses.[84] Of significance, troopers recovered items from the Battle of Little Bighorn, including a 7th Cavalry Regiment guidon from Company I, fastened to the lodge of Chief American Horse and the bloody gauntlets of slain Captain Myles Keogh.[85] “One of the largest of the lodges, called by Grouard the “Brave Night Hearts,” supposedly occupied by the guard, contained thirty saddles and equipment. One man found eleven thousand dollars in one of the tipis. Others found three 7th Cavalry horses; letters written to and by 7th Cavalry personnel; officers’ clothing; a large amount of cash; jewelry; government-issued guns and ammunition.[86]

Messengers to Crook

Promptly upon taking the village, Captain Mills sent two bareback riders to tell General Crook that he had a village and was trying to hold and needed assistance.[87] When Crook received word from Mills’s three messengers he could scarcely contain his anger at Mills.[88] Crook was primarily interested in feeding his men and ordered Mills to avoid a fight should he encounter a large village, and instead, “cut around it” and go into the Black Hills to get supplies.[89] Crook also told Mills that he expected to bivouac his exhausted men and therefore Mills could not expect any immediate support. Crook’s officers debated the propriety of Mills’s attack on a hostile village of uncertain size, a controversy intensified by Custer’s defeat under like circumstances. The question was especially provocative since Mills had opened the engagement with a small supply of ammunition.[90] Strahorn reported, “Crook was very much disappointed because Mills didn’t report his discovery last night, and there was plenty of time to have got the entire command there and so effectively surrounded the village that nothing would have escaped. But the General is also pleased, all things considered.”[91] Staff officers in telling the receipt of this news said Crook pushed the cavalry on with all possible haste, the infantry to follow more leisurely. But the tidings reaching Crook so electrified the immortal infantry that they forgot all about hunger, cold, wet and fatigue.[92] Fortunately for Mills, Crook’s column was not far behind.[93] Crook assembled a relief contingent of about 250 men and 17 officers, plus surgeons Bennett A. Clements and Valentine T. Mcgillycuddy.[94] John Frederick Finerty, war correspondent for the Chicago Times, joined the advance column. Despite the hardships of the Horsemeat March, the troopers were excited by the prospects of a battle.

Chief American Horse’s defiance

At the onset of the stampede and cavalry charge, Chief American Horse with his family of three warriors and about twenty-five women and children retreated into one of the ravines that crisscrossed the village amongst the tipis. The winding dry gully was nearly 20 feet deep and ran some 200 yards back into a hillside. Trees and brush obstructed the view of the interior. “We found that some of the Indians had got into a cave at one side of the village. One of the men started to go past that spot on the hill, and as he passed the place he and his horse were both shot. This cave or dugout was down in the bed of a dry creek. The Indian children had been playing there, and dug quite a hole in the bank, so that it made more of a cave than anything else, large enough to hold a number of people.”[95] Troopers were alerted about the ravine when Private John Wenzel, Company A, Third Cavalry, became the first army fatality at Slim Buttes when he ill-advisedly approached the ravine from the front and a Sioux bullet slammed into his forehead. Wenzel’s horse was also shot and killed. An attempt was made to dislodge the Indians and several troopers were wounded.[96] “Grouard and Big Bat Pourier crept close enough to the banks of the ravine to parley with the concealed Indians in endeavors to get them to surrender. But the savages were so confident of succor from Crazy Horse and his much larger force, who were encamped only a dozen miles to the west, and to whom they had sent runners early in the morning, that they were defiant to the last.” These Indians felt no urgent need to surrender, for they defiantly yelled over to the soldiers more Sioux camps were at hand and their warriors would soon come to free them. Chief American Horse, anticipating relief from other villages, constructed a dirt breastworks in front of the cave and geared for a stout defense.[97]

Indians regroup

Mills and Grouard soon realized a mistake had been made; Indians were firing back and the command was surrounded. After the firefight with Chief American Horse at the ravine, Mills sent yet another messenger, the third, to Crook. Mills decided against further efforts to expel the Indians and his men dug entrenchments facing the ravine.[98] As soon as the warriors had their squaws and children in security, they returned to the contest and soon encompassed Mills with a skirmish-line, whose command was engaged with the wounded and the held ponies. The Indians made several abortive rushes to recapture their ponies, and Strahorn reported that a number of the most gallant dashes were made at them by Lieut. Crawford at the head of ten or twelve cavalry. Observing warriors riding back and forth through the gaps in the buttes, Mills grew worried that there was another village nearby and that Crook may not arrive in time. Captain Mills gave the order to retreat, but Captain Jack told him that a retreat was impossible. Not anticipating an Indian fight, Mills had allowed his men only fifty rounds of ammunition each, and he would wait for General Crook’s personal attention to Chief American Horse.[99]

General Crook arrives

On September 9, 1876, General Crook’s relief column endured a forced march of twenty-miles to Slim Buttes in about four hours and a half hours arriving at 11:30 a.m. The whole cheering command entered the valley, and the village teemed with activity like an anthill which had just been stirred up.[100] Crook immediately established his headquarters and set up a field hospital in one of the Indian lodges.[101] Crook inventoried the camp and the booty. The camp held thirty-seven lodges. A three- or four-year-old girl was discovered, but no bodies were found. Over 5000 pounds of dried meat was found and was a “God-send” for the starved troopers.[102] Troopers separated the stores to be saved from the greater number to be destroyed, and the remaining tipis were pulled down.

The ravine at Slim Buttes

Crook soon turned his efforts to dislodging Chief American Horse and his family in the ravine. The defenders had already killed Private John Wenzel, wounded others and threatened all that approached. The deaths and injuries of their comrades inflamed the soldiers who were already distraught from their ordeal. Trees and brush obstructed the view of the interior of the winding dry gully and the narrowness kept the soldiers from firing accurately. Some of the scouts and packers joined in an informal attempt to roust the Indians but met with unexpected firepower and fell back in surprise.[104] “Crook then deployed troops below the mouth of the ravine, crawling on their bellies, firing at random into the hidden ravine without evident harm to the warriors. Before long a multitude of soldiers had gathered near the cavelike mouth of the ditch, somewhat protected from gunfire by sharp embankment. Officers and men joined sending a fusillade into its black depths, and suddenly they received a veritable volley in response that sent them reeling and stumbling away.”[105] Then, on Crook’s orders, First Lieutenant William Philo Clark led a group of twenty volunteers forth, but the Indians sent forth such overwhelming volleys that the troops scampered for safety.[106] Some of the men crept forward with flaming sticks which they tossed into the ditch without apparent effect. By now hundreds of idlers had gathered in the vicinity of the ravine and they complicated the efforts. “It was a wonder to me,” recalled Major John G. Bourke, "that the shots of the beleaguered did not kill them by the half-dozen.”[107]

Charles “Buffalo Chips” White

Crook’s scouts positioned themselves on the opposite side of the ravine just above the cave. The bank of the ravine was probably eight to ten feet high, and the scouts could converse with the Indians below without the danger of getting shot.[108] After Lieutenant Clark’s unsuccessful assault, Scout Charles "Buffalo Chips" White attempted to get a shot in the cave and was immediately killed by the defenders. Frank Grouard witnessed the incident: "Buffalo Chips was standing opposite me. He was one of those long-haired scouts, and claimed to be a partner of Buffalo Bill's. He thought it was a good place to make name for himself, I suppose, for he told Big Bat that he was going to have one of the Indians' scalps. He had no more than got the words out of his mouth before he yelled, “My God, I am shot." I heard this cry and looked around, Buffalo Chips was falling over into the hole where the Indians were hiding. Bat was looking into the cave where the Indians were, and about five seconds afterwards jumped out with an Indian’s scalp in his hand, telling me that he had scalped one of the redskins alive, which I found out to be true. He had seen the Indian that killed Buffalo Chips, and he jumped down onto him as the Indian was reaching to get White’s six-shooter. Bat had jumped right down on top of him and scalped him and got out of the cave before anybody knew what he was doing."[109] "Buffalo Chips" White was a boyhood friend of Col. Cody and also a scout. He wanted to be like Buffalo Bill and acquired the sobriquet "Buffalo Chips" when Gen. Phillip Sheridan said he was more like Buffalo Chips than Buffalo Bill. Major Bourke described him as a "good-natured liar who played Sancho Panza to Buffalo Bill's Don Quixote."[110] Gen. Charles King said Buffalo Chips was a "good man."[111]

Women and children

“Crook, exasperated by the protracted defense of the hidden Sioux, and annoyed at the casualties inflicted among his men, formed a perfect cordon of infantry and dismounted cavalry around the Indian den. The soldiers opened upon it an incessant fire, which made the surrounding hills echo back a terrible music.”[112] “The circumvalleted Indians distributed their shots liberally among the crowding soldiers, but the shower of close-range bullets from the latter terrified the unhappy squaws, and they began singing the awful Indian death chant. The papooses wailed so loudly, and so piteously, that even not firing could not quell their voices. General Crook ordered the men to suspend operations immediately, but dozens of angry soldiers surged forward and had to be beat back by officers.[112] “Neither General Crook nor any of his officers or men suspected that any women and children were in the gully until their cries were heard above the volume of fire poured upon the fatal spot.”[113] Crook Grouard and Pourier, who spoke Lakota, were ordered by General Crook to offer the women and children quarter. This was accepted by the besieged, and Crook in person went into the mouth of the ravine and handed out one tall, fine looking woman, who had an infant strapped to her back. She trembled all over and refused to liberate the General’s hand. Eleven other squaws and six papooses were taken out and crowded around Crook, but the few surviving warriors refused to surrender and savagely re-commenced the fight.”[114]

“Rain of hell”

Chief American Horse refused to leave, and with three warriors, five women and an infant, remained in the cave. Exasperated by the increasing casualties in his ranks, Crook directed some of his infantry and dismounted cavalry to form across the opening of the gorge. On command, the troopers opened steady and withering fire on the ravine which sent an estimated 3000 bullets among the warriors.[115] Finerty reported, “Then our troops reopened with a very ‘rain of hell’ upon the infatuated braves, who, nevertheless, fought it out with Spartan courage, against such desperate odds, for nearly two hours. Such matchless bravery electrified even our enraged soldiers into a spirit of chivalry, and General Crook, recognizing the fact that the unfortunate savages had fought like fiends, in defense of wives and children, ordered another suspension of hostilities and called upon the dusky heroes to surrender.”[116] Strahorn recalled the horror. “The yelling of Indians, discharge of guns, cursing of soldiers, crying of children, barking of dogs, the dead crowded in the bottom of the gory, slimy ditch, and the shrieks of the wounded, presented the most agonizing scene that clings in my memory of Sioux warfare.”[97]

Surrender of Chief American Horse

When matters quieted down, Grouard and Pourier asked American Horse again if they would come out of the hole before any more were shot, telling them they would be safe if they surrendered. “After a few minutes deliberation, the chief, American Horse, a fine looking, broad-chested Sioux, with a handsome face and a neck like a bull, showed himself at the mouth of the cave, presenting the butt end of his rifle toward the General. He had just been shot in the abdomen, and said in his native language, that he would yield if the lives of the warriors who fought with him were spared.[117] Pourier recalled that he first saw American Horse kneeling with a gun is his hand in a hole on the side of the ravine that he had scooped out with a butcher knife. Chief American Horse had been shot through the bowels and was holding his entrails in his hands as he came out. Two of the squaws were also wounded. Eleven were killed in the hole.[118] Grouard recognized Chief American Horse, “but you would not have thought he was shot from his appearance and his looks, except for the paleness of his face. He came marching out of that death trap as straight as an arrow. Holding out one of his blood-stained hands he shook hands with me.”[119] When Chief American Horse presented the butt end of his rifle, General Crook, who took the proffered rifle, instructed Grouard to ask his name. The Indian replied in Lakota, “American Horse.”[115] Some of the soldiers, who lost their comrades in the skirmish shouted, “No quarter!’, but not a man was base enough to attempt shooting down the disabled chief. Crook hesitated for a minute and then said,‘Two or three Sioux, more or less, can make no difference. I can yet use them to good advantage. "Tell the chief,“ he said turning to Grouard, "that neither he nor his young men will be harmed further.”[117] “This message having been interpreted to Chief American Horse, he beckoned to his surviving followers, and two strapping Indians, with their long, but quick and graceful stride, followed him out of the gully. The chieftain’s intestines protruded from his wound, but a squaw, his wife perhaps, tied her shawl around the injured part, and then the poor, fearless savage, never uttering a complaint, walked slowly to a little camp fire, occupied by his people about 20 yards away, and sat down among the women and children.” [120]

Chief American Horse was examined by the two surgeons. One of them pulled the chief’s hands away, and the intestines dropped out. “Tell him he will die before next morning,” said the surgeon.[121] The surgeons worked futilely to close his stomach wound, and Chief American Horse refused morphine, preferring to clench a stick between his teeth to hide any sign of pain or emotions and thus he bravely and stolidly died.[97] Chief American Horse lingered until 6:00 a.m. and confirmed that the tribes were scattering and were becoming discouraged by war. “He appeared satisfied that the lives of his squaws and children were spared.”[122] Dr. McGillicuddy, who attended the dying chief, said that he was cheerful to the last and manifested the utmost affection for his wives and children. American Horse’s squaws and children were allowed to remain on the battleground after the dusky hero’s death, and subsequently fell into the hands of their own people. Even “Ute John” respected the cold clay of the brave Sioux leader, and his corpse was not subjected to the scalping process.”[123] Crook was most gentle in his assurances to all of them that no further harm should come if they went along peacefully, and it only required a day or two of kind treatment to make them feel very much at home.[97]

Crazy Horse attacks

Indians who escaped Mills’ early morning assault spread the word to nearby Lakota and Cheyenne camps, and informed Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and other leaders they were attacked by 100–150 soldiers. Crazy Horse immediately assembled 600–800 warriors and rode about ten miles northward to rescue Chief American Horse and recover ponies and supplies.[124] During the afternoon Chief American Horse and some of the squaws informed Gen. Crook, through the scouts, that Crazy Horse was not far off, and that we would certainly be attacked before nightfall.[125] “In anticipation of that afternoon tea party which was promised to be given by Crazy Horse, Crook deployed his forces to give that chieftain the surprise of his life. Concealing the major portion in the ravine in up-to-the-minute readiness and eagerness for an attack, he deployed just enough of the boys in plain sight to carry out the impression that the Indian couriers had conveyed to Crazy Horse, that only about a hundred soldiers would be found to oppose his eager and confident large reinforcements.”[126] As a grave was being dug for Private Wenzel, and the starved troopers were ready to dine on captured bison meat, rifle shots were heard from the bluffs above and around the camp.[127] Crook immediately ordered the village to be burned. “Then followed the most spectacular and tragically gripping and gratifying drama of the whole Sioux War, enacted with a setting and view for those of us in the ambushing corps that could not be improved upon. The huge amphitheater, leading from our position in the front orchestra row, up over a gradually rising terrain to the rim of the hills which surrounded on three sides, was not unlike the situation which Crazy Horse had chosen for his Battle of the Rosebud.”[128] Finerty tells how the Indians attacked. “Like the Napoleonic cuirassiers at Waterloo, they rode along the line looking for a gap to penetrate. They kept up perpetual motion encouraged by a warrior, doubtless Crazy Horse himself, who, mounted on a fleet, white horse, galloped around the array and seemed to possess the power of ubiquity.”[129] Strahorn reported, “Suddenly the summits seemed alive with an eager expectant and gloating host of savages who dashed over and down the slope, whooping and recklessly firing at every jump.”[128]

Crook’s tea party

Crazy Horse was surprised to find American Horse’s village massed with Crook's main column of over 2000 infantry, artillery, cavalry and scouts.[130] “Crazy Horse so little dreamed of the heavy reinforcements of Captain Mills’ small band that, in the utmost confidence of ‘eating us alive’ he launched his followers right down upon the front and flanks of out splendid defensive position. They were permitted to approach with blood curdling whoops and in a savage array within easy and sure fire rifle range before the order to fire was given. They reacted to the deadly shock in a manner that was the real beginning of the end of the Sioux War, so far as any major performance of Crazy Horse was concerned. Bewildered and demoralized by the well-aimed volleys of our two-thousand guns, they dashed for cover in every direction, closely followed by details of our boys who were allotted that much sought privilege.”[131] “Failing to break into that formidable circle, the Indians, after firing several volleys, their original order of battle being completely broken, and recognizing the folly of fighting such an outnumbering force any longer, glided away from our front with all possible speed. As the shadows came down into the valley, the last shots were fired and the affair at Slim Buttes was over.”[132]

Prisoners, bodies and scalpings

One of the two remaining warriors from the ravine was Charging Bear, who later became a U.S. Army Indian Scout.[133] They had twenty-four cartridges remaining among them, and bodies had been used as shields. Finerty wrote that “the skull of one poor squaw was blown, literally, to atoms, revealing the ridge of the palate and presenting a most ghastly and revolting spectacle. Another of the dead females was so riddled with bullets that there appeared to be no unwounded part of her person left.”[134] Crook ordered the remaining bodies removed from the cave. “Several soldiers jumped at once into the ravine and bore out the corpses of the warrior killed by Pourier and three dead squaws.”[135] “The old Indian Big Bat Pourier had killed was unceremoniously hauled up by what hair remained and a leather belt around the middle. The body had stiffened in death in the posture of an old man holding a gun, which was the way he shot. He was an old man, and his features wore a look of grim determination.”[136] “Ute John scalped all of the dead, unknown to the General or any of the officers, and I regret to state a few, a very few, brutalized soldiers followed his savage example. Each took only a portion of the scalp, but the exhibition of human depravity was nauseating. The unfortunate should have been respected, even in the coldness and nothingness of death. In that affair surely the army were the assailants and the savages acted purely in self defense.”[137] Even “Ute John” respected the cold clay of the brave Sioux leader Chief American Horse and his corpse was not subjected to the scalping process.”[138] Captain Jack told readers of the Omaha Daily Bee that he had taken “one top-knot” during the Battle of Slim Buttes in which he “came near losing” his own hair. He later regretted the bloody deed and never spoke of it in public performances.[139]

Casualties

Captain Mills reported the assault: “It is usual for commanding officers to call special attention to acts of distinguished courage, and I trust the extraordinary circumstances of calling on 125 men to attack, in the darkness, and in the wilderness, and on the heels of the late appalling disasters to their comrades, a village of unknown strength, and in the gallant manner in which they executed everything requited of them to my entire satisfaction.”[140] U.S. Army casualties were relatively light with a loss of 30 men: 3 killed, 27 wounded, some seriously.[141] Because the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors maintained a distance of five to eight hundred yards, and consistently fired their weapons high, casualties were few.[142] Those who died in the field were Private John Wenzel, Private Edward Kennedy and Scout Charles “Buffalo Chips” White.”[143] Private Kennedy, Company C, Fifth Cavalry, had half the calf of his leg blown away in a barrage, and throughout the night medical personnel labored to save his life. Private Kennedy and Chief American Horse died in the surgeons’ lodge that evening.[144] Lt. Von Luettwitz had his shattered leg amputated above the knee and Private John M. Stevenson of Company I, Second Cavalry, received a severe ankle wound at the ravine. “The Indians must have lost quite heavily. Several of their ponies, bridled but riderless, were captured during the evening. Indians never abandon their war horses, unless they happen to be surprised or killed. Pools of blood were found on the ledges of the bluffs, indicating where Crazy Horse’s warriors paid the penalty of their valor with their lives.”[145] Reports of Indian casualties varied, and many bodies were carried away. Sioux confirmed casualties were at least ten dead, and an unknown number wounded. About 30 Sioux men, women and children were in the ravine with Chief American Horse when the firefight began, and 20 women and children surrendered to Crook.[146] Ten individuals remained in the ravine during the 'rain of hell' and five were killed; Iron Shield, three women, one infant and Chief American Horse who died that evening. The rest were made prisoners.[147] Charging Bear resisted most desperately and was finally dragged out of his lair at the bottom of the deep gully with only one cartridge left. Marched here as a prisoner, he soon after enlisted with General Crook, exhibiting great prowess and bravery on behalf of his new leader and against his former comrades.”[148]

Victory of the battle

A rich prize

Chief American Horse’s camp was a rich prize. “It was the season when the wild plums ripen. All the agency Sioux were drifting back to the agencies with their packs full of dried meet, buffalo tongues, fresh and dried buffalo berries, wild cherries, plums and all the staples and dainties which tickled the Indian palate.”[149] The lodges were full of furs and meat, and it seemed to be a very rich village. Crook seized and destroyed food, seized three or four hundred ponies, arms and ammunition, furs and blankets.[150] In a dispatch written for the Omaha Daily Bee, Crawford described the cornucopia he encountered: “Tepees full of dried meats, skins, bead work, and all that an Indian’s head could wish for.”[83]

Of significance, troopers recovered items from of the Battle of Little Bighorn, including a 7th Cavalry Regiment guidon from Company I, fastened to the lodge of Chief American Horse and the bloody gauntlets of slain Captain Myles Keogh.[85] “One of the largest of the lodges, called by Grouard the “Brave Night Hearts,” supposedly occupied by the guard, contained thirty saddles and equipment. One man found eleven thousand dollars in one of the tipis. Others found three 7th Cavalry horses; letters written to and by 7th Cavalry personnel; officers’ clothing; a large amount of cash; jewelry; government-issued guns and ammunition.[86]

The victory campfire

Crook’s command showed great endurance and courage during the Horsemeat March, and the first victory after the Little Big Horn was morale raising for hungry troops. That evening the starved and exhausted troopers in General Crook’s camp celebrated, ate and sang. Custer and the 7th Cavalry had been avenged and Oglala Lakota Chief American Horse mortally wounded. One reporter wrote: “Night is here, and 1,000 camp-fires light a scene never to be forgotten. The soldiers last night, ragged, cold, weak, starved and well-nigh desperate, are feasting upon meat and fruits received from a savage enemy, and warmly clothed by the robes which last night wrapped the forms of renegades. Merry songs are sung, and everywhere goes up the cry, Crook is right after all.”[151] Crawford told readers of the Omaha Daily Bee that “a good night’s rest, on ground high and dry, with plenty of buffalo robes, blankets and big fire, was the result of our day’s labor.”[152] “As we were gathered around the campfires, still chewing the hard and tough meat, all of course after the captured Indians had fully regained their composure, several broke out in, for them, a most unusual laugh. We asked Frank Grouard to find out what it was all about. One of them asked him what kind of meat we thought we were eating. He answered we supposed it was dried buffalo meat and venison. Their spokesman replied that we had kept them on the run so long that they had no chance to kill or save any such game. “Well, then, what is it?” Grouard asked. The answer came with another general laugh: “That was the ponies that died.” Well, they didn’t have so much at that, for ours before was from horses that had almost died.” [153] “As darkness approached, with the enemy driven in confusion for miles as long as a live one remained in sight, our rejoicing boys straggled back, the firing ceased, as we settled down in that night’s rain with more complacency over a day’s work well done and more comfort, upon fuller stomachs, augmented by our use of the spoils of war, than we had enjoyed for many days.”[128]

War trophies

Crawford obtained American horse’s rifle, a Spencer repeater, along with a Colt revolver. Crawford also became the proud owner of a mare and colt, his share of the captured pony herd, distributed among the men who had charged the village.[154] During the campaign, Crawford told readers of the Omaha Daily Bee that he had taken “one top-knot” during a fight in which he “came near losing” his own hair. He later regretted his bloody deed and never spoke of it in his public performances.[155] In fact, he never portrayed himself as a great Indian killer but rather as a trail-smart scout risking his life in a hostile and dangerous environment.”[155]

General Crook’s departure from Slim Buttes

Private Wenzel’s burial, which had been interrupted by Crazy Horse’s afternoon counter attack, was completed Saturday night.[144] On early Sunday morning, September 10, 1876, the burial of Scout Charles ”Buffalo Chips” White and Private Edward Kennedy took place. The bodies were interred in one grave, along with Lieutenant Von Luettwitz’s leg.[156] “The bodies of the Indians, both male and female, were left where they fell so that their friends might have the privilege of properly disposing of them after we had left. The Sioux Indians, so far as known, never place their dead in the earth, so that leaving the bodies above ground was of no particular consequence in their case.”[157] Crook lectured his captives on the determination of the government to punish all those who remained hostile, and then announced his intention to free them the next day.[144] Crook then led his command away from Chief American Horse’s smoldering village headed for the Black Hills for supplies and rest.

Celebrations in the Black Hills

“Strahorn had his mouth set for food, and satisfied his personal needs immediately after they arrived in Crook City in Whitewood Canyon on the evening of September 12. Painfully, he slipped out of his saddle in front of a restaurant in that mining camp, entered, and faintly asked the waiter, ‘Could you possibly serve a beefsteak and a baked potato?’ The waiter obliged. ‘With elbows on the counter and my head dropping down between my hands,” he remembered, ‘I uttered a sigh of relief that meant so much it may have echoed round the world.’”[158] “It was not surprising that Crook’s expedition was looked upon as the savior of everything most dear and that the most extravagant of thanksgiving celebration was inaugurated and continued for several days. The thousands of flotsam and jetsam crowding the narrow, crooked streets and the more substantial occupants of the rows of wooden buildings lining them simply went wild as we rode through the towns. Firing of salutes with powder-charged anvils, ringing of bells, blowing of whistles, and uproarious yelling of the populace finally gave way to a great reception at the Deadwood Theatre. There were speeches by Crook and leading citizens, who handed him a long petition for continued military protection, with many other hospitable events in usual frontier styles, to impress us that the town was ours.”[159]

Captain Jack’s ride

.

On September 10, 1876, General Crook Crook ordered Frank Grouard, his trusted Chief Scout, to carry dispatches to Fort Laramie announcing the battle and victory at Slim Buttes. Grouard’s strict orders were to see that the official dispatches were telegraphed first, then followed by the dispatches from the war correspondents. The next morning, Grouard left in company with Captain Anson Mills, Lieut. Bubb and about seventy-five mounted troopers riding ahead to the Black Hills mining camps to purchase provisions for Crook’s command. At Crook’s request, Captain Jack joined Mills’s party, accompanied by war correspondents Robert E. Strahorn and Reuben Briggs Davenport. Unknown to Grouard, Davenport wanted an exclusive for the New York Herald and offered to pay Captain Jack five-hundred dollars if he could beat Grouard to the telegraph in Fort Laramie. Telegraphing news of the victory of Slim Buttes thus became a race between Frank Grouard and Captain Jack Crawford. It was a dangerous undertaking, for Indians were still harassing the mining communities, and only two days earlier, a Sioux party had come within two hundred yards of the main street in Crook City.[160]

On the morning of September 12, 1876, a small detail galloped into Crook City, with Captain Jack leading the way and quickly purchased supplies from citizens anxious to cooperate with the army. That evening while Grouard slept, Captain Jack embarked upon a daring ride racing ahead to Deadwood in the pitch dark.[161] The next day, when Grouard arrived in Deadwood, he learned that Captain Jack had arrived in Deadwood at 6 a.m., secured a new horse, and then headed for Custer City. Grouard quickly purchased fresh mounts and caught up with Captain Jack near Custer City. “The animal he was riding was completely winded. I asked him as soon as I caught up with him if he had not had orders to go with Lieut. Bubb to buy supplies. He made the reply that he was taking some dispatches through for the New York Herald.” Grouard told Captain Jack that “he was discharged from the time he quit the command.”[162] They agreed to spend the night in Custer City and resume the race the next day. Grouard had changed horses six times on the road, killing three and “using three of them up so they never were any good afterwards.” Upon his arrival in Custer City, he was so exhausted that he had to be taken off his horse. After handing the dispatches over to U.S. Army couriers, Grouard wrote a note to Gen. Crook telling him what he had done and laid in bed for three days. On September 16, 1876, Captain Jack reached Fort Laramie at 7:00 p.m., nine hours behind a government courier. Crawford had ridden a distance of 350 miles in six days. Still, Crawford had Davenport’s dispatches on the wire five hours ahead of all other correspondents. On September 18, 1876, the New York Herald published Crawford's own story under the headline “Captain Jack’s Ride as a Bearer of Herald Despatches.” While, the adventure cost Captain Jack his job as a military scout, his daring ride to tell the news of the great victory at Slim Buttes made him a national celebrity. Captain Jack proudly described his feat to countless audiences in later years.[163]

Press reports

Crook’s campaign drew both praise and scorn. The New York Times reported: “The general impression in this command is that we have not much to boast about in the way of killing Indians. They kept out of the way so effectively that the only band which was struck was struck by accident, and when, by the subsequent attack upon us, it was discovered that another and much larger village was not far off, the command was in too crippled and broken down a condition from starvation and overmarching to turn the information to any account.”[164] But Eastern tabloids so accustomed to reporting military setbacks, headlined the success. “Squaw Scalps,” elated the Chicago Times edition of September 17. Terming Mills’s dawn assault a “A Siouxprise” the paper told how “American Horse, Mortally Wounded, Gives his View of the Sioux Situation.” The Chicago Tribune headlined its coverage of the ravine fight with “He-Fiends, She-Fiends and Imps Driven into a Gulch and Mostly Killed.” The Chicago Times reported that American Horse lingered until 6:00 a.m. and that he confirmed that the tribes were scattering and were becoming discouraged by war. “He appeared satisfied that the lives of his squaws and children were spared.”[122] Strahorn reported: “This Slim Buttes battle is emphatically the event of the campaign so far as punishment for the Indians is concerned, and the participants under General Crook deserve the lasting thanks of our people, for without a doubt the den of redskins so thoroughly rooted out has furnished shelter for more than one of the plundering savages who have annoyed us recently.”[165] Finerty reported: “All other commanders had withdrawn from pursuit, but Crook resolved to teach the savages a lesson. He meant to show that neither distance, bad weather, the loss of horses not the absence of rations could deter the American Army from following up its wild enemies to the bitter end.”[166]

General Sheridan’s opinion