Black lion tamarin

| Black lion tamarin[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black lion tamarin at Bristol Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Callitrichidae |

| Genus: | Leontopithecus |

| Species: | L. chrysopygus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leontopithecus chrysopygus (Mikan, 1823)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

ater Lesson, 1840 | |

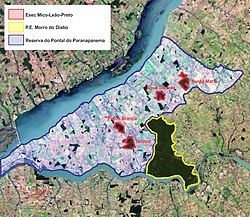

The black lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysopygus), also known as the golden-rumped lion tamarin, is a lion tamarin endemic to the Brazilian state of São Paulo, almost exclusively at the Morro do Diabo State Park. Its limited geographical range makes it the rarest of the New World monkeys, with little known about it.[4] It was thought to be extinct for 65 years until its rediscovery in 1970.[5] In 2016 an adult couple was found to the east, in the Caetetus Ecological Station, after six years with no sightings.[6]

The total number of individuals is estimated to be around 1000.[5] Some experts believe this to be an overestimate, as recent studies have shown that the average area inhabited by the black lion tamarin is closer to 106 hectares (260 acres) than the previously estimated 66 hectares (160 acres).[5] They are usually found in groups of 4 to 9, living in the secondary and primary forests along the circumference of its home range.

On average, the black lion tamarin weighs 590–640 grams (21–23 oz).[7]

Diet

The diet of the black lion tamarin is seasonal and varies with the habitats it moves through.[5] When the tamarin is in the dryland forest, it usually eats a variety of fruits, whereas in a swampy environment it predominantly feeds on the gum of various trees.[5] In addition to seasonal variation, the black lion tamarin exhibits daily and monthly cycles of food preferences.[8]

Independent of the environment it occupies, a tamarin spends long periods each day searching for different types of insects and spiders to feed on. On average, 80% of its time foraging is spent searching for insects,[5] such as by foraging the forest floor. The tamarin's foraging locations are very intentional: it spends extended periods of time looking under dry palm leaves, in loose bark, and in tree cavities, with hands that have specialized fingers for prying.[3] The tamarin also positions itself in trees and scans for insects from above, usually four meters above the forest floor.

The black lion tamarin eats the gum and fruit of trees, climbing up to ten meters to reach them and as these are easily found, the tamarin spends 12.8% of its day obtaining them, rather than the 41.2% of the day spent foraging for insects in the high trees.[5]

Offspring

Black lion tamarins mate and have offspring during the spring, summer, and fall months (August to March in Brazil).[9] Females usually have one litter per year, though 20% females produce two litters per year.[9] The mean litter size is two infants.[9]

Most mammals produce a 50:50 ratio of males to females. The black lion tamarin population almost always produce a 60:40 male to female ratio.[9]

Most infants deaths occur within the first two weeks of birth, with newborns of first-time mothers having the lowest survival rates. The number of tamarins that survive to adulthood in the wild is 10% higher than those in captivity.[9]

Food sharing

During the first few months after birth, the infant is unable to obtain food on its own. For this reason, the infant rides on the parent's back and receives food from the parents. It drinks milk in the 4 to 5 weeks after birth; after that, the parents and other group-members share food with the infant. Sharing involves both offers from the parents and begging by the infant. Usually, until the age of approximately 15 weeks, the infant will receive the majority of its food (especially insects) from others.[10] The number of offers from group-members peaks at week 7; after week 15, sharing slowly declines, stopping by week 26.[10]

Communication

Within Leontopithecus, the black lion tamarin is the largest in size and has the lowest-pitched calls, using longer notes than other species.[4] The black lion tamarin use calls to defend territory, maintain cohesion within the group, attract a mate, and contact individuals who might be lost. Most calls can be recorded in the morning, and can be attributed to the reunion of mated pairs. These mated pairs are coupled-up throughout the mating season.[clarification needed]

Taxonomy

The classification of the black lion tamarin was debated, as one group of taxonomists classified the lion tamarins by their geography, while other taxonomists placed them all into one species and then divided them into subspecies. More recently, taxonomists have agreed to base classification predominantly on their geography, though sometimes characteristics such as long calls are used to classify different species, similar to the use of bird songs in taxonomy.[4] For differentiating within Leontopithecus, the black lion tamarin is categorized as starting its call at the lowest note and going through the greatest range of pitch.[4]

Status and threats

The black lion tamarin is the most endangered species within Leontopithecus, and the IUCN has recorded their population to be declining.[11] The main threat against it is the destruction of its habitat through deforestation,[5] though it is also threatened by being hunted in unprotected forests, such as the Fazenda Rio Claro and the Fazenda Tucano (which have roughly 3.66 and 1.0 individuals per square kilometer respectively).[11]

There have been several attempts to bring black lion tamarins into captivity and to salvage what little habitat they have left within the Morro do Diabo State Park, as well as to increase breeding rates. Their population decline in the wild, however, could cause the black lion tamarins to become entirely endemic to the Morro do Diabo.

References

- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Rylands, A.B.; Mittermeier, R.A. (2009). "The Diversity of the New World Primates (Platyrrhini)". In Garber, P.A.; Estrada, A.; Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Heymann, E.W.; Strier, K.B. (eds.). South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Springer. pp. 23–54. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- ^ a b Kierulff, M. C. M.; Rylands, A. B.; Mendes, S. L.; de Oliveira, M. M. (2008). "Leontopithecus chrysopygus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. IUCN: e.T11505A3290864. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T11505A3290864.en. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Snowdon, Charles T.; Hodun, Alexandra; Rosenberger, Alfred L.; Coimbra-Filho, Adelmar F. (1 January 1986). "Long-call structure and its relation to taxonomy in lion tamarins". American Journal of Primatology. 11 (3): 253–261. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350110307.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Albernaz, Ana L. K. M. (1 January 1997). "Home Range Size and Habitat Use in the Black Lion Tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysopygus)". International Journal of Primatology. 18 (6): 877–887. doi:10.1023/A:1026387912013.

- ^ Mico-leão-preto ressurge na Estação Ecológica Caetetus (in Portuguese), Fundação Florestal, 8 September 2016, retrieved 2017-02-21

- ^ "Black lion tamarin (Leontopithecus chrysophygus)". ARKive. Environmental Agency – Abu Dhabi.

- ^ Camargo Passos, Fernando De; Keuroghlian, Alexine (1999). "Foraging Behavior and Microhabitats Used by Black Lion Tamarins, Leontopithecus Chrysopygus" (PDF). Revista Brasileira De Zoologia. 16: 219–222. doi:10.1590/s0101-81751999000600022.

- ^ a b c d e French, Jeffrey A.; Pissinatti, Alcides; Coimbra-Filho, Adelmar F. (1 January 1996). "Reproduction in captive lion tamarins (Leontopithecus): Seasonality, infant survival, and sex ratios". American Journal of Primatology. 39 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1996)39:1<17::AID-AJP2>3.0.CO;2-V.

- ^ a b Feistner, Anna T.; Price, Eluned C. (September 2000). "Food sharing in black lion tamarins (Leontopithecus chrysopygus)". American Journal of Primatology. 52 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1002/1098-2345(200009)52:1<47::AID-AJP4>3.0.CO;2-D. PMID 10993137.

- ^ a b Cullen, L.; Bodmer, E.R.; Valladares-Padua, C. (4 April 2001). "Ecological consequences of hunting in Atlantic forest patches, Sao Paulo, Brazil". Oryx. 35 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3008.2001.00163.x.

External links

Gallery

-

Black lion tamarin at Adelaide Zoo