Black mamba: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Black.mamba691 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

No edit summary Tag: Mobile edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{automatic taxobox |

{{automatic taxobox |

||

| name = Black mamba |

| name = Black mamba (Brandon Nii) (stop changing the fucking name) |

||

| taxon = Dendroaspis polylepis |

| taxon = Dendroaspis polylepis |

||

| image = Dendroaspis polylepis by Bill Love.jpg |

| image = Dendroaspis polylepis by Bill Love.jpg |

||

Revision as of 03:19, 28 May 2014

| Black mamba (Brandon Nii) (stop changing the fucking name) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Dendroaspis polylepis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendroaspis polylepis | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

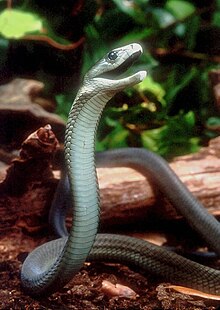

The black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), also called the common black mamba or black-mouthed mamba, is a highly venomous snake of the genus Dendroaspis (Mambas), and is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. It was first described in 1864 by Albert Günther. It is the longest species of venomous snake in Africa, and the second-longest venomous snake in the world after the King cobra. It is also the fastest moving snake in Africa, and one of the fastest moving snakes on the planet, perhaps the fastest.[4][5][6] Capable of moving at 11 km/h (6.8 mph) over a distance of 43 m (141 ft).

The venom of the black mamba is highly toxic. Based on the median lethal dose (LD50) values in mice, the black mamba LD50 is 0.28/0.32 mg/kg subcutaneous.[7][8][9] Although there are other venomous snakes that exhibit higher LD50 toxicity scores, its venom is one of the most rapid-acting. In cases of severe envenomation, it is capable of killing an adult human in as little as 20 minutes. Two such cases have been documented in the medical literature. In one such case, an adult male was bitten on his right arm, just above the wrist by a black mamba which was estimated to be approximately 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in length. The victim began to show signs of prominent neurotoxicity within minutes. At ten minutes post-envenomation, respiratory paralysis set in and 20 minutes post-envenomation the victim showed no signs of life and was deceased.[10] Other cases of rapid death, within 30–60 minutes are relatively common among this species. However, depending on the nature of the bite, death time can be anywhere from 20 minutes to 6–8 hours. Without rapid and vigorous antivenom therapy, a bite from a black mamba is rapidly fatal almost 100% of the time.[11] One snake expert called this species "death incarnate",[12] to South African locals the black mamba bite is known as the "kiss of death".[13]

The black mamba is considered the most dangerous and feared[14] snake in Africa, though the ocellated carpet viper is responsible for more human fatalities due to snakebite than all other African species combined.[15] According to wildlife biologist Joe Wasilewski, black mambas are the most-advanced of all the snake species in the world. Their venom apparatus and method of delivering venom is also probably the most-effective and most-evolved among all venomous snakes.[16] Its combination of speed, unpredictable aggression, and potent venom make it an extremely dangerous species. The black mamba has a reputation for being very aggressive, but like most snakes, it usually attempts to flee from humans unless threatened.

Many experts regard the black mamba and the coastal taipan as the world's most dangerous snakes.

Taxonomy

The eastern green mamba, Dendroaspis angusticeps, and the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis were considered a single species until 1946 when Dr. Vivian FitzSimons split them into separate species.[17]

Etymology

The snake's scientific name is Dendroaspis polylepis: Dendroaspis meaning "tree asp", and polylepis meaning "many-scaled." The name "black mamba" is given to the snake not because of its body colour but because of its ink-black mouth.[18] It displays this physical attribute when threatened.[18]

Description

The black mamba's back skin colour is olive, brownish, gray, or sometimes khaki.[19] The adult snake's length is on average 2.5 meters (8.2 ft),[18] but some specimens have reached lengths of 4.3 to 4.5 meters (14 to 15 ft).[19] Black mambas weigh about 1.6 kilograms (3.5 lb).[18] on average. The species is the second longest venomous snake in the world, exceeded in length only by the king cobra.[19] The snake has an average life span of 11 years in the wild.[18]

Distribution

The black mamba lives in Africa, occupying the following range: Northeast Democratic Republic of the Congo, southwestern Sudan to Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Eastern Uganda, Tanzania, southwards to Mozambique, Swaziland, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and Namibia; then northeasterly through Angola to southeastern Zaire.[20] The black mamba is not commonly found above altitudes of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), although the distribution of black mamba does reach 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) in Kenya and 1,650 metres (5,410 ft) in Zambia.[20] The black mamba was also recorded in 1954 in West Africa in the Dakar region of Senegal.[20] However, this observation, and a subsequent observation that identified a second specimen in the region in 1956, has not been confirmed and thus the snake's distribution there is inconclusive.[20] The black mamba's distribution contains gaps within the Central African Republic, Chad, Nigeria and Mali. These gaps may lead physicians to misidentify the black mamba and administer an ineffective antivenom.[20]

Habitat

The black mamba has adapted to a variety of climates ranging from savanna, woodlands, rocky slopes, dense forests and even humid swamps.[20] The grassland and savanna woodland/shrubs that extend through central, eastern and southern Africa are the black mamba's typical habitat.[20] The black mamba prefers more arid environments such as light woodland, rocky outcrops, and semi-arid dry bush country.[20]

Environmental encroachment

The black mamba's environment is rapidly diminishing. In Swaziland alone, 75% of the population is employed by subsistence farming.[21] Because of agricultural encroachment on the black mamba's habitat, the snake is commonly found in sugarcane fields. The black mamba will climb to the top of the sugarcane to bask in the sun and possibly wait for prey. The majority of human attacks occur in the sugarcane fields of east and southern Africa in which are employed thousands of workers for manual labour, as cane growing is not a highly mechanised industry. This encroachment on the snake's territory contributes to potentially dangerous human contact with these venomous snakes.[18]

Behaviour

The black mamba uses its speed to escape threats, not to hunt prey.[18] It is known to be capable of reaching speeds of around 20 kilometers per hour (12 mph), traveling with up to a third of its body raised off the ground.[18] Over long distances the black mamba can travel 11 to 19 kilometers per hour (6.8 to 11.8 mph), but in short bursts it can reach a speed of 16 to 20 kilometers per hour (9.9 to 12.4 mph), or even 23 kilometers per hour (14 mph) [22] making it the fastest land snake.[23] It is shy and secretive; it always seeks to escape when a confrontation occurs.[18] If a black mamba is cornered it mimics a cobra by spreading a neck-flap, exposing its black mouth, and hissing.[18] If this endeavor to scare away the attacker fails, the black mamba may strike repeatedly.[18] The black mamba is a diurnal snake. Although its scientific name seems to be indicative of tree climbing, the black mamba is rarely an arboreal snake.[23] These snakes retreat when threatened by predators.[22]

Hunting and prey

As stated, the black mamba is diurnal. It is an ambush predator that waits for prey to get close.[22] If the prey attempts to escape, the black mamba will follow up its initial bite with a series of strikes.[22] When hunting, the black mamba has been known to raise a large portion of its body off the ground.[22] The black mamba will release larger prey after biting it, but smaller prey, such as birds or rats, are held onto until the prey's muscles stop moving.[22] They have been known to prey on bushbabies, bats, and small chickens.[17]

Myths

It is the fastest moving snake in Africa, and one of the fastest moving snakes in the world, perhaps the fastest.[5][4][6][24] Many exaggerated stories of the black mamba's moving speed have been spread,[25] The elongated slender body creates the impression that the black mamba is moving faster than it really is.[26] thus creating myths like it outrunning a galloping horse or a running human. It is surely fast enough to catch a person walking but definitely can't catch a person running. On April 23 1906, on the Serengeti Plains, Kenya, an intentionally provoked and angry black mamba was recorded at a speed of 11 km/h (6.8 mph), over a distance of 43 m (141 ft).[27][28][29] A black mamba would not exceed 16 km/h (9.9 mph).[25][26] and it can only maintain such relatively high speeds for short distances.[26] Some have speculated that speeds of 16 to 19 km/h (9.9 to 11.8 mph) may be possible in short bursts over level ground.[30] Besides the relatively high speed with which it moves, the black mamba can strike accurately in any direction, even while moving fast. In striking, it throws its head upward from the ground for about two-fifths the lengths of its body.[31]

Predators

Not many predators challenge an adult black mamba, thus it enjoys a somewhat invulnerable status. However, it does face a few threats such as birds of prey particularly snake eagles (genus Circaetus). Although all commonly prey on snakes, there are two species in particular that do so with high frequency, including preying on black mambas. The two species are the Black-chested Snake Eagle (Circaetus pectoralis) and the Brown Snake Eagle (Circaetus cinereus). The Cape file snake (Mehelya capensis) which is apparently immune to all african snake venoms and prey on other snakes including venomous ones, is a common predator of black mambas (up to a size it can swallow).[32][17][33] Mongooses which are also partially immune to venom, and are quick enough to evade a bite, will readily tackle a black mamba for prey.[34] Humans do not usually consume black mambas, but they often kill them out of fear.

Venom

Based on the median lethal dose (LD50) values in mice, the black mamba LD50 from all published sources is as follows:

- (SC) subcutaneous (most applicable to real bites): 0.32 mg/kg,[9][35][36] 0.28 mg/kg.[7][15]

- (IV) intravenous: 0.25mg/kg,[9][35] 0.011mg/kg.[37]

- (IP) intraperitoneal: 0.30mg/kg (average),[38] 0.941 mg/kg.[9] 0.05mg/kg[39] (the last quote doesn't make it clear if is either intravenous or intraperitoneal).

Its bites can deliver about 100–120 mg of venom on average and the maximum dose recorded is 400 mg. It is reported that before the antivenom was widely available, the mortality rate from a bite could be nearly 100%.[18] Black mamba bites can potentially kill a human within 20 minutes, but death usually occurs after 30–60 minutes, sometimes taking up to three hours. (The fatality duration and rate depend on various factors, such as the health, size, age, psychological state of the human, the penetration of one or both fangs from the snake, amount of venom injected, location of the bite, and proximity to major blood vessels.[18] The health of the snake and the interval since it last used its venom mechanism is also important.) Presently, there is a polyvalent antivenom produced by SAIMR (South African Institute for Medical Research) to treat all black mamba bites from different localities.[11]

If bitten, common symptoms for which to watch are rapid onset of dizziness, coughing or difficulty breathing, and erratic heartbeat.[11] In extreme cases, when the victim has received a large amount of venom, death can result within an hour from respiratory or cardiac arrest.[11] Also, the black mamba's venom has been known to cause paralysis.[11] Death is due to suffocation resulting from paralysis of the respiratory muscles.[11]

The black mamba is regarded as one of the most dangerous and feared snakes in Africa due to various factors.[14] Nevertheless, attacks on humans by black mambas are rare, as the snakes usually avoid confrontation with humans and their occurrence in highly-populated areas is not very common compared with some other species.[40]

Toxin

The black mamba's venom is dendrotoxin. The toxin disrupts the exogenous process of muscle contraction by means of the sodium potassium pump. In an experiment,the death time of a mouse after subcutaneous injection of some toxins studied is around 7 minutes. However, a black mamba venom can kill a mouse after 4.5 minutes.[14]

Case reports

In a reported case in which a black mamba attacked and killed nine people at the same time is explained by biologist Joe Wasilewski in a short video clip. In an African village, screams were heard coming from someone in a hut. Another person heard the screams and entered the hut but never came out. This continued until a total of nine people entered the hut. Screams were heard but after the ninth person who entered the hut, nobody else was willing to see what was going on inside. The next day, some courageous locals gathered with spears and other weapons and entered the hut. As they walked into the hut, they witnessed nine dead people and a baby who was alive but hungry. The hut was a refuge which the mamba had decided to spend the night in, but as one person after the other walked into the hut, the snake felt cornered and became very defensive. It attacked each and everyone of the people that entered the hut. Because of the disturbingly rapid death times of the nine victims, the attacks must have been extraordinarily savage in nature.[41]

A survey of snakebites in South Africa from 1957 to 1963 recorded over 900 venomous snakebites, but only seven of these were confirmed black mamba bites. From the 900 bites, only 21 ended in fatalities, including all seven black mamba bites – a 100% mortality rate.[42]

Danie Pienaar, head of South African National Parks Scientific Services, garnered much media attention due to the fact that he had survived the bite of a black mamba without antivenom. Mortality rates among those not receiving any kind of adequate medical attention (antivenom, mechanical ventilation, intubation, drug therapy, etc) is 100%. This is why the case of Danie Pienaar stands out and why it garnered such media attention internationally. However, although no antivenom was administered, Pienaar was in serious condition despite the the fact the hospital physicians declared it a "moderate" black mamba envenomation. At one point, he lapsed into a coma and his prognosis was declared "poor". Still, upon arrival at the hospital Pienaar was immediately intubated, given supportive drug therapy, put on mechanical ventilation and was placed on life support for three days until the toxins were flushed out of his system, and released from the hospital on the fifth day. He miraculously survived the bite and made a full recovery. Danie believes he survived for a number of reasons. “Firstly, it was not my time to go.” The fact that he stayed calmed and moved slowly definitely helped. The tourniquet was also essential. “It was not easy to stay calm,” he says. “It was almost as if I dislodged myself from my body and was talking to someone else the entire time.” “I also knew snakes and have never been scared of them,” he said. The experience has not left Danie with antagonism towards the black mamba. “Snakes do not eat people. I was on my way and cut the snake off from where it wanted to go.”[43][44] He was featured on I'm Alive (TV series) (SE1EP8).

In 2006 a case of an elephant dying of a black mamba snakebite was reported in the October 2006 issue of the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Up until then there were only published cases of elephants being killed by king cobras bites.[45] On 10 October 2003, sometime between 1:00 pm and 3:00 pm local time, a full grown female African elephant named Eleanor that weighed around 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) at Samburu National Reserve in Kenya was bitten by a black mamba. The effects of the venom were rapid; a short time later Eleanor began to slow down, showed an unsteady gait and began to fall behind the rest of the herd, which was highly unusual behaviour for a matriarch, who is always ahead of the herd and leading the way. Not long after, Eleanor fell to the ground and was helped up by another elephant until she fell again and never got up. The bite was fatal to the matriarch, who suffered for a lengthy period of time (just under 24 hours) from the effects of the venom before finally dying. The dramatic images show one elephant, Grace, who was a matriarch of a different herd, struggling to help the 40-year-old matriarch Eleanor, who lay on the ground, languishing in agony and struggling to breath as a result of the black mamba bite. The footage shot by scientists, show Grace calling out in distress and making desperate attempts to get the dying elephant back onto her feet. The next day, 11 October 2003 at around 11:00 am local time, Eleanor's lifeless body was visited by other elephants, who rocked back and forth in mourning or stood silently, paying their last respects. In all, five distinct herds or families of elephants visited the dead body of Eleanor to pay respect. This female elephant, Eleanor, was a herd matriarch and it had been being observed by a research team of scientists led by Dr. Iain Douglas-Hamilton from Oxford University's Department of Zoology, and the founder of the Save the Elephants charity and the University of California for many years. The team of scientists and the public focused their attention on the behaviours and emotions that were displayed by elephants of different families towards the dying matriarch and not at the fact that the elephant died of a mamba snakebite.[46][47][48][49][50]

In 2013, in a very rare and unusual case, American professional photographer, Mark Laita, was bitten on his leg by a black mamba during a photo-shoot of a black mamba at a facility in Central America. Both the snake fangs hit an artery in his calf, and he was gushing blood profusely. Laita did not go to the doctor or the hospital, and except for the swollen fang marks giving him intense pain during the night, he was not affected and was fine physically. This led him to believe that the snake either gave him a 'dry bite' (meaning without injecting venom) or that the heavy bleeding pushed the venom out. Some commenters to the story suggested that it was a venomoid snake (in which the venom glands are surgically removed). Laita responded that it was not the case. Only in retrospective, Laita found out that he captured the snake biting his leg on film.(see citation for the photo)[50][51][52]

Gallery

-

Black mamba at Wilmington's Serpentarium

-

Close-up of a black mamba's head

-

A black mamba at the St Louis zoo

References

- ^ "Dendroaspis polylepis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Uetz, P. "Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864". Reptile Database. Zoological Museum Hamburg. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ a b Van Der Vlies, C. (2010). Southern Africa Wildlife and Adventure. British Columbia, Canada/Indiana, United States: Trafford Publishing. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-1-4269-1932-9.

- ^ a b Austin Stevens: Snakemaster, (2002) "Seven Deadly Strikes" documentary

- ^ a b World Book, Inc (1999) The World Book encyclopedia, Volume 1, Page 525

- ^ a b Spawls, S.; Branch, B. (1995). The dangerous snakes of Africa: natural history, species directory, venoms, and snakebite. Dubai: Oriental Press: Ralph Curtis-Books. pp. 49–51. ISBN 0-88359-029-8.

- ^ Minton, Minton, SA, MR (1969). Venomous Reptiles. USA: New York Charles Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Fry, Bryan, Deputy Director, Australian Venom Research Unit, University of Melbourne (March 9, 2002). "Snakes Venom LD50 – list of the available data and sorted by route of injection". venomdoc.com. (archived) Retrieved October 14, 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Fry, Bryan" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Visser, Chapman, J, DS (1978). Snakes and Snakebite: Venomous snakes and management of snake bite in Southern Africa. Purnell. ISBN 0-86843-011-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Immediate first aid for bites by Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis)". Toxicology. University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 3 December 2013. Cite error: The named reference "Davidson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lee, Douglas (November–December 1996). "Black Mamba! Meet the African Species That One Expert Calls 'Death Incarnate'". International Wildlife. 26 (6): 48. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ Black mamba: Kiss of death, Smithsonian Networks

- ^ a b c Strydom, Daniel (1971-11-12). "Snake Venom Toxins" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ a b JERRY G. WALLS, The World's Deadliest Snakes, Reptiles (magazine)

- ^ Wasilewski, Joe (2011). Wildlife Footage (Motion picture). Africa: Youtube. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Haagner, GV; Morgan, DR (January 1993). "The maintenance and propagation of the Black mamba Dendroaspis polylepis at the Manyeleti Reptile Centre, Eastern Transvaal". International Zoo Yearbook. 32 (1): 191–196. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1993.tb03534.x. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Black mamba". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ a b c Mattison, Chris (1987-01-01). Snakes of the World. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Håkansson, Thomas (1983-01-01). "On the Distribution of the Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in West Africa". Journal of Herpetology. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. JSTOR 1563464.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "UNDP: Human development indices – Table 3: Human and income poverty (Population living below national poverty line (2000-2007))" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 28 November 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Richardson, Adele (2004). Mambas. Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press. p. 25. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ^ a b Maina, J.N (1989-12). "The morphology of the lung of the black mamba Dendroaspis polylepis". The Journal of Anatomy. PMC 1256818.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Irwin, Steve (July 30, 2000) "Africa's Deadliest Snakes" , The Crocodile Hunter (SE3EP27)

- ^ a b MIKAEL JOLKKONEN, Muscarinic Toxins from Dendroaspis (Mamba) Venom Page 15, Uppsala University

- ^ a b c Warren, Schmidt (2006) Reptiles & Amphibians of Southern Africa, Page 34

- ^ Gerald L. Wood , (1976) The Guinness book of animal facts and feats, Page 132

- ^ Leopard, Marten (2002) International Wildlife Encyclopedia, Page 1530

- ^ Harry W. Greene, (1997), Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature, Page 40

- ^ Medd Guinness (1993), The Guinness Book of Records, Page 35

- ^ Burton, R. (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia: Leopard – marten. USA: Marshall Cavendish. p. 3168. ISBN 0-7614-7277-0.

- ^ Bauchot, R. (2006). Snakes: A Natural History. Sterling. pp. 41, 76, 176. ISBN 978-1-4027-3181-5.

- ^ Mehelya capensis (Southern file snake, Cape file snake), Iziko South African Museum

- ^ Caught in the Act: Mongoose Vs. Snake (Video), "A mongoose takes on the most infamous snake of all, the black mamba.", National Geographic

- ^ a b Sherman A. Minton, (May 1, 1974) Venom diseases, Page 116

- ^ Philip Wexler, 2005, Encyclopedia of toxicology, Page 59

- ^ Thomas J. Haley, William O. Berndt, 2002, Toxicology, Page 446

- ^ Scott A Weinstein, David A. Warrell, Julian White and Daniel E Keyler (Jul 1, 2011) ” Bites from Non-Venomous Snakes: A Critical Analysis of Risk and Management of "Colubrid” Snake Bites (page 246)

- ^ Zug, GR. (1996). Snakes in Question: The Smithsonian Answer Book. Washington D.C., USA: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. ISBN 1-56098-648-4.

- ^ The new encyclopedia of Reptiles (Serpent). Time Book Ltd. 2002.

- ^ Wasilewski, Joe (2011). Wildlife Footage (Documentary). Africa: Youtube. Event occurs at 0m55s. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ O'Shea, M. (2005). Venomous Snakes of the World. United Kingdom: New Holland Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 0-691-12436-1.

... in common with other snakes they prefer to avoid contact; ... from 1957 to 1963 ... including all seven black mamba bites - a 100 per cent fatality rate

- ^ "Scientists gather in Kruger National Park for Savanna Science Network Meeting". South African Tourism. 5 March 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Surviving a Black Mamba bite". Siyabona Africa - Kruger National Park. Siyabona Africa. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ Dr Debra Bourne MA VetMB PhD MRCVS, Snake Bite in Elephants and Ferrets, Twycross Zoo

- ^ Douglas-Hamilton, I.; Bhalla, Shivani; Wittemyer, George; Vollrath, Fritz (October 2006). "Behavioural reactions of elephants towards a dying and deceased matriarch". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 100 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.04.014.

- ^ Brennen, Zoe. "Elephants with broken hearts". Daily Mail. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Dying Elephant Elicits Compassion". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Scientists see depth of elephant feelings". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ a b Rowan Hooper (January 19,2012) Portraits of snake charm worth elephant-killing bite newscientist

- ^ http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/snakes-in-a-frame-mark-laitas-stunning-photographs-of-slithering-beasts-27577991/?no-ist

- ^ http://strangebehaviors.wordpress.com/2013/02/24/black-mamba-bite-the-back-story/

Further reading

- Thorpe, Roger S.; Wolfgang Wüster, Anita Malhotra (1996). Venomous Snakes: Ecology, Evolution, and Snakebite. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854986-4

- McDiarmid, Roy W.; Jonathan A. Campbell; T'Shaka A. Tourè (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologists' League. ISBN 978-1-893777-01-9

- Spawls, Stephen; Branch, Bill (1995). Dangerous Snakes of Africa: Natural History - Species Directory - Venoms and Snakebite.Ralph Curtis Pub; Revised edition. ISBN 978-0-88359-029-4

- Dobiey, Maik; Vogel, Gernot (2007). Terralog: Venomous Snakes of Africa (Terralog Vol. 15). Aqualog Verlag GmbH.; 1 edition. ISBN 978-3-939759-04-1

- Mackessy, Stephen P. (2009). Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles. CRC Press; 1 edition. ISBN 978-0-8493-9165-1

- Greene, Harry W.; Fogden, Michael; Fogden, Patricia (2000). Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22487-2

- Spawls, Stephen; Ashe, James; Howell, Kim; Drewes, Robert C. (2001). Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa: All the Reptiles of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-12-656470-9

- Broadley, D.G.; Doria, C.T.; Wigge, J. (2003). Snakes of Zambia: An Atlas and Field Guide. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Edition Chimaira. ISBN 978-3-930612-42-0

- Marais, Johan (2005). A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Nature. ISBN 978-1-86872-932-6

- Engelmann, Wolf-Eberhard (1981). Snakes: Biology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Leipzig; English version NY, USA: Leipzig Publishing; English version published by Exeter Books (1982). ISBN 0-89673-110-3

- Minton, Sherman A. (1969). Venomous Reptiles. USA: New York Simon Schuster Trade. ISBN 978-0-684-71845-3

- FitzSimons, Vivian FM (1970). A field guide to the snakes of Southern Africa. Canada: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-212146-8

- Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (2013). Venomous Snakes of the World: A Manual for Use by U.S. Amphibious Forces. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62087-623-7

- Branch, Bill (1988). Bill Branch's Field Guide to the Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa (More than 500 Photographs for Easy Identification). Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86977-641-4

- Branch, Bill (1998). Field Guide to the Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Ralph Curtis Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88359-042-3

- Branch, Bill (2005). Photographic Guide to Snakes Other Reptiles and Amphibians of East Africa. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. ISBN 978-0-88359-059-1

- Mara, Wil; Collins, Joseph T; Minton, SA (1993). Venomous Snakes of the World. TFH Publications Inc. ISBN 978-0-86622-522-9

- Stocker, Kurt F. (1990). Medical Use of Snake Venom Proteins. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-5846-3

- Mebs, Dietrich (2002). Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Medpharm. ISBN 978-0-8493-1264-9

- White, Julian; Meier, Jurg (1995). Handbook of Clinical Toxicology of Animal Venoms and Poisons. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4489-3

- Vitt, Laurie J; Caldwell, Janalee P. (2013). Herpetology, Fourth Edition: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-386919-7

- Tu, Anthony T. (1991). Handbook of Natural Toxins, Vol. 5: Reptile Venoms and Toxins. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8376-1

- Mattison, Chris (1995). The Encyclopedia of Snakes. Facts on File; 1st U.S. Edition edition. ISBN 978-0-8160-3072-9

- Coborn, John (1991). The Atlas of Snakes of the World. TFH Publications. ISBN 978-0-86622-749-0

External links

![]() Media related to Dendroaspis polylepis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dendroaspis polylepis at Wikimedia Commons

- Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864

- Black Mamba - Clinical Toxinology Resource

- National Geographic

- Dendroaspis polylepis at the Reptile Database

- Blue Planet Biomes

- The Animal Files - Black mamba

- PBS - Nature - Black mamba introduction

- Video of the black mamba (02m00s-09m08s) on YouTube

- Video of the black mamba on YouTube

- Full length black mamba documentary - Austin Stevens Snakemaster - In Search of the Black Mamba on YouTube