Body Parts (film)

| Body Parts | |

|---|---|

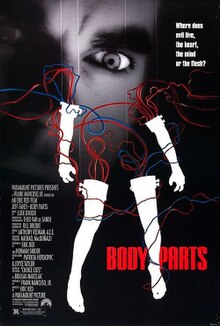

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Eric Red |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Choice Cuts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac |

| Produced by | Frank Mancuso Jr. |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Theo van de Sande |

| Music by | Loek Dikker |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1] |

| Box office | $9.2 million[2] |

Body Parts is a 1991 American body sci-fi horror film directed by Eric Red and starring Jeff Fahey, Kim Delaney, Brad Dourif, Zakes Mokae, and Lindsay Duncan. It was produced by Frank Mancuso Jr., from a screenplay by Red and Norman Snider, who dramatized a story that Patricia Herskovic and Joyce Taylor had based on the horror novel Choice Cuts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. The film follows a psychologist who undergoes an experimental arm transplant surgery and begins having visions of murders.

Plot

Bill Chrushank is a psychologist working with convicted killers at a prison. While driving to work, Bill gets in a horrific car accident and loses an arm. At the hospital, Dr. Agatha Webb convinces Bill's wife to sign off on an experimental transplant surgery.

Bill awakens from the surgery and begins to adjust to his new arm. After he is released from the hospital, he resumes his work and things seem to be back to normal. However, Bill starts seeing visions of horrible acts of murder (as if he is committing them) and occasionally loses control of his new arm. At the prison, a convict tells Bill that the tattoo on his new arm is only given to inmates on death row. Bill has a police friend scan his new fingerprints and is shocked to discover the arm came from convicted serial killer Charley Fletcher, who had murdered 20 people.

Bill confronts Dr. Webb and finds the identities of two other patients: Mark Draper and Remo Lacey who received the killer's legs and other arm, respectively. Bill visits Remo, who was a struggling artist before the transplant but now is making a small fortune selling paintings he made with his new arm. Noting Remo's paintings depict the same visions he had, Bill tells him that he is painting what the killer saw. Remo, however, only cares about his newfound success and dismisses Bill's warnings. Bill meets Mark and tries to warn him but Mark is just happy to be able to walk again and advises Bill to be grateful and move on.

Bill becomes increasingly agitated and violent. He demands that Dr. Webb remove his arm but she refuses, stating that the problems he is experiencing are insignificant compared to her experiment's success. Bill meets up with Remo and Mark at a bar. A drunk man recognizes Bill from news about the surgery, and demands to see his arm. Bill snaps and a bar fight breaks out where Bill single-handedly takes out several men and almost kills one before being stopped.

As Mark returns home, his legs suddenly stop functioning. Scared, Mark calls Bill, who hears Mark yell and struggle with someone. Bill goes to Mark's apartment and finds him dead, with both legs missing. Bill calls the police and implores the lead detective to check on Remo. However, they are too late as Charley — who is still alive, having his head transplanted onto a new body — rips Remo's arm off and throws him out a window.

As Bill and the detective stop at a traffic light, Charley pulls up in a car beside them and handcuffs his wrist to Bill's. Charley speeds away, and the detective desperately tries to keep up, lest Bill's arm gets ripped off. Bill uses the detective's gun to destroy the handcuff just before they hit a divider that splits the road in two. As the detective leaves the car and opens fire on Charley, Bill drives away to pursue the killer. Charley brings his old limbs back to Dr. Webb.

Armed with a gun from the detective's car, Bill enters the hospital and finds Charley's torso and limbs in a glass case, wiggling as if having a mind of their own. Dr. Webb appears and says she is ready to take the arm back, and Charley knocks Bill unconscious. Bill wakes up strapped to an operating table. As Dr. Webb approaches him with a circular saw, he breaks his restraints, knocks her out and wrestles with Charley for his shotgun. Right before Charley can pull the trigger, Bill is able to snap his neck. He destroys the glass case and shoots at Charley's body parts. Charley, still alive, aims at Bill with the detective's gun, but accidentally kills Dr. Webb. Bill shoots Charley in the head, killing him for good.

Bill sits with his wife in a park. In his journal, he notes that he hasn't had any other problems with the arm after Charley's death, and he is still thankful to both Dr. Webb and Charley for the new arm.

Cast

- Jeff Fahey as Bill Chrushank

- Brad Dourif as Remo Lacey

- Kim Delaney as Karen Chrushank

- Zakes Mokae as Detective Sawchuck

- Lindsay Duncan as Dr. Agatha Webb

- Paul Ben-Victor as Ray Kolberg

- Peter Murnik as Mark Draper

- John Walsh as Charley Fletcher

- Nathaniel Moreau as Bill Jr.

- Peter MacNeill as Drunk

- Arlene Duncan as Nurse

- Lindsay G. Merrithew as Roger

- Andy Humphrey as Ricky

- Sarah Campbell as Samantha

- James Kidnie as Detective Jackson

Production

Principal photography of Body Parts was scheduled to begin on December 10, 1990 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, but was postponed until January 1991.[3] Filming completed in late February.[3] Despite this, director Eric Red recalls filming in late 1989 and early 1990 in the commentary to the 2020 Blu-ray release.

The score by Dutch composer Loek Dikker is notable for its prominent use of a singing saw.

Release

Body Parts was theatrically released August 2, 1991 in 1,300 theaters.[3] Paramount pulled ads for the film in Milwaukee, Wisconsin after police found dismembered bodies in Jeffrey Dahmer's apartment.[4]

Critical response

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 38% based on 16 critics, with an average rating of 4.47/10.[5] Variety wrote, "What could have been a reasonably interesting thriller literally goes to pieces in last third, until the brain seems the most salient part missing."[6] Janet Maslin of The New York Times called it "an intriguing sleeper" that "makes the mistake of opting for grisly horror effects when a less literal-minded approach would be more compelling."[7] Stephen Wigler of The Baltimore Sun called it a distasteful, "so-bad-it's-almost-good film" that is "the best film for barbecue lovers since The Texas Chainsaw Massacre."[8] Peter Rainer of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "isn't quite as terrible as you might imagine."[9] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post wrote that the film has an interesting premise but does not live up to it.[10] Time Out London called it a "tacky but vigorous mad doctor movie".[11] Patrick Naugle of DVD Verdict criticized the pacing and screenplay.[12]

Home media

It was first released on home video February 20, 1992[13] and later on DVD September 14, 2004.[14] Scream Factory released the film for the first time on Blu-ray on January 28, 2020.[15]

See also

References

- ^ Harris, Blake (March 24, 2017). "How Did This Movie Get Made: A Conversation with Eric Red, Director of 'Body Parts'". /Film. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020.

- ^ "Body Parts". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Body Parts". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020.

- ^ Fox, David J. (July 26, 1991). "Paramount Pulls 'Body Parts' Ads". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Body Parts". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Review: 'Body Parts'". Variety. December 31, 1990. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (August 3, 1991). "Body Parts (1991)". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Wigler, Stephen (August 3, 1991). "'Body Parts' doesn't quite make a whole". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Rainer, Peter (August 5, 1991). "Movie Review : 'Body Parts' Fails Its Premise". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (August 5, 1991). "'Body Parts'". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Body Parts". Time Out London. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Naugle, Patrick (November 5, 2004). "Body Parts". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on November 9, 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. (February 20, 1992). "Home Video". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (September 14, 2004). "Violence From Denzel Washington; Talking Cows From Disney". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Body Parts – Blu-ray". Scream Factory. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020.

External links

- 1991 films

- 1991 horror films

- 1990s slasher films

- English-language films

- American films

- American serial killer films

- American slasher films

- American body horror films

- Films based on French novels

- Films based on works by Boileau-Narcejac

- Films directed by Eric Red

- Films scored by Loek Dikker

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films shot in Toronto

- Films about organ transplantation

- Paramount Pictures films