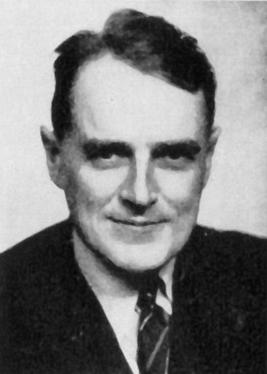

Bruce Marshall (writer)

Bruce Marshall | |

|---|---|

Dustjacket photo from Vespers in Vienna (1947) | |

| Occupation | Novelist & Accountant |

Lieutenant-Colonel Claude Cunningham Bruce Marshall, known as Bruce Marshall (24 June 1899 – 18 June 1987) was a prolific Scots writer who wrote fiction and non-fiction books on a wide range of topics and genres. His first book, A Thief in the Night came out in 1918, possibly self-published. His last, An Account of Capers was published posthumously in 1988, a span of 70 years.

Life & Work

Marshall was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, the son of Claude Niven Marshall and Annie Margaret (Bruce) Marshall. He was educated at St. Andrews. He became a Roman Catholic in 1917 and remained active and interested in the faith for the rest of his life. He was a member and at times served as an officer in the Una Voce and the Latin Mass Society organizations.

During World War I he initially served as a private in the Highland Light Infantry. He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant into the Royal Irish Fusiliers in 1918. Six days before the 1918 Armistice he was seriously wounded. Courageous German medical orderlies risked intense shelling to rescue him and he was taken prisoner.[1] His injuries resulted in the amputation of one leg. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant in 1919 and invalided out in 1920.

After the war he completed his education in Scotland, became an auditor, and moved to France where he worked in the Paris branch of Peat Marwick Mitchell.[2]

In 1928 he married Mary Pearson Clark (1908-1987).[3] They had one daughter—Sheila Elizabeth Bruce Marshall. In 2009, his granddaughter, Leslie Ferrar, was Treasurer to the Prince of Wales.

He was living in Paris during the 1940 Invasion of France and escaped only two days before the Nazi occupied the city. Returning to England he rejoined the military, initially serving in the Royal Army Pay Corps as a Lieutenant. He was promoted to Captain in Intelligence, assisting the French underground, and then was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Displaced Persons Division in Austria.[4] He transferred to the General List in 1945, and left the Army as a Lieutenant-Colonel in 1946.

After the war Marshall returned to France,[3] moving to the Côte d'Azur and living there for the remainder of his life. He died in Biot, France, six days before his 88th birthday.

Writing career

A Roman Catholic convert[5], his stories are usually humorous and mildly satiric and typically have religious overtones. Important themes which run through his works are Catholicism, accounting, a Scottish heritage and war, adventure and intrigue. Often major characters are Catholic priests or accountants. Characters in his novels are often fond of animals and concerned about their treatment. Contempt for modern art and literature is often expressed.

Marshall's first literary work was a collection of short stories entitled A Thief in the Night published while he was still a student at St. Andrews University.[6] His first novel, This Sorry Scheme was published in 1924. A stream of novels soon followed, but none of the fiction he wrote before the Second World War gained as much notoriety or staying power as Father Malachy's Miracle (1931).

It was not until after the Second World War that Marshall was able to become a writer full-time, giving up his work as an accountant."

As to his dual career as an accountant and writer, Marshall once said, "I am an accountant who writes books. In accounting circles I am hailed as a great writer. Among novelists I am assumed to be a competent accountant."[7]

Among his better known works after the Second World War is The White Rabbit (1953), a biography of Wing Commander F. F. E. Yeo-Thomas, describing in vivid detail his exploits and sufferings while in the Resistance during World War II.

In 1959 he was awarded the Włodzimierz Pietrzak prize.

The theme of much of Marshall's works is religion, with a focus on Roman Catholicism. His first great success, Father Malachy's Miracle, is about an innocent Scottish priest whose encounter with sinful behavior causes him to become involved in a miracle. A number of his later novels also deal with clergy who are faced with temptation but manage to triumph in a modest and humble manner (e.g., The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith (AKA All Glorious Within) (1944), A Thread of Scarlet (AKA Satan and Cardinal Campbell) (1959), Father Hilary's Holiday (1965), The Month of the Falling Leaves (1963)). Other books centered on religious issues deal more with Catholic doctrine and its relationship to modern life than with personal responsibility, such as The Bishop (1970), Peter the Second (1976), Urban the Ninth (1973) and Marx the First (1975).

Like many expatriates, Marshall expressed great love for his homeland. Most of his books were either set in Great Britain and/or have main characters of British nationality. The work which best shows Marshall's affection for Scotland may be The Black Oxen (1972), which Marshall billed as a Scottish Epic.

Several of Marshall's books have themes about espionage and intrigue, such as Luckypenny (1937), A Girl from Lübeck (1962), The Month of the Falling Leaves (1963), Operation Iscariot (1974), An Account of Capers (1988), The Accounting (AKA The Bank Audit) (1958), and Only Fade Away (1954).

Some of his novels feature major characters who, like Marshall himself, have suffered the loss of a limb. Often major characters from one novel will appear in minor roles in other novels.

Marshall was relatively popular in his time. At least two of his books were Book of the Month Club selections;[4] Vespers in Vienna (1947) and The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith (AKA All Glorious Within) (1944), in June 1945. An Armed Services Edition of The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith was also produced.

His books were published in at least nine languages — English, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Polish, Czech, Portuguese & Spanish.

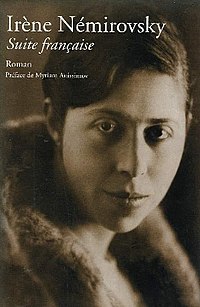

Yellow Tapers for Paris & Suite Française

Some readers have noticed similarities between Marshall's 1943 novel Yellow Tapers for Paris and Irène Némirovsky's Suite Française which was written at about the same time, but not discovered until 1998.

There is no suggestion of plagiarism -- Némirovsky had been murdered before Marshall's novel was published and no one saw Némirovsky's work before its 1998 discovery.

The stories cover the leadup to the Nazi Invasion and its immediate aftermath, but the events of the respective stories are much different. Marshall's ends before the occupation, while Némirovsky's has significant portions devoted to it. Both works have major characters who work in the financial field—Marshall's protagonist is a financial accountant while Némirovsky's work has major characters who work for a bank.

Both books were written during and/or immediately after the actual period itself, but show considerable reflection—they aren't just "diary" entries. Even more remarkable considering the activities of the authors at the time—Némirovsky struggling to evade the Nazis and protect her two daughters and Marshall working for the British Army.

There are also remarkable parallels in the two writers' lives.

They were close in age, Marshall was born in 1899 and Némirovsky in 1903.

Both were converts to Catholicism.

Both authors were parents of similar aged daughters—the birthdate of Marshall's daughter, Sheila, is not available, but her husband was born in 1927. One would assume that she was close to the same age as Némirovsky's oldest daughter, Denise, who was born in 1929.

Both writers were expatriates living in Paris at the same time (sometime in the early 1920s until the Nazi invasion). Both were successful writers, and lived in a place, Paris, during a time when writers were greatly celebrated -- "The Lost Generation." It's not hard to imagine that one or both of them could have crossed paths with some of the literary notables living there during that period (Henry Miller, Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford, Lytton Strachey, Edith Sitwell, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Edith Wharton, Gertrude Stein, etc.). However, there is no evidence that Némirovsky and Marshall ever met.

Marshall worked for a financial accounting firm while Némirovsky's family was in banking.

Both were well-established and prolific novelists at the time of the invasion—Némirovsky's first novel was published in 1927, and she had published about 14 novels by 1940. Marshall's first was in 1924 and he had published about 15 novels by 1940.

Both fled the Nazi invasion and wrote novels partly based on those experiences.

Movie, Stage & TV Adaptions

His 1931 novel Father Malachy's Miracle was adapted for the stage in 1938 by Brian Doherty.[8] The novel was adapted for presentation on The Ford Theatre Hour, an American TV show, in 1950. In 1961 the novel was the basis for the German film Das Wunder des Malachias directed by Bernhard Wicki and starring Horst Bollmann, Richard Münch and Christiane Nielsen.

His 1947 novel Vespers in Vienna was the basis of the 1949 film The Red Danube starring Walter Pidgeon, Ethel Barrymore, Peter Lawford, Angela Lansbury and Janet Leigh. George Sidney directed. After the movie's release the novel was re-issued under the title The Red Danube.

His 1953 novel The Fair Bride was the basis of the 1960 film The Angel Wore Red starring Ava Gardner, Dirk Bogarde, Joseph Cotten and Vittorio De Sica. It was the last film directed by Nunnally Johnson.

His 1952 book, The White Rabbit, recounting the World War II exploits of secret agent F. F. E. Yeo-Thomas, was made into a TV mini-series in 1967.

His 1963 novel The Month of the Falling Leaves was the basis of the 1968 German TV show Der Monat der Fallenden Blätter. Marshall co-wrote the screenplay with Herbert Asmodi. It was directed by Dietrich Haugk.

Bibliography

- A Thief in the Night (ca 1918)

- This Sorry Scheme (1924)

- The Stooping Venus; a Novel (1926)

- Teacup Terrace (1926)

- And There Were Giants ... (1927)

- The Other Mary (1927)

- High Brows, an Extravaganza of Manners—Mostly Bad ... (1929)

- The Little Friend (1929)

- The Rough House, a possibility (1930)

- Children of This Earth (1930)

- Father Malachy's Miracle (1931)

- Prayer for the Living (1934)

- The Uncertain Glory (1935)

- Canon to the Right of Them (1936)

- Luckypenny (1937)

- Delilah Upside Down, a Tract, with a Thrill (1941)

- Yellow Tapers for Paris, a Dirge (1943)

- The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith (AKA All Glorious Within) (1944)

- George Brown's Schooldays (1946)

- Vespers in Vienna (AKA The Red Danube) (1947)

- To Every Man a Penny (1949)

- Contribution to A Time to Laugh: A Risible Reader by Catholic Writers, edited by Paul J. Phelan (1949)

- "The Curé of Ars,"[9] chapter in Saints for Now, edited by Clare Boothe Luce (1952)

- Introduction to Rue Notre Dame, by Daniel Pezeril (1953)

- The Fair Bride (1953)

- The White Rabbit (1953) (biography)

- Thoughts of My Cats (1954) (semi-autobiography)

- Only Fade Away (1954)

- Foreword to Top Secret Mission, by Madelaine Duke (1955)

- Girl in May (1956)

- The Accounting (AKA The Bank Audit) (1958)

- A Thread of Scarlet (AKA Satan and Cardinal Campbell) (1959)

- The Divided Lady (1960)

- A Girl from Lübeck (1962)

- The Month of the Falling Leaves (1963)

- Father Hilary's Holiday (1965)

- The Bishop (1970)

- The Black Oxen (1972)

- Urban the Ninth (1973)

- Operation Iscariot (1974)

- Marx the First (1975)

- Peter the Second (1976)

- The Yellow Streak (1977)

- Prayer for a Concubine (1978)

- Flutter in the Dovecote (1986)

- A Foot in the Grave (1987)

- An Account of Capers (1988)

Notes

- ^ Marshall, B: The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith endnote. Houghton Mifflin 1945.

- ^ Purvis, John. "Claude Cunningham Bruce (Bruce) Marshall". The Purvis Family Tree. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ a b Herbert, Michael (2004). ‘Marshall, (Claude Cunningham) Bruce (1899–1987)’. Vol. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Marshall, B: The Accounting endnote Houghton Mifflin Company 1958.

- ^ Banfi, Alessandro. "The Man of the Eleventh Hour". Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ Marshall, B: A Thread of Scarlet endnote. Collins 1959.

- ^ Marshall, B: To Every Man a Penny endnote. Houghton Mifflin 1949.

- ^ "New Plays in Manhattan". Time magazine. November 29, 1937. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Father Malachy's Miracle play review - ^ Bruce Marshall: "The Curé of Ars"

References

- Contemporary Authors, Vols. 5-8, p. 733 (First Revision, 1969)

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 36, pp. 835-836 (2000)

External links

- 1899 births

- 1987 deaths

- British Army General List officers

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British Army personnel of World War II

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Highland Light Infantry soldiers

- People from Edinburgh

- Roman Catholic writers

- Royal Army Pay Corps officers

- Royal Irish Fusiliers officers

- Scottish novelists

- Scottish Roman Catholics