Camphor

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,7,7-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-one

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

1,7,7-Trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-one | |||

| Other names

2-Bornanone; Bornan-2-one; 2-Camphanone; Formosa

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3DMet | |||

| 1907611 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.860 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 83275 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Camphor | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2717 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H16O | |||

| Molar mass | 152.237 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White, translucent crystals | ||

| Density | 0.990 g cm−3 | ||

| Boiling point | 204 °C (399 °F; 477 K) | ||

| 1.2 g dm−3 | |||

| Solubility in acetone | ~2500 g dm−3 | ||

| Solubility in acetic acid | ~2000 g dm−3 | ||

| Solubility in diethyl ether | ~2000 g dm−3 | ||

| Solubility in chloroform | ~1000 g dm−3 | ||

| Solubility in ethanol | ~1000 g dm−3 | ||

| log P | 2.089 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 4 mmHg (at 70 °C) | ||

Chiral rotation ([α]D)

|

+44.1° | ||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 64 °C | ||

| Explosive limits | 3.5% | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Camphor (pronounced /ˈkæmfə/) is a waxy, white or transparent solid with a strong, aromatic odor.[3] It is a terpenoid with the chemical formula C10H16O. It is found in wood of the camphor laurel (Cinnamomum camphora), a large evergreen tree found in Asia (particularly in Sumatra, Borneo and Taiwan) and also of Dryobalanops aromatica, a giant of the Bornean forests. It also occurs in some other related trees in the laurel family, notably Ocotea usambarensis. Dried rosemary leaves (Rosmarinus officinalis), in the mint family, contain up to 20% camphor. It can also be synthetically produced from oil of turpentine. It is used for its scent, as an ingredient in cooking (mainly in India), as an embalming fluid, for medicinal purposes, and in religious ceremonies. A major source of camphor in Asia is camphor basil.

Norcamphor is a camphor derivative with the three methyl groups replaced by hydrogen.

History

The word camphor derives from the French word [camphre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), itself from Medieval Latin [camfora] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), from Arabic [kafur] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), from Sanskrit, karpūra.[4] The term ultimately was derived from Old Malay kapur barus which means "the chalk of Barus". Barus was the name of an ancient port located near modern Sibolga city on the western coast of Sumatra island (today North Sumatra Province, Indonesia). This port was initially built prior to the Indian - Batak trade in camphor and spices. Traders from India, East Asia and the Middle East would use the term kapur barus to buy the dried extracted ooze of camphor trees from local Batak tribesmen; in proto Malay-Austronesian language (Sanskrit adapted-Bataknese alphabets)] it is also known as [kapur Barus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Even now, the local tribespeople and Indonesians in general refer to naphthalene balls and moth balls as [kapur Barus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). For the local tribespeople, the use of camphor ranges from deodorant, wood-finishing veneer, traditional rituals and non-edible preservatives as the camphor tree itself is natively found in that region. The tree, called "Kamfer" in Indonesian, is also known for its resistance to tropical termites.[citation needed]

The sublimating capability of camphor is quite similar to alcohol, and an early international trade in it made camphor widely known throughout Arabia in pre-Islamic times, as it is mentioned in the Quran 76:5 as a flavoring for drinks. In the 9th century, the Arab chemist, Al-Kindi (known as Alkindus in Europe), provided the earliest "publicity" for the production of camphor in his Kitab Kimiya' al-'Itr (Book of the Chemistry of Perfume).[citation needed] By the 13th century, it was used in recipes everywhere in the Muslim world, ranging from main dishes such as tharid and stew to desserts.[5]

Already in the 19th century, it was known that with nitric acid, camphor could be oxidized into camphoric acid. Haller and Blanc published a semisynthesis of camphor from camphoric acid, which, although demonstrating its structure, would not prove it. The first complete total synthesis for camphoric acid was published by Gustaf Komppa in 1903. Its starting materials were diethyl oxalate and 3,3-dimethylpentanoic acid, which reacted by Claisen condensation to give diketocamphoric acid. Methylation with methyl iodide and a complicated reduction procedure produced camphoric acid. William Perkin published another synthesis a short time later. Previously, some organic compounds (such as urea) had been synthesized in the laboratory as a proof of concept, but camphor was a scarce natural product with a worldwide demand. Komppa realized this and began industrial production of camphor in Tainionkoski, Finland, in 1907.

Production

Camphor can be produced from alpha-pinene, which is abundant in the oils of coniferous trees and can be distilled from turpentine produced as a side product of chemical pulping. With acetic acid as the solvent and with catalysis by a strong acid, alpha-pinene readily rearranges into camphene, which in turn undergoes Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement into the isobornyl cation, which is captured by acetate to give isobornyl acetate. Hydrolysis into isoborneol followed by oxidation gives racemic camphor.

By contrast, camphor occurs naturally as the D-enantiomer.

Biosynthesis

In biosynthesis, camphor is produced from geranyl pyrophosphate, via cyclisation of linaloyl pyrophosphate to bornyl pyrophosphate, followed by hydrolysis to borneol and oxidation to camphor.

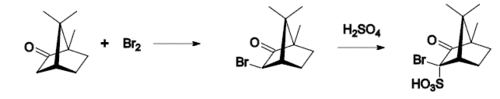

Reactions

Typical camphor reactions are

- oxidation with nitric acid,

- conversion to isonitrosocamphor.

Camphor can also be reduced to isoborneol using sodium borohydride.

In 1998, Kuntal Chakrabarti and his coworkers from the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata, prepared diamond thin film using camphor as the precursor for chemical vapor deposition.[6]

In 2007, carbon nanotubes were successfully synthesized using camphor in chemical vapor deposition process.[7]

Uses

Modern uses include camphor as a plasticizer for nitrocellulose (see Celluloid), as a moth repellent, as an antimicrobial substance, in embalming, and in fireworks. Solid camphor releases fumes that form a rust-preventative coating, and is therefore stored in tool chests to protect tools against rust.[8]

Camphor crystals are also used to prevent damage to insect collections by other small insects, also as a cough suppressant. Some folk remedies state camphor will deter snakes and other reptiles due to its strong odor. Similarly, camphor is believed to be toxic to insects and is thus sometimes used as a repellent.[9]

Culinary

In ancient and medieval Europe, camphor was used as an ingredient in sweets. It was used in a wide variety of both savory and sweet dishes in medieval Arabic language cookbooks, such as al-Kitab al-Ṭabikh compiled by ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq in the 10th century,[10] and an anonymous Andalusian cookbook of the 13th century.[5] It also appears in sweet and savory dishes in a book written in the late 15th century for the sultans of Mandu, the Ni'matnama.[11]

Currently, camphor is used as a flavoring, mostly for sweets, in Asia. It is widely used in cooking, mainly for dessert dishes, in India where it is known as kachha karpooram or "pachha karpoora" ("crude/raw camphor"), in (Telugu:పచ్చ కర్పూర), (Tamil:பச்சைக் கற்பூரம்), (Kannada:ಪಚ್ಚ ಕರ್ಪೂರ), and is available in Indian grocery stores where it is labeled as "Edible Camphor". But in Tamil, rasak karpooram is entirely different and toxic. rasak karpooram is used as insect repellent, safety material for clothes where rasa karpooram is kept between clothes.

Medicinal

Camphor is readily absorbed through the skin and produces a feeling of cooling similar to that of menthol, and acts as slight local anesthetic and antimicrobial substance. There are anti-itch gels and cooling gels with camphor as the active ingredient. Camphor is an active ingredient (along with menthol) in vapor-steam products, such as Vicks VapoRub.

Camphor may also be administered orally in small quantities (50 mg) for minor heart symptoms and fatigue.[12] Through much of the 1900s this was sold under the trade name Musterole; production ceased in the 1990s.

In the 18th century, camphor was used by Auenbrugger in the treatment of mania.[13]

Based on Hahnemann's writings, Camphor (dissolved in alcohol) was also successfully used to treat cholera epidemics in Naples, 1854-1855.[14]

Herbalism

Camphor is available as an essential oil for aromatherapy or topical application.

Hindu religious ceremonies

Camphor is widely used in Hindu religious ceremonies. Hindus worship a holy flame by burning camphor, which forms an important part of many religious ceremonies. Camphor is used in the Mahashivratri celebrations of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and (re)creation. As a natural pitch substance, it burns cool without leaving an ash residue, which symbolizes consciousness. Most temples in southern India have stopped lighting camphor in the main Sanctum Sanctorum because of the heavy carbon deposits it produces; however, open areas still burn it.

In Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala & Andamans, camphor is the prime ingredient in any holy rituals. End of a holy ritual here contains a camphor flame (called Aarti) is shown to deities.

In Hindu pujas and ceremonies, camphor is burned in a ceremonial spoon for performing aarti. This type of camphor, the processed white crystalline kind, is also sold at Indian grocery stores. It is not suitable for cooking, however, and is hazardous to health if eaten.

Toxicology

In larger quantities, camphor is poisonous when ingested and can cause seizures, confusion, irritability, and neuromuscular hyperactivity. In extreme cases, even topical application of camphor may lead to hepatotoxicity.[15][16] Lethal doses in adults are in the range 50–500 mg/kg (orally). Generally, two grams cause serious toxicity and four grams are potentially lethal.[17]

In 1980, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration set a limit of 11% allowable camphor in consumer products, and totally banned products labeled as camphorated oil, camphor oil, camphor liniment, and camphorated liniment (except "white camphor essential oil", which contains no significant amount of camphor). Since alternative treatments exist, medicinal use of camphor is discouraged by the FDA, except for skin-related uses, such as medicated powders, which contain only small amounts of camphor.

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co., Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960

- ^ Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

- ^ Mann JC, Hobbs JB, Banthorpe DV, Harborne JB (1994). Natural products: their chemistry and biological significance. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman Scientific & Technical. pp. 309–11. ISBN 0-582-06009-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Camphor at the Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ a b An Anonymous Andalusian cookbook of the 13th century, translated from the original Arabic by Charles Perry

- ^ >Chakrabarti K,Chakrabarti R, Chattopadhyay KK, Chaudhuri S, Pal AK (1998). "Nano-diamond films produced from CVD of camphor". Diam Relat Mater. 7 (6): 845–52. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(97)00312-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kumar M, Ando Y (2007). "Carbon Nanotubes from Camphor: An Environment-Friendly Nanotechnology". J Phys Conf Ser. 61: 643–6. Bibcode:2007JPhCS..61..643K. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/61/1/129.

- ^ Tips for Cabinet Making Shops

- ^ The Housekeeper's Almanac, or, the Young Wife's Oracle! for 1840!. No. 134. New-York: Elton, 1840. Print.

- ^ Nasrallah, Nawal (2007). Annals of the Caliphs' Kitchens: Ibn Sayyâr al-Warrâq's Tenth-century Baghdadi Cookbook. Islamic History and Civilization, 70. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

- ^ Titley, Norah (2004). The Ni'matnama Manuscript of the Sultans of Mandu: The Sultan's Book of Delights. Routledge Studies in South Asia. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35059-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|middle=ignored (help) - ^ National Agency for Medicines

- ^ Pearce, J M S (2008). "Leopold Auenbrugger: camphor-induced epilepsy – remedy for manic psychosis". Eur. Neurol. 59 (1–2). Switzerland: 105–7. doi:10.1159/000109581. PMID 17934285.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ http://www.legatum.sk/en:ahr:bayes-cholera-as-treated-by-dr-rubini-158-10355 The American Homoeopathic Review Vol. 06 No. 11-12, 1866, pages 401-403

- ^ Martin D, Valdez J, Boren J, Mayersohn M (2004). "Dermal absorption of camphor, menthol, and methyl salicylate in humans". J Clin Pharmacol. 44 (10): 1151–7. doi:10.1177/0091270004268409. PMID 15342616.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uc A, Bishop WP, Sanders KD (2000). "Camphor [[hepatotoxicity]]". South Med J. 93 (6): 596–8. PMID 10881777.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ International Programme on Chemical Safety. Poisons Information Monograph: Camphor. http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/camphor.htm

External links

- Camphor Evidence-based Monograph from Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database

- INCHEM at IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety)