Capitalism: A Love Story

| Capitalism: A Love Story | |

|---|---|

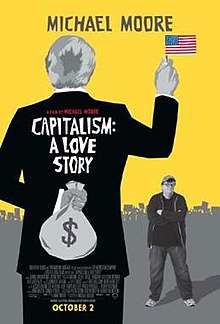

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Moore |

| Written by | Michael Moore |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | Michael Moore |

| Narrated by | Michael Moore |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Jeff Gibbs |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 127 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $20 million |

| Box office | $17.4 million[3] |

Capitalism: A Love Story is a 2009 American documentary film directed, written by, and starring Michael Moore. The film centers on the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the recovery stimulus, while putting forward an indictment of the then-current economic order in the United States and of unfettered capitalism in general. Topics covered include Wall Street's "casino mentality", for-profit prisons, Goldman Sachs' influence in Washington, D.C., the poverty-level wages of many workers, the large wave of home foreclosures, corporate-owned life insurance, and the consequences of "runaway greed".[4] The film also features a religious component in which Moore examines whether or not capitalism is a sin and whether Jesus would be a capitalist;[5] this component highlights Moore's belief that evangelical conservatives contradict themselves by supporting free market ideals while professing to be Christians.

The film was widely released to the public in the United States and Canada on October 2, 2009. Reviews were generally positive. It was released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 9, 2010.

Synopsis

[edit]Moore begins by discussing what capitalism and "free enterprise" mean. Looking back on his happy and prosperous early life, Moore asserts that "if this was capitalism, I loved it... and so did everyone else". Moore states that in the 1950s, the top tax rate was 90% (in his view, this tax rate enabled the U.S. to build dams, bridges, schools and hospitals), most families only had one working parent, union families had free healthcare, college tuition was free, most people had little personal debt and pensions were guaranteed. This prosperity was driven by the manufacturing industry, which benefited from post-war West Germany and Japan struggling to recover. He describes President Jimmy Carter's Crisis of Confidence speech as a turning point that led to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980; Moore calls Reagan a "spokesmodel" for banks and corporations who wanted to remake America to serve their interests.

Moore looks back on his first film, Roger & Me, about the regional economic impact of General Motors CEO Roger Smith's decision to close several auto plants in his hometown of Flint, Michigan despite large profits. He notes that by the time of the job cuts in Flint, Germany and Japan had rebuilt their automotive industries and were producing better, safer, cleaner, more reliable cars.[clarification needed] Moore then returns to the present, showing President George W. Bush enjoying his final year in office as companies announce massive layoffs and the economy starts to collapse.

After seeing the congressional testimony of pilot Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger (who reported that over the course of his career, his salary had been cut by 40 percent and his pension, like most airline pensions, was terminated and replaced by a "PBGC" guarantee worth only pennies on the dollar),[6] Moore notes that pilots being overworked and underpaid did not enter into the media discussion following the crash of Colgan Air Flight 3407. He asserts that capitalism allows people to get away with anything, including making a profit from someone's death. He speaks to the family of a man who worked for Amegy Bank of Texas, which had secretly taken out a life insurance policy on the man with itself as the beneficiary and had then accidentally informed his widow that the bank was receiving a $1.5m payout due to his death of cancer. Moore wonders how the bank's actions can be legal when he himself is prohibited from taking out home insurance on someone else's property.

Moore speaks to Catholic priests and Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, who believes that capitalism is evil and contrary to the teachings of Jesus and the Bible. Moore examines the claim that the tenets of capitalism are compatible with Christianity, arguing that the rich ignore religion when it comes to the poor, sick and disadvantaged. He points to Citigroup's leaked "plutonomy memo", which said that America and other countries were not democracies anymore, but were ruled by the wealthy.

Moore reports on the 2008 presidential campaign of Democratic Senator Barack Obama, who was demonized as a "socialist". He notes that the smears against Obama did not work, as support for him increased and people become curious about what socialism actually meant. He profiles Wayne County Sheriff Warren Evans, who orders an end to foreclosures; the Miami Low Income Families Fighting Together, who re-occupy foreclosed homes; and workers at Republic Windows and Doors, who organized a sit-down strike after being fired without severance, vacation time, or health care benefits after the company was taken over by Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase.

The film ends with Moore marking Wall Street off as a crime scene, opining that American people live in the richest country on Earth and deserve decent jobs, healthcare, good educations and homes of their own. Moore adds that it is a crime that Americans do not have these things and never will have them as long as the evil of capitalism continues to enrich the few at the expense of the many. He calls for capitalism to be eliminated and replaced with something good for all people: Democracy. Moore concludes that he cannot accomplish this goal alone and appeals for help from the viewer, ending the film. He quotes Don Regan's line to Ronald Reagan, "... and please, speed it up".

Participants

[edit]- William K. Black, attorney, academic, author and former bank regulator

- Elijah Cummings, U.S. Representative (D-MD)

- Warren Evans, Wayne County Sheriff

- Thomas Gumbleton, retired Roman Catholic auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Detroit

- Baron Hill, U.S. Representative (D-IN)

- Marcy Kaptur, U.S. Representative (D-OH)

- Stephen Moore, economic writer and policy analyst (no relation to Michael Moore)

- Bernie Sanders, U.S. Senator (I-VT)

- Wallace Shawn, actor

- Elizabeth Warren, U.S. Senator (D-MA), Chair of the Congressional Oversight Panel and bankruptcy law scholar at Harvard Law School

Production

[edit]During the Cannes Film Festival in 2008, Overture Films and Paramount Vantage announced an upcoming project by director Michael Moore, though at the time they were vague about the project's theme. Originally thought to be a follow-up to the 2004 film Fahrenheit 9/11, it was revealed that Moore's film was to be a documentary about the 2007–2008 financial crisis. In February 2009, he issued an appeal to people who worked for Wall Street or in the financial industry to share firsthand information, requesting, "Be a hero and help me expose the biggest swindle in American history."[7]

Prior to the film's release, Moore partnered with web development company Concentric Sky to develop a companion website for the film.[8]

Footage of President Franklin D. Roosevelt detailing his proposed Second Bill of Rights was believed to be lost. Roosevelt, who had recently recovered from the flu, presented his January 1944 State of the Union address to the public on radio, as a fireside chat from the White House. He asked that newsreel cameras film the last portion of the address, concerning the Second Bill of Rights. This footage was believed lost until it was uncovered in 2008 in South Carolina by Michael Moore while researching for the film.[9] The footage shows Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights address in its entirety, as well as a shot of the eight rights printed on a sheet of paper.[10][11]

Release

[edit]Theatrical run

[edit]Capitalism: A Love Story premiered at the 66th Venice International Film Festival on September 6, 2009.[12] The film also screened at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 13 and at the New York Film Festival on September 21. On September 23, the film had a limited release at two theaters in New York City and two theaters in Los Angeles,[13] grossing $37,832 in its first day for a $9,458 per theater average.[14] The theater average was considered strong, though it did not beat the record opening of Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11, which grossed $83,922 at two theaters in one day.[13] Over the weekend of September 25, Capitalism grossed $231,964 in the four theaters.[15]

The film had a wide release in 995 theaters in the United States and Canada on October 2, 2009,[3] about a year after the enacting of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which approved a $700 billion bailout of Wall Street.[7] The film opened in eighth place at the box office on the first weekend of its wide release, grossing $4,447,378.[16] The final domestic total was $14,363,397,[3] making it the 16th highest grossing documentary in history (2014).[17]

Critical reception

[edit]Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported an approval rating of 75% based on 185 reviews, with an average score of 6.71 out of 10. The site's critics' consensus reads: "Love him or hate him, Capitalism captures Michael Moore in his muckraking element -- with all the Moore-centric showmanship that entails."[18] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average rating out of 100 to mainstream critics' reviews, reported an average score of 61 out of 100 based on 35 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[19]

Deborah Young, writing for the trade paper The Hollywood Reporter, wrote of Capitalism: A Love Story, "Although it's less focused than Sicko or Fahrenheit 9/11... because its subject is more abstract, this is a typical Moore oeuvre: funny, often over the top and of dubious documentation, but with strongly made points that leave viewers much to ponder and debate after they walk out of the theater." Young acknowledged Moore's simplification of the topic and added, "But here his talent is evident in creating two hours of engrossing cinema by contrasting a fast-moving montage of '50s archive images extolling free enterprise with the economic disaster of the present." The critic noted whom the documentary targeted: "Though it blames all political parties, including the Democrats, for caving in with the bailout, the film is careful to spare President Barack Obama, who remains a symbol of hope for justice."[20]

Leslie Felperin of the trade paper Variety wrote, "Pic's target is less capitalism qua capitalism than the banking industry, which Moore skewers ruthlessly, explaining last year's economic meltdown in terms a sixth-grader could understand. That said, there's still plenty here to annoy right-wingers, as well as those who, however much they agree with Moore's politics, just can't stomach his oversimplification, on-the-nose sentimentality and goofball japery." Felperin said that the documentary was similarly structured to Moore's previous documentaries, "Capitalism skips around considerably, laying down a mix of reportage, interviews and polemic." Felperin observed Moore's prominent role in his own documentary, believing it to be justified with relevance to crises in the automobile industry that Moore's family personally encountered. The critic complained that Moore strove "to manipulate viewers' emotions with shots of crying children and tearjerking musical choices", believing that the documentary worked better when the director let the topic unfold through various accounts.[21]

Upon the film's February 2010 UK release, The Times said the film "showcases Moore at his undeniably powerful best and his exploitative, manipulative worst":[22]

The film is brilliantly researched, both with regard to the labyrinthine web of connections between the world of finance and the corridors of power and the wittily used archive footage. Interviews with Senate insiders and financial experts are informative, and there’s an amusing sequence in which he quizzes a selection of priests and bishops who opine that capitalism is "evil" and was not, in fact, the preferred economic model of Our Lord. Then Moore goes and spoils it all by hauling out his trusty bullhorn for a series of lame stunts. Like the complacent clown prince of agitprop, Moore hectors Wall Street doormen and security guards, while the company bosses remain in their fortress made of money, blissfully unaware of the fat man making a scene on the street far below....But for all his cheap tactics, Moore mounts a persuasive case that something is rotten in the current economic system.

Topical accuracy

[edit]The Associated Press's national business columnist Rachel Beck reviewed the accuracy of three points made in Capitalism:

- Three months after a scene in which Moore approaches Goldman Sachs headquarters to reclaim taxpayers' funds, the bank was one of the ten that repaid part of the $68 billion received from the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Moore responded to the action: "We're not talking about the majority of people who took the money ... not even 10 percent of the $700 billion has been returned."[23]

- Moore criticizes Wal-Mart for "dead peasant" policies, all 350,000 of which were cancelled in 2000. However, Moore notes that the termination of the policies was covered in the presentation of facts and quotes in the closing credits.[23]

- The documentary criticizes Senator Christopher Dodd and other government officials for benefiting from exclusive financial programs; Moore lambasts Dodd in particular for predatory lending as chairman of the Senate Banking Committee. The AP reported that the interest rates and fees involved were norms for the industry, and that the Senate's Select Committee on Ethics cleared Dodd and Kent Conrad of getting special treatments, but it cautioned the senators to exercise "more vigilance" with such deals.[23]

The Association of Advanced Life Underwriting issued a statement that Moore "mischaracterized" Corporate Owned Life Insurance (COLI), stating that the issues were addressed by Congress in the 1990s and again in 2006. The AALU further states that corporate-owned life insurance is taken out only on highly compensated employees, only with their knowledge and consent and that COLI finances employee benefits and protects jobs and that employees pay nothing for COLI but receive substantial benefits.[24]

Religious subject matter

[edit]Religion expert Anthony Stevens-Arroyo stated that the film should be considered "a special kind of Catholic achievement" and asked whether Michael Moore should be named "Catholic of the Year" for raising the serious issues in the context of Catholic social teaching, and for presenting "Catholic currents of social justice" in the film.[25]

Awards and honors

[edit]At the Venice Film Festival, Moore won the "Leoncino d'Oro" ("Little Golden Lion") award for his documentary, and he also received the festival's Open Prize.[26] The documentary was also nominated for the festival's Golden Lion award,[27] but lost to Lebanon.[28] Moore also received a nomination for Best Documentary Screenplay from the Writers Guild of America.[29] At the 15th Critics' Choice Awards, it received a nomination for Best Documentary Feature.[30]

See also

[edit]- 2007–2008 financial crisis

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

- Troubled Asset Relief Program

- Wall Street reform

- Eye of a needle

- Christian views on poverty and wealth

- List of films about socialism

- Related films

References

[edit]- ^ Kay, Jeremy (May 13, 2008). "Paramount Vantage, Overture to co-finance, distribute Moore's next". Screen International. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "CAPITALISM: A LOVE STORY (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. October 13, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Capitalism: A Love Story (2009)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ Huffington, Arianna (September 21, 2009). "Barack Obama Must See Michael Moore's New Movie (and So Must You)!". The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Michael (October 4, 2009). "For Those of You on Your Way to Church This Morning ..." The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ US Airways Flight 1549 Accident, Hearing. February 24, 2009. U.S. House, Subcommittee on Aviation, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. Washington: Government Printing Office, 2009.

- ^ a b Dave McNary (July 8, 2009). "Michael Moore unveils title of new doc". Variety. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ "Web firm lands big contract". The Register-Guard. October 10, 2009.

- ^ "The Best Scenes From Michael Moore's New Movie". The Daily Beast. September 22, 2009. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Capitalism: A Love Story at IMDb (starting approximately at time code 1:55:00)

- ^ Moore, Michael; et al. (2010). Capitalism: A Love Story (DVD). Traverse City, MI: Front Street Productions, LLC. OCLC 443524847. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (September 1, 2009). "Stars to shine on Lido". Variety. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Fritz, Ben (September 24, 2009). "Moore's 'Capitalism' off to profitable start". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ "Capitalism: A Love Story (2009) – Daily Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ "Capitalism: A Love Story (2009) – Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for October 2–4, 2009". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ "Documentary Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ "Capitalism: A Love Story (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "Capitalism: A Love Story Review". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Young, Deborah (September 6, 2009). "Capitalism: A Love Story — Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (September 5, 2009). "Capitalism: A Love Story". Variety. Time. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ Ide, Wendy (February 26, 2010). "Capitalism: A Love Story". The Times. Times Newspapers. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c Beck, Rachel (September 24, 2009). "Fact-checking Moore's 'Capitalism'". CBS News. Associated Press. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ [1] Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Washington Post, October 28, 2009, "Catholic America: Michael Moore: Catholic of the year?" [2]

- ^ "La Biennale di Venezia - The 66th Festival Collateral Awards". labiennale.org. September 12, 2009. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ O'Neil, Tom (July 30, 2009). "Venice Film Festival unveils Golden Lion lineup led by Michael Moore". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ "Top Venice award for Israeli film". news.bbc.co.uk. BBC. September 12, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ "2010 Writers Guild Award Winners". TV Source Magazine. February 21, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "15th Annual Critics' Choice Movie Awards (2010) – Best Picture: The Hurt Locker". Critics Choice. November 21, 2011. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Capitalism: A Love Story at IMDb

- Capitalism: A Love Story at Box Office Mojo

- Capitalism: A Love Story at Rotten Tomatoes

- Capitalism: A Love Story at Metacritic

- Michael Moore (October 22, 2009). "Post-Film Action Plan: 15 Things Every American Can Do Right Now". The Huffington Post.

- Chris McGreal (January 30, 2010). "Capitalism is evil … you have to eliminate it". The Guardian. London. An in-depth review and analysis from the Guardian.

- Multimedia

- In The Center Ring: Michael Moore vs Capitalism - audio report by NPR

- Michael Moore: "Capitalism Has Failed" - interviewed by CNN's Larry King Live is here

- Capitalism's Enemy, Michael Moore - video report by The Colbert Report

- Naomi Klein in Conversation With Michael Moore Archived September 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine - audio report by The Nation

- Michael Moore Examines Today's Economic State - video report by the Tavis Smiley Show

- Moore Goes to the Source in "Capitalism: A Love Story" - a 45-minute video report by Democracy Now!, September 24, 2008

- 2009 films

- 2000s Russian-language films

- 2000s Spanish-language films

- 2009 documentary films

- American documentary films

- Works about capitalism

- Anti-capitalism

- Documentary films about American politicians

- Documentary films about businesspeople

- Documentary films about ideologies

- Documentary films about the Great Recession

- Films directed by Michael Moore

- Films about financial crises

- Wall Street films

- The Weinstein Company films

- Overture Films films

- Films set in Michigan

- Documentary films about American politics

- Documentary films about the automotive industry

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- English-language documentary films