Carbonyl group

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups.

The term carbonyl can also refer to carbon monoxide as a ligand in an inorganic or organometallic complex (a metal carbonyl, e.g. nickel carbonyl).

The remainder of this article concerns itself with the organic chemistry definition of carbonyl, where carbon and oxygen share a double bond.

Carbonyl compounds

A carbonyl group characterizes the following types of compounds:

| Compound | Aldehyde | Ketone | Carboxylic acid | Ester | Amide |

| Structure |  |

|

| ||

| General formula | RCHO | RCOR' | RCOOH | RCOOR' | RCONR'R'' |

| Compound | Enone | Acyl halide | Acid anhydride | Imide |

| Structure |  |

Acyl chloride |  |

|

| General formula | RC(O)C(R')CR''R''' | RCOX | (RCO)2O | RC(O)N(R')C(O)R''' |

Note that the most specific labels are usually employed. For example, R(CO)O(CO)R' structures are known as acid anhydride rather than the more generic ester, even though the ester motif is present.

Other organic carbonyls are urea and the carbamates, the derivatives of acyl chlorides chloroformates and phosgene, carbonate esters, thioesters, lactones, lactams, hydroxamates, and isocyanates. Examples of inorganic carbonyl compounds are carbon dioxide and carbonyl sulfide.

A special group of carbonyl compounds are 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds that have acidic protons in the central methylene unit. Examples are Meldrum's acid, diethyl malonate and acetylacetone.

Reactivity

Oxygen is more electronegative than carbon, and thus draws electron density away from carbon to increase the bond's polarity. Therefore, the carbonyl carbon becomes electrophilic, and thus more reactive with nucleophiles. Also, the electronegative oxygen can react with an electrophile; for example a proton in an acidic solution or other Lewis Acid forming a oxocarbenium ion.

The alpha hydrogens of a carbonyl compound are much more acidic (~103 times more acidic) than a typical C-H bond. For example, the pKa values of acetaldehyde and acetone are 16.7 and 19, respectively.[1] This is because a carbonyl is in tautomeric resonance with an enol. The deprotonation of the enol with a strong base produces an enolate, which is a powerful nucleophile and can alkylate electrophiles such as other carbonyls.

Amides are the most stable of the carbonyl couplings due to their high resonance stabilization between the nitrogen-carbon and carbon-oxygen bonds.

Carbonyl groups can be reduced by reaction with hydride reagents such as NaBH4 and LiAlH4, or catalytically by hydrogen and a catalyst such as copper chromite, Raney nickel, rhenium, ruthenium or even rhodium. Ketones give secondary alcohols; aldehydes, esters and carboxylic acids give primary alcohols.

Carbonyls would be alkylated by nucleophilic attack by organometallic reagents such as organolithium reagents and Grignard reagents. Carbonyls also may be alkylated by enolates as in aldol reactions. Carbonyls are also the prototypical groups with vinylogous reactivity, e.g. the Michael reaction where an unsaturated carbon in conjugation with the carbonyl is alkylated instead of the carbonyl itself.

Other important reactions include:

- Wittig Reaction a phosphonium ylid is used to create an alkene

- Wolff-Kishner reduction into a hydrazone and further into a saturated alkane

- Clemmensen reduction into a saturated alkane

- Mozingo reduction into a saturated alkane

- Conversion into thioacetals

- Hydration to hemiacetals and hemiketals, and then to acetals and ketals

- Reaction with ammonia and primary amines to form imines

- Reaction with hydroxylamines to form oximes

- Reaction with cyanide anion to form cyanohydrins

- Oxidation with oxaziridines to acyloins

- Reaction with Tebbe's reagent and phosphonium ylides to alkenes.

- Perkin reaction, an aldol reaction variant

- Aldol condensation, a reaction between an enolate and a carbonyl

- Cannizzaro reaction, a disproportionation of aldehydes into alcohols and acids

- Tishchenko reaction, another disproportionation of aldehydes that gives a dimeric ester

- Nucleophilic abstraction is used to produce carbon dioxide

α,β-Unsaturated carbonyl compounds

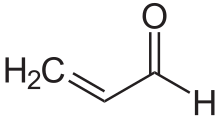

α,β-Unsaturated carbonyl compounds are an important class of carbonyl compounds with the general structure −(O=C)−Cα=Cβ−. In these compounds the carbonyl group is conjugated with an alkene (hence the adjective unsaturated), from which they derive special properties. Unlike the case for simple carbonyls, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds are often attacked by nucleophiles at the β carbon. This pattern of reactivity is called vinylogous. Examples of unsaturated carbonyls are acrolein (propenal), mesityl oxide, acrylic acid, and maleic acid. Unsaturated carbonyls can be prepared in the laboratory in an aldol reaction and in the Perkin reaction.

The carbonyl group draws electrons away from the alkene, and the alkene group is, therefore, deactivated towards an electrophile, such as bromine or hydrochloric acid. As a general rule with asymmetric electrophiles, hydrogen attaches itself at the α-position in an electrophilic addition. On the other hand, these compounds are activated towards nucleophiles in nucleophilic conjugate addition.

Since α,β-unsaturated compounds are electrophiles, many α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds are toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic. DNA can attack the β carbon and thus be alkylated. However, the endogenous scavenger compound glutathione naturally protects from toxic electrophiles in the body.

Spectroscopy

- Infrared spectroscopy: the C=O double bond absorbs infrared light at wavenumbers between approximately 1600–1900 cm−1. The exact location of the absorption is well understood with respect to the geometry of the molecule. This absorption is known as the "carbonyl stretch" when displayed on an infrared absorption spectrum.[2]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance: the C=O double-bond exhibits different resonances depending on surrounding atoms, generally a downfield shift. The 13C NMR of a carbonyl carbon is in the range of 160-220 ppm.

See also

References

Further reading

- L.G. Wade, Jr. Organic Chemistry, 5th ed. Prentice Hall, 2002. ISBN 0-13-033832-X

- The Frostburg State University Chemistry Department. Organic Chemistry Help (2000).

- Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc. IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry (1997).

- William Reusch. tara VirtualText of Organic Chemistry (2004).

- Purdue Chemistry Department [1] (retrieved Sep 2006). Includes water solubility data.

- William Reusch. (2004) Aldehydes and Ketones Retrieved 23 May 2005.

- ILPI. (2005) The MSDS Hyperglossary- Anhydride.