Carl Sandburg

Carl Sandburg | |

|---|---|

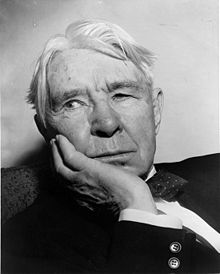

Sandburg in 1955 | |

| Born | Carl August Sandburg[1] January 6, 1878 Galesburg, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | July 22, 1967 (aged 89) Flat Rock, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Lombard College (non-graduate) |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Lilian Steichen |

| Children | 3 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1898 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | Company C, 6th Illinois Infantry Regiment |

| Battles / wars | Spanish–American War |

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, writer, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg was widely regarded as "a major figure in contemporary literature", especially for volumes of his collected verse, including Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920).[2] He enjoyed "unrivaled appeal as a poet in his day, perhaps because the breadth of his experiences connected him with so many strands of American life",[3] and at his death in 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson observed that "Carl Sandburg was more than the voice of America, more than the poet of its strength and genius. He was America."[4]

Life

Carl Sandburg was born in a three-room cottage at 313 East Third Street in Galesburg, Illinois, to Clara Mathilda (née Anderson) and August Sandberg,[1] both of Swedish ancestry.[5] He adopted the nickname "Charles" or "Charlie" in elementary school at about the same time he and his two oldest siblings changed the spelling of their last name to "Sandburg".[1][6][7]

At the age of thirteen he left school and began driving a milk wagon. From the age of about fourteen until he was seventeen or eighteen, he worked as a porter at the Union Hotel barbershop in Galesburg.[8] After that he was on the milk route again for eighteen months. He then became a bricklayer and a farm laborer on the wheat plains of Kansas.[9] After an interval spent at Lombard College in Galesburg,[10] he became a hotel servant in Denver, then a coal-heaver in Omaha. He began his writing career as a journalist for the Chicago Daily News. Later he wrote poetry, history, biographies, novels, children's literature, and film reviews. Sandburg also collected and edited books of ballads and folklore. He spent most of his life in the Midwest before moving to North Carolina.

Sandburg volunteered to go to the military and was stationed in Puerto Rico with the 6th Illinois Infantry during the Spanish–American War,[11] disembarking at Guánica, Puerto Rico on July 25, 1898. Sandburg was never actually called to battle. He attended West Point for just two weeks, before failing a mathematics and grammar exam. Sandburg returned to Galesburg and entered Lombard College, but left without a degree in 1903. He then moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and joined the Social Democratic Party, the name by which the Socialist Party of America was known in the state. Sandburg served as a secretary to Emil Seidel, socialist mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912.[12]

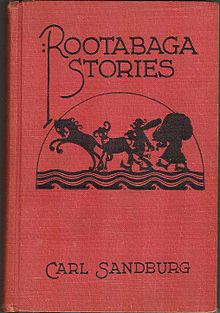

Sandburg met Lilian Steichen (1883-1977) at the Social Democratic Party office in 1907, and they married the next year. Lilian's brother was the photographer Edward Steichen. Sandburg with his wife, whom he called Paula, raised three daughters. The Sandburgs moved to Harbert, Michigan, and then to suburban Chicago, Illinois. They lived in Evanston, Illinois, before settling at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst, Illinois, from 1919 to 1930. During the time, Sandburg wrote Chicago Poems (1916), Cornhuskers (1918), and Smoke and Steel (1920).[2] In 1919 Sandburg won a Pulitzer Prize "made possible by a special grant from The Poetry Society" for his collection Cornhuskers.[13] Sandburg also wrote three children's books in Elmhurst: Rootabaga Stories, in 1922, followed by Rootabaga Pigeons (1923), and Potato Face (1930). Sandburg also wrote Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years, a two-volume biography, in 1926, The American Songbag (1927), and a book of poems called Good Morning, America (1928) in Elmhurst.

The family moved to Michigan in 1930, and the Sandburg house at 331 South York Street in Elmhurst was demolished and the site is now a parking lot. Sandburg won the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for History for the four-volume The War Years, the sequel to his Abraham Lincoln, and a second Poetry Pulitzer in 1951 for Complete Poems.[13][14][note 1]

In 1945 he moved to Connemara, a 246-acre (100 ha) rural estate in Flat Rock, North Carolina. Here he produced a little over a third of his total published work, and lived with his wife, daughters, and two grandchildren.[15]

On February 12, 1959, in commemorations of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth, Congress met in joint session to hear actor Fredric March give a dramatic reading of the Gettysburg Address, followed by an address by Sandburg.[16] As of 2013[update], Sandburg remains the only Swedish-American or American poet ever invited to address a joint session of Congress.[17]

Sandburg supported the Civil Rights Movement and was the first white man to be honored by the NAACP with their Silver Plaque Award as a "major prophet of civil rights in our time."[18]

Sandburg died of natural causes in 1967 and his body was cremated. The ashes were interred under "Remembrance Rock", a granite boulder located behind his birth house.[19][note 2]

Career

Poetry and prose

Much of Carl Sandburg's poetry, such as "Chicago", focused on Chicago, Illinois, where he spent time as a reporter for the Chicago Daily News and the Day Book. His most famous description of the city is as "Hog Butcher for the World/Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat/Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler,/Stormy, Husky, Brawling, City of the Big Shoulders."

Sandburg earned Pulitzer Prizes for his collection The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg, Corn Huskers, and for his biography of Abraham Lincoln (Abraham Lincoln: The War Years).[14] He recorded excerpts from the biography and some of Lincoln's speeches for Caedmon Records in New York City in May 1957. He was awarded a Grammy Award in 1959 for Best Performance – Documentary Or Spoken Word (Other Than Comedy) for his recording of Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait with the New York Philharmonic.

Sandburg is also remembered by generations of children for his Rootabaga Stories and Rootabaga Pigeons, a series of whimsical, sometimes melancholy stories he originally created for his own daughters. The Rootabaga Stories were born of Sandburg's desire for "American fairy tales" to match American childhood. He felt that the European stories involving royalty and knights were inappropriate, and so populated his stories with skyscrapers, trains, corn fairies and the "Five Marvelous Pretzels".

Folk music

Sandburg's 1927 anthology, the American Songbag, enjoyed enormous popularity, going through many editions; and Sandburg himself was perhaps the first American urban folk singer, accompanying himself on solo guitar at lectures and poetry recitals, and in recordings, long before the first or the second folk revival movements (of the 1940s and 1960s, respectively).[21] According to the musicologist Judith Tick:

As a populist poet, Sandburg bestowed a powerful dignity on what the '20s called the "American scene" in a book he called a "ragbag of stripes and streaks of color from nearly all ends of the earth ... rich with the diversity of the United States." Reviewed widely in journals ranging from the New Masses to Modern Music, the American Songbag influenced a number of musicians. Pete Seeger, who calls it a "landmark", saw it "almost as soon as it came out." The composer Elie Siegmeister took it to Paris with him in 1927, and he and his wife Hannah "were always singing these songs. That was home. That was where we belonged."[22]

Legacy

Commemoration

Carl Sandburg's boyhood home in Galesburg is now operated by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency as the Carl Sandburg State Historic Site. The site contains the cottage Sandburg was born in, a modern visitor's center, and small garden with a large stone called Remembrance Rock, under which his and his wife's ashes are buried.[23] Sandburg's home of 22 years in Flat Rock, Henderson County, North Carolina, is preserved by the National Park Service as the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Carl Sandburg College is located in Sandburg's birthplace of Galesburg, Illinois.

On January 6, 1978, the 100th anniversary of his birth, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Sandburg. The spare design consists of a profile originally drawn by his friend William A. Smith in 1952, along with Sandburg's own distinctive autograph.[24]

The Rare Book & Manuscript Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) (RBML)[25] houses the Carl Sandburg Papers. The bulk of the collection was purchased directly from Carl Sandburg and his family. In total, the RBML owns over 600 cubic feet of Sandburg's papers, including photographs, correspondence, and manuscripts.[26][27]

In 2011, Sandburg was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[28]

Namesakes

Carl Sandburg Village was a Chicago urban renewal project of the 1960s located in the Near North Side, Chicago. Financed by the city, it is located between Clark and LaSalle St. between Division Street and North Ave. Solomon & Cordwell, architects. In 1979, Carl Sandburg Village was converted to condominium ownership.

In 1960, Elmhurst, Illinois renamed the former Elmhurst Junior High School as "Carl Sandburg Middle School." Sandburg spoke at the dedication ceremony. He resided at 331 S. York Street in Elmhurst from 1919 to 1930. The house was demolished and the site is a parking lot.[29] In 1954, Carl Sandburg High School was dedicated in Orland Park, Illinois. Sandburg was in attendance, and stretched what was supposed to be a one-hour event into several hours, regaling students with songs and stories. Years later, he returned to the school with no identification and, appearing to be a hobo, was thrown out by the principal. When he later returned with I.D., the embarrassed principal canceled the rest of the school day and held an assembly to honor the visit.[citation needed] In 1959, Carl Sandburg Junior High School was opened in Golden Valley, Minnesota. Carl Sandburg attended the dedication of the school. In 1988 the name was changed to Sandburg Middle School servicing grades 6, 7, and 8. The school was built with a capacity for 1,800 students. Sandburg Middle school was one of the first schools in the state of Minnesota to offer accelerated learning programs for gifted students. The middle school closed in 2010 and now operates as the Sandburg Learning Center, specializing in adult education. In December 1961, Carl Sandburg Elementary School was dedicated in San Bruno, California. Again, Sandburg came for the ceremonies and was clearly impressed with the faces of the young children, who gathered around him.[30] The school was closed in the 1980s, due to falling enrollments in the San Bruno Park School District. Also, Carl Sandburg Grade school, constructed in 1960's Charleston Illinois, shares in the legacy of Mr. Sandburg.

A school named Carl Sandburg Middle School is located in Neshaminy School District of lower Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Another secondary school by the same name is located south of Alexandria, Virginia, and is part of the Fairfax County Public Schools School District. Sandburg Halls is a student residence hall at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. The building consists of four high-rise towers with a total housing capacity of 2,700 students. It has an exterior plaque on Sandburg's roles as an organizer for the Social Democratic Party and as personal secretary to Emil Seidel, Milwaukee's first Socialist mayor. There are several other schools named after Sandburg in Illinois, including those in Wheaton, Orland Park, Springfield, Mundelein, Freeport and Joliet. Sandburg Elementary School of the San Diego (California) Unified School District is named for Carl Sandburg since its first day and prominently displays its name as Carl Sandburg Elementary School, literally cast in concrete.[31]

Carl Sandburg Library first opened in Livonia, Michigan, on December 10, 1961. The name was recommended by the Library Commission as an example of an American author representing the best of literature of the Midwest. Carl Sandburg had taught at the University of Michigan for a time.[32]

Galesburg opened Sandburg Mall in 1974, named in honor of Sandburg. The Chicago Public Library installed the Carl Sandburg Award, annually awarded for contributions to literature.[33]

Amtrak added the Carl Sandburg train in 2006 to supplement the Illinois Zephyr on the Chicago–Quincy route.[34]

In other media

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

- NBC produced a 6-episode miniseries entitled Lincoln, also referred to as Carl Sandburg's Lincoln, starring Hal Holbrook and directed by George Schaefer, aired between 1974 and 1976.

- Richard Armour's poem "Driving in a Fog; or Carl Sandburg Must Have Been a Pedestrian" published in the January 1953 Westways.

- William Saroyan wrote a short story about Sandburg in his 1971 book, Letters from 74 rue Taitbout or Don't Go But If You Must Say Hello To Everybody.

- Thomas Hart Benton painted a portrait Carl Sandburg in 1956, for which the poet had posed.

- Sandburg's "Sometime they'll give a war and nobody will come" from The People, Yes was a slogan of the German peace movement "Stell dir vor, es ist Krieg, und keiner geht hin", however often attributed to Bertolt Brecht.[35]

- Daniel Steven Crafts' The Song and The Slogan is an orchestral composition built around recited passages from Sandburg's "Prairie".

- Dan Zanes's Parades and Panoramas: 25 Songs Collected by Carl Sandburg for the American Songbag.

- Peter Louis van Dijk's "Windy City Songs", based on the Chicago poems was performed by the Chicago Children's Choir and the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Choir in 2007.[citation needed]

- Steven Spielberg claimed that the face of E.T. was based on a composite of Sandburg, Ernest Hemingway, and Albert Einstein.[36]

- Bob Gibson's "The Courtship of Carl Sandburg", starring Tom Amandes as Sandburg[37]

- Samuel M. Steward's gay pulp collection "$tud"'s protagonist refers to Sandburg in an ironic nod to his commentary on the "painted women of Chicago" (as Steward contrarily wrote of the "male whores" of Chicago).[38]

- In Jonathan Lethem's novel Dissident Gardens the main character Rose Zimmer became an Abraham Lincoln devotee after reading Sandburg's biography. Her copy of the six volumes became the centerpiece of her shrine to Lincoln.

- Sufjan Stevens's "Come on! Feel the Illinoise! Part I: The Columbian Exposition Part II: Carl Sandburg Visits Me in a Dream" (from Illinois).

Bibliography

|

|

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ The Pulitzer Prize for Poetry was inaugurated in 1922 but the organization now considers the first winners to be three recipients of 1918 and 1919 special awards.

- ^ His wife and two daughters would also be interred there. See the signage.

Notes

- ^ a b c Sandburg, Carl (1953). Always the Young Strangers. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 29, 39. Sandburg's father's last name was originally "Danielson" or "Sturm". He could read but not write, and he accepted whatever spelling other people used. The young Carl, sister Mary, and brother Mart changed the spelling to "Sandburg" when in elementary school.

- ^ a b Danilov, Victor (September 26, 2013). Famous Americans: A Directory of Museums, Historic Sites, and Memorials. Scarecrow Press. p. 198. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Heitman, Danny (March–April 2013). "A Workingman's Poet". Humanities. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Callahan, North (October 1, 1990). Carl Sandburg: His Life and Works. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0271004860. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h3767.html

- ^ Sandburg in 1953 was not able to recall his younger self's reasons, but he relates that being able to correctly pronounce "ch" was a mark of assimilation among Swedish immigrants.

- ^ Penelope Niven (2012-08-18). "American Masters: Carl Sandburg Timeline". PBS. Retrieved 2014-01-19.

- ^ Prairie-Town Boy, by Carl Sandburg, 1955. "timforsythe.com"

- ^ Selected Poems of Carl Sandburg, edited by Rebecca West, 1954

- ^ Carl Sandburg College. "History" Archived 2013-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ *Mason, Jr., Herbert Molloy (1999). Kolb, Richard K. (ed.). VFW: Our First Century. Lenexa, Kansas: Addax Publishing Group. pp. 13, 90. ISBN 1-88611072-7. LCCN 99-24943.

- ^ "Revolt Develops Poet", The Western Comrade, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1914), pg. 23.

- ^ a b "Poetry". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ^ a b "12 Search Results". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Sandburg Grandchildren - Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- ^ "Nation Honor Lincoln On Sesquicentennial" (PDF). Yonkers Herald-Statesman. Northern Illinois University Libraries. Associated Press. February 11, 1959. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

Congress gets into the act tomorrow, when a joint session will be held. Carl Sandburg, famed Lincoln biographer, will give and address, and actor Fredric March will read the Gettysburg Address.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Epstein, Joseph (May 1992). "The People's Poet". Commentary. Retrieved January 7, 2015. "Carl Sandburg is the only American poet ever asked to address Congress, a date he was able to fit into his crowded schedule in 1959. He also appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, the Texaco Hour (with Milton Berle), the early Today Show (with Dave Garroway), and See It Now, where he was interviewed by Edward R. Murrow. Sandburg once wrote a poem to which, on television, Gene Kelly danced.The house in which he was born was preserved as a memorial to him when he was still alive."

- ^ "Carl Sandburg cited by NAACP". Baltimore Afro-American. 30 November 1965.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg's ashes placed under Remembrance Rock". The New York Times. 2 October 1967. p. 61.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg House". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2008-10-24.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bill C. Malone and David Stricklin (2003). Southern Music/American Music (University Press of Kentucky, 2003), p. 33.

- ^ Judith Tick, Ruth Crawford Seeger, A Composer's Search for American Music (Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 57

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Historic Site Association". Sandburg.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Scott catalogue

- ^ "Rare Book and Manuscript Library". Library.uiuc.edu. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Papers (Ashville accession)". library.illinois.edu. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Papers (Connemara accession)". library.illinois.edu. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Carl Sandburg". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2011. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

- ^ Elmhurst Historic Archives. "Sandburg" Archived 2007-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ San Bruno Herald

- ^ https://www.sandiegounified.org/schools/sandburg/history-sandburg-elementary (retrieved 2 September 2017)

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Library Homepage". Livonia.lib.mi.us. 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "October 23 Dinner Honors Allende, Lewis and Sneed". Chicago Public Library. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Amtrak Press Release, October 8, 2006. Amtrak.com.

- ^ "von Brecht?". Die Zeit. 2004-08-12.

- ^ Taylor, Philip M. (1992). Steven Spielberg. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-6693-6. p. 134.

- ^ "Bob Gibson's 'The Courtship of Carl Sandburg'" lyon.edu Archived January 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Steward, Samuel M. (1966). $tud. Boston: Alyson Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-932870-02-5. p.151

- ^ "Carl Sandburg Sings On WMAQ Today". The Milwaukee Journal. 10 January 1928. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ "The American Songbag (1927)". Archive.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

Further reading

- Niven, Penelope. Carl Sandburg: A Biography. New York: Scribner's, 1991.

- Sandburg, Carl. The letters of Carl Sandburg. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968.

- Sandburg, Helga. A Great and Glorious Romance: The Story of Carl Sandburg and Lilian Steichen. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

External links

- Carl Sandburg's birthplace in Galesburg, IL

- Carl Sandburg Home, North Carolina from the National Park Service

- Works by Carl Sandburg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl Sandburg at the Internet Archive

- Works by Carl Sandburg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Day Carl Sandburg Died, PBS American Masters video

- Prayers for the People: Carl Sandburg's Poetry and Songs, a Nebraska Educational Telecommunications film, University of Nebraska (video, 1 hour)

- Carl Sandburg databases from the University of Illinois

- Carl Sandburg from the FBI website

- Previously unknown Sandburg poem focuses on power of the gun

- Oliver Barrett-Carl Sandburg Papers at Newberry Library

- Heitman, Danny (March–April 2013). "A Workingman's Poet". Humanities. 34 (2). National Endowment For The Humanities. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Carl Sandburg at Library of Congress, with 276 library catalog records

- Helga Sandburg at LC Authorities, with 20 records

- Carl Sandburg Home NHS images on Open Parks Network

- North Carolina Writers Photographs Collection, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

- Sandburg Series in the Harry Golden papers, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

- Carl Sandburg at Find a Grave

- Articles with trivia sections from January 2017

- 1878 births

- 1967 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century biographers

- American biographers

- American folk-song collectors

- American historians

- American male novelists

- American male poets

- American military personnel of the Spanish–American War

- American people of Swedish descent

- Grammy Award winners

- Historians of the United States

- House of Vasa

- Industrial Workers of the World members

- Lombard College alumni

- Members of the Socialist Party of America

- North American democratic socialists

- People from Elmhurst, Illinois

- People from Galesburg, Illinois

- Poets from North Carolina

- Poets from Wisconsin

- Self-published authors

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Pulitzer Prize for History winners

- Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners

- Writers from Chicago

- Wisconsin State Federation of Labor people

- Poets Laureate of Illinois

- 20th-century American male writers

- Novelists from Illinois

- People from Flat Rock, Henderson County, North Carolina

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers