Chapultepec

| Bosque de Chapultepec | |

|---|---|

Overlooking the Lago Menor towards Polanco. | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico City, Mexico |

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is the largest city park in the Western Hemisphere, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultepec Hill, one of the park's main functions is to be an ecological space in the vast megalopolis. It is considered the first and most important of Mexico City's "lungs", with trees that replenish oxygen to the Valley of Mexico. The park area has been inhabited and held as special since the Pre-Columbian era, when it became a retreat for Aztec rulers. In the colonial period, Chapultepec Castle would be built here, eventually becoming the official residence of Mexican heads of state. It would remain such until 1940, when it was moved to another part of the park called Los Pinos. Today, the park is divided into three sections, with the first section being the oldest and most visited. This section contains most of the park's attractions including its zoo, the Museum of Anthropology, the Rufino Tamayo Museum, and more. It receives an estimated 15 million visitors per year. This prompted the need for major rehabilitation efforts which began in 2005 and ended in 2010.

Characteristics

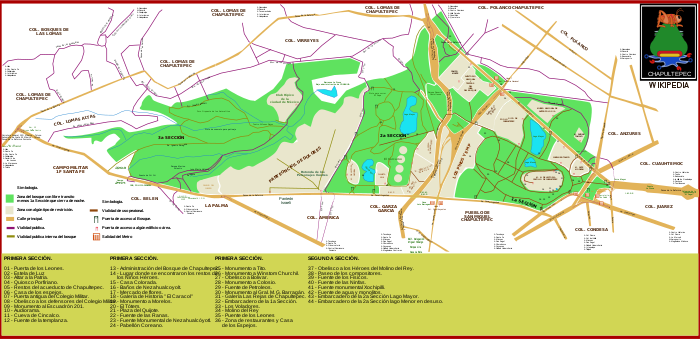

Chapultepec Park is the largest city park in Latin America, measuring in total just over 686 hectares.[1][2][3] It is classed as one of the world's great urban parks, along with Bois de Boulogne in Paris, the Imperial Gardens in Tokyo and Central Park in New York City.[4] The name "Chapultepec" means "at the grasshopper hill" in Nahuatl and refers to a large rock formation that is the center of the current park's "first section". Originally, this area was a forest outside of Tenochtitlan/Mexico City considered sacred in pre-Columbian times, but today it is entirely within the city (mostly in the borough of Miguel Hidalgo), surrounded by some of its primary business and commercial districts.[1][4][5] The park is divided into three sections, the first and oldest surrounded by fence and shut at night, and the other two left open. It contains nine museums, amusement parks, winding paths, commemorative sculptures, lakes and fountains.[1][4] Paseo de la Reforma passes most of the park and cuts through a portion on the north side.[4]

One of the park's main functions is to be an ecological space in the vast megalopolis. It is considered the first and most important of Mexico City's "lungs", with trees that replenished oxygen to the Valley of Mexico.[3][4][6] It is a large unpaved area that allows for aquifer recharge, ameliorates the "heat-island" effect, and attracts rain.[3] It is a refuge for migratory birds from Canada, the U.S. and other regions of Mexico, including the red-tailed falcon, the Harris falcon, wild ducks, geese, and others.[3] Anywhere from 38 to 60 species of birds can be found here including some native non migratory species such as the Yucatán canary and a type of heron called the "water dog".[3][4] There are also more than a dozen species of reptiles and amphibians[4] and a number of species of various types that are in danger of extinction including the axolotl, Goodeidae, alandrias, the carpenter bird and the white-tailed hummingbird.[3] The park is home to a large number of Montezuma cypress, locally called "ahuehuete" trees, with some hundreds of years old, many having been planted by the Aztecs. There are also 165 other species, mostly in the third section.[4] It is estimated by city authorities that 100 million pesos are needed annually to maintain the ecology of the park.[3]

For Mexico City residents, the park is valued as a cultural and historic area as well as green space.[4] The area has vestiges showing human presence as far back as the Toltecs with a number ruins from the pre-Columbian through to the colonial period.[3] Archeological studies have unearthed and identified tombs associated with Teotihuacan, a Toltec altar on the summit of Chapultepec Hill, remains of a colonial era aqueduct, paths associated with Nezahualcoyotl and an area where Aztec priests ingested peyote as part of religious rites.[3][4] One notable site is the Baths of Moctezuma, which was a systems of tanks, reservoirs, canals and waterfalls constructed by the Aztecs.[4] The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia has the park, as well as the Castle of Chapultepec on the hill listed as Mexican heritage sites, and has submitted the area for consideration as a World Heritage Site.[7][8]

The park received an estimated 15 million visitors each year, and daily visits have exceeded 250,000.[3][9] Sunday is the most popular day to visit as the museums are free, and many Mexican families will spend the entire day in one or more sections, walking, seeing the attractions and picnicking or grilling.[4] Despite its local popularity, however, foreign visitors usually only see the small fraction near the museums.[3][4] The park is easy to get to via public transportation. Metro Lines 1 and 7 have stations at park entrances to the east and south respectively. Several bus lines along Paseo de la Reforma.[4]

First section

The oldest and most visited portion of the park is called the "first section".[4] It is the most developed area with a wrought iron fence and gates that extend around its perimeter.[4][10] These fences mostly separate it from the streets that form its boundaries: Avenida Constituyentes, Paseo de la Reforma, Avenida Chivatito and the Anillo Periférico. The interior measures 274.03 hectares, with 182 of this undeveloped green space.[7] It contains most of the best known of the park's attractions such as the Lago Menor (Small Lake), the Nezahuacoyotl Fountain, the Fuente de las Ranas, the Quixote Fountain, the Templanza Fountain, the Altar a la Patria, the Niños Héroes Obelisk, the Monumento a las Águilas Caídas (Monument to Fallen Eagles), The Ahuehuete and the Baths of Moctezuma. The best known museums are here as well including Museo Nacional de Historia-Chapultepec Castle, the Casa del Lago (UNAM), the Auditorio Nacional, the Centro Cultural del Bosque, the Museo de Antropologia, the Rufino Tamayo Museum and the Museo de Arte Moderno (Modern Art Museum). It also contains the Zoo, the Jardin de Tercera Edad and the Audiorama.[7] These are connected by various paved paths, many of which have names such as the Avenue of the Poets, which is lined with bronze busts of famous literary figures.[11] It also has living trees which are hundreds of years old.[7]

This section of the park also contains the geological formation that gave the park/forest its name: Chapultepec Hill. It is a formation of volcanic rock and andesite, which is common in the Valley of Mexico and contains small caves and sand deposits.[8] "Chapultepec" in Nahuatl means "grasshopper hill" but it is not clear whether the "Chapul" (grasshopper) part refers to the shape of the hill, or the abundance of grasshoppers in the surrounding woods.[4] This hill was considered special during the pre-Hispanic period from the Toltecs in the 12th century to the Aztecs up to the time of the Conquest by the Spanish. Remains of a Toltec altar have been found at the top of the hill, a number of burials and its use was reserved only for Aztec emperors and other elite.[8][12] After the Conquest, a small chapel dedicated to the Archangel Michael was built on the hill by Claudio de Arciniega in the middle of the 16th century.[8] In the 18th century, the Spanish built the Chapultepec Castle, which initially was a summer retreat for viceroys.[4][12] After Independence, the Castle remained for the elite, becoming the official resident of the Mexico's heads of state, including the Emperor Maximilian, who had the Paseo de la Reforma built to connect this area with the historic center of the city. During this time, the Castle and the gardens around it were enlarged and embellished a number of times, giving the Castle a floorspace of 10,000m2. The most outstanding of the patios and garden is the Alcázar.[8][12] In 1940, the president's residence was moved to the nearby Los Pinos complex and the castle was converted into the Museum of History, under the auspices of the federal government, along with the rest of the hill.[4][8] The museum contains twelve rooms which are open to the public, many of which as they were when the Emperor Maximilian lived there. It also contains a collection of furniture from the colonial period to the 19th century, utensils, suits, coins, manuscripts, sculptures in clay ivory and silver and many other art works. A number of items belongs to figures such as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, José María Morelos y Pavón, Agustín de Iturbide, Benito Juárez, Emiliano Zapata and others.[10] In addition, there are murals by José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Juan O'Gorman.[8] At the foot of the hill, there is a large monument to the Niños Héroes also called the Altar a la Patria, who threw themselves to their death here rather than surrender to invading U.S. troops in 1847.[4] This monument consist of six marble columns surrounding a mausoleum with the remains of the six cadets, and a figure of a woman who represents Mexico.[13]

The Chapultepec Zoo is the most visited attraction of the park, especially on Sundays when many Mexico City families come; it is estimated that half of all park visitors come to the zoo.[14] The zoo was established by its Alfonso L. Herrera, a biologist, and opened in 1924.[5] Herrera's intention was to reestablish the zoo tradition of the old Aztecs emperors and improve upon it. He began with species native to Mexico and then added others from the rest of the world. He modeled the zoo after the "Giardino Zoológico e Museo de Zoología del Comune di Roma" in Rome, Italy. Between 1950 and 1960, the zoo expanded, adding new species. In 1975, the zoo obtained two pandas from China. Since then, eight panda cubs have been born at the zoo, making it the first institution outside of China to breed the species. From 1992 to 1994, the zoo was completely remodeled, categorizing exhibits by habitat rather than type of species. Some of the most important Mexican species at the facility include a rabbit native to only a few volcanoes in Mexico, zacatuche (or teporingo), the Mexican wolf, ocelot, jaguar and ajolote.[5][15] Today, it has 16,000 animals of 270 species, separated into four sections according to habitat: tropical forest, temperate forest, desert and grassland. About one third of the animals are native to Mexico.[14]

Most of the museums in the first section are located along Paseo de la Reforma.[14] Of all of the museums in the park, the most famous is the National Museum of Anthropology, considered to be one of the greatest archeological museums in the world. The museum has a number of antecedents beginning from the colonial period, but the current institution was created in the 1960s with the building and grounds designed by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. This museum has an area of 44,000m2 and 25 exhibit halls with sections devoted to each of the major pre-Hispanic civilizations in Mexico including the Aztec, Maya, Toltec and Olmec.[4][13] The permanent collection is so large, that it is possible to spend an entire day to see it. There are also temporary exhibits as well.[4] The Rufino Tamayo Museum is in the first section on Paseo de la Reforma. The permanent collection mostly focuses on the namesake, but there are also works by other Mexican and foreign artists that Tamayo donated.[4] During his lifetime, Tamayo collected one of the most important collections of 20th-century art, which includes names such as Andy Warhol, Picasso, Miró, Fernando Botero, Magritte, and about 100 others.[13]

The Museo de Arte Moderno (Museum of Modern Art) is located on Paseo de la Reforma and Calle Gandhi with various temporary exhibits.[4] It is house in a complex of modern architecture, which consists of two circular buildings surrounding a sculpture garden. It contains one of the best collections of modern art of the 20th century of Mexico. Artists include Dr. Atl, Frida Kahlo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Remedios Varo.[13]

The Casa de Cultura Quinta Colorada is located in the former accommodation for the forest rangers of the area in the early 20th century. The house is in European style and house various cultural activities as well as a small planetarium.[13]

At the foot of the Chapultepec Hill is an extension of the Museum of History called the Museo del Caracol. This museum narrates the history of Mexico in the winding form of a snail, the shape of the building from which its name comes.[13]

The Museo Casa Luis Barragan is the former home of architect Luis Barragán. The house has been preserved nearly intact as it was 1948, including the workshop. It also exhibits artworks from the 19th and 20th century.[13]

One of the most popular features in the first section is an artificial lake called the Lago Menor (Smaller Lake).[4][8] It is one of two lakes, with the larger Lago Major in the second section. However, this smaller lake is the better known and more popular, as paddleboats and small rowboats can be rented. The Lago Menor was created at the late 19th century, when the entire first section (then the entire park) was redesigned. At the same time, the Casa del Lago was constructed as well. It is shallow with an average depth of a little over one meter.[14] The Casa del Lago, also called the Restauranto del Lago is now a restaurant that serves continental food and some Mexican dishes.[4]

In addition to the lake there are a number of large fountains. The Quixote fountain is surrounded four benches covered in tile with images from Don Quixote. To the side of this plaza, there are two columns. On the right there is a figure of Quixote with the face of Salvador Dalí and on the other side, there is a depiction of Sancho Panza with the face of Diego Rivera. Both statues were made of bronze by José María Fernández Urbina.[10] The Fuente de las Ranas (Fountain of the Frogs) was created in the 1920s, by Miguel Alessio Robles in Seville, Spain.[10] The Nezahualcoyotl Fountain was inaugurated in 1956. It measures 1,250m2 and surrounds a statue of the Aztec ruler nine meters tall in black stone.[13]

Throughout the first section there are trees, the most famous of which are the Montezuma cypress, locally called "ahuehuetes". A number of these are hundreds of years old, although there are far fewer due to a past disease epidemic.[4][14] One dead specimen is called the Ahuehuete of Moctezuma, El Sargento (The Sargeant) or Centinela (Sentinel). The last two names were given by cadets of the country's military school, the Colegio Militar in the 19th century. The tree remains as a monument to the area's history, measuring fifteen meters high, forty in circumference and lived 500 years. Another tree of the species, still living, is El Tlatoani, which is about 700 years old and is the oldest resident of the park. In addition to these trees, there are sequoias, cedars, palms, poplars, pines, ginkgos and more.[14]

Los Pinos has been the official residence of the presidents of Mexico since 1941 and it is considered to be part of the park although there is no public access. The residence is a white stucco structure which can be seen from the nearby Periferico or from the Molino del Rey, a former millhouse and site of a battle of the Mexican–American War in 1847.[4] Los Pinos is on one edge of the park.[14]

The National Auditorium is one of Mexico City's principal arenas primarily hosting musical ensembles and dance troupes. Prominent singers from Mexico and elsewhere in Latin American perform here regularly, as well as occasional American artists.[4] The park hosts a number of cultural events during the year. The best known of this is the regular performance of Swan Lake, on a stage over park of the Lago Menor, using the Chapultepec Castle as a backdrop. This performance has been given since 1978 in warmer months.[4][13] Night tours of the first section in the train that circuits the park is popular around Christmas time, when many of the attractions are lit for the season. The Ballet Folklorico de Mexico also holds performances on occasion at the Chapultepec Castle.[10]

Second section

The second section of the park was created in 1964 taking over lands which used to be farm. Today, it is separated from the first section by the Anillo Periférico road and measures 160.02 hectares. It is not as developed as the first section but it is also dedicated to recreational activities. It also contains the Lago Mayor lake, which contains the Monumental Fountain, the largest in Latin America and is surrounded by several restaurants and cafes. Nearby are the Compositores, Xochipilli and Las Serpientes fountains.[4][16]

The area contains jogging trails, places for yoga and karate and other exercise facilities among the trees. It is estimated that 1,000 people each day come here to exercise.[4][17] The jogging trails were doubled from 2 km to 4 km in the late 2000s.[18]

One part of this section is dominated by the Feria de Chapultepec amusement park, located near the Lago Mayor, just off the Anillo Periférico. The park has a capacity of 15,000 people and is visited by about two million each year. It includes several roller coasters including the Montaña Infinitum, which contains three loops.[19]

This section contains museums such as El Papalote, the Museo Tecnológico de la CFE and the Museo de Historia Natural. El Papalote (means "the kite") is an interactive children's museum which invites children to touch and manipulate the exhibits, with tours guided by adolescents. The exhibits are divided thematically with names such as "Soy" (I am), "Comunico" (I communicate) and "Pertenezco" (I belong). There are temporary exhibits as well as an IMAX theater for special videos. The Museo Tecnológico de la CFE (CFE Technology Museum) consists of four very large halls which exhibits modern advances in technology. In its surrounding gardens, there are old locomotives, railcars and tracks. It also contains an auditorium for events and a planetarium. The Museo de Historia Natural (Museum of Natural History focuses mostly on the origins of life with its permanent exhibits. It also hosts temporary exhibits and academic conferences.[13]

The Cárcamo de Tlaloc or Cárcamo del Río Lerma was built between 1942 and 1952, to capture water sent to the Valley of Mexico from the Lerma River basin in the Toluca Valley. The major parts open to the public consist of a pavilion, covered with an orange half cupola and a fountain with an image of Tlaloc. Originally, the water was stored underground and pumped to the surface when needed. The main building has serpent heads on the four corners and there is a mural painted by Diego Rivera called "El Agua Origen de la Vida".[13][16]

In 2010, the second section of the park underwent rehabilitation, funded in part by a prívate charity called Probosque de Chapultepec. Most of the work was done on the jogging track, the Tlaloc Fountain, the Cárcamo de Dolores building, the mural "El Agua, Origen de la Vida" and the construction of an agora. These works together form the Museo Jardín del Agua (Water Garden Museum). In addition a large number of dead or diseased trees were removed and about 800 new ones planted.[18]

Third section

The third section of the park is located on the west side of the second and was inaugurated in 1974 with a surface area of 242.9 hectares. It is the least developed and the least known area, filled with trees, wildlife and silence.[2][4] Although some recreational activities such as archery and horseback riding are practiced here, the importance of this area is primarily as an ecological preserve for various species of flora and fauna, such as snakes and lizards.[2][3][4] In 1992, it was decreed as a Protected Natural Area.[2] In 2010, there were reports of feral dogs attacking visitors in the third section. There are an estimated 150 feral dogs living in the small canyon areas of this section.[20]

History

According to archeological studies, there has been human presence since at least the pre-Classic period with the first identified culture in evidence that of the Toltecs. It was they who gave the area the name of "grasshopper hill" which would become Chapultepec. Remains of a Toltec altar have been found on the hill's summit. In the Classic Period, the area was occupied by people of the Teotihuacan culture. When the Mexicas, or Aztecs arrived in the Valley of Mexico, it was inhabited by a people called the Tepanecas of Azcapotzalco.[1][4]

When the Aztecs took over the Valley of Mexico, they considered the Hill as both a sacred and strategic site. They began to use the area as a repository for the ashes of their rulers, and the area's springs became an important source of fresh water for the capital of Tenochtitlan.[1][4] Eventually, the area became a retreat strictly limited to the ruling and religious elite. In the 1420s, ruler Nezahualcoyotl was the first to build a palace in the area.[4][12] Moctezuma Xocoyotzin built reservoirs to raise exotic fish and to store water. He also had trees and plants from various parts of the Aztec Empire planted here. In 1465, Moctezuma Ilhuicanima ordered his portrait carved into a rock at the foot of the hill and constructed the Tlaxpana aqueduct, which measured three km.[1][10]

During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, one of the last battles between the Spanish and ruler Cuauhtémoc occurred at Chapultepec Hill in 1521.[1][4] Shortly thereafter, the Franciscans built a small hermitage over the indigenous altar on Chapultepec Hill.[12] Hernán Cortés appropriated Chapultepec and granted the northern portion to Captain Julian Jaramillo, who would become the husband of La Malinche. However, in 1530, Charles V decreed the area as the property of the City of Mexico and open to all.[1] The Spanish continued to use the Aztec aqueduct but in 1771, another one was deemed necessary for the growing Mexico City. The Chapultepec aqueduct lead from the springs of the forest to an area in what was the south of the city called Salto del Agua, flowing over 904 arches and 3,908 meters.[1] In 1785, the Franciscan hermitage was demolished to make way for the Chapultepec Castle, converting the hill and the forest around it into a summer retreat for colonial viceroys. The area was walled off from the general public and was the scene of elegant parties.[12][14]

After Mexico achieved Independence in 1821, the Castle became the official residence of the head of state. A number of these, especially Emperor Maximilian I and his wife, embellished and expanded the castle as well as the forest area around it.[12] The Hill was also the site of the Battle of Chapultepec in 1847, between Mexican and U.S. troops led by General Winfield Scott. A band of cadets were at the Castle when it was attacked and near the end of the battle, six of them decided to jump to their deaths from the castle on the hill to the rocks below. These six are referred to as the "Niños Héroes" and are honored by a monument near where their bodies fell. The castle remain the official residence of Mexican presidents until 1940, when this function as moved to the Los Pinos residence and the Castle was converted into a museum.[4]

Since then, the park was expanded twice, adding the second section in 1964[16] and the third section ten years later.[2] Since then, the focus has been on the maintenance of the area. By 1998, the paths of the park, especially in the first section, were saturated with over 3,000 peddlers with few regulations or norms.[21] In 2005, the first section of the park was closed for renovations, effectively evicting all vendors from it. When it reopened months later, permits for selling were strictly limited and continuing operations by police and other authorities are aimed at keeping vending in the park itself strictly limited. However, a number still manage to sell illegally, keeping watch for authorities and even communicating among themselves with radios.[22] At the entrances to the park, where the rules are not in places, vendors still crowd, partially blocking entrances and even covering signs to the most direct entrances so that visitors need to wade through labyrinths of vendors to find an entrance.[23]

Maintenance issues have closed parts of the park from time to time, such as in 1985, to exterminate rats and other pests.[4] However, by 2005, the park was filled with trees in poor condition, scum in the lakes and fountains and mountains of trash.[11] From that year until 2010, the park was closed section by section for restoration and rehabilitation projects. The first section was closed for eight months in 2005, for work that included dredging lakes, pruning and removing trees, picking up tons of debris and expelling hundreds of vendors.[11] Shortly thereafter, projects on the second and third sections of the park began, mostly to control or eliminate rats, feral dogs and cats, pigeons and other introduced species.[3] As of 2005, migratory birds began to make a comeback at the park with the eradication and relocation of introduced species such as geese and ducks which were aggressive to other species. The park hosts more than 100 species of this kind of bird, with some reproducing here for the first time in decades. Other native mammals have returned as well, including the tlacuache and the cacomistle.[24] In 2010, projects include renovating jogging tracks, and planting more than 800 trees including acacia café, pino azul, pino peñonero, holm oak, pino moctezuma, pino prieto and grevilia as well as the removal of dead or severely infected trees. These rehabilitation efforts of the 2000s, were funded by a combination of government and private funds, by groups such as Probosque.[6]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Historia del Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Dirección del Bosque de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "3ª Seccion del Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Dirección del Bosque de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Entrará el Bosque de Chapultepec en nueva etapa de rehabilitación". El Cronica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City. June 26, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Larry Rother (December 13, 1987). "Chapultepec Park: Mexico in Microcosm". New York Times. New York. p. A15.

- ^ a b c "Zoólogico de Chapultepec Alfonso Herrera" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Dirección del Bosque de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bertha Sola (July 29, 2010). "Termina saneamiento del Bosque de Chapultepec". La Cronica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "1ª Seccion del Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Dirección del Bosque de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Chapultepec". Antropología e Historia (in Spanish). Mexico: Artes e Historia México, INAH. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Darán nueva imagen al Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City. DDM. May 11, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Carlos Perez Gallardo (December 14, 2009). "Nocturno a Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico: INAH. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c Reed Johnson (June 15, 2005). "Residents Breathe Deep as Mexico City Park Reopens". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico: INDAABIN. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jimenez Gonzalez, Victor Manuel, ed. (2009). Ciudad de Mexico Guia para descubir los encantos de la Ciudad de Mexico (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editorial Oceano de Mexico SA de CV. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-607-400-061-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Chapultepec es el pulmón verde más importante, representa el 52% de áreas verdes de nuestra ciudad". Televisa (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 31, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historia". Zoologico de Chapultepec (in Spanish). Mexico City: Government of Mexico City. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "2ª Seccion del Bosque de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Dirección del Bosque de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Fernando Ríos (July 23, 2010). "El Bosque de Chapultepec no será privatizado". El Sol de Toluca (in Spanish). Toluca, Mexico. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Inician trabajos de restauración en segunda sección del Bosque de Chapultepec". Radio Formula (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 31, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "La Feria de Chapultepec" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Direccion de Chapultepec. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Mirna Servín Vega (March 4, 2010). "Brigada Animal vigilará Bosque de Chapultepec". Periódico La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Blanca Estela Botello (May 22, 1998). "Satura Chapultepec a avance de ambulentes". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Mariel Ibarra (July 22, 2007). "Vigilan acceso a bosque". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Mariel Ibarra (July 15, 2007). "Laberinto en el bosque". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ivan Sosa (June 9, 2005). "Recuperan fauna de Chapultepec". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)